*Note: If you find the text on some of the images blurry or hard to read, right-clicking the image and then selecting “open image in new tab” may improve the issue.

Policy Concerns

- Funding needs for mental health services post-COVID-19, to assist students dealing with trauma, anxiety, and stress related to the pandemic and its aftermath.

- Addressing the need for more recovery-oriented educational supports, such as schoolwide positive behavioral interventions and support, in addition to classroom-based social and emotional learning

- Addressing the disproportionate amount of exclusionary disciplinary measures for students receiving special education services and students of color.

- Addressing the disproportionate use of corporal punishment on students with disabilities or special needs.

- Lack of trauma-informed care training among teachers and other school personnel.

- As a result of the 86th legislative session, there is no longer a limit on the number of school marshals per student ratio.

- Monitoring threat assessment team outcomes, as other states have disproportionate assessments completed for students of color and students with disabilities.

- Ensuring appropriate resources and supports for teachers and staff to promote and support their mental health and well-being.

- Inadequate funding prioritized for mental health professionals in schools, leading to a severe gap in professional-to-student ratios across the state.

- Providing a definition of school social work services to the Texas Education Code.

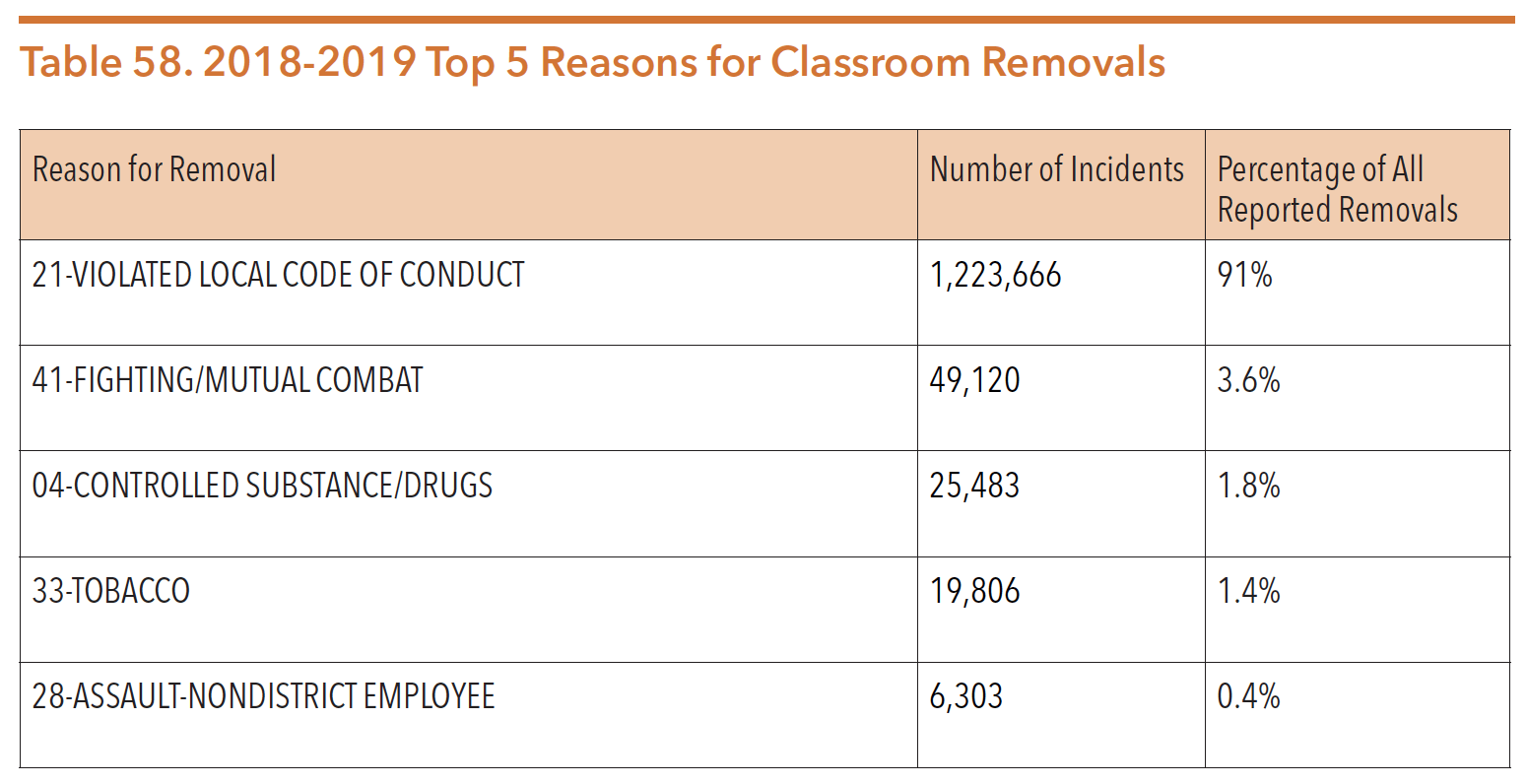

- Lack of transparency in statewide discipline data.

- Lack of knowledge surrounding students’ classroom removals due to the disproportionality of classroom removals coded as a violation of local code of conduct.

- School districts’ inability to enroll as a Medicaid provider to receive reimbursement for and provide mental health services to any student who is a Medicaid recipient. Currently, only schools enrolled in the School Health and Related Services (SHARS) program are able to bill Medicaid for certain services only for children receiving special education services.

- Ensuring provisions and policies related to school safety are not disproportionately impacting students with disabilities and students of color.

- Address current policies that allow foster care and youth experiencing homelessness who may be struggling with substance use to be removed from the classroom and given out of school suspension or an expulsion without other interventions or supports.

- Ensuring the revision of the health TEKS curriculum adequately educates students on mental health, substance use, suicide prevention, and overall well-being and wellness.

- Increasing state funding for Communities in Schools, which is yet to implemented across the entire state.

Fast Facts

- According to Texas Education Agency’s (TEA) Texas Academic Performance Report, 10.8 percent of school-aged children were enrolled in special education services in 2018-19.

- In 2017-18, the number of students experiencing homelessness rose substantially, as over 46,000 of the students identified as homeless were affected by hurricanes that year. In 2018-19, 1.3 percent of students were identified as homeless, the same percentage reported in 2016-17.

- The COVID-19 pandemic is expected to impact rates of evictions as families face prolonged unemployment and economic hardships, placing more families and children at risk of homelessness.

- Between 2008-09 and 2018-19, the percentage increase in the number of students identified as economically disadvantaged (22.5 percent) was greater than the percentage increase in the student population overall (14.4 percent).

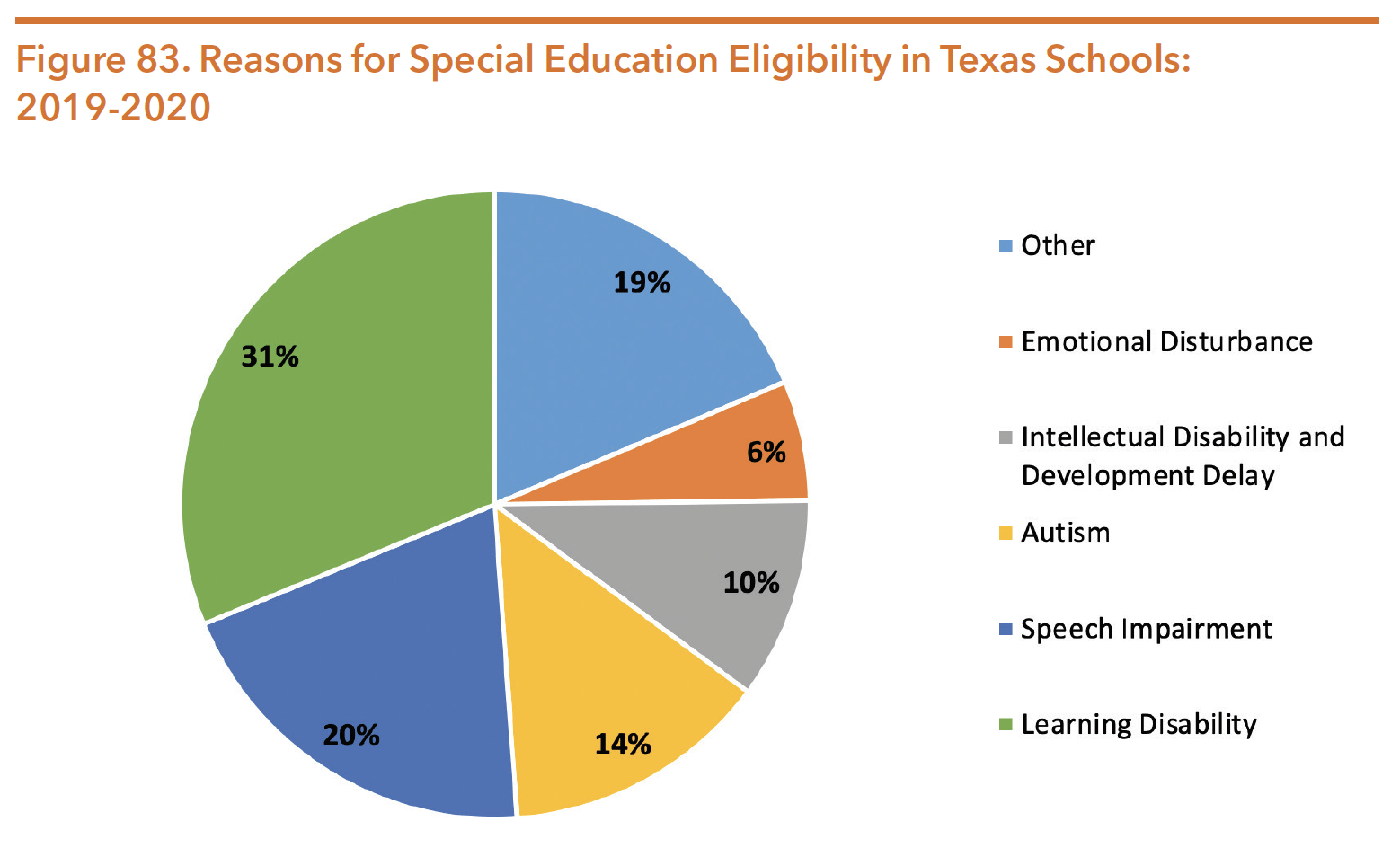

- Roughly 31 percent of students eligible for special education services in 2019-20 had a primary diagnosis of a learning disability, 14 percent had a primary diagnosis of autism, and 6 percent had a primary diagnosis of emotional disturbance.

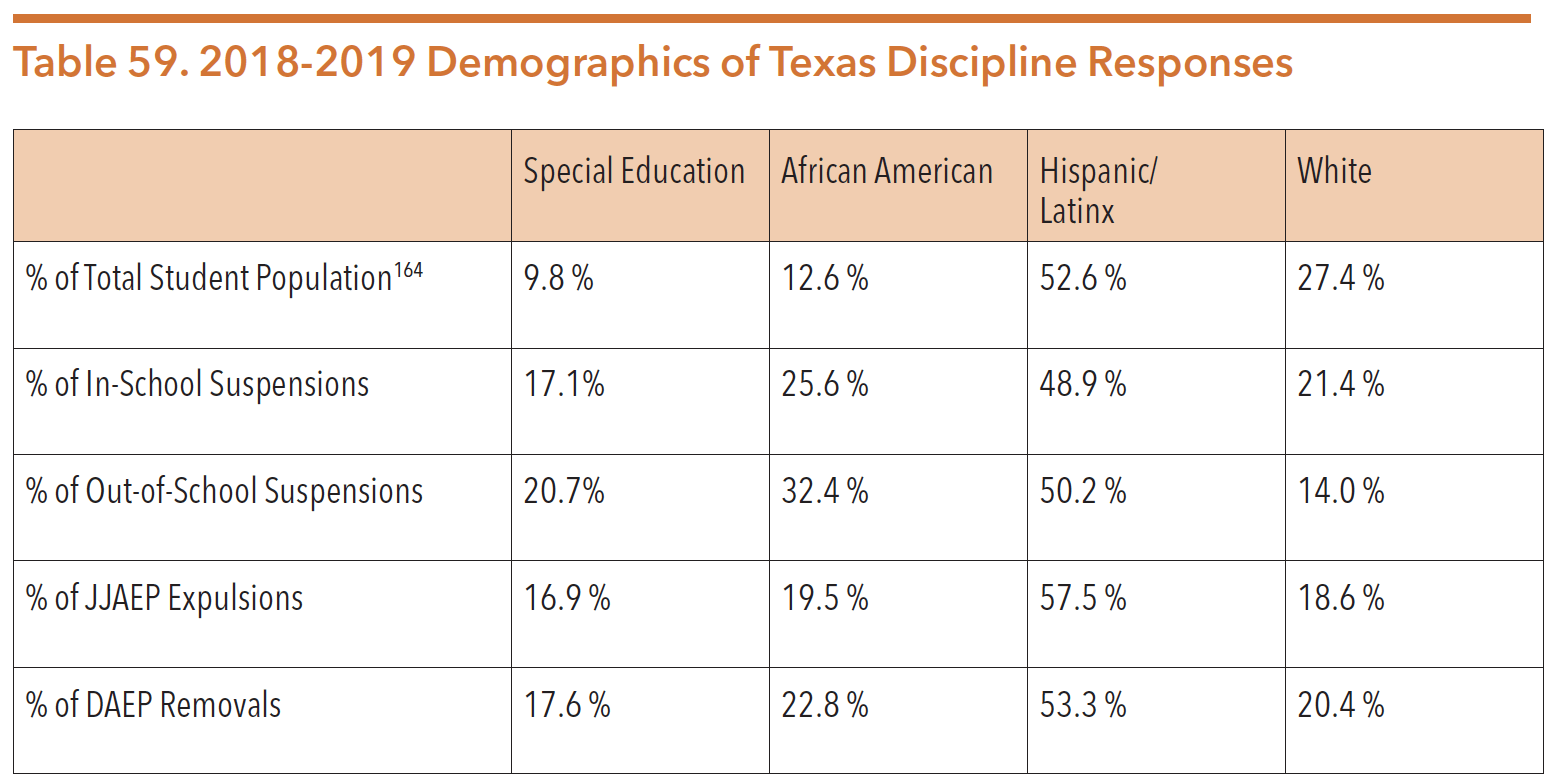

- In the 2018-19 school year, students enrolled in special education services represented 16.9 percent of expulsions to Juvenile Justice Alternative Education programs (JJAEPs), 17.6 percent of expulsions to Disciplinary Alternative Education programs (DAEPs) and 20.7 percent of out of school suspensions.

- The majority of expulsions to DAEPs and juvenile JJAEPs continued to be discretionary in 2018-19 (i.e., expulsions that were not mandated by state law but instead involve local codes of conduct).

- The majority of students in Texas identify as Hispanic (52.6 percent) and many of those students in Texas—nearly one million—are still learning English as their secondary language.

- During the 2017 academic year, more than half of school districts in the state did not require health education as part of requirements for graduation.

- One in five Texas high school students report using a prescription drug that was not prescribed to them.

- One in eight Texas high school students reported attempting suicide in 2018, almost twice the national average.

- Texas teens are more likely than the national average to have been offered, sold, or given illegal drugs at school in the last year

- During the 2016-2017 school year, Texas schools had a student-to-school social worker ratio of 7,548:1, well above the recommended ratio of 400:1.

- During the 2016-2017 school year, Texas schools had a student-to-Licensed Specialist in School Psychology (LSSP) ratio of 2,890:1, well above the recommended ratio of 1,000:1.

- During the 2016-2017 school year, Texas schools had a student-to-school counselor ratio of 442:1, well above the recommended ratio of 250:1.

TEA Acronyms

- AEP – Alternative education program

- AISD – Austin Independent School District

- ARD – Admission, review and dismissal

- ASCA – American School Counselor Association

- CCIT – Children’s crisis intervention training

- CEU – Continuing education unit

- CIS – Communities in schools

- CIT – Crisis intervention teams

- COVID- 19 – Coronavirus disease of 2019

- DAEP – Disciplinary alternative education program

- DFPS – Department of Family and Protective Services

- DSHS – Department of State Health Services

- ESC – Education service center

- FAPE – Free appropriate public education

- HHSC – Health and Human Services Commission

- IDD – Intellectual and other developmental disabilities

- IDEA – Individuals with Disabilities Education Act

- IEP – Individual education plan

- ISD – Independent school district

- ISS – In-school suspension

- JJAEP – Juvenile justice alternative education program

- LEA – Local education agency

- LMHA – Local mental health authority

- LSSP – Licensed specialist in school psychology

- MFA – Mental health first aid

- NCEC – Non-categorical early childhood

- NCTSN – National Child Traumatic Stress Network

- OSEP – Office of Special Education Programs

- OSS – Out-of-school suspension

- PBIS – Positive behavior interventions and services

- PPCD – Preschool program for children with disabilities

- PTSD – Post-traumatic stress disorder

- RSC – Regional service centers

- SEL – Social and emotional learning

- SHAC – School health advisory committee

- SHARS – School Health and Related Services Program

- SSA – Shared service agreement

- SRO – School resource officer

- TBSI – Texas Behavior Support Initiative

- TIC – Trauma-informed care

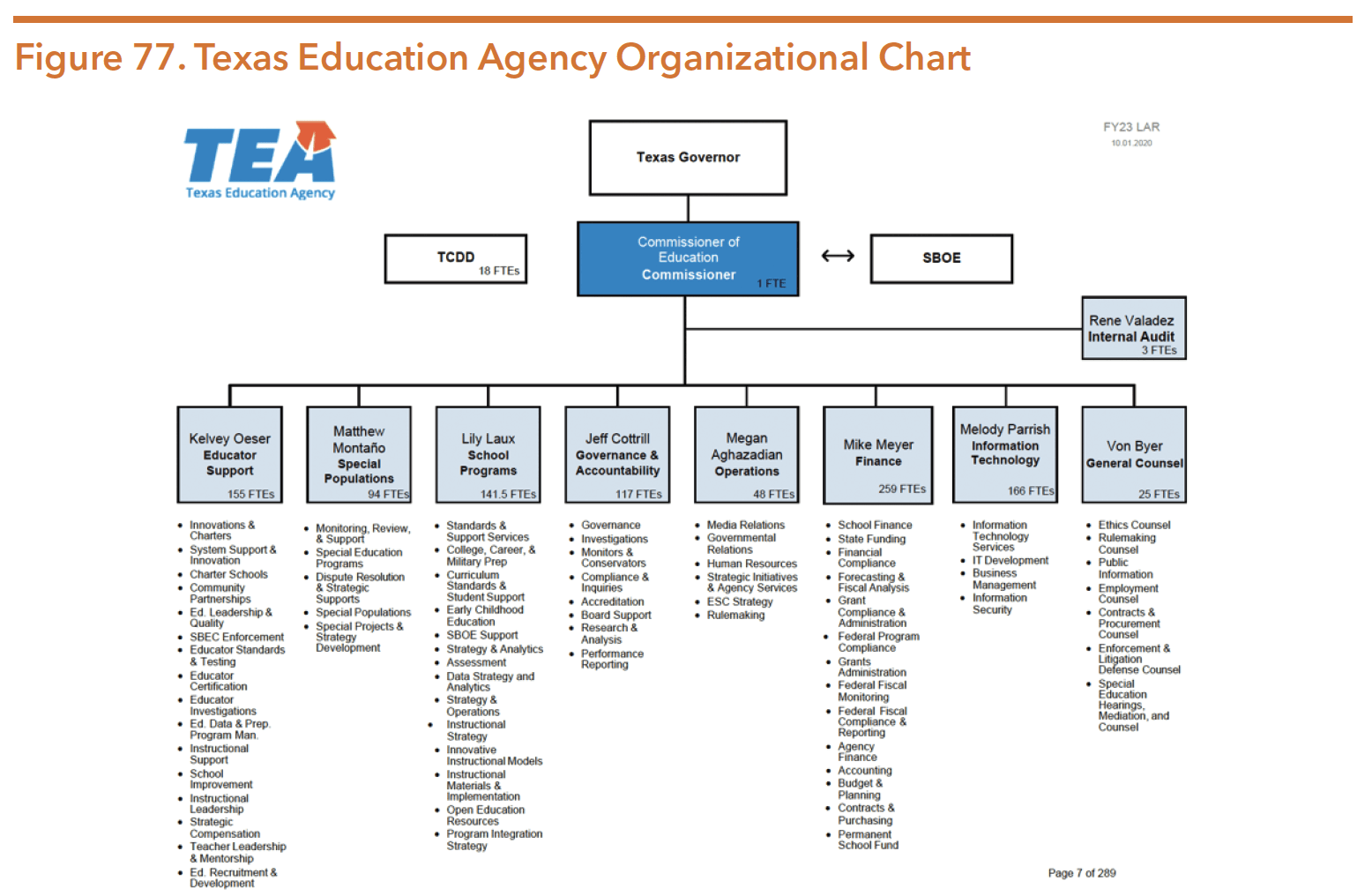

Organizational Chart

Source: Legislative Budget Board. (October 2020). Texas Education Agency, fiscal year 2022-2023 legislative appropriations request, October 2020 – volume 1 of 2.. Retrieved from http://docs.lbb.state.tx.us/display.aspx?DocType=LAR&agy=703&fy=2022

Overview

The Texas Education Agency (TEA) provides oversight and administrative functions for all primary and secondary public schools for the 1,201 school districts and 179 open-enrollment charter school campuses in the state of Texas.16 According to TEA, 5,431,910 students were enrolled in Texas public schools in the 2018-19 school year.17 Over a ten-year period, total enrollment in Texas schools increased by roughly 14.4 percent, or 682,339 students.

Unrecognized or poorly supported mental health conditions can negatively impact a child’s academic performance, classroom behavior, and school attendance. The most recently available data from the National Survey of Children’s Health (2018) reveals over 13 million children in Texas ages 3-17 years old had a mental, emotional, developmental, or behavioral need, however only 557,501 report receiving any support from a mental health professional.

In Texas, mental health supports and services may be provided in school settings by a number of trained professionals, including school counselors, nurses, school psychologists, and social workers. Despite the professional title, school counselors have many duties that are only tangentially related to mental health. Yet, according to Texas law, “the primary responsibility of a school counselor is to counsel students to fully develop each student’s academic, career, personal, and social abilities.” Although the American School Counselor Association recommends a ratio of 250 students per school counselor, the ratio in Texas is almost double that number: there were 442 students per counselor for the 2016-17 school year. However, there are additional, non-counselor personnel that can provide much needed support and services in schools. These mental health workers can play a crucial role in strengthening a positive school climate, and ensuring mental health concerns are addressed for both students and teachers. Mental health professionals can include licensed clinical social workers, licensed school psychologists, occupational therapists, and other mental health professionals such as art and music therapists. Texas also has a special credential for Licensed Specialists in School Psychology, yet only 3,522 LSSPs worked across all Texas public schools in 2019. Texas does not have an adequate mental health professional workforce within the school system for any of the aforementioned professionals.

Changing Environment

Funding and legislative initiatives reflected a major focus on how to best keep schools safe throughout the 86th session. For more detailed information on the legislation passed, the Hogg Foundation completed a policy brief detailing the legislative provisions focused on mental health, school safety, and school climate. The brief can be found at: https://hogg.utexas.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/FINAL_86th-Lege_Policy-Brief_School-Climate.pdf

House Bill 18 (Price/Watson)

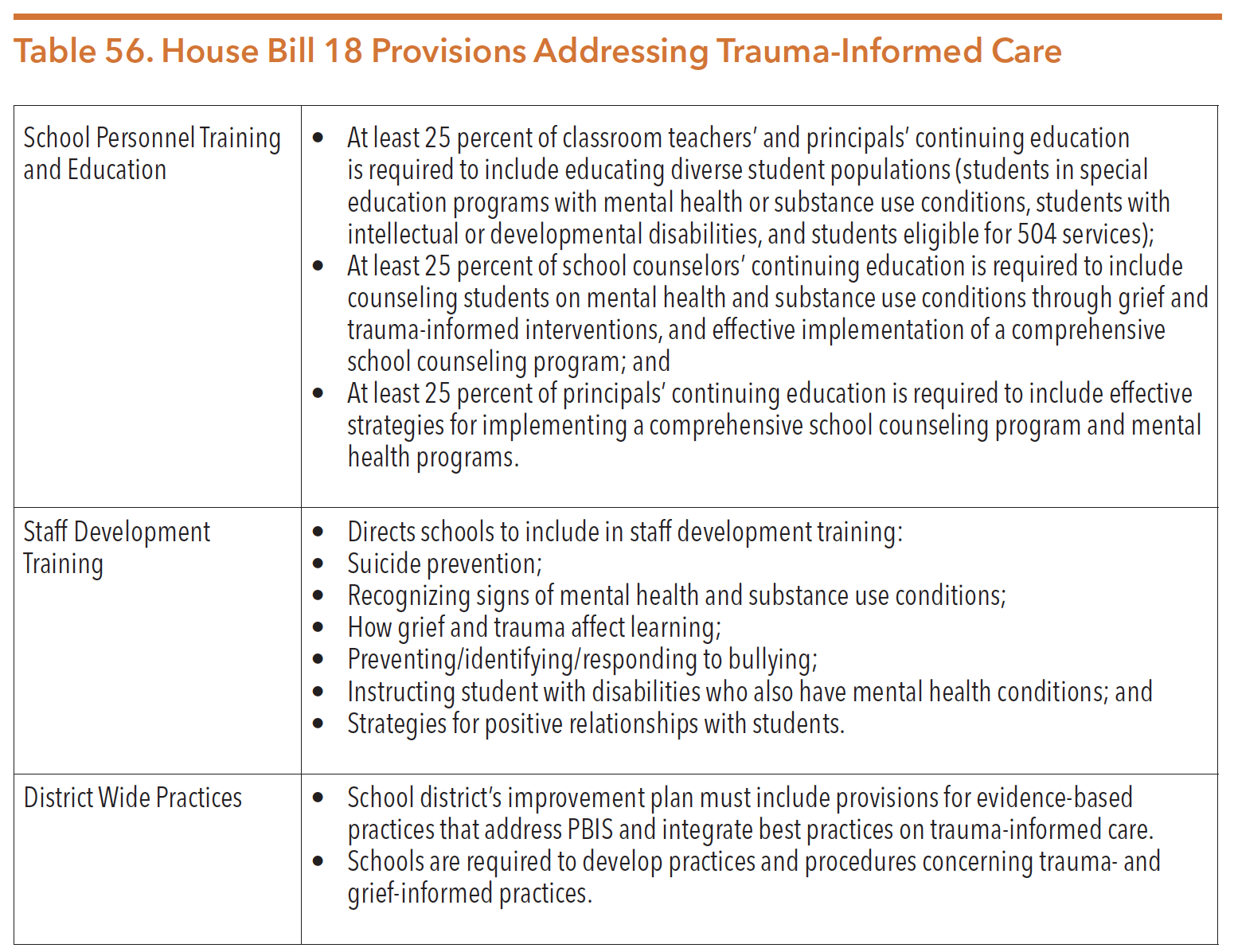

HB 18 is a comprehensive school mental health bill focused on providing resources, training, and education to students and school employees. This bill is aimed at improving the school climate, and adds mental health, trauma, and substance abuse education (inclusive of students with intellectual disabilities) to required staff development training for school counselors, teachers, and principals. HB 18 also adds mental health and more expansive substance use information to the health curriculum.

House Bill 19 (Price/Watson)

HB 19 requires each local mental health authority (LMHA) to employ a non-physician mental health professional to serve as a regional mental health and substance abuse resource to school districts located within the education service centers (ESC).

House Bill 65 (Johnson/West)

HB 65 requires school districts to include data on out-of-school suspensions in the reports they are mandated to submit to TEA.

House Bill 906 (Thompson/Powell)

HB 906 creates the Collaborative Task Force on Public School Mental Health Services to study and evaluate the impact of state-funded mental health services provided to students, their family/guardians, and school employees. The task force will also evaluate training provided to school employees.

House Bill 1387 (Hefner/Creighton)

HB 1387 removes the limitation of school marshal-to-student ratio.

House Bill 2184 (Allen/Huffman)

HB 2184 outlines requirements for school districts when a student transitions from an AEP, including a DAEP, JJAEP or other residential program or facility operated by TJJD or other governmental entity, to a traditional classroom. A personal transition plan must be included for the student.

Senate Bill 11 (Taylor/Bonnen)

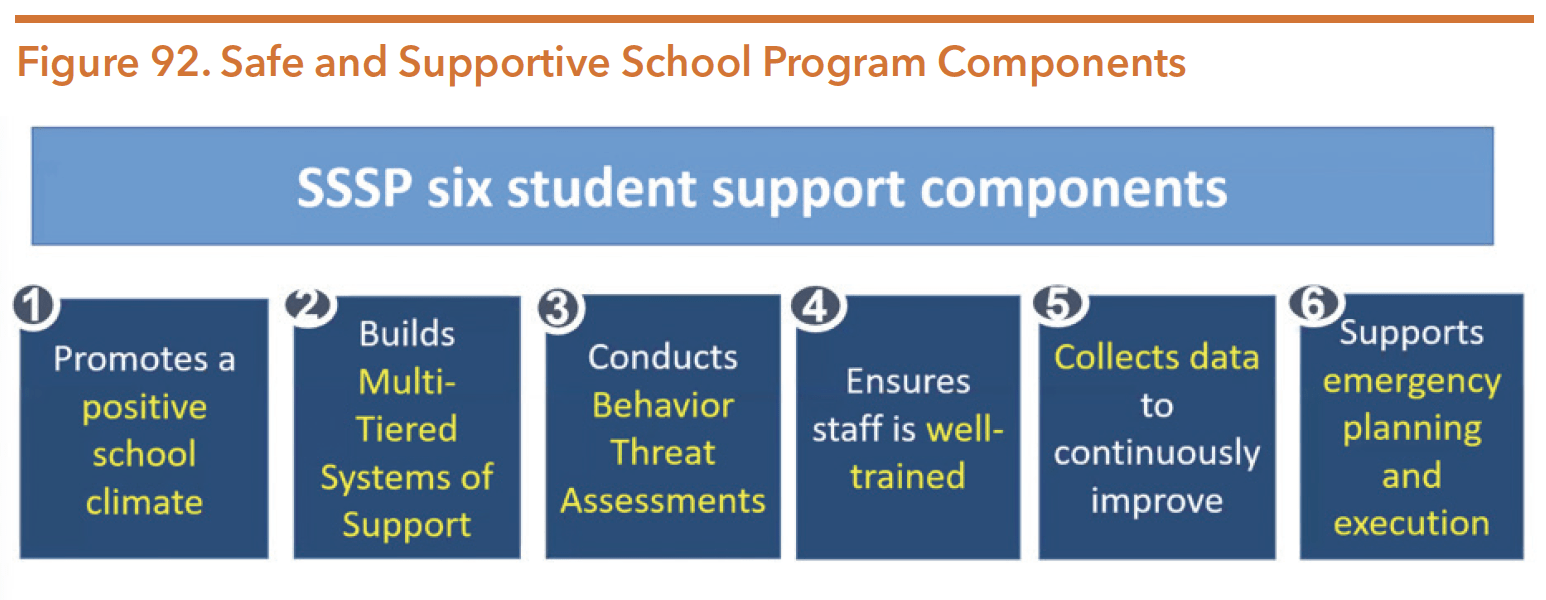

SB 11 is a comprehensive bill that focuses on expanding mental health initiatives, strengthens safety and emergency protocols, and provides funding to districts to increase safety and security on campuses. SB 11 addresses a multitude of areas related to school safety and mental health including physical hardening and building standards, as well as mental health and other supportive initiatives. These include the creation of Safe and Supportive School Program and Teams, and the creation of the Texas Child Mental Health Care Consortium and other telehealth and telemedicine programs after Senate Bill 10 (Nelson) was amended onto SB 11 during the legislative process.

Senate Bill 2432 (Taylor/Sanford)

SB 2432 expands mandatory student removal to DAEPS to include harassment as defined by the Penal Code.

House Bill 3 (Huberty/Taylor) – School Funding

HB 3 is a comprehensive education bill that has many provisions and changes to the school finance system. The bill includes $11.6 billion measure to which $6.5 billion is dedicated to public education spending, and $5.1 billion is dedicated to lowering property taxes. TEA provided multiple resources to help understand the bill in its entirety that can be found at https://tea.texas.gov/about-tea/government-relations-and-legal/government-relations/house-bill-3.

A few highlights of the bill include:

- Requires full-day Pre-K

- Funds an optional 30-day, half-day summer program

- Increases resources for students living in low-income families and for whom English is a second language

- Increases funding for special education

- Basic Allotment (BA) increase

- Tied to the Minimum Salary Schedule (MSS)

- 30 percent of increase must go to salary increase:

- 75 percent of the 30 percent must go to classroom teachers (more for 5+ yrs experience), librarians, school counselors, and school nurses;

- 25 percent may be used to provide an increase for full-time employees (except administrators) as determined by school district;

- Districts will have to report to legislature on each salary increase by position and amount; and

- Cannot use new hires towards 30 percent requirement, funding is for pay increases for current full-time employees.

- 30 percent of increase must go to salary increase:

- Tied to the Minimum Salary Schedule (MSS)

COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic presented new and unexpected challenges for communities, and greatly impacted schools. TEA recognizes that “as a result of school closures and remote learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic, students have been at higher risk of exposure due to adverse childhood experiences and first hand exposure to the effects of pandemic.” These incredible challenges will continue and evolve throughout the current school year and likely beyond. In response to the pandemic, TEA worked on a number of activities focused on supporting the mental health and well-being of students, their families, teachers, and the overall school. Some of these activities include:

- TEA posted information on their COVID-19 web page on remote counseling, a statewide mental health resource list, Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS) interventions, and how to contact hard-to-reach students. This website can be found at https://tea.texas.gov/texas-schools/health-safety-discipline/covid/coronavirus-covid-19-support-and-guidance

- TEA created a series of six trauma-informed care videos for educators during school reopening. These videos can be found at https://www.texasprojectrestore.org/

- TEA issued a To the Administrator Addressed letter with updates on the Safe and Supportive School Program (SSSP) required by Texas Education Code Sec. 37.115 as amended by SB 11. As of October 2020, TEA was working on the rulemaking process on SSSP and trauma-informed care, with guidance expected by summer 2021.

- In July 2020, TEA staff conducted virtual “listening tours” with school districts and Education Service Centers (ESCs) with expertise in providing student support services and well-being supports in a MTSS, including Project Advancing Wellness and Resiliency in Education (AWARE) Texas. TEA reports that their staff will use this input to develop guidance for providing supports for students and school staff in the recovery from COVID-19.

- In July 2020, the Project AWARE interagency partners hosted virtual office hours twice a month for the ESCs to support the well-being of students and school staff in their regions during COVID-19. Many ESCs have likewise initiated Professional Learning Communities with school counselors and district leaders to share resources from the Texas Education Code Sec. 38.253 inventories, MTSS school mental health lessons provided by Project AWARE, and new resources to support staff and student well-being as additional resources are identified.

- TEA collaborated with ESCs to establish voluntary School Mental Health Teams at each ESC.

- In July 2020, TEA coordinated with a therapist who volunteered to provide Trauma Informed Care: Circle of Support for Schools virtual sessions that were attended by over 500 district and ESC staff. TEA reports they will continue their efforts to bring virtual training and technical assistance consultation to districts.

CORONAVIRUS AID, RELIEF, AND ECONOMIC SECURITY (CARES) ACT

According to the Office of Elementary & Seconday Education within the U.S. Department of Education, Congress set aside approximately $13.2 billion through the CARES Act for the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER Fund). The funds are “emergency relief funds to address the impact that COVID-19 has had, and continues to have, on elementary and secondary schools across the Nation.” TEA calculated the entitlements following the statutory formula and guidance provided by USDE. The formula states that a local education agency (LEA) will receive the same proportionate share of the total ESSER formula grant as it received in proportion to the state’s Title I, Part A grant in 2019-2020. According to TEA, a minimum of 90 percent of the ESSER grant to TEA will be allocated to LEAs that received Title I, Part A funding in school year 2019-2020. Providing mental health support and services are allowable use of these funds. All allowable uses of the grant funding include:

1. LEA discretion for any purpose under:

- Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA)

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

- Adult Education and Family Literacy Act (AEFLA)

- Perkins Career and Technical Education Act

- McKinney-Vento Homeless Education Act

2. Activities related to coordination of preparedness and response to improve coordinated responses among LEAs with state and local health departments and other relevant agencies to prevent, prepare for, and respond to coronavirus;

3. Provide principals and others school leaders with the resources necessary to address the needs of their individual schools;

4. Address the unique needs of low-income children or students, children with disabilities, English learners, racial and ethnic minorities, students experiencing homelessness, and students in foster care, including how outreach and service delivery will meet the needs of each population;

5. Developing and implementing procedures and systems to improve the preparedness and response efforts of LEAs;

6. Training and professional development of LEA staff on sanitation and minimizing the spread of infectious diseases;

7. Purchasing supplies to sanitize and clean facilities operated by the LEA;

8. Planning for and coordinating during long term closures, including for how to provide meals to eligible students, how to provide technology for on line learning to all students, how to provide guidance for carrying out requirements under IDEA, and how to ensure other educational service can continue to be provided consistent with all federal, state, and local requirements;

9. Purchasing educational technology (including hardware, software, and connectivity) for students who are served by the local educational agency that aids in regular and substantive educational interaction between students and their classroom instructors, including low-income students and students with disabilities, which may include assistive technology or adaptive equipment;

10. Providing mental health services and supports;

11. Planning and implementing activities related to summer learning and supplemental afterschool programs, including providing classroom instruction or online learning during the summer months and addressing the needs of low-income students, students with disabilities, English learners, migrant students, students experiencing homelessness, and children in foster care; and

12. Other activities that are necessary to maintain the operation of and continuity of services in LEAs and continuing to employ existing staff.

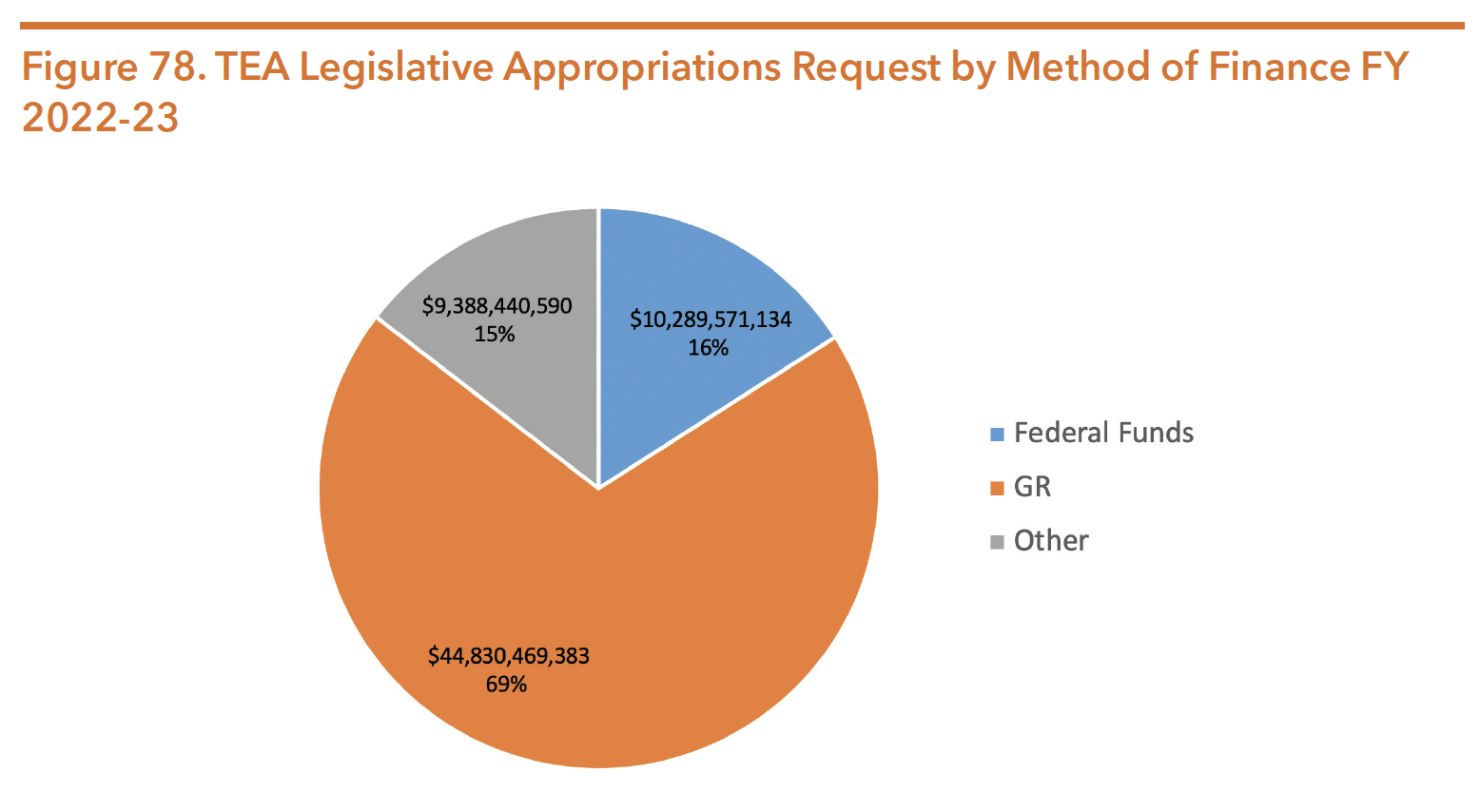

Funding

Source: Legislative Budget Board. (October 2020). Texas Education Agency, fiscal year 2022-2023 legislative appropriations request, October 2020 – volume 1 of 2. Retrieved from http://docs.lbb.state.tx.us/display.aspx?DocType=LAR&agy=703&fy=2022

The total requested TEA budget for FY 2022-23 is $64,508,481,207. If included in the budget, the Exceptional Items Requests would add an additional $25,711,500.

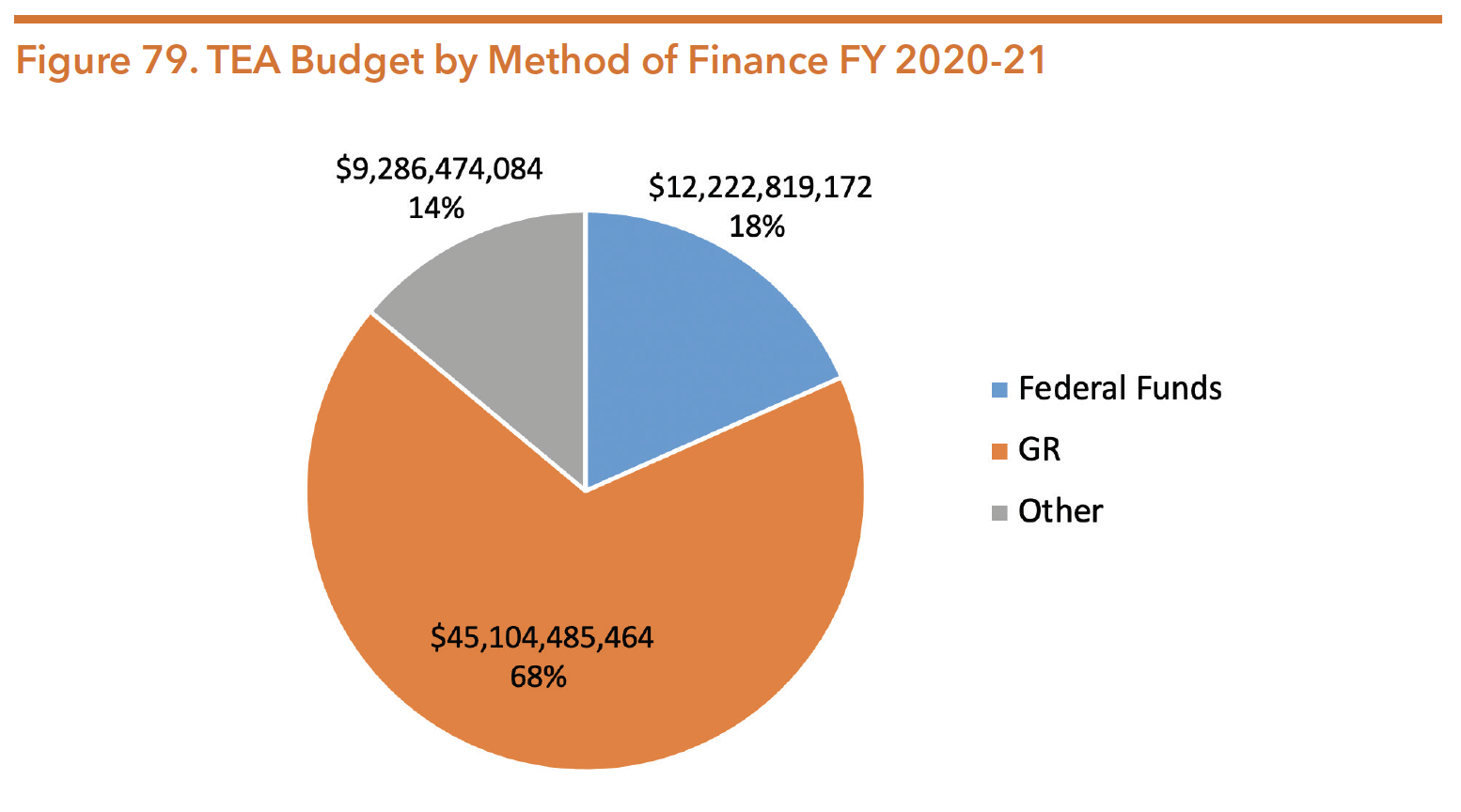

Source: Legislative Budget Board. (October 2020). Texas Education Agency, fiscal year 2022-2023 legislative appropriations request, October 2020 – volume 1 of 2. Retrieved from http://docs.lbb.state.tx.us/display.aspx?DocType=LAR&agy=703&fy=2022

The total TEA budget for FY 2020-21 was $55,838,888,685.

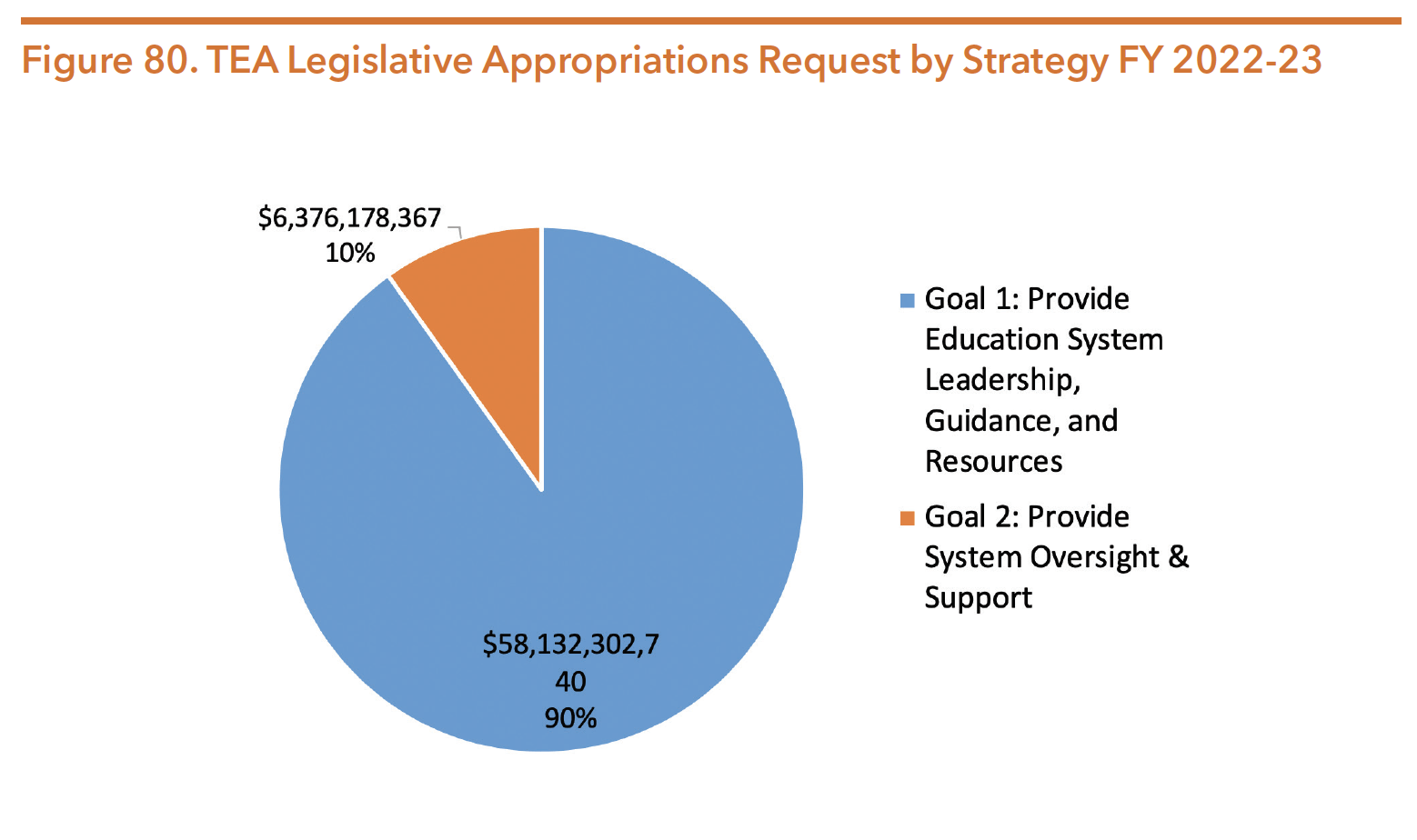

Source: Legislative Budget Board. (October 2020). Texas Education Agency, fiscal year 2022-2023 legislative appropriations request, October 2020 – volume 1 of 2. Retrieved from http://docs.lbb.state.tx.us/display.aspx?DocType=LAR&agy=703&fy=2022

INDIVIDUALS WITH DISABILITIES EDUCATION ACT

Under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), children and adolescents between the ages of 3 and 21 who have disabilities are entitled to receive a free and appropriate public education.30 IDEA first passed in 1975 (as the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, PL 94-142) and has been reauthorized multiple times. In its current form, the IDEA both authorizes federal funding for special education and related services andsets out principles under which special education and related services are to be provided for states that accept the funds.

IDEA consists of four parts:

1. Part A contains the general provisions, including the purposes of the act and definitions.

2. Part B contains provisions relating to the education of school-aged children (the grants-to-states program) and the state grants program for preschool children with disabilities (Section 619).

3. Part C authorizes state grants for programs serving infants and toddlers with disabilities.

4. Part D contains the requirements for various national activities designed to improve the education of children with disabilities.

Part B is the largest part of the IDEA (nearly 95 percent of the Acts’ total funding in FY 19). IDEA Part B authorizes the state grant program and stipulates the conditions for receiving funds. States are required to educate students with disabilities in the least restrictive environment, which means with their peers in a normal classroom, to the extent possible. States are also required to provide a free, appropriate public education to all disabled students, which:

- Is provided at public expense, under public supervision and direction, and without charge;

- Meets the standards of the state education agency;

- Includes an appropriate preschool, elementary school, or secondary school in the state; and

- Is provided in conformity with the Individual Education Program established for the child.

The amount required to provide the maximum amount for each state’s grant is commonly referred to as “full funding” of the IDEA. When IDEA was created, Congress’ intention was that (1) states would provide every eligible child a free appropriate public education (FAPE) in the least restrictive environment, and (2) states would not take on an untenable financial burden by agreeing to provide special education and related services. At that time, the expected cost of educating students with special needs was projected to be twice as much as the national average of educating students who do not require special education services. To support schools with increased costs, the federal government committed to contributing up to 40 percent of this anticipated additional cost. Despite this commitment, the federal government has given less than half of its committed financial support since IDEA’s first year of funding in 1981.

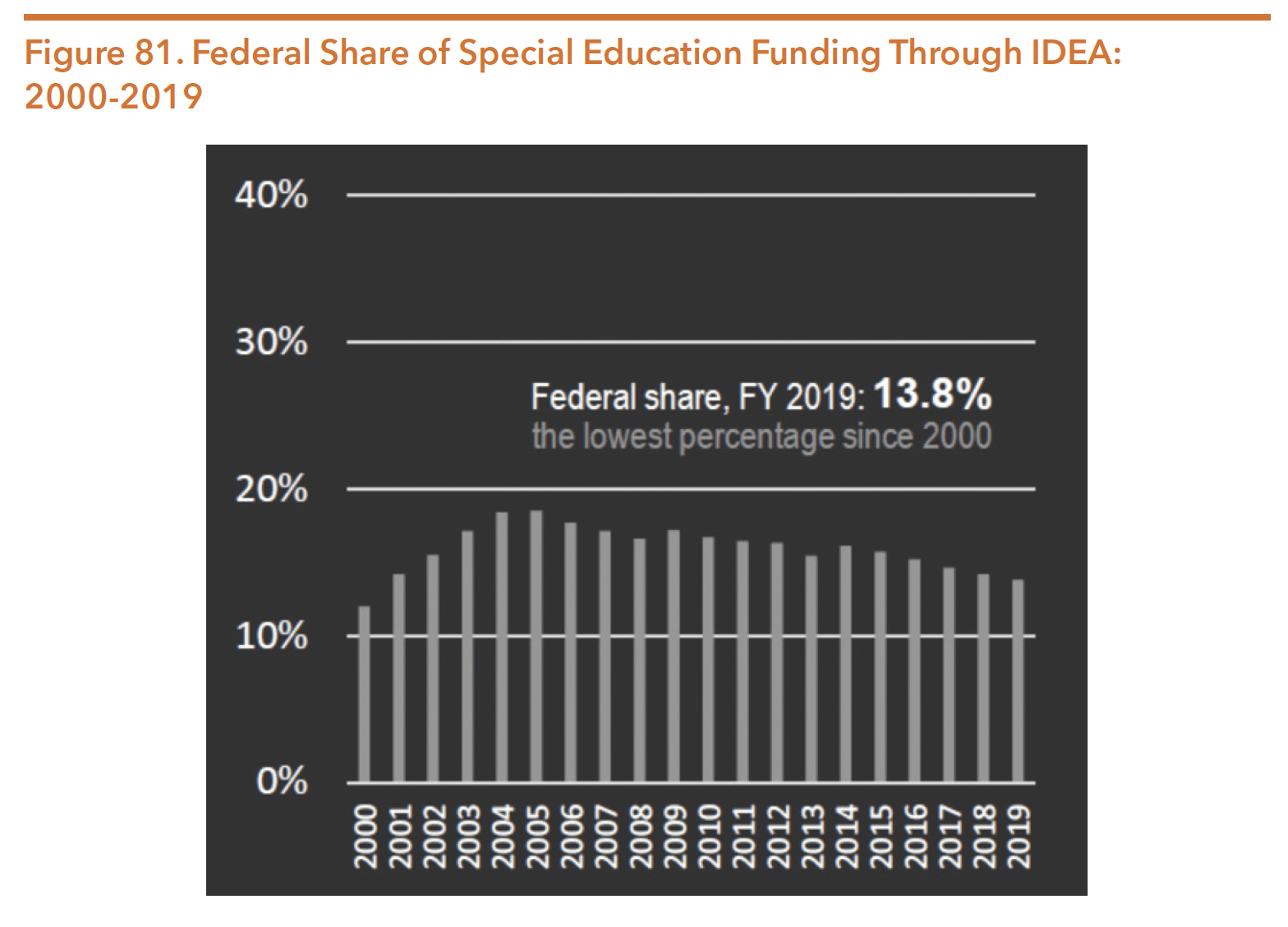

Overall, spending for special education programs has increased since the inception of IDEA and its predecessor, but federal and state funding for special education has not increased proportionately. Local funding must make up the difference in funding for this increased need in order to meet IDEA’s requirements for providing special education services in schools. As Figure 81 shows, federal funding for special education through IDEA has remained relatively constant for the past 14 years and it is expected to remain constant despite an increase in the number of students eligible to receive special education. The federal trend of under-funding special education resulted in IDEA falling more than $10 billion short of being fully funded in FY 2014. The federal FY 2020 budget provides $13.8 billion in funding for IDEA, up from $13.47 billion in FY 2019.

Excluding funding for preschools through IDEA, TEA received $1,975,477,627 in federal IDEA Part B funding for the 2020-21 biennium, resulting in a decrease of approximately three percent from the 2018-19 biennium ($2,030,489,139).41 For the 2022-23 biennium, the funding is expected to remain mostly unchanged at $1,982,750,442.

Source: The Advocacy Institute. (December 17, 2019). IDEA Money Watch. Retrieved from http://ideamoneywatch.com/balancesheet/?p=851

MEDICAID

In addition to funding from the federal and state government through IDEA, schools can bill Medicaid directly for certain eligible services through the School Health and Related Services (SHARS) program. Services provided by SHARS are made available through the coordination of TEA and HHSC. SHARS is a Medicaid financing program that allows local school districts and shared services arrangements to obtain Medicaid reimbursement for certain health-related services provided to students in special education. The state match requirement for SHARS Medicaid funding is met by using state and local special education allocations that already exist. School districts and shared service agreements (SSAs) must enroll as Medicaid providers and employ or contract with qualified professionals to provide these services.

Services covered by SHARS include:

- Audiology services

- Counseling

- Nursing services

- Occupational therapy

- Personal care services

- Physical therapy

- Physician services

- Psychological services, including assessments

- Speech therapy

- Transportation in a school setting

In order to receive SHARS services, students must meet all of the following requirements:

- Be 20 years of age or younger;

- Have a disability or chronic medical condition;

- Be eligible for Medicaid;

- Be enrolled in a public school’s special education program;

- Meet eligibility requirements for special education described in IDEA; and

- Have an individualized education program that identifies the needed services.

Delivery of Mental Health Services in Schools

For some youth, schools often serve as the first point of intervention when services or supports are needed because the majority of a young person’s day is in an academic setting. For some students, it can be as simple as having someone to talk to. For students with more complex needs, child and adolescent disorders will often continue into adulthood without early intervention.48 Many children in our public schools, while not living with serious emotional disturbance or mental illness, may be experiencing trauma or struggling with their mental health and well-being. Last year, 37 percent of Texas high school students reported feeling sad or hopeless for a period of two weeks or longer that resulted in decreased usual activity.

When needed, students are 21 times more likely to visit a school-based mental health service than a community mental health center. According to the American Counseling Association, in order to adequately support kids and their mental well-being in schools, Texas would need to double the number of counselors, triple the number of licensed specialists in school psychology (LSSP), and increase social workers 19 times to reach national levels. The Texas Education Code does not currently define school social work services, one crucial first step to getting more social workers in school systems. There are benefits for increasing mental health professional ratios in schools. For the schools that did follow the recommended ratio for counselors of 250:1, there were lower disciplinary rates and absenteeism, and increased graduation rates.

Early intervention with mental health concerns supports academic achievement, increases healthy stress management skills, improves social and emotional functioning and peer interactions, and allows schools to intervene before there is significant psychological deterioration. Furthermore, young children who receive effective, age-appropriate mental health services are more likely to complete high school, have fewer contacts with law enforcement, and improve their ability to live independently and be productive.

School-based mental health services encompass a wide variety of different programs and approaches. Special attention must be paid to schools in rural areas of the sate. A Texas A&M University-Kingsville study on access to mental health services found that rural schools struggle to provide mental health services to students; nearly half of the counselors surveyed in the study said that less than 25 percent of their students received adequate counseling services. According to a separate Center for Disease Control report, the percentage of children with diagnosed mental health and developmental disorders is consistently higher in rural areas. In Texas, the suicide rate is roughly 15 percent higher in rural counties (less than 20,000 residents) than in metropolitan ones. Barriers to delivering mental health services lead to inconsistent mental health care from school to school but even though access to services and supports varies based on a school’s region (i.e., urban vs. rural), academic level, and student population, most schools offer some level of mental health screening, referral or services.

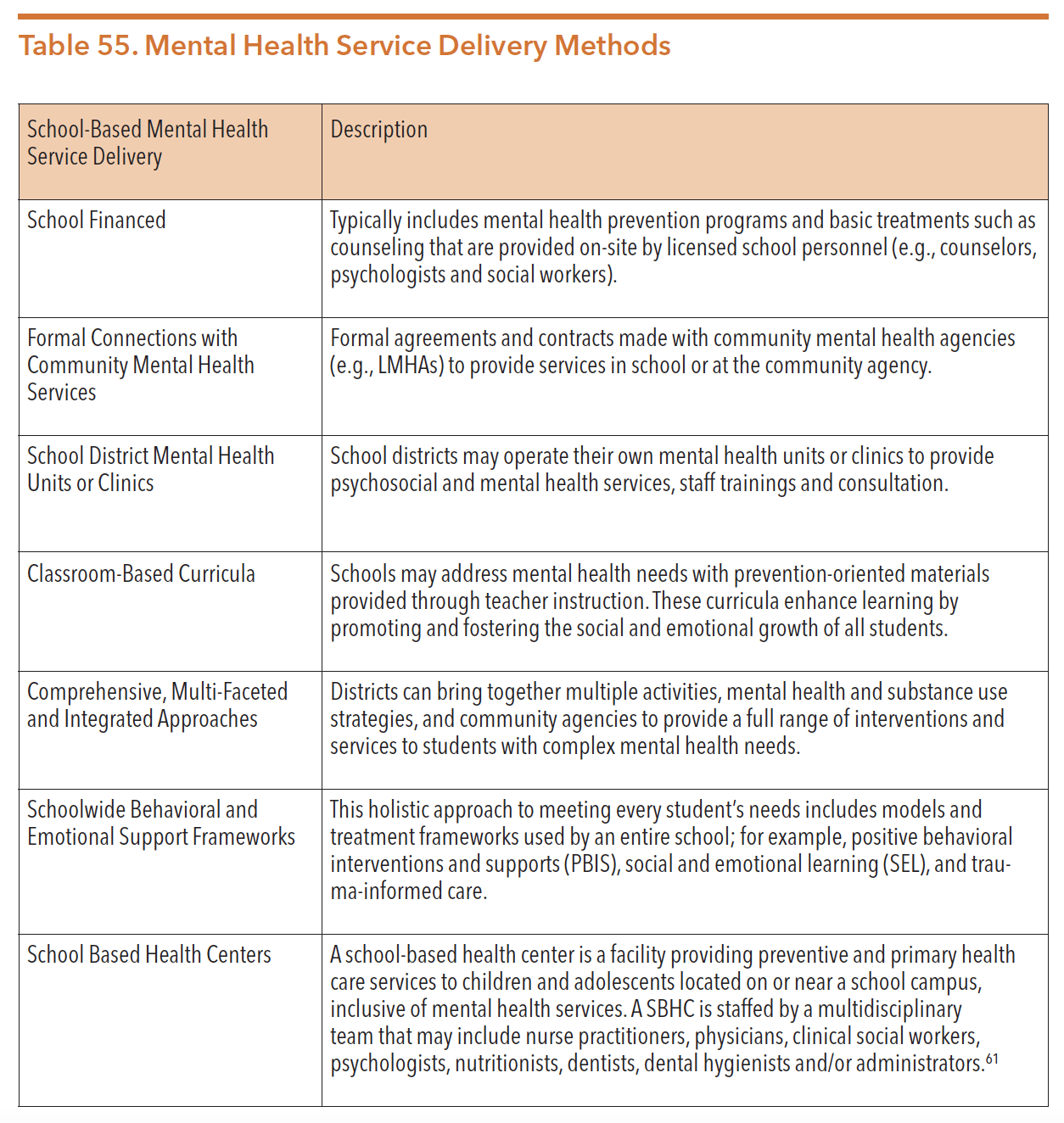

The different methods of delivering mental health services in schools are described in Table 55.

THE TEXAS CHILD HEALTH ACCESS THROUGH TELEHEALTH (TCHATT)

The Texas Child Health Access through Telehealth (TCHATT) Program is one component of the Texas Child Mental Health Care Consortium, established through SB 11 in the 86th Legislative Session. The Consortium is made up of 13 health-related institutions (HRI) of higher education. The legislation calls on the Consortium to “establish or expand telemedicine or telehealth programs for identifying and assessing behavioral health needs and providing access to mental health care services.” The TCHATT program will create or tap into existing telemedicine or telehealth programs to assist school districts with identifying student mental health care needs and accessing services, consisting of:

- Provision of direct psychiatry through telemedicine or counseling services through telehealth to children and adolescent within schools.

- Educational and training materials for school staff to assist in assessing, supporting, and referring children and adolescents with mental health needs for appropriate treatment and supports.

- Analysis and mapping of existing telemedicine and telehealth programs that are currently providing, or can be adapted to provide, services to schools.

- Statewide data management system that will track calls and responses in order to measure both need and responsiveness.

Each HRI may provide TCHATT services differently, but each will collaborate with schools to establish a process for referral. TCHATT services can last up to four sessions and can include assessment, therapy, psychiatric care, and referral assistance. Families will not be charged for services. As of September 2020, measures of the students seen in TCHATT, the types of services and referrals provided to students, and the outcomes of these services are being standardized. Additionally, the work of the Texas Child Mental Health Care Consortium considered the impact of COVID-19 and began adjusting the process for telehealth at families’ homes in addition to schools.

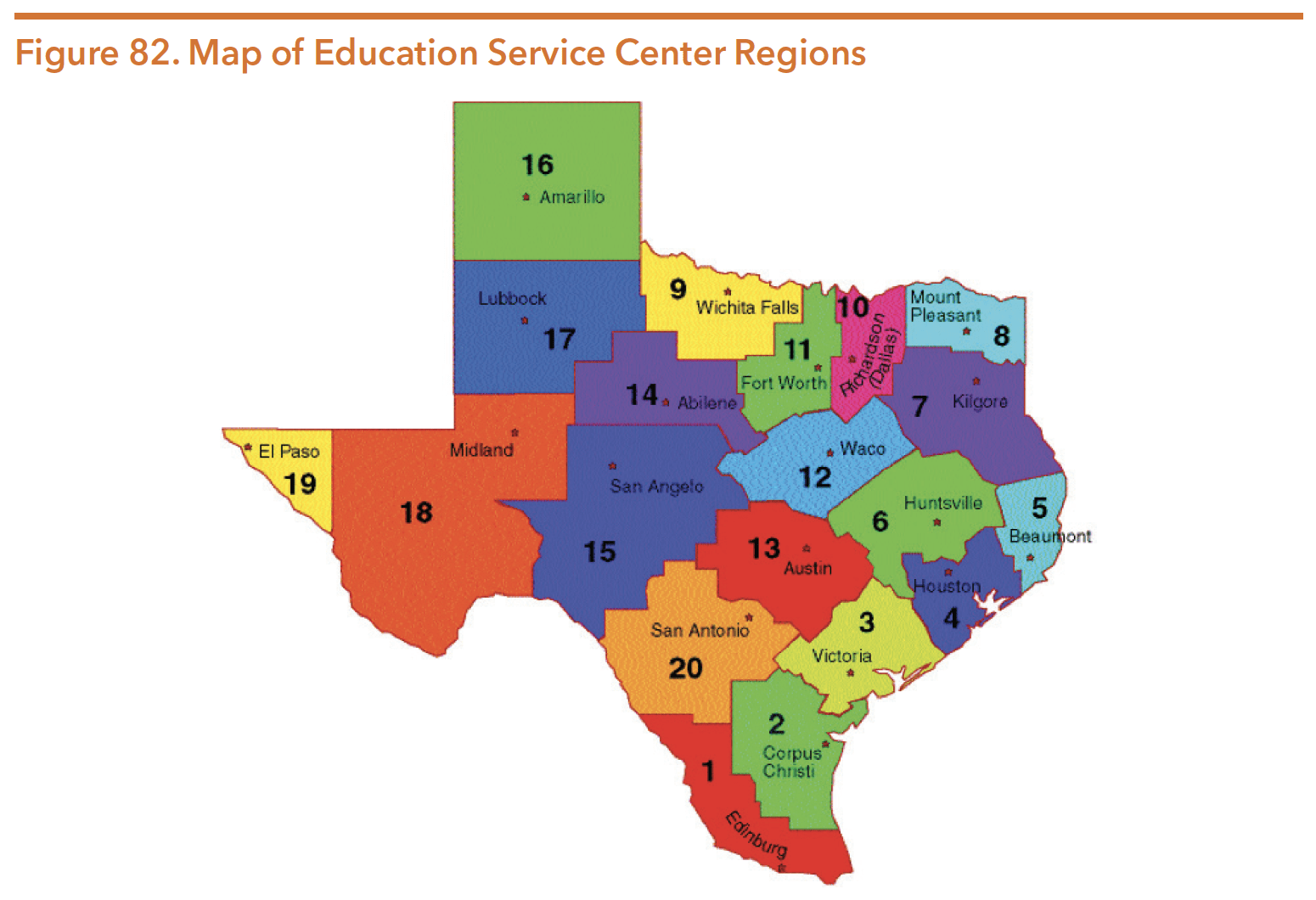

EDUCATION SERVICE CENTERS

Created in 1967, 20 regional educational service centers in Texas provide services, support, and technical assistance to all school districts throughout the state in a variety of areas, including special education and behavioral support. Enacted by the 75th Legislature, ESCs are required to assist school districts in improving student performance in each region of the state, enable school districts to operate more efficiently and economically, and implement initiatives assigned by the legislature or the commissioner. A map of service center regions is shown in Figure 82.

Source: Texas Education Agency. (2016). Education Service Centers Map. Retrieved from http://tea.texas.gov/regional_services/esc/.

ESCs specialize in specific topic areas and services, in addition to providing resources, support, programmatic assistance and general expertise to school districts or schools statewide. For example, the Region IV Education Service Center in Houston specializes in Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports with the goal of enhancing the education experience for all students by addressing the needs of students with behavior challenges. Additionally, the Region XIII Education Service Center in Austin has a Behavior Team that includes general and special education specialists who focus on providing campuses with workshops, consultations, and technical assistance for behavioral supports. During the 86th legislative session, House Bill 19 (Price/Watson) passed requiring LMHAs to employ a non-physician mental health professional as a mental health and substance use resource for school districts. While not providing direct services, the professional will be located at the ESC as a resource for schools to:

- Increase school personnel awareness and understanding of mental health, substance use, and their co-occurrence, as well as resources available;

- Assist in implementation of programs and initiatives; and

- Facilitate optional monthly trainings.

A total of $23,750,000 was allocated to ESCs for Core Services in the 2020-21 biennium, with the same amount requested for the 2022-23 biennium. ESCs do not possess tax levying or bonding authority and rely on grants and contracts for funding. Revenues are received from three primary sources: state funds, federal funds, and contracts with school districts. The ESC infrastructure supports schools in complying with IDEA and, according to the required report from Rider 34, saved public and charter schools over $122 million during the 2016-2017 school year. These savings are a direct result of the products/services provided by ESCs to LEAs across Texas. Annual savings are mainly a result of school districts increased access to cheaper products and services through ESCs (as opposed to the open market or running those programs internally) and reduced transportation and staffing costs provided through distance learning opportunities (as opposed to in-person trainings). A total of 1,132,528 individuals were trained through ESCs in 2019, up from 949,616 trained in 2017. For 2022-23 TEA expects to continue training an estimated 885,000 individuals per year through the state’s 20 ESCs.

Special Education Services in Texas

Schools are accountable for the academic performance of all students, including those with disabilities such as serious emotional issues or mental health conditions. When academic performance is impacted due to a student’s disability, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) requires schools to provide special education and related services based on an individualized educational plan (IEP). This may include mental health treatment and supports. One of the main purposes of IDEA is to ensure that children with disabilities have a free and appropriate public education (FAPE) that emphasizes special education and related services designed to meet their unique needs and prepare them for further education, employment, and independent living. Special education means specially designed instruction to meet the unique needs of a child with a disability. Related services are special services needed to support students’ special education services so they can make progress to meet their academic and functional goals. Related services can include services such as occupational therapy, physical therapy, speech/language therapy, counseling services, orientation and mobility services, and/or transportation services.

Special education services and supports provided are determined through an annual Admission, Review and Dismissal (ARD) meeting that typically includes the student, the student’s parents and/or caregivers, any mental health professionals involved in the child’s care, and school personnel including at least one of the child’s regular and special education instructors. The ARD meeting is an essential part of creating, updating, amending, and improving the individualized education plan on an ongoing basis. Students’ parents may request an ARD meeting any time they believe one is necessary. The IEP is the organizing framework and plan used to specify goals, supports,and interventions to help the student experience stability and success in the classroom. Schools are required by law to provide therapy services exactly as they are documented in the IEP. Schools cannot use personnel shortages, absences, or lack of funding to deny services. If the school fails to deliver services as documented in the IEP, the child may be eligible to receive “compensatory” services, including make-up services in the summer or private therapy paid for by the school.

Between 2004 and 2014, the population of Texas students receiving special education services decreased from 11.7 percent to 8.5 percent. The decrease in the proportion of students enrolled in special education services in Texas led to a Houston Chronicle series revealing an 8.5 percent benchmark implemented by the state in 2004 which subsequently led to a U.S. Department of Education investigation which concluded with directives for TEA to reform special education in Texas.

FEDERAL INVESTIGATION ON TEXAS’ SPECIAL EDUCATION SERVICES

For years, Texas was only identifying a very low percentage of school-age children as having special education needs, largely because of an 8.5 percent target implemented by TEA in 2004. An estimated 8.7 percent of school-aged children in Texas were identified as having special education needs in the 2015-16 school year. The percentage of children in Texas schools identified as eligible for special education services was far lower than in other states with the national average being about 13 percent.

In a 2016 series of articles in the Houston Chronicle, Texas was found to be limiting the number of students identified as eligible for special education services. The report by Brian Rosenthal alleged that TEA had systematically denied special education services to children across Texas by implementing an 8.5 percent target for children with disabilities served in school districts. The Chronicle disclosed that the benchmark was implemented in 2004, while TEA was facing a $1.1 billion state budget cut, and that it has effectively led to a denial of “vital supports to children with autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, dyslexia, epilepsy, mental illnesses, speech impediments, traumatic brain injuries, even blindness and deafness.”

The Houston Chronicle report prompted a federal investigation by the U.S. Department of Education. In 2017, the Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) within the U.S. Department of Education released a monitoring report that found three specific areas where TEA failed to comply with the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act:

1. TEA failed to ensure that all children with disabilities residing in the state who are in need of special education and related services were identified, located and evaluated, regardless of the severity of their disability, as required by IDEA.

2. TEA failed to ensure that a free appropriate public education was made available to all children with disabilities residing in the State in Texas’s mandated age ranges (ages 3 through 21), as required by IDEA.

3. TEA failed to fulfill its general supervisory and monitoring responsibilities as required by IDEA to ensure that independent school districts throughout the state properly implemented the IDEA’s child find and FAPE requirements.

Beginning in November of 2016, TEA began to address concerns expressed by OSEP. Actions included:

4. Issuing a letter to every independent school district in the state reiterating their “Child Find responsibilities” under the IDEA;

5. Coordinating a series of listening sessions throughout the state which were attended by both OSEP and TEA staff;

6. Governor Abbott, with the Texas Legislature, implemented SB 160 (85th, Rodriguez/Wu) prohibiting the use of school performance indicators to solely measure total number or percentage of enrolled children receiving special education and related services under the IDEA.

Following the full 15-month investigation, the U.S. Department of Education released their full report in January 2018. The investigation concluded that Texas failed to ensure students with disabilities were properly evaluated and that the state failed to provide an adequate public education for students with disabilities. According to The Texas Tribune, the report found that TEA was “more likely to monitor and intervene in school districts with higher rates of students in special education, creating a statewide system that incentivized denying services to eligible students” and that “school district officials said they expected they would receive less monitoring if they served 8.5 percent of students or fewer.” Further, school administrators delayed federally required evaluation of students suspected of having disabilities, often by providing intensive academic support. The report outlined corrective action for TEA to take including documentation of special education evaluation practices, developing a plan to evaluate previously denied students and directing educators on how to identify students with disabilities.

STRATEGIC PLAN FOR SPECIAL EDUCATION IN TEXAS

In 2018, TEA worked with various stakeholders across Texas to develop the Strategic Plan for Special Education in Texas. The plan lays out activities aimed at improving special education programs in Texas, including monitorting, training support and development, and student and family engagement. The majority of the strategic plan is funded through federal IDEA funding and state discretionary funds. This plan addresses the state’s role of monitoring and providing support and technical assistance to districts. There are no requirements for districts beyond what has been, and remains, a requirement of federal and/or state law.

The plan along with TEA’s progress in completing the activities in the plan can be found at https://tea.texas.gov/academics/special-student-populations/special-education.

ELIGIBILITY FOR SPECIAL EDUCATION SERVICES

Special education services encompass a wide range of interventions. Children can become eligible for these services by receiving a diagnosis for a specified condition or with general diagnosis of developmental delay, and as a result of the disability, need special education and related services to benefit from education. Figure 83 shows the various mental health diagnoses, behavioral conditions, and developmental disabilities that qualified 587,987 students in Texas for special education services in the 2019-20 school year.

Note: “Other” includes Other Health Impairment, Auditory Impairment, Non-Categorical early childhood, Orthopedic impairment, Visual impairment, Deaf/blind and Traumatic Brain Injury.

Data obtained from: Texas Education Agency. (March 2020). 2019-2020 Special Education Reports: All Texas Public Schools Including Charter Schools, Students Receiving Special Education Services by Primary Disability, PEIMS Data 2019-20. Retrieved from https://rptsvr1.tea.texas.gov/adhocrpt/adser.html

During the 2019-20 school year, over 36,000 Texas students were identified as having serious emotional disturbance — roughly 6 percent of all students identified as eligible for special education services. Nationwide, students served under IDEA have a drop out rate of 21 percent, which students identified as having serious emotional disturbance have the highest drop-out rate (38.7 percent) among students receiving special education or general education. However, there are students who receive special education based on other primary disabilities (e.g., intellectual disabilities and autism) who also have mental health needs, such as depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, attention deficit disorder, and more.

Eligibility for IDEA school-based mental health services for serious emotional disturbance is based on the student exhibiting one or more of the following characteristics to a marked degree over an extended period of time, in ways that adversely affect the student’s educational performance:

- An inability to learn that cannot be explained by intellectual, sensory, or health impairments

- An inability to relate appropriately to peers and teachers

- Inappropriate types of behaviors or feelings under normal circumstances

- A general mood of unhappiness and depression

- A tendency to develop physical symptoms, pains, or fears from personal or social problems

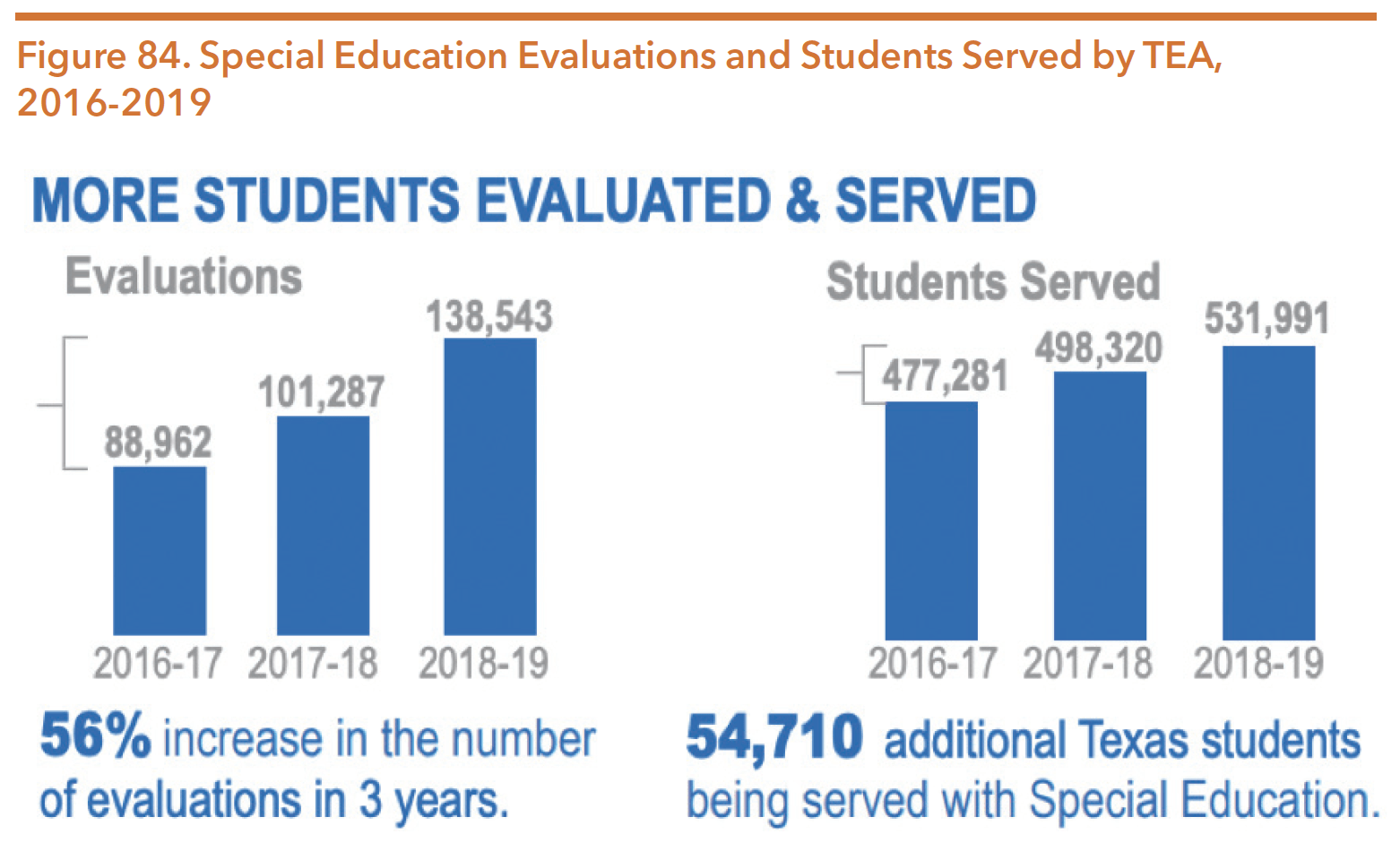

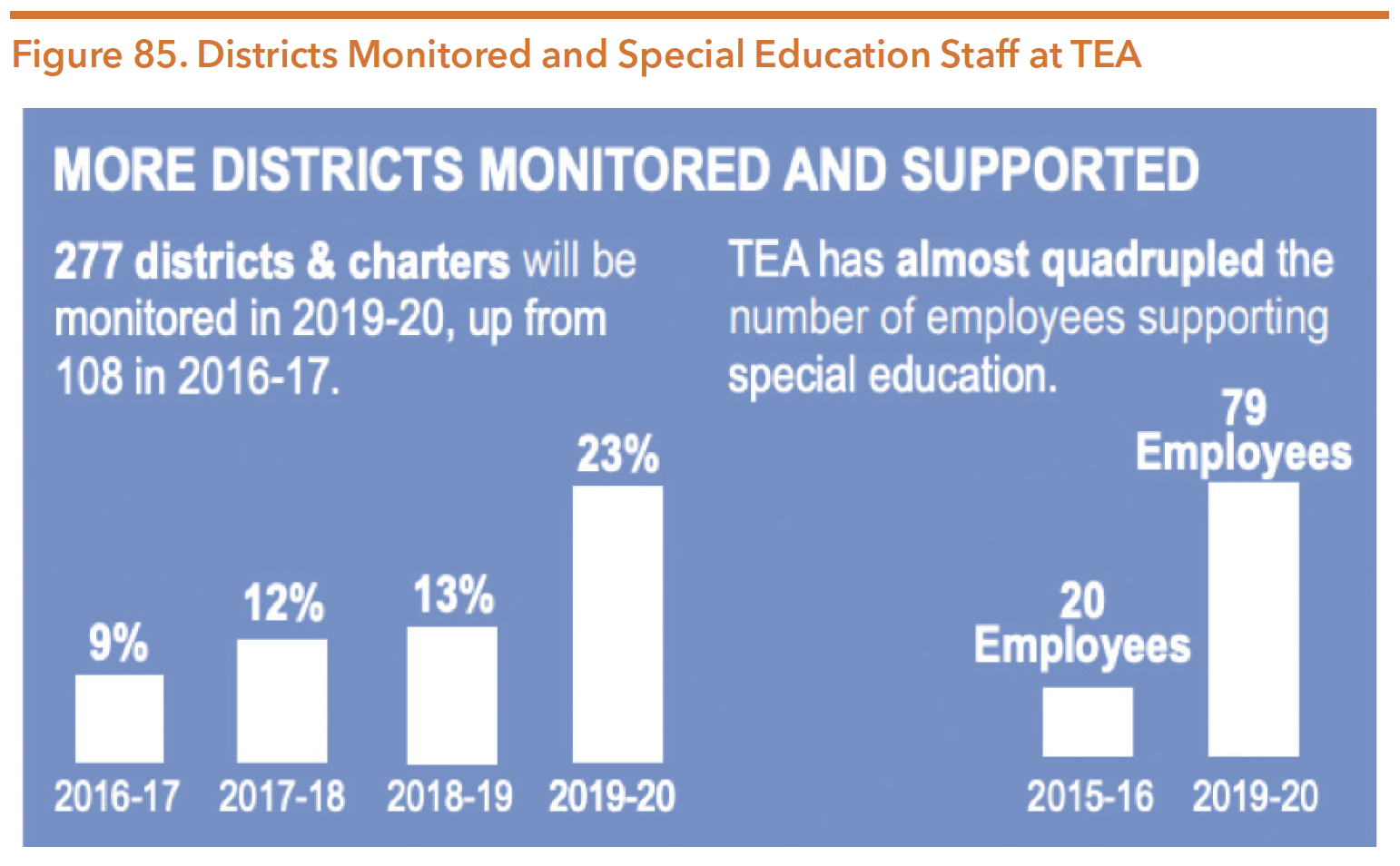

When determining whether special education services will be provided, school personnel seek evidence that the student’s behavior and need for services is not the result of a temporary reaction to adverse yet normal situations at home, in school, or in community situations. According to TEA, the number of students evaluated and served, as well as districts monitored and supported in order to serve these students has been a priority for the agency, illustrated in Figure 84 and Figure 85.

Source: Texas Education Agency. (2020). 2018-2019 Pocket Edition. Retrieved from https://tea.texas.gov/sites/default/files/2018-19%20Pocket_Edition_Final.pdf

Source: Texas Education Agency. (2020). 2018-2019 Pocket Edition. Retrieved from https://tea.texas.gov/sites/default/files/2018-19%20Pocket_Edition_Final.pdf

FUNDING FOR SPECIAL EDUCATION SERVICES

During the 2019-20 school year, roughly 7.1 million public school students received special education services across the U.S —over 14 percent of all students nationwide. During the same year, only 10.8 percent of the student population in Texas received special education services.

Funding for the “Students with Disabilities” strategy within TEA has gradually increased in recent years, with $2,108,308,102 budgeted for the 2016-17 biennium, $2,227,210,464 for the 2018-19 biennium, and $2,232,210,464 for the 2020-21 biennium. TEA has requested $2,163,495,650 for the 2022-2023 biennium, with federal funding accounting for 93.6 percent of the total requested funding.

SPECIAL EDUCATION FOR EARLY CHILDHOOD – DEVELOPMENTAL DELAYS

Because children’s brains are growing and their behaviors are constantly changing, it can be difficult to diagnose a young child with a psychological condition. There are also children without a mental health diagnosis who may still benefit from early intervention services. To bridge the gap for young children who do not have a specific diagnosis and may not receive services before entering school in kindergarten, IDEA allows for children between the ages of three and nine to qualify for special education services under a broader diagnostic category called “developmental delay,” as long as the diagnosis is made using proper instruments and procedures. The following types of diagnostic categories are designated as developmental delays at the federal level:

- Physical development

- Cognitive development

- Communication development

- Social or emotional development

- Adaptive development

States have the authority to decide what to call the “developmental delay” category, how to define it, and what ages to include as eligible. However states are not authorized to require a local education agency (LEA) to adopt or use the “developmental delay” term. Texas calls this developmental delay category “Non- Categorical Early Childhood (NCEC).” It includes children between the ages of three and five who have “general delays in their physical, cognitive, communication, social, emotional or adaptive development(s).”Because of delays, these children are in need of special education and related services. Children who fall under the NCEC category are provided services through a program called Preschool Program for Children with Disabilities (PPCD). PPCD services are provided at no-cost by the public school systems in a variety of settings such as pre-kindergarten, resource classrooms, self-contained classrooms, or community settings such as Head Start and pre-school. In addition to becoming eligible for PPCD services through the NCEC category, children in Texas may also qualify for PPCD under the following specific diagnoses:

- Intellectual disability;

- Emotional disturbance;

- Specific learning disability; and

- Autism.

EMERGING ADULTS

In recent years, Texas made efforts to bridge the gap in services and supports for students with special needs transitioning out of high school, known as “emerging adults”. To assist students who receive special education services with a successful transition from school to appropriate post-school activities, such as postsecondary and vocational education or integrated employment and independent living, schools must begin individual transition planning with students and their families by age 14. Schools are required to identify needed courses and related services for postsecondary education and to develop adult living objectives through each student’s IEP. The availability, comprehensiveness, and quality of transition services available in Texas vary widely across the state. Individual school districts, TEA, HHSC, and other state agencies make transition information available through a central website: www.transitionintexas.org.

The 85th Legislature passed HB 748 (Zaffirini/Allen) to update transition planning to reflect new state alternatives to guardianship. The bill updates the factors the ARD committee must consider regarding whether a student has sufficient exposure to supplementary services to help the student develop decision-making skills. The bill requires TEA to update the Texas Transition and Employment Guide with information about long-term services, community supports, and alternatives to guardianship. Additionally, the bill requires TEA to develop and post a list of services and public benefits available to an adult student.

Positive School Climate

Cultivating well-being at schools includes a wide array of school-wide practices that improve the school climate, including the availability of mental health services. According to TEA, a positive school climate “is the product of a school’s attention to fostering safety; promoting a supportive academic, disciplinary, and physical environment; and encouraging and maintaining respectful, trusting, and caring relationships throughout the school community no matter the setting.”

Additionally, utilizing trauma-informed education, positive behavior interventions and supports (PBIS), restorative discipline practices, and social emotional learning (SEL) so that all students and teachers are impacted positively, can create an overall supportive school community where students feel connected and safe. Providing a multi-tiered system of support through implementing strategies and supports that cultivate a positive school climate not only helps students and teachers feel safe and supported but also improves academic achievement.

Increasing mental health education, services, and supports in schools is an important component to improving school climate. Integration of mental health into schools can encourage normalizing discussions, discourage stigmatization, increase access to care, and provides opportunity for early identification and intervention, especially in rural schools where mental health resources in the community are more scarce.

Better integration has been shown to help increase recognition that mental health is a part of overall health rather than stand-alone items. By increasing knowledge, attitudes around mental health may improve, stigmatization may be assuaged, and the ability to recognize and appropriately respond to a mental health concern may be gained by students and educators. When students are socially, emotionally, and mentally well, they are able to better engage in their learning. Mental health initiatives and services are related to increased test scores, commitment to school, attendance, grades, and graduation rates, while also reducing truancy and disciplinary rates.

MENTAL HEALTH SUPPORT SYSTEMS FOR SCHOOLS

Mental health supports and services vary between individual schools and districts, often dependent on availability in the community or schools’ resources. Additionally, workforce issues and community or school leadership buy-in create additional obstacles for mental health professionals to be staffed within schools. For students being served through special education with individual education plans (IEPs), mental health services are required by law to be provided for students if those services are part of their IEP. Although the availability of mental health supports and services in school is not required, some schools have implemented programs and initiatives that support student mental health, as well as create a more broad, positive school climate. This next section describes the mental health supports, services, and related programs available statewide.

COORDINATED SCHOOL HEALTH MODEL

Texas school districts are required to provide a coordinated school health program by law that coordinates education and services related to physical health, mental health education, substance abuse education, phyiscal education and activity, and parental involvement. House Bill 18 (86th, Price/Watson) was responsible for expanding the coordinated school health programs to include mental health and substance use education.

TEA utilizes CDC’s Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC) framework for addressing health in schools. According to DSHS, “the WSCC model focuses its attention on the child, emphasizes a school-wide approach, and acknowledges learning, health, and the school as being a part and reflection of the local community.” The WSCC model Is an expansion and update of the Coordinated School Health Model, previously utilized by TEA. TEA is required to make one or more coordinated school health programs available to each school. The curriculum for the programs are directed by a mandatory, multidisciplinary team, known as the School Health Advisory Council (SHAC). SHAC members are appointed by the school district to serve and make recommendations for the district’s Coordinated School Health program.

The WSCC model includes the following components:

- Physical education and physical activity

- Nutrition environment and services

- Health education

- Social and emotional school climate

- Physical environment

- Health services

- Counseling, psychological and social services

- Employee wellness

- Community involvement

- Family engagement

HOLISTIC APPROACHES TO STUDENT WELL-BEING AND NEEDS

Addressing students’ needs in the classroom often extends beyond their learning. For a student experiencing trauma or other difficult life events such as family conflict or a natural disasater, learning can be difficult for them. When a child feels unsafe, frightened, or overwhelmed, their brain releases stress hormones, which places them in a state of “fight, flight, or freeze.” Typically, our brains and bodies subside and return to a a normal state. Unfortunately, this isn’t always the case when exposed to intense and stressful events or prolonged adversity, such as abuse, exposure to violence, parental substance use, or not having a safe and stable home. During this state, the brain prioritizes survival, so the events a child is currently experiencing, or has experienced in the past, interfere with thinking, learning, and behavior.114 Too often, unidentified mental health conditions or trauma are perceived as “bad” behavior, and punitive discipline practices are implemented. Exclusionary discipline practices have developmental, behavioral, academic, and high financial costs. The alternative models of intervention discussed in this section can support the social and emotional development of students and address their needs, while remaining more cost-effective than the resource-intensive exclusionary discipline practices (i.e., suspension and expulsion) that are often used in Texas public schools. This section will focus on five specific models and frameworks:

- Multi-Tiered Systems of Support

- Social and emotional learning

- Trauma-informed care

- Restorative justice (also known as restorative discipline)

Public schools in Texas are increasingly shifting their practices to be proactive, coordinated approaches to meet the behavioral and academic needs of all students. While some students with mental health needs require tailored interventions and trained professionals, there are also intervention models that provide a more holistic approach to supporting the needs of all students within a school system. These initiatives generally include campus-wide prevention activities, targeted early intervention for students identified to need support, and individualized services for students with complex needs. Texas is among a number of states promoting positive approaches to preventing mental and emotional problems in children.

Multi-Tiered Systems of Support

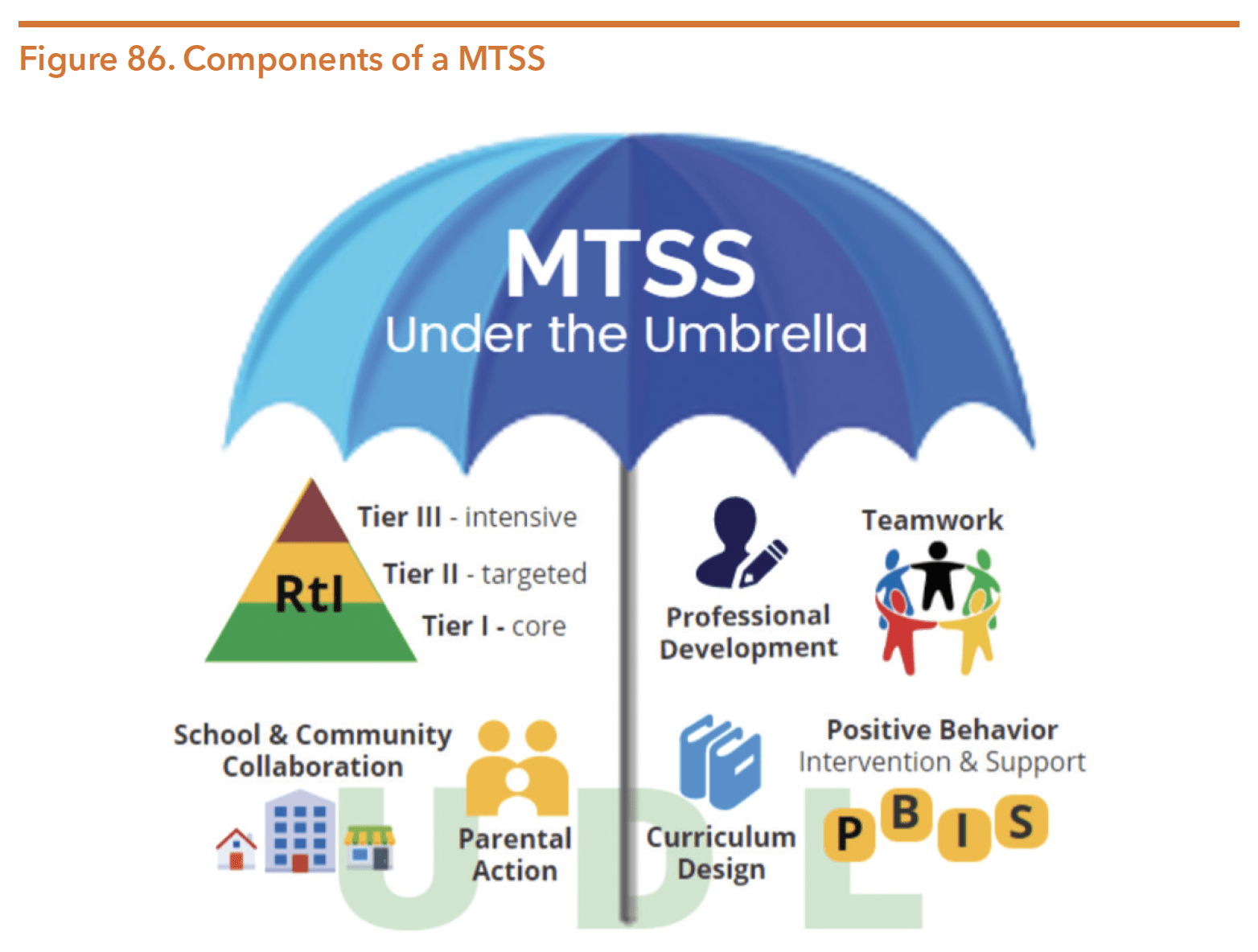

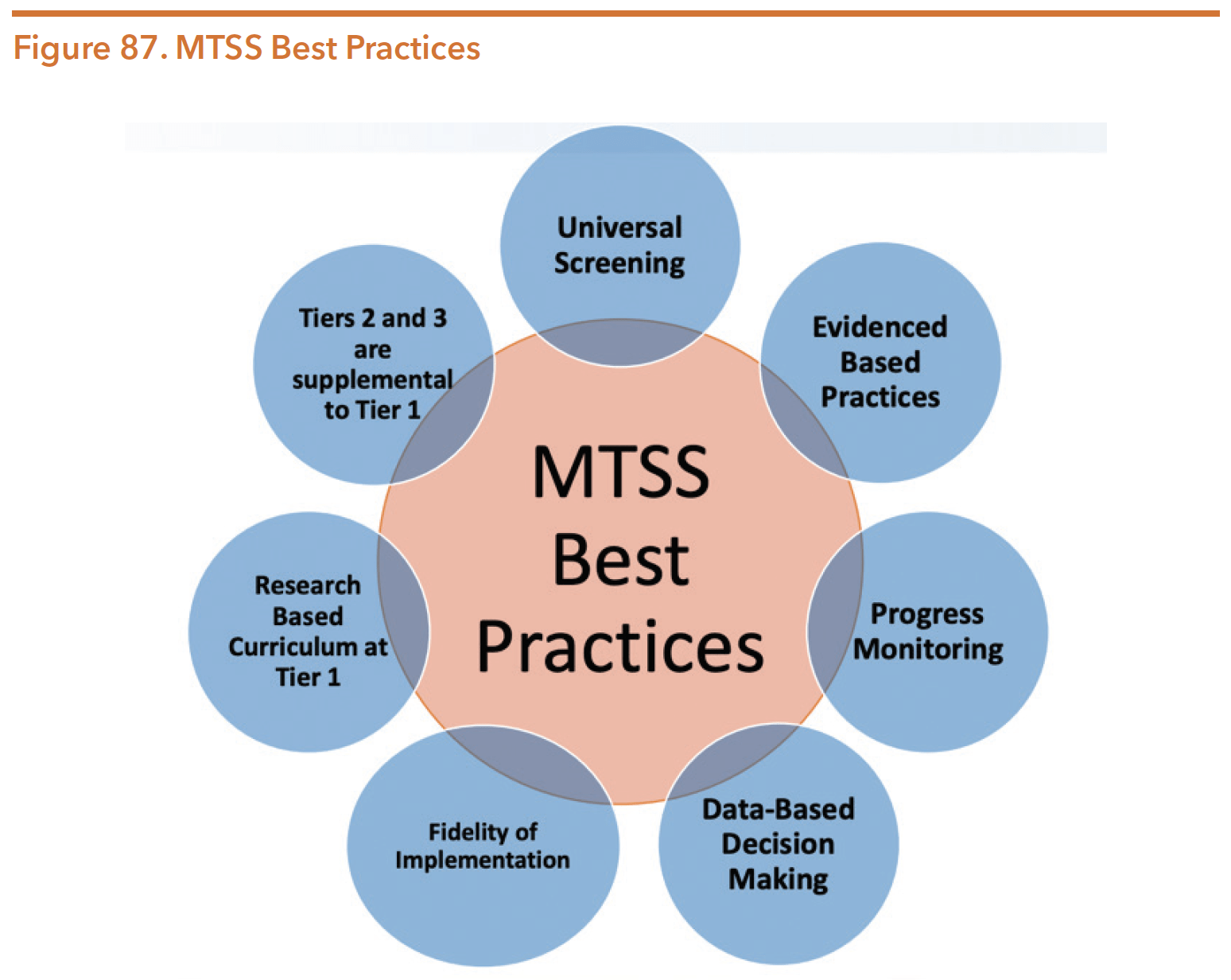

A Multi-Tiered System of Support (MTSS) is a data-driven, problem-solving framework to improve outcomes for all students. MTSS is not a curriculum, nor is it an intervention. It is simply a framework of how to identify and address school-wide needs in a way that is proactive and data-driven. MTSS relies on a continuum of evidence-based practices matched to student needs. According to TEA, MTSS encompasses supports for the whole child, and takes into account academics, behavior, and social/emotional supports. MTSS is also a research-based framework for the systemic alignment of initiatives, resources, staff development, prevention, intervention, services, and supports. Figure 86 illustrates MTSS what is encompassed within a MTSS. Figure 87 shows MTSS best practices.

Source: University of Florida, Cedar Center. (n.d.) Muti-tiered system of support chapter. Retrieved from https://ceedar.education.ufl.edu/mtssudldi-professional-development-module/mtss-chapter/#toggle-id-7

Source: Prater,S. Lee, C., Wilk, L., & Solano, F. (n.d.). Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS) questions and answers [PowerPoint]. Retrieved from https://tea.texas.gov/sites/default/files/TEA%20MTSS%20QA-Final_accessible%20PPT.pdf

Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports

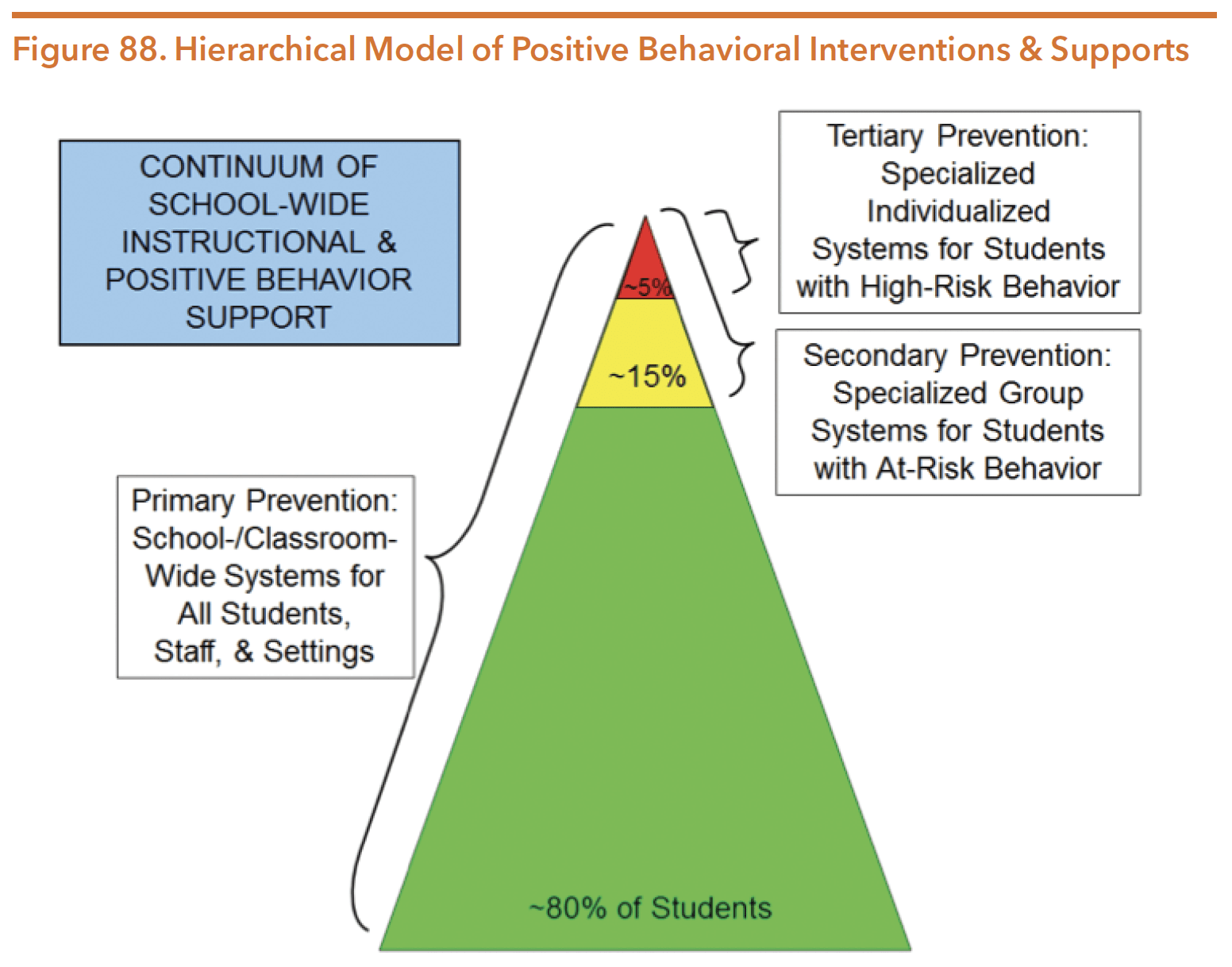

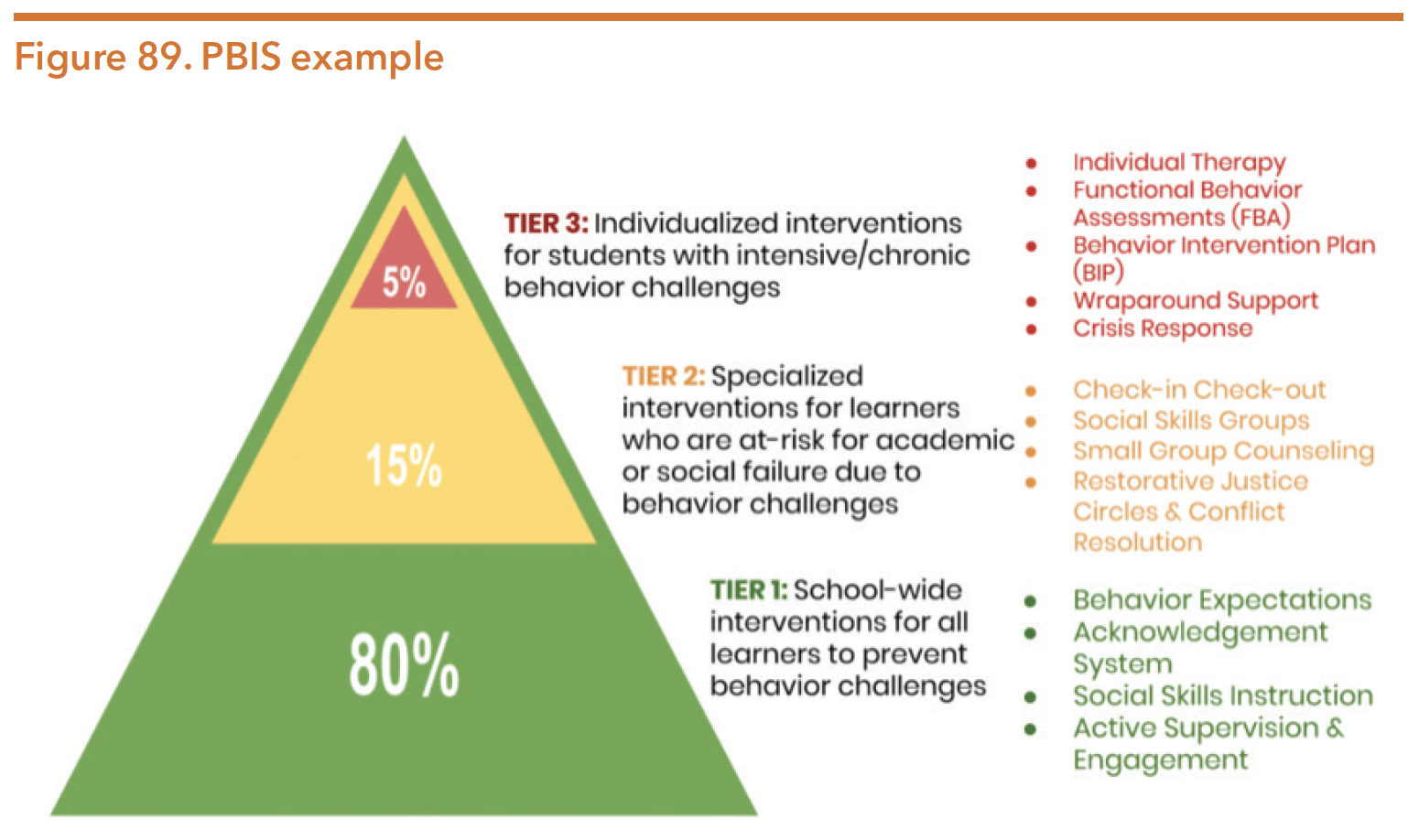

A well-known example of a tiered systems under the MTSS umbrella is positive behavioral interventions and supports (PBIS). Figure 88 illustrates the basic framework of PBIS. Figure 89 shows a more in-depth example of what types of services, interventions, and supports may be encompassed within each tier.

Source: U. S. Department of Education & Office of Special Education Programs’ Technical Assistance Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports. (2010). Implementation blueprint and self-assessment: Positive behavioral interventions and supports. Retrieved from https://www.pbis.org/Common/Cms/files/pbisresources/SWPBS_ImplementationBlueprint_vSep_23_2010.pdf

Source: Montery Pennsylvanis Unified School District. (2020). MTSS and PBIS. Retrieved from https://www.mpusd.net/apps/pages/index.jsp?uREC_ID=1012305&type=d&pREC_ID=1322797

PBIS is an evidence-based framework that uses a three-tiered approach to teach and reinforce appropriate behaviors for all students. PBIS programs are designed to replace a punishment-oriented system with a campus culture based on respect, open communication, and individual responsibility.

The program’s three tiers consist of the following:

- Tier 1: The primary prevention tier is the largest of the three, focusing on interventions for 80 to 90 percent of students. In this tier, school staff uses a curriculum to teach social skills and expectations that all students and school personnel are expected to follow.

- Tier 2: The secondary prevention level focuses on the 10 to 15 percent of students who have risk factors such as exposure to violence, a history of trauma, or the loss of a loved one that causes them to have a higher-than-normal risk of developing mental health needs. This tier focuses on developing skills and increasing protective factors for students and their families.

- Tier 3: The tertiary prevention level focuses on the 1 to 5 percent of the student population who need an in-depth system of supports. This tier is focused on providing comprehensive, individualized interventions for students with the most severe, complex or chronic issues.

TEA recommends that school districts utilize PBIS to address student behavior but public schools are not currently required to use PBIS or other related approaches. During the 85th legislative session, Texas passed three bills that were related to PBIS:

1. HB 4056 (Rose/Lucio) – requires the inclusion of PBIS on the state’s best practice list.

2. SB 179 (Menendez/Minjarez)- requires that if a district does develop any practices or procedures related to PBIS, it must include them in their student handbook and district improvement plans.

3. HB 674 (Johnson/Garcia)– allows schools to develop positive behavior programs for students in grade levels below grade three as a disciplinary alternative.

4. Continuing to improve integration of PBIS into Texas schools, the 86th Texas Legislature passed House Bill 18 (Price/Watson), which included a number of provisions inclusive of PBIS including:

- Allowing PBIS to be part of school staff development training;

- Requiring schools’ district improvement plans to include provisions for evidence-based practices that address PBIS and integrate best practices on trauma-informed care; and

- Requiring schools to develop practices and procedures concerning PBIS.

Technical assistance to implement PBIS is available through the network of regional educational service centers and the Texas Behavior Support Initiative (TBSI). TBSI was designed to build capacity throughout the state for the provision of positive behavioral interventions by assisting schools in developing and implementing a wide range of behavior strategies and prevention-based interventions.

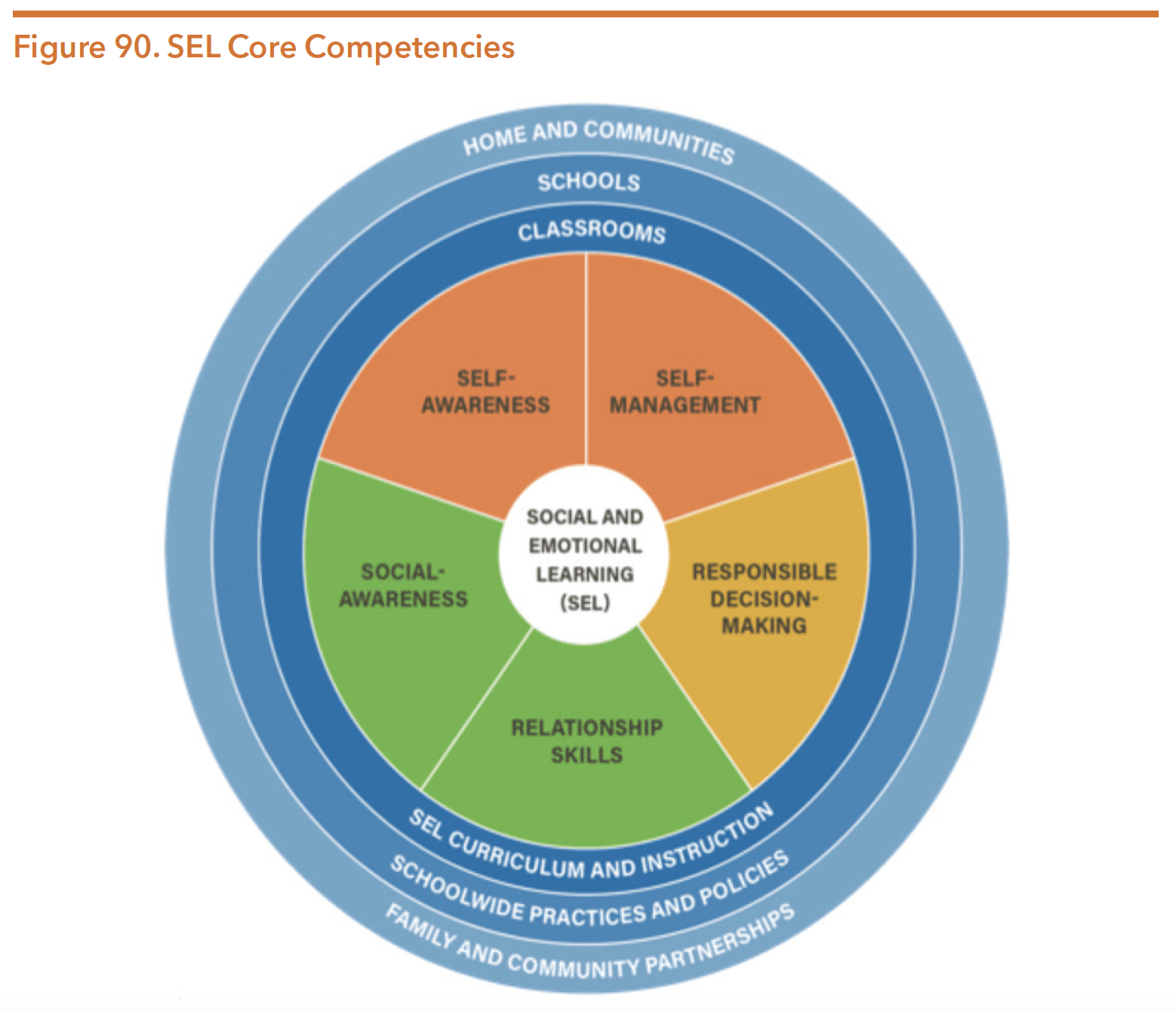

Social and Emotional Learning

According to TEA, social and emotional learning (SEL) is not a specific program, but a framework that “involves the process of understanding and applying the knowledge, attitudes and skills necessary to understand and manage emotions, set and achieve goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships and make responsible decisions.” Figure 90 illustrates the core competencies of SEL.

The main goals of the SEL framework are to:

- Help students work well and productively with others;

- Develop positive relationships;

- Cope with their emotions;

- Appropriately settle conflicts with consideration for others;

- Work more efficiently and effectively; and

- Make decisions that are safe, ethical, and responsible.

Source: Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL).(n.d.). What is SEL? Retreived from https://casel.org/what-is-sel/

As a result of HB 18 (86th, Price/Watson), Texas schools are required to develop practices and procedures related to SEL, defined as “building student skills related to managing emotions, establishing and maintaining positive relationships, and responsible decision-making.” Schools can choose from a variety of proven, effective SEL programs, but it is not necessary to hire additional staff to implement SEL—the primary costs of an SEL program are related to staff training and student surveys. SEL programs can be implemented from preschool through high school and can improve student functioning in a number of areas. Additionally, SB 504 (86th, Seliger/Beckley) included social-emotional counseling tools as a possible component of online postsecondary education and career counseling academies for school counselors.

Austin Independent School District (AISD) in Central Texas has committed to incorporate SEL in its schools—one of the first districts in the country to make this commitment. AISD began implementing SEL in 2013, and by the 2015-16 school year, all 129 AISD campuses were implementing the SEL program. In 2017, AISD began an SEL 2.0 initiative to deepen their SEL work within Austin ISD and the community over the next three to five years. A number of other schools districts across Texas have begun SEL initiatives including Dallas, El Paso, Houston, Round Rock, Keller, Friso, Arlington, and Northwest.

National research on the effectiveness of SEL has found:

- Improved academic performance (13 percent increase in achievement scores after SEL)

- Greater motivation to learn and increased time studying at home

- Reduced negative classroom behaviors (e.g., less noncompliance, aggression, and disruption)

- Fewer disciplinary referrals

- Reduced bullying of students with disabilities

- Reduced reports of depression, anxiety and stress

- Decrease in school dropout rates

- For each $1 invested into SEL, there was an $11 return

Trauma-Informed Care

Children who have experienced trauma often see the world as a threatening place, and this can lead to anxious behaviors that interfere with the child’s ability to learn and interact socially with their peers. Creating a trauma-informed environment within schools requires that all staff understand how trauma affects an individual and incorporates that understanding of trauma into every aspect of how they educate and interact with students. An organization that is trauma-informed understands the vulnerabilities and triggers of trauma survivors and uses this understanding to ensure that staff do not re-traumatize individuals with the organization’s approach to working with them. In a trauma-informed environment, children feel safe and accepted by their peers, even when they make mistakes.

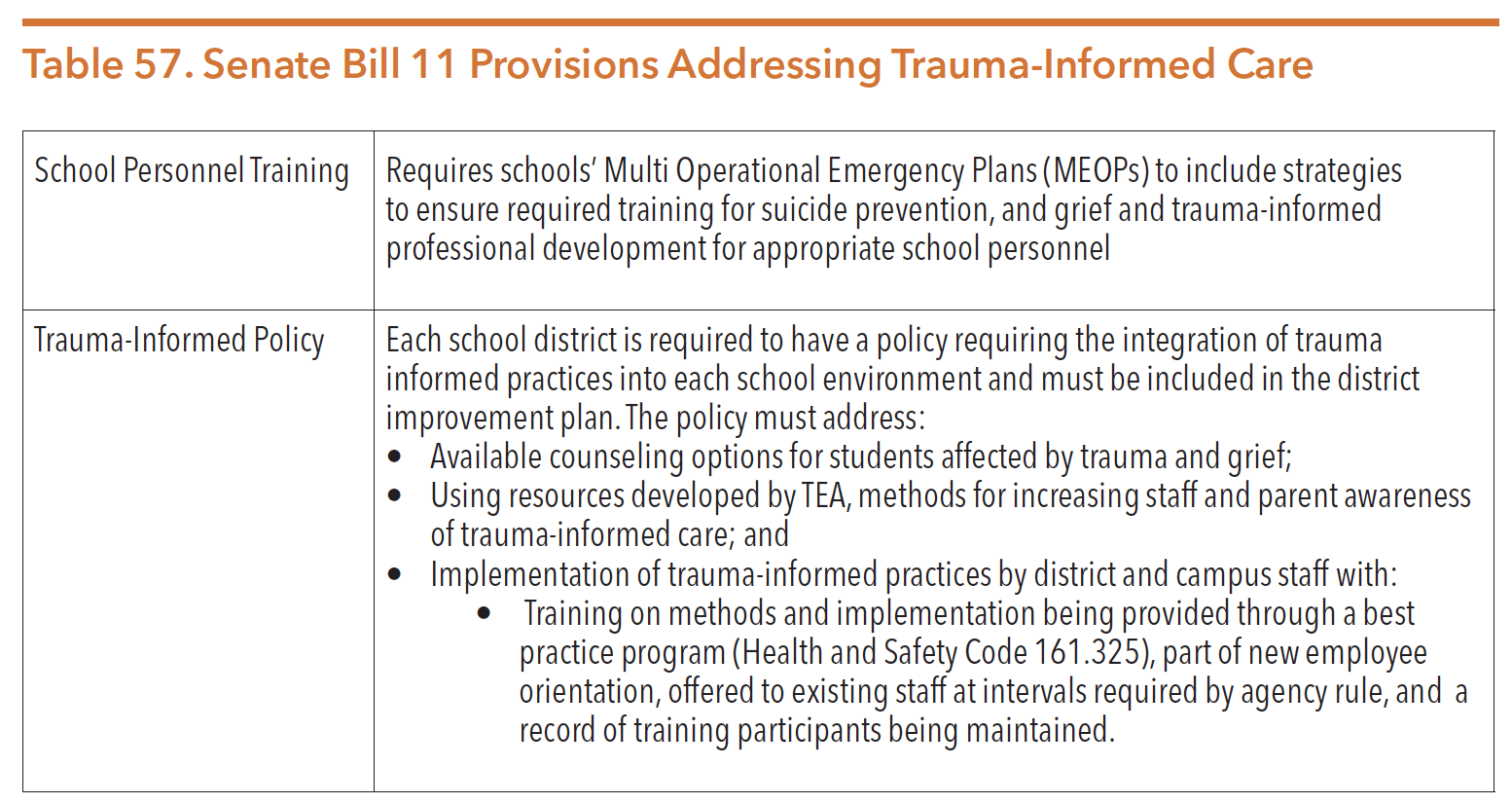

In the 86th legislative session, trauma-informed training and integration within schools gained attention through the passing of HB 18 (Price/Watson) and Senate Bill 11 (Taylor/Bonnen). The requirements of these bills are summarized below in Table 56 and Table 57.

Source: The Hogg Foundation for Mental Health. (January 2020). Policy brief: School climate legislation from the 86th legislative session. Retrieved from https://hogg.utexas.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/FINAL_86th-Lege_Policy-Brief_School-Climate.pdf

Source: The Hogg Foundation for Mental Health. (January 2020). Policy brief: School climate legislation from the 86th legislative session. Retrieved from https://hogg.utexas.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/FINAL_86th-Lege_Policy-Brief_School-Climate.pdf

Mental health treatment practices (including trauma-informed care) and school-based mental health practices have yet to catch up with the reality that people with IDD can also live with serious mental health conditions including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Individuals with IDD have a greater opportunity for experiencing traumatic events than the general population. Yet behaviors associated with any resulting mental health challenges, such as PTSD, can manifest differently than in the general population and often go unrecognized. It is important that we continue to improve the accuracy of assessment tools and the effectiveness of a variety of therapies and treatments for individuals with IDD, keeping recovery at the forefront.

Too many IDD systems of care (including schools) continue to focus on controlling and managing challenging behaviors without adequate consideration of the potential for underlying mental health conditions or the impact of trauma as the cause of the behaviors. The focus of school interventions and treatment has historically been to develop behavior management plans to promote compliance or the use of medications to control the behaviors. In both cases the treatment is targeting the behavior and not the actual mental health condition, making recovery unlikely and doing little to reduce or remove barriers to learning. To better educate school personnel on mental health concerns for students with disabilities, HB 18 (Price/ Watson) allows for staff development to be inclusive of identifying and supporting students with both disabilities and a mental health condition. HB 19 (Price/Watson) requires a non-physician mental health professional employed by the LMHA to be located in the regional ESCs. The mental health professional will be responsible for facilitating optional training on a monthly basis, on the effects of grief and trauma for children with intellectual or developmental disabilities.

The Hogg Foundation for Mental Health at The University of Texas partnered with the National Child Traumatic Stress Network to develop a training curriculum and toolkit, Road to Recovery: Supporting Children with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Who Have Experienced Trauma. The toolkit was developed over two years with contributions from national mental health experts and IDD experts. The toolkit is designed to be a two-day train-the-trainer resource and is available free of charge at http://nctsn.org/products/children-intellectual-and-developmental-disabilities-who-have-experienced-trauma. The toolkit includes six modules:

1. Setting the stage

2. Development, IDD, and Trauma

3. Traumatic Stress Responses in Children with IDD

4. Child and Family Well-being and Resilience

5. IDD Trauma-informed Services and Treatment

6. Provider Self-Care

The toolkit includes a facilitator’s guide, videos, participant manual, case vignettes, board game/activities, slide kit, and supplemental materials. This training would be beneficial to anyone working with or supporting children with IDD. To access the toolkit requires creating an account on the website, however, the toolkit is free to anyone with an account.

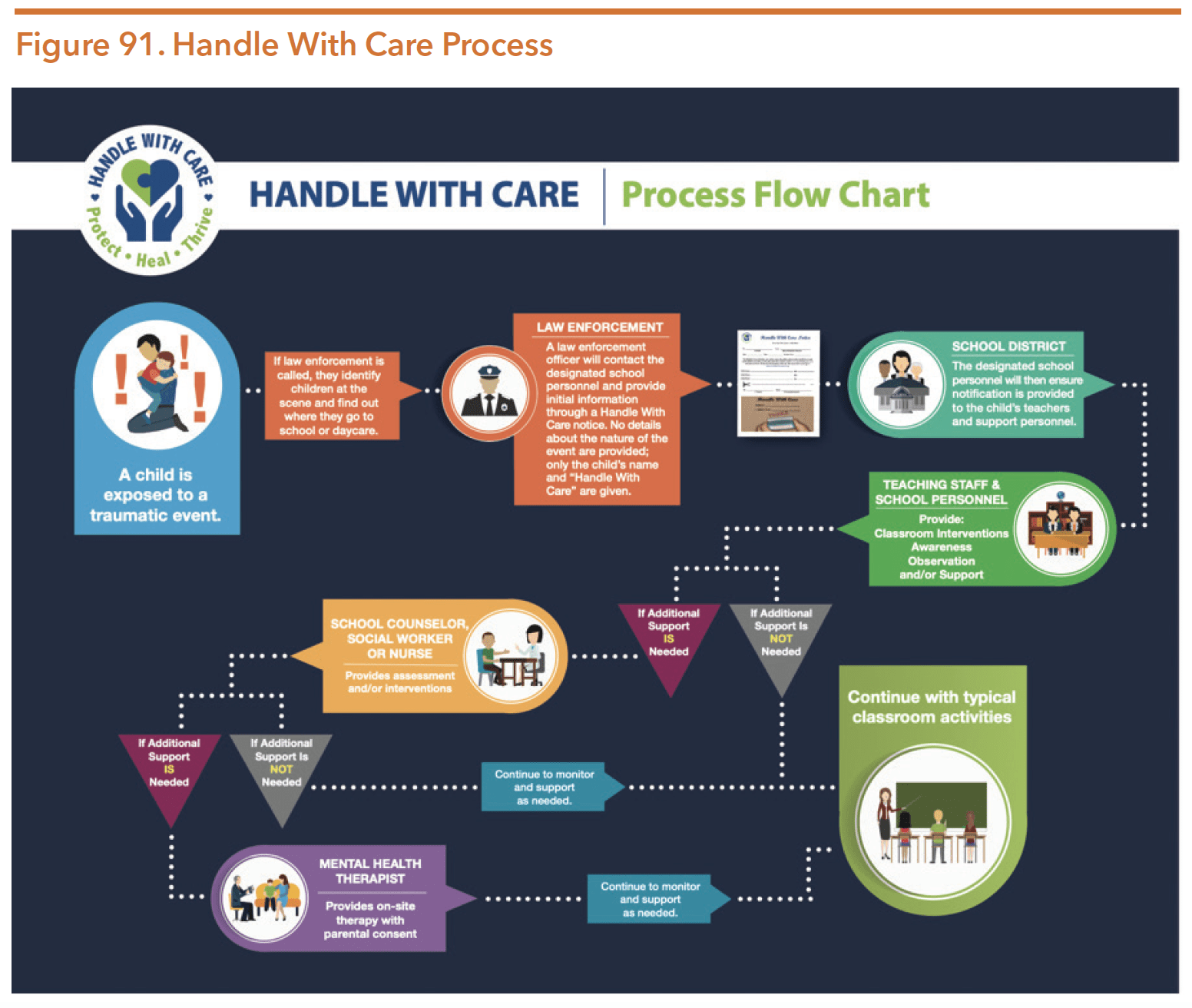

Handle With Care

In 2013, Mary C. Snow West Side Elementary School in Charleston, WV piloted a program, “Handle With Care” that addressed supporting students in schools who have been present to a potentially traumatic experience at home or in the community. Handle With Care is a partnership between law enforcement and schools. The law enforcement officer at the scene of a crime/violence/abuse, identify if children are at the scene. At a minimum, the child’s name and school is sent confidentially by the officer to the child’s school before the next day with no more information given except for the three words “handle with care.” Figure 91 outlines the Handle With Care process.

“Handle With Care” is trauma-sensitive and identifies interventions that may help mitigate the negative effects of trauma on children. The program allows teachers and schools to be aware if a student has experienced trauma at home or in the community. This supports the child and the school if there are negative behaviors, so that more appropriate support, interventions, or mental health services may be offered rather than punitive punishment.

As of August 2019, over 65 cities across the US had implemented a Handle With Care program at their school districts. In January 2019, three ISDs piloted the program with San Antonio Police Department (SAPD): San Antonio ISD, East Central ISD, and Northeast ISD. During the pilot program from January 2019 to August 2019, there were approximately 80 notifications sent out from the East Patrol service area. After the success of the program, the three districts permanently implemented the program district-wide, and additional districts joined as well.

All SAPD service areas were given the training and ability to make notifications from their in-car laptops. Through the Region 20 ESC, an invitation for area schools and law enforcement agencies to be a part of the program was extended. As of April 2020, the collaboration across San Antonio encompassed all Bexar County public schools, as well as some private and charter schools, four police departments, and the San Antonio Fire Deparment. From September 2019 to March 2020, approximately 338 notifications were sent out citywide.

To continue the work during the closing of schools due to COVID-19, Handle With Care was able to continue due to schools’ innovative initiatives. For example, San Antonio ISD created a dashboard of virtual contacts with students, inclusive of Handle With Care notifications.

Source: Handle With Care Maryland. (n.d.) Handle with care: Process flow chart. Retrieved from https://handlewithcaremd.org/docs/Handle%20WIth%20Care%20Flow%20Chart.pdf

Restorative Justice Framework

Restorative justice is a prevention-oriented framework that views misbehavior as more than an infraction of the school’s rule by holding the student accountable in a safe, non-court setting, leading to better outcomes for students, victims, schools, and communities. In the school setting, restorative justice involves not only the misbehaving student but the person harmed and the community around them. Including the community in the process fosters a feeling of responsibility for the student, thereby strengthening and uniting a community around their young people. A restorative justice framework can be applied to the entire school setting by focusing on the impact of student misbehavior on others, and how that student and their school community can recover from the incident in a healthy way. Institute for Restorative Justice and Restorative Dialog (IRJRD) describes Restorative Discipline as “a relational approach to fostering school climate and addressing student behavior that prioritizes belonging over exclusion, social engagement over control, and meaningful accountability over punishment.”

According to a Texas Criminal Justice Coalition report, “from the requirement of taking responsibility for the wrongdoing, to making a sincere apology, to developing a plan for restitution satisfactory to the victim, to ultimately following through on that plan, professionals and students agree: far more accountability is required of a student making amends through a restorative justice model than one who is sent home via suspension or expulsion.”

Restorative justice can be implemented by using methods such as group conferencing, healing circles, check-ins, and mediated victim offender dialogue (VOD). Restorative justice helps the student consider the consequences of their actions, and also encourages empathy by using age-appropriate, feeling-centered language. For example, using restorative circles in the classroom allows students to talk openly and honestly about student misbehavior and the effects it has on the classroom or entire school. A restorative circle allows the students to use community values and group expectations to collectively address the problem and make an individualized plan for restitution. While the circles take place in classrooms, the framework is intended to be used by the entire school so that the overall school community is improved by allowing school culture to be improved as a whole rather than narrowly focusing on changing individual behaviors. Similar to PBIS and SEL, the restorative justice framework offers schools a more proactive and strengths-based framework for managing behavior and promoting academic and social-emotional growth both inside and outside of the classroom.