*Note: If you find the text on some of the images blurry or hard to read, right-clicking the image and then selecting “open image in new tab” may improve the issue.

Policy Concerns

- Assess the impact of COVID-19 on TDCJ operations and protect people in TDCJ care from exposure to COVID-19.

- Divert people with mental illness who commit low-level offenses away from correctional facilities and into community-based treatment settings. Improve the state courts’ use of civil commitment as a diversionary tool to reinforce civil intervention before an individual ever enters the criminal justice system.

- Improve mental health screening, safety, and suicide prevention procedures in correctional settings.

- Decrease the use of prolonged solitary confinement, repeated restraints, and other aversive interventions on persons incarcerated with mental illness.

- Increase early identification of persons with co-occurring mental illness and substance use disorder, and connect them with needed community-based services.

- Increase early identification of people who may have an intellectual and/or developmental disability (IDD).

- Increase external oversight within prisons, jails, and other incarceration settings to ensure that people with mental health conditions experience constitutional and humane conditions, without solitary confinement.

- Improve access to mental health treatment including therapy and psychiatric medications within correctional facilities, especially in rural jail facilities.

- Implement civil commitment as an option to divert individuals with a mental illness or intellectual disability even after an individual enters the criminal justice system.

- Expand access to specialty courts, like mental health courts, drug courts, and veterans’ courts, to divert people with mental health concerns and substance use issues away from correctional settings.

- Improve mental health and substance use awareness and decrease stigma through cross-system collaborations of law enforcement agencies, local jail facilities, courts, attorneys, and local mental health authorities (LMHA) in rural areas.

- Improve the mandates of the Sandra Bland Act by implementing telehealth and telemedicine mental health services inside of jail and prison facilities for people with lesser acute mental illnesses.

- Improve continuity of care for people with mental illness as they transition from incarceration settings to communities, including case management, therapy, medications, outpatient treatment plans, and reentry peer support services.

Fast Facts

- Language matters. The use of thoughtful, humanizing, and destigmatizing language helps to restore the identity and dignity of a person recovering from mental illness who has been incarcerated. The person returning to the community is a human being who also happened to have a mental illness and was involved with the justice system. Thus, we discourage using “prisoner,” “felon,” or “offender” as these terms wrongly emphasize the symptom (incarceration) over the condition (mental illness). We recommend using respectful language such as “justice-involved,” “consumer” (instead of patient), or “person in jail” which are consistent with treatment and a person’s capacity to change.

- A study conducted from February 2011 to May 2012 found that 1 out of every 7 people in state and federal prisons (14 percent) and 1 out of every 4 people in jails (26 percent) reported having a serious mental illness. Additionally, 37 percent of prisoners and 44 percent of jail inmates had previously been told they had a mental health condition.

- Texas incarcerates 563 people per 100,000 residents. In 2020, it is projected that the justice-involved population will be 145,553 in adult incarceration and 1,209 in juvenile secure facilities, with another 334,525 people on parole or probation.

- Texas has the 7th highest imprisonment rate in the U.S. and African Americans in the state are four times more likely than Whites to be justice-involved.

- In FY 2017, the average cost of incarcerating an individual in a state facility was $62.25 per day. By comparison, the cost for an individual on parole supervision was $4.30 per day and cost for community supervision was $3.72 per day.

- TDCJ unit and psychiatric care expenses represent the majority healthcare costs at $194.5 million, representing 52.8 percent of its total expenses. Other healthcare costs, including hospital care, accounted for $138.9 million or 37.7 percent. Pharmacy services were at $35.3 million or 9.6 percent of the total expenses.

- In January 2020, Texas county jails had a total bed capacity of 93,704, with 65,825 individuals in their facilities. Of that number, 65.6 percent of the individuals in Texas county jails had not been convicted of a crime.

- In 2018, researchers estimated that people are booked into jails over 10.6 million times in the U.S. every year, and about 615,000 people are in a jail facility on any given day. If those statistics hold true for Texas, then over one million people pass through Texas jails each year.

- In 2018, 44 percent of the 2,286 written grievances submitted by people in county jails to the Texas Commission on Jail Standards involved complaints regarding medical services, including mental health services.

- In the 85th legislature, the Texas House of Representatives passed legislation that opened the door for peer support specialists to be trained, certified, and appropriately compensated through Medicaid reimbursements. Peer support services and providers assist individuals experiencing mental health or substance use disorders by helping the individuals focus on recovery, wellness, self-direction, responsibility, and independent living.

TDCJ and Local Jail Acronyms

- ACLU – American Civil Liberties Union

- MHJDP – Mental health jail diversion pilot

- BAMBI – Baby and Mother Bonding Initiative

- MHPD – Mental health public defender

- CCQ – Continuity of care query

- MRIS – Medical Recommended Intensive Supervision

- CIT – Crisis intervention team

- OCR – Outpatient competency restoration

- CJD – Criminal Justice Division

- OMHM&L – Office of Mental Health Monitoring and Liaison

- CMBHS – Clinical management for behavioral health services

- PAMIO – Program for Aggressive Mentally-Ill Offender

- CTI – Critical time intervention

- PREA – Prison Rape Elimination Act

- CMHCC – Correctional Managed Health Care Committee

- PRSAP – Pre-Release Substance Abuse Program

- CMI – Chronically Mentally Ill Program

- PRTC – Pre-Release Therapeutic Community

- DDP – Developmental Disabilities Program

- SAFPF – Substance Abuse Felony Punishment Facility

- DWI – Driving while intoxicated

- SAMHSA – Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

- FACT – Forensic assertive community treatment

- TCJS – Texas Commission on Jail Standards

- HHSC – Health and Human Services Commission

- TCOLE – Texas Commission on Law Enforcement

- IDD – Intellectual and other developmental disabilities

- TCOOMMI – Texas Correctional Office on Offenders with Medical or Mental Impairments

- IPTC – In-Prison Therapeutic Community

- TDCJ – Texas Department of Criminal Justice

- JCHM – Judicial Commission on Mental Health

- TDHCA – Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs

- LBB – Legislative Budget Board

- TTUHSC – Texas Tech University Health Science Center

- LMHA – Local mental health authority

- SBHCC – Statewide Behavioral Health Coordinating Council

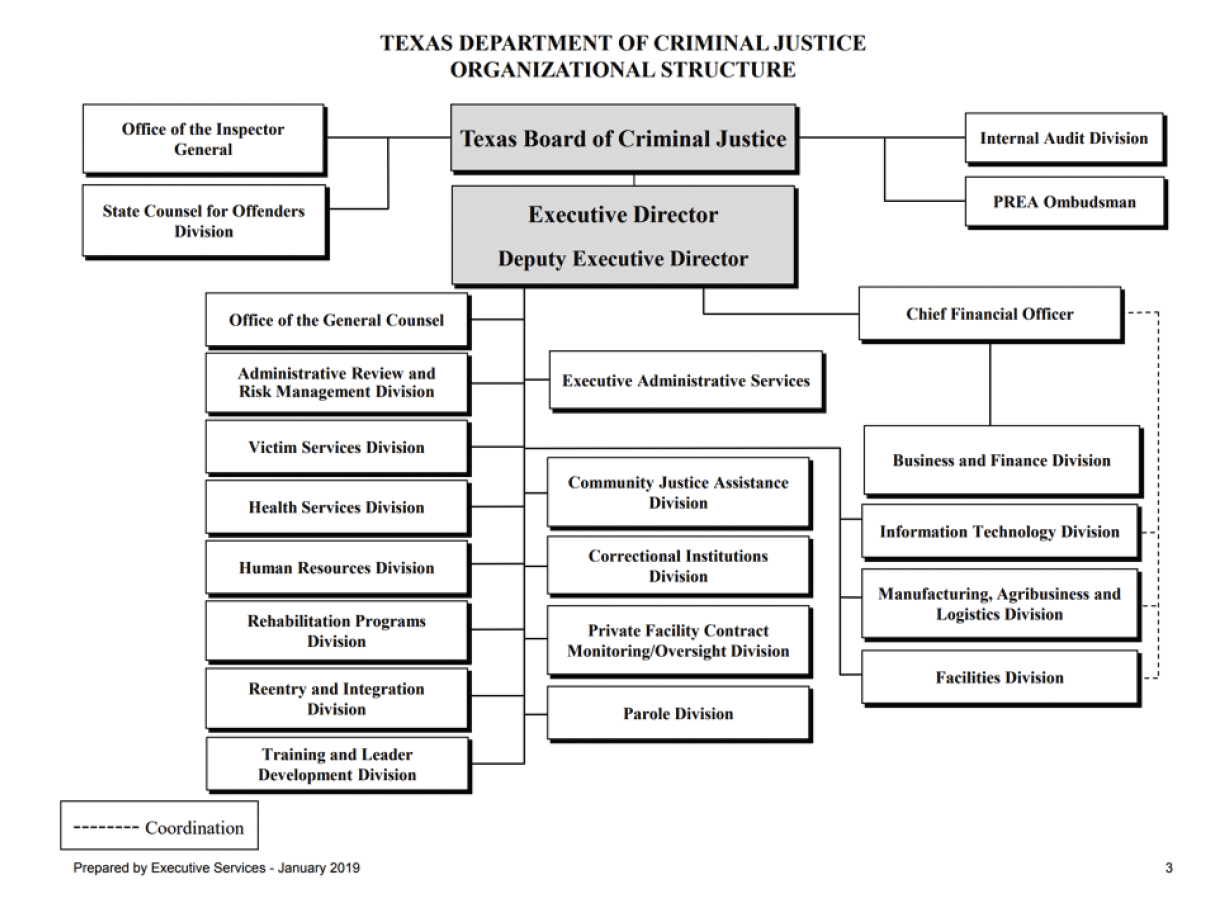

TDCJ Organization Chart

Source: Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Organizational Structure. Retrieved October, 2020 from https://www.tdcj.texas.gov/org_chart/pdfs/org_chart_tdcj.pdf

Overview

TDCJ RESPONSIBILITIES AND MISSION

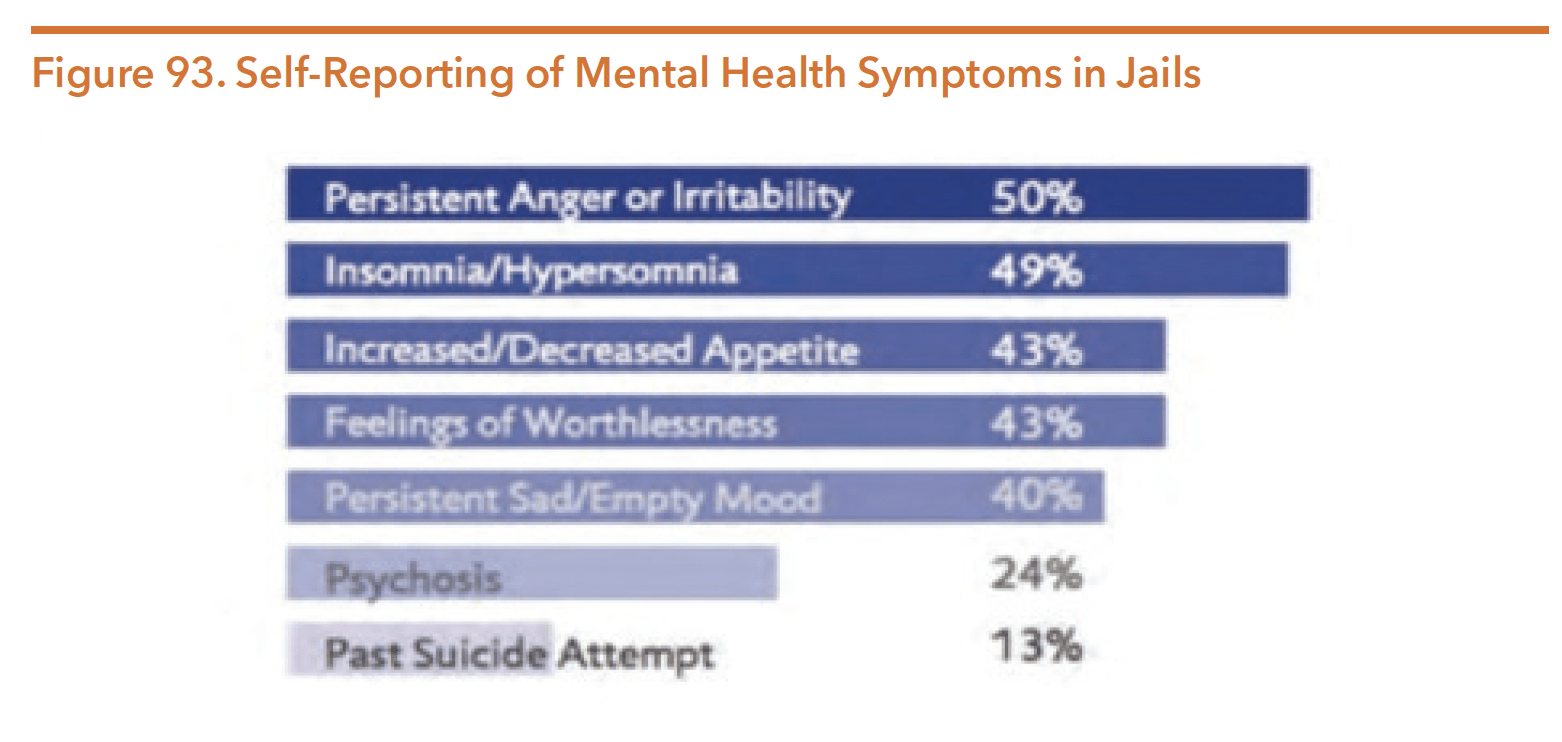

Many people involved in the Texas criminal justice system live with one or more mental health condition, and many have co-occurring substance use disorders. Additionally, those with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) represent 4 to 10 percent of the prison population, including a greater number in juvenile facilities and jails. The strong connection between mental health and the criminal justice system has not always existed. In the 1970s, only 5 percent of incarcerated persons in the U.S. had a serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Due to lack of funding in community-based treatment and support infrastructure, decades later we see the result those financial decisions. Recent studies estimate that 14 percent of people in prisons and 26 percent of people in jails experienced serious psychological distress in the preceding 30 days (in contrast to 5 percent of the general population). In 2015, about 30 percent of people in local Texas jails had at least one serious mental illness. The percentage of justice-involved individuals with less severe mental health issues, such as mild depression, is even greater; researchers estimate that over half of people incarcerated in U.S. prisons and jails have at least one mental health condition. The criminal justice system was not historically structured to provide mental health treatment and recovery services, but rather focused on punitive measures that can harm a person’s path to recovery. The figure below demonstrates that a large proportion of individuals in jails across the country self-report at least one mental health symptom.

Source: As used in Hautala, M. (2015). In the Shadow of Sandra Bland: The Importance of Mental Health Screening in U.S. Jails. Texas Journal on Civil Rights & Civil Liberties, 21(1), 98. Data derived from Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2006). Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates.

Despite the overrepresentation of people with mental illness in U.S. prisons and jails, research suggests that only 7 percent of these individuals enter the criminal justice system because of behavior linked directly to their mental illness. Instead, a justice-involved person with a mental illness’s alleged criminal behaviors are often tied to behavioral factors (such as hostility, disinhibition, or emotional reactivity) or to social factors (such as poverty and homelessness).

The extent to which serious mental illness is connected to dangerous behavior remains unclear. In some cases, it seems that mental illness may be linked to violent behavior, but research shows that this link is weak. In fact, people with mental illness only commit an estimated 4 percent of violence in the U.S. Contrary to the public fear created by highly publicized mass shootings and the predictable political discussions blaming gun violence on mental illness that often follow, people with serious mental illness commit a small proportion of homicides in which a gun is used. The vast majority of people with a diagnosable serious mental illness never engage in any violent activities. Statistical evidence shows that, in the absence of a substance use disorder, most mental illnesses are unrelated to acts of violence. Unfortunately, the science of risk assessment has not advanced sufficiently to allow researchers to identify which individuals will commit violent acts. Thus, despite publicity and public perception, studies show that the large majority of people with serious mental illnesses are never violent. Misinformation about mental illness and violence has led to further stigmatization of people living with serious mental illness.

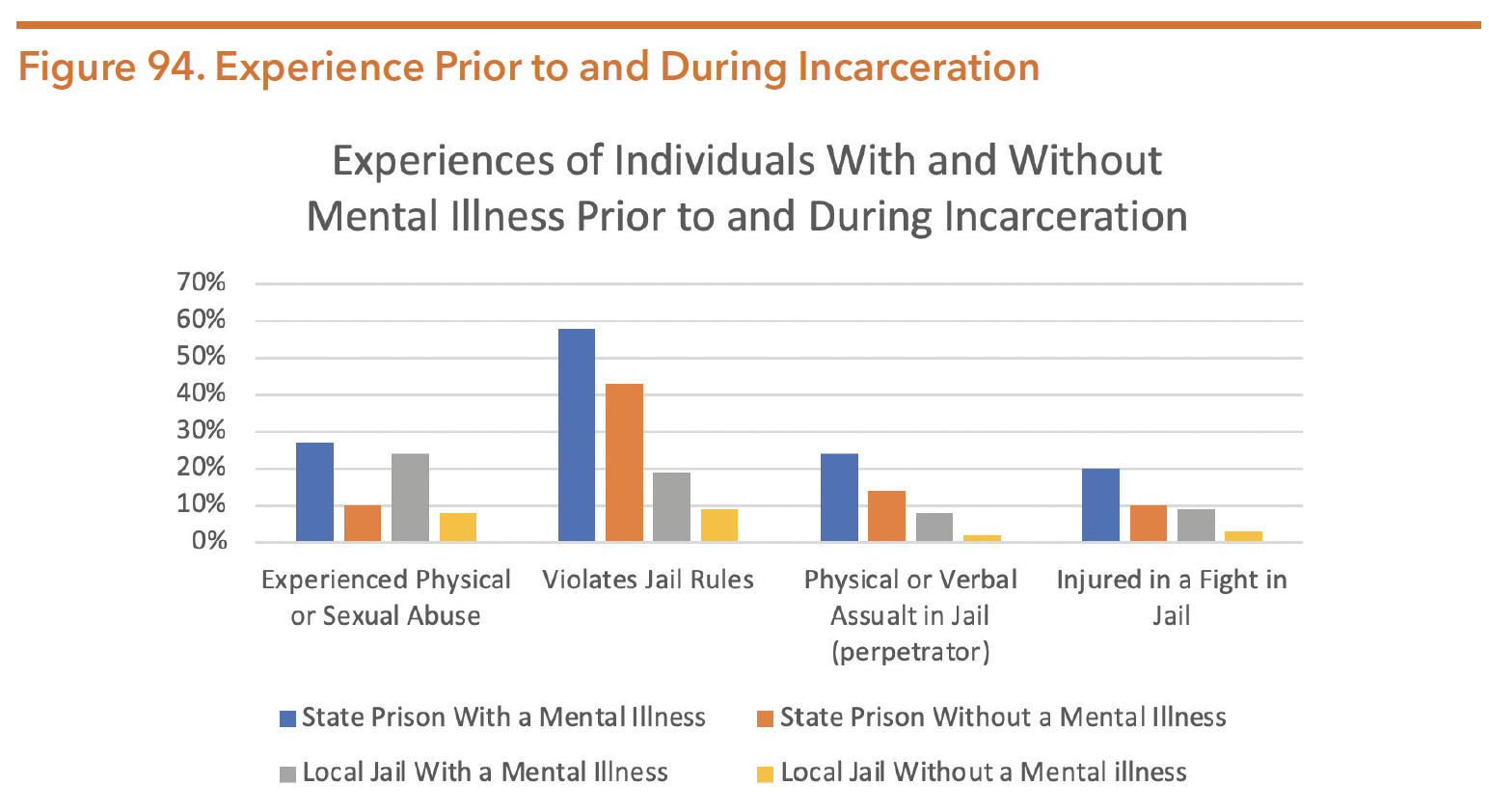

Prior to their imprisonment, justice-involved persons with mental illness are more likely than incarcerated persons without mental illness to have used drugs, experienced homelessness, or survived abuse. Once incarcerated, they often face challenges that exacerbate their mental health conditions. People with mental illness are more likely than other incarcerated populations to experience physical abuse, solitary confinement, and sexual victimization. These experiences further perpetuate the cycle of untreated illness and criminal justice involvement. The figure below demonstrates some of the challenges that people with mental illness disproportionally face prior to and during their incarceration. In addition to individual mental health impacts, the growing number of people with serious mental illness in the justice system raises important challenges concerning correctional facility management, unit security, and state, county, and local community budgets.

Source: As used in Hautala, M. (2015). In the Shadow of Sandra Bland: The Importance of Mental Health Screening in U.S. Jails. Texas Journal on Civil Rights & Civil Liberties, 21(1), 102. Data derived from Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2006). Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates. Page 1. Retrieved from https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mhppji.pdf

DISPROPORTIONALITY IN THE TEXAS CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM

In recent years, national attention has focused on remarkably high rates of incarceration in the U.S. – six to ten times greater than other industrialized nations. Strikingly, the trends in incarceration rates are independent of changes in crime rates. Much of the increase in incarceration – and much of the racial disparities of those incarcerated – are linked to behavioral health issues, particularly substance use.

The burden of imprisonment falls disproportionately on African Americans. African Americans are sentenced to state prisons at a rate 5.1 times higher than Whites. These racial disparities are not rooted in racial differences in criminality. Much of the volume and complexion of incarceration in the U.S. is linked to the “War on Drugs” and sentences related to drug possession and sales. Research identified differences in behavior concluding that White youth are more likely to engage in drug-related crime than Black youth.

Research has identified three root causes for these racial disparities:

- Policies and practices (e.g., federal drug sentencing laws mandating a minimum sentence of 5 years for distribution of 5 grams of crack or 500 grams of powder cocaine)

- Implicit bias and stereotypes in decision making (e.g., disparities in court referrals to treatment versus prison)

- Structural disadvantages in communities of color, such as higher rates of poverty, housing insecurity, and exposure to trauma (what some call the social determinants of legal engagement).

Public information on racial and ethnic disparities in county jail populations in Texas is lacking. There are significant disparities between White and Black jail populations nationally, but those disparities seem to be decreasing.

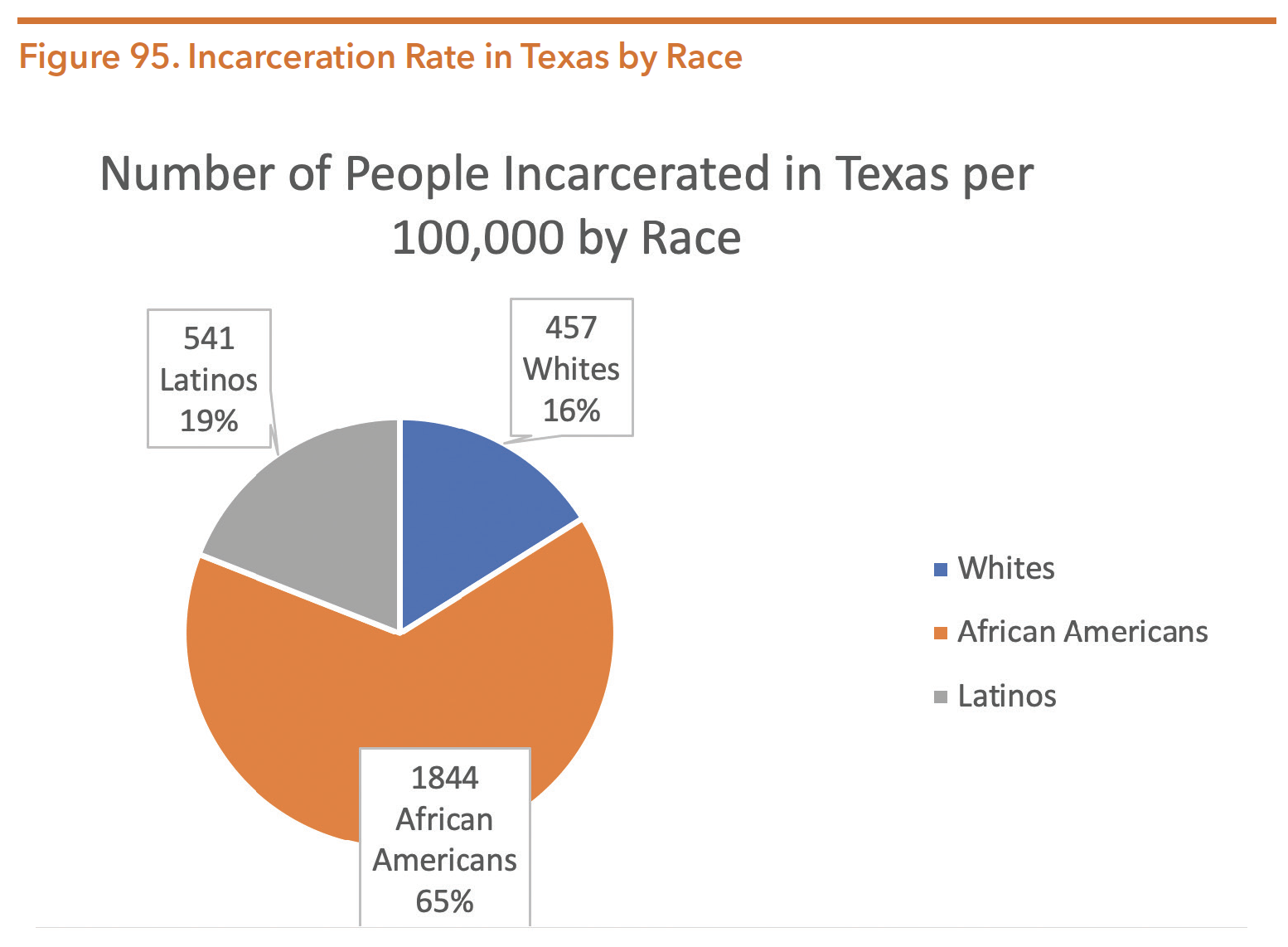

In Texas, the key racial disparities are between White and Black incarceration rates. In 2016, African Americans comprised 12 percent of the Texas population, yet were incarcerated at a much higher rate than White and Latinx individuals. Texas incarcerated 457 White and 541 Latinx individuals per 100,000, while African Americans were incarcerated at a rate of 1,844 per 100,000. The figure below depicts incarceration rates by race and ethnicity.

Source: Nellis, A. The sentencing Project. The Color of justice: Racial and Ethnic Disparity in State Prisons. Page 5. https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/color-of-justice-racial-and-ethnic-disparity-in-state-prisons/ Accessed 14 Apr. 2020.

When U.S. lawmakers declared the War on Drugs in 1975, the criminal justice system’s racial demographics shifted significantly. Major policy decisions related to minimum sentences for drug convictions disproportionately impacted communities of color across the nation. Four decades ago, 67 percent of Texas inmates were White, 12 percent Black, and 20 percent were Latinx. Today, 1 in 20 black males are incarcerated.

In Harris County (Houston), stakeholders received a MacArthur Foundation Safety and Justice Challenge grant to reduce the high jail population and address significant racial disparities in the Harris County Jail. Grant strategies include implementing a pretrial risk assessment tool to increase granting personal bonds, implementing a newly designed docket system to address the large volume of drug possession cases, and hiring a Racial Disparity and Fairness Administrator to promote training, community engagement, and data-driven decision-making.

SPECIAL CONCERNS FOR WOMEN

The U.S. incarcerates women at the highest rate in the world. Although just 4 percent of the world’s female population lives in the U.S., we account for over 30 percent of the world’s incarcerated women. Texas exceeds the U.S. rate by 45 percent. The number of women in Texas prisons ballooned over 900 percent from 1980-2016 and continues to grow each year. Women in correctional settings have distinct and specialized mental health needs compared to women outside of correctional facilities. Women in jail and prison are:

- Ten times more likely to be dependent on drugs than women without experience in the justice system;

- Seven times more likely to experience sexual abuse prior to their imprisonment than incarcerated males; and

- Four times more likely to experience physical abuse prior to their imprisonment than incarcerated males.

A recent survey of over 430 women in TDCJ custody reported that 55 percent of women had a mental health diagnosis, but only 27 percent had a mental health casemanager. Furthermore, 70 percent of the women had a substance use disorder, but only 21 percent reported receiving substance use treatment inside TDCJ.

COLLABORATIONS

The death of Sandra Bland and the subsequent law changes have led to a different approach on how individuals suspected of a mental illness interact with the criminal justice system. The legal community, mental health professionals, law enforcement, state agencies, courts, and nonprofit organizations meet regularly all across the state to achieve better outcomes for this population.

In 2018, the Judicial Commission on Mental Health (JCMH) began collaborating with key stakeholders including judges, LMHAs, law enforcement, attorneys, nonprofits, and anyone working with justice-involved individuals living with a mental illness. Persons with lived experience of mental health and substance use conditions also participated.

In October 2019, the Supreme Court of Texas and Texas Court of Criminal Appeals appointed twenty-two members to the JCMH Legislative Research Committee. This committee’s areas of concentration are competency restoration (including jail-based competency options), diversion, and services.

SB 362 of the 86th Legislature directed the Supreme Court of Texas to establish a task force for procedures relating to mental health in December 2019. The task force developed four areas of concentration:

- Possible technological solutions for emergency detention problems

- Standardizing common mental health forms

- Recommendations for the 87th Legislature

- Long-term policy recommendations

The Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) received a SAMHSA grant for the Texas Forensic Initiatives Team (TFIT) to identify the common system stresses. Through collaborative efforts, the mental health practitioners, clinicians, legal professionals, sheriffs, nonprofits, persons with lived experience, and HHSC staff found four priority areas:

Early identification, assessment, and treatment of those with mental health conditions and IDD;

- Address gaps and deficiencies in the competency to stand trial processes;

- Increase opportunities for competency evaluators, courts, attorneys, and other stakeholders to receive training in best-practice trends; and

- Expand resources for diversion from the criminal justice system.

Other statewide mental health and criminal justice collaborative efforts include the following:

- Justice and Mental Health Coalition, facilitated by National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI)-Texas

- Texas Council of Community Centers Annual Conference58

- Texas State of Mind by the Meadows Mental Health Policy Institute

- Texas Tech Mental Health Law Symposium

Though rural, sparsely populated counties are often constrained by a lack of resources, some counties are able to send delegates to the JCMH and other statewide collaborations.

Changing Environment

Historically, Texas has been on the forefront of criminal justice reform across the U.S. In 1987, Texas created the first agency in the U.S. designed to coordinate policies between mental health and criminal justice – the Texas Correctional Office on Offenders with Medical or Mental Impairments (TCOOMMI). Two decades later, in 2007, the 80th Texas Legislature altered the trajectory of criminal justice policy by prioritizing diversion from incarceration over the construction of new prisons. In the 85th session, legislators passed a budget that required TDCJ to close four prisons by September 1, 2017, contributing to a total of eight facility closures. In addition to mandating the four closings, lawmakers passed significant legislation to improve jail processes and created matching grants to increase diversion and reduce recidivism. Despite the prison closures, Texas still has the 6th highest imprisonment rate in the U.S.

More recently, the state has allocated $8 billion for mental health services ranging from community mental health services to substance abuse treatment, and more. Through the use of telemedicine and mental health specialty courts, individuals with mental health needs in the criminal justice system are now getting better access to treatment. Within mental health courts, participants are 50 percent less likely to be re-arrested compared to the regular criminal court system. The addition of telemedicine and telehealth in jails will offer access to services for those individuals while they await their day in court. Mandated as a part of the Sandra Bland Act of 2017, all 240 county lock-up facilities must be ready to provide mental health access, either in person or virtually, by Sept. 1, 2020.

MAJOR LEGISLATION FROM THE 86TH TEXAS LEGISLATURE

Legislation passed during the 86th Texas legislative session aligns with the Sequential Intercept Model (SIM). The SIM details different points in time when a person with a mental illness might encounter, and sometimes be diverted from, the criminal justice system. The 2019 Texas Legislature’s focus on this model builds upon the heightened awareness of mental health conditions from the 2015 Sandra Bland death. The JCHM also prioritized the SIM to address intersection points with the criminal justice pipeline and system where diversion may be possible. Several pieces of legislation focused on different intercept points.

We have divided the legislation passed during the 86th legislative session by the intercept that it impacts. Additional information on the Sequential Intercept Model is included later in this section.

COMMUNITY SERVICES (INTERCEPT 0)

SB 633 – Regional Collaborations of Rural LMHAs

SB 633 (86th, Kolkhorst/Lambert) is an initiative to increase the capacity of local mental health authorities in under-resourced areas to provide access to mental health services. Mental health authorities in rural areas of Texas will now be grouped into regions. To assist with implementation, this bill requires HHSC to develop a plan and, in collaboration with the LMHA group, to determine a method of increasing the capacity of the authorities in the local mental health authority group to provide access to needed services using existing resources of the authorities. HHSC made regional visits to all rural areas of the state to assist with asset mapping of each region’s strengths and resources. A report is required to be published on HHSC’s website by December 1, 2020.

PUBLIC HEALTH (INTERCEPT -1)

HB 2813 – Statewide Behavioral Health Coordinating Council

In the 84th Texas Legislature, a Statewide Behavioral Health Coordinating Council was established to coordinate efforts to improve mental health and behavioral health programs. HB 2813 (86th, Price/Nelson) codified what was previously enacted through a budget rider, permanently establishing the council in statute.

The following is a list of the 23 Texas entities on the Statewide Behavioral Health Coordinating Council, all of which receive funding related to mental health and/or substance use:

- Office of the Governor

- Veterans Commission

- Health and Human Services Commission

- Texas Civil Commitment Office

- Department of Family and Protective Services

- Department of State Health Services

- Texas Education Agency

- School for the Deaf

- Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center

- University of Texas – Health Science Center at

- Houston

- University of Texas – Health Science Center at Tyler

- Supreme Court of Texas

- Court of Criminal Appeals

- Military Department

- Commission on Jail Standards

- Juvenile Justice Department

- Department of Criminal Justice

- Medical Board

- State Board of Dental Examiners

- Board of Nursing

- Optometry Board

- State Board of Pharmacy

- Board of Veterinary Medical Examiners

SB 362 – Court-Ordered Mental Health Services

SB 362 (86th, Huffman/Price) reforms procedures related to court-ordered outpatient and inpatient mental health services by:

Amending procedures for early identification of a defendant suspected of having mental illness or an intellectual disability;

- Allowing a trial court to release a defendant on bail and transfer the defendant to the appropriate court for court-ordered outpatient mental health services, if the offense charged does not involve serious bodily injury;

- Allowing the dismissal of the underlying charges after the defendant complies with such treatment in certain circumstances;

- Requiring the Court of Criminal Appeals to ensure that judicial training related to court-ordered mental health services is provided at least once every year; and

- Requiring an inpatient treatment facility administrator to assess the appropriateness of transferring the patient to outpatient mental health services not later than 30 days after the patient is committed to the facility.

SB 362 (Huffman/Price) received $850,000 in appropriations for each fiscal year for implementation.

LAW ENFORCEMENT (INTERCEPT 1)

HB 3540 – Release of a Person with IDD at the Person’s Residence in Lieu of Arrest

HB 3540 (86th, Burns/Hughes) focused additional attention on persons with or suspected of having IDD who encounter the criminal justice system. The legislative intent demonstrates Texas legislators’ belief that confinement of the person in a correctional facility would be unnecessary to protect that person and others from harm. Police officers may use reasonable efforts to consult with staff at the residence and with the person regarding the decision to release. The law would apply only to a person with IDD who resided at a group home or an intermediate care facility.

INITIAL DETENTION AND COURT PROCEEDINGS (INTERCEPT 2)

HB 601 – Reporting Requirements for Persons Suspected to Have a Mental Illness or IDD

HB 601 (86th, Price/Zaffirini) clarifies that the LMHA, local intellectual and developmental disability authority, or another qualified mental health or intellectual disability expert collecting information (as directed by a magistrate) must interview a defendant and collect related information regarding a defendant’s potential mental illness or intellectual disability.

Changes through HB 601 remove potential confusion during intake into a jail. The bill also:

- Permits the interview to be done in person, by phone, or by telehealth;

- Provides for reimbursement by the county for the person or LMHA conducting the interview;

- Adds persons with, or suspected of an IDD, to the early identification procedures of Tex. Code of Crim. Proc. Arts. 16.22 and 17.032; and

- Requires a copy of any mental health records, screening reports, or similar information to accompany a defendant transferred to TDCJ.

- HB 2955 – Specialty Court Reporting

In an effort to align Texas with national practices of centralized specialty courts, HB 2955 (86th, Price/Zaffirini) moves the 200 specialty courts under the purview of the Office of Court Administration. Now mental health courts, veteran courts, and others have one judiciary oversight entity to better advance quality assurance, training, funding, research, technology, and advocacy goals.

HB 4468 – Access to Mental Health Services in County Jails

HB 4468 (86th, Coleman/Whitmire) addresses the gaps in services available in jail for a person with mental health needs. The legislation ensures that justice-involved people with less acute symptoms who do not demonstrate the likelihood of harm to self or others have access to a mental health professional within a reasonable time. If a mental health professional is not available in-person, they will be accessed through telemedicine health services, which will be required in all Texas jails by September 1, 2020.

REENTRY FROM JAIL/PRISON (INTERCEPT 4)

SB 1700 – Safe Release from County Jails

Directly after some justice-involved individuals were released from jail, there were still substantial safety risks. In some situations, individuals were released during the middle of the night, without proper clothing or any familiarity with the surrounding area. Persons with a mental illness or IDD were especially vulnerable.

In order to address these concerns, legislators filed SB 1700 (86th, Whitmire/Miller), which designates specific daytime hours (6:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m.) when any person can be released from a county jail. The bill has an exception carved out for individuals being admitted to an inpatient mental health facility or state supported living center for mental health or IDD services.

RELEVANT BUDGET RIDERS

Legislators also addressed criminal justice and mental health-related issues through riders to the budget (HB 1, 86th, Nelson/Zerwas). Budget riders do not provide new funding. Rather, they are legislative directives instructing agencies how to spend certain appropriated funds. Relevant riders are listed below.

HHSC (Article II)

- Rider 53 Screening for Offenders with Mental Impairment – directs HHSC and community centers to identify offenders with mental health conditions in the criminal justice system, collect and report prevalence data, and accept and disclose information relating to special needs offenders.

- Rider 57 Mental Health Peer Support Re-entry Program – directs HHSC to allocate up to $1 million in general revenue (GR) for the biennium to maintain a mental health peer support reentry program. Requires these programs use certified peer support specialists to ensure inmates successfully transition from jail into clinically appropriate community-based care. This rider requires a legislative report by December 1, 2020.

- Rider 58 Semiannual Reporting of Waiting Lists for Mental Health Services – requires HHSC to submit semiannual reports to the Legislative Budget Board (LBB) and the governor providing data on waiting lists and related expenditures for community adult mental health services, community children’s mental health services, forensic state hospital beds, and maximum-security hospital beds.

- Rider 59 Mental Health Program for Veterans – allocates $5 million in GR each fiscal year for the purpose of administering the mental health program for veterans. Requires a legislative report December 1st of each fiscal year. Roughly $1 million of this funding is allocated to justice-involved veterans.

- Rider 62 Mental Health Grant Program for Justice-Involved Individuals – allocates $25 million in GR each year of the biennium for administering a grant program to reduce recidivism, arrests, and incarceration for individuals with mental illness while also reducing wait times for forensic commitment. The rider also directs $5 million in GR each year to be allocated to the Harris County jail diversion program and requires each grantee to report twice annually to the Statewide Behavioral Health Coordinating Council.

HB 1, Article IX, Contingencies and Other Special Provisions

- Special Provision Sec. 18.95 Judicial Training Program – appropriates $250,000 each fiscal year in GR for the development of a training program to inform and educate judges and staff on mental health resources in the state to both the Supreme Court of Texas and the Court of Criminal Appeals.

SB 500 (Nelson/Zerwas) – Supplemental Appropriations Bill

- Section 25 – HHSC, Mental Health State Hospitals – Appropriated $31,700,000 for mental health state hospital services.

Source: “Texas 86th Legislature Summary of Mental Health and Substance Use-Related Legislation.” Hogg.utexas.edu. 2019. Web. 25 Feb. 2020.

COUNTY AND LOCAL JAILS

Local jails are operated by counties or municipalities and are usually managed by a county sheriff. Jails are the first step after a person becomes involved in the criminal justice system, holding people who are awaiting trial or who have been convicted of low-level crimes. All others held in county jail are awaiting transfer to TDCJ or a state jail facility. According to data provided by the Texas Commission on Jail Standards (TCJS), 87 percent of people charged with felonies and 83 percent of people charged with misdemeanors that are currently in jail had yet to be convicted.

TCJS is the regulatory agency for local jails. As of February 25, 2020, there were 239 facilities under its purview, including seven privately operated facilities and three privately operated state jails. TCJS is tasked with assisting local governments in providing safe and constitutional conditions of confinement for individuals who are detained across Texas, including setting jail standards and inspecting county jail facilities. However, TCJS does not provide oversight within city-operated municipal jails; municipal jails in Texas are not regulated by any external agencies.

TDCJ RESPONSIBILITIES AND MISSION

TDCJ operates state jails facilities and prisons. These facilities hold individuals who have been convicted of an offense. TDCJ operates these facilities and oversees contracts with private correctional agencies. A major distinction between county jails and juvenile facilities is that the Texas prison and state jail system is monitored by its own oversight department – the TDCJ Ombudsman Program. In recent years, legislators and advocacy groups have argued the need for effective, independent oversight of the state jail and prison system.

TDCJ’s mission is to “provide public safety, promote positive change in offender behavior, reintegrate offenders into society, and assist victims of crime.” In addition to in-prison management, the department also manages people who are in the community on parole. TDCJ is responsible for providing health services, including mental health and substance use services, to people who are convicted and sentenced to state jails, state prisons, and private correctional facilities that contract with TDCJ. The Correctional Managed Health Care Committee must develop statewide policies regarding correctional health care services and coordinate the delivery of those services to persons in the TDCJ system. The committee is made up of nine voting members, including a TDCJ representative, medical doctors, and mental health professionals, as well as one non-voting member who is appointed by the Texas Medicaid director.

Funding

On January 31, 2020, there were 144,593 individuals incarcerated in Texas prisons, which accounted for over 97 percent of TDCJ’s operating capacity. The average cost of incarcerating an individual in a state facility was $62.34 per day in 2018. In contrast, individuals on parole cost was $4.39 per day, and individuals on community supervision cost was $3.75 per day.

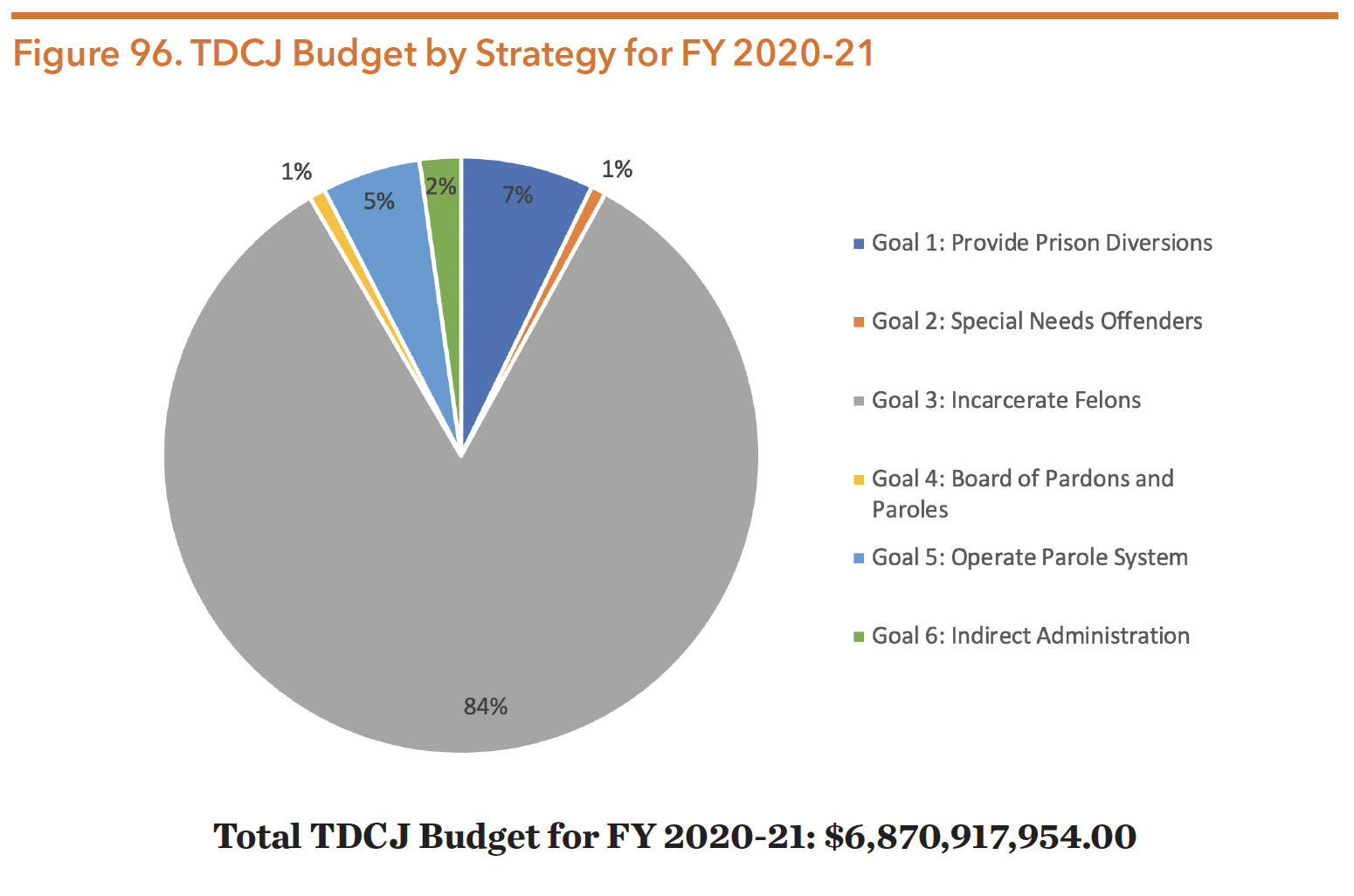

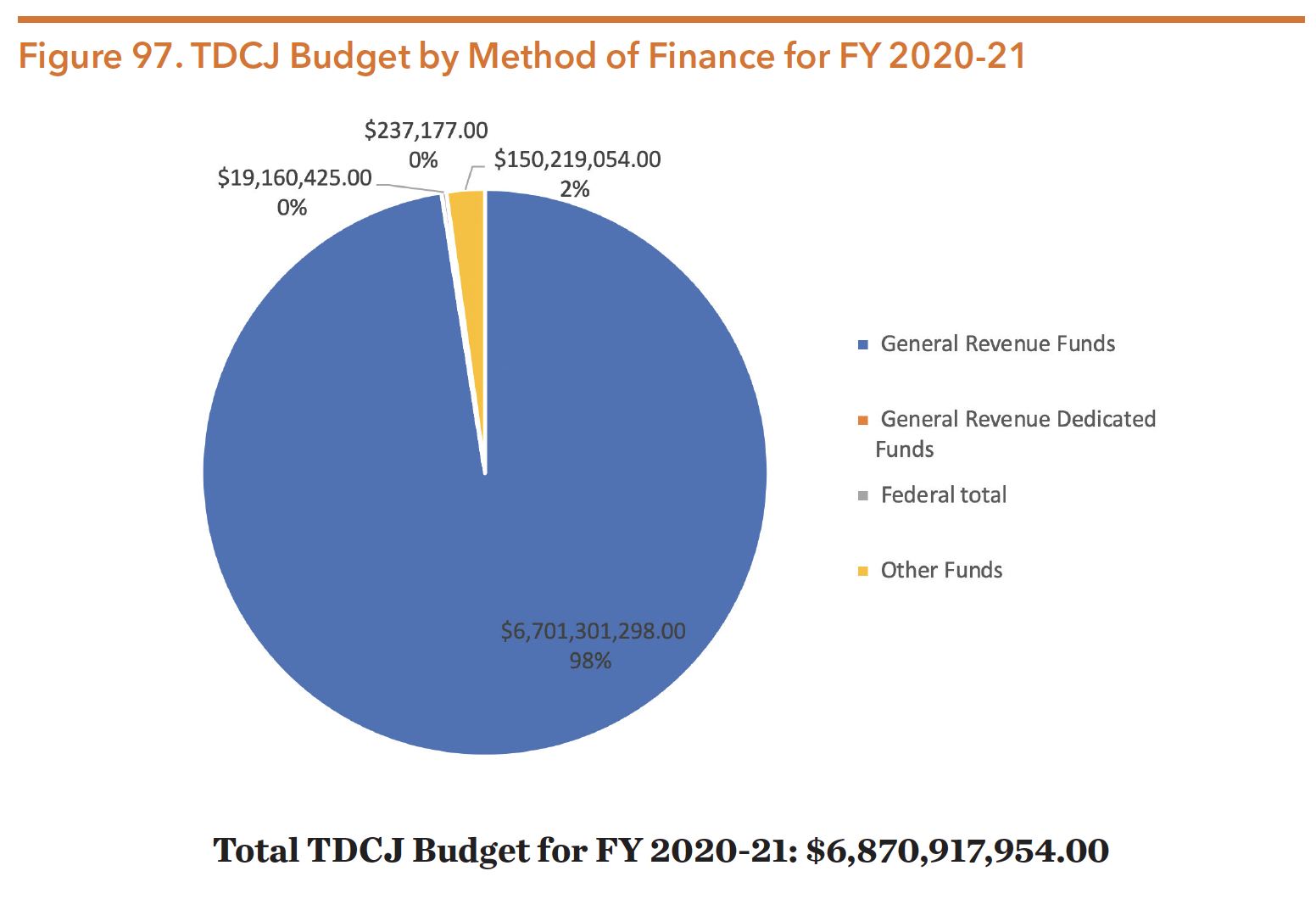

The TDCJ budget for FY 2020-21 was about $6.871 billion, with 6.7 billion (about 98 percent) of revenue coming from general revenue. Only a small portion of the TDCJ budget came from federal funding. With regards to agency goals, about 84 percent was allocated for incarceration. By contrast, seven percent was provided for diversion, five percent for operating parole systems, two percent for indirect administration, one percent for board of pardons and paroles, and one percent for special needs offenders.

The Special Needs Offender Program (SNOP) includes the Substance Abuse Felony Punishment Facilities (SAFPF) and In-Prison Therapeutic Communities (IPTC) for those with special needs inside of prisons. It also includes mentally impaired (MI), intellectual/developmental disabilities (IDD), terminally ill (TI), physically handicapped (PH), and medically recommended intensive supervision (MRIS) offenders on parole.

Source: Zerwas & Nelson. (2019). H.B. No. 1 General Appropriations Act Eighty-Sixth Legislature. Retrieved from https://capitol.texas.gov/BillLookup/History.aspx?LegSess=86R&Bill=HB1

Source: Zerwas & Nelson. (2019). H.B. No. 1 General Appropriations Act Eighty-Sixth Legislature. Retrieved from https://capitol.texas.gov/BillLookup/History.aspx?LegSess=86R&Bill=HB1

TDCJ Facilities and Housing Classifications

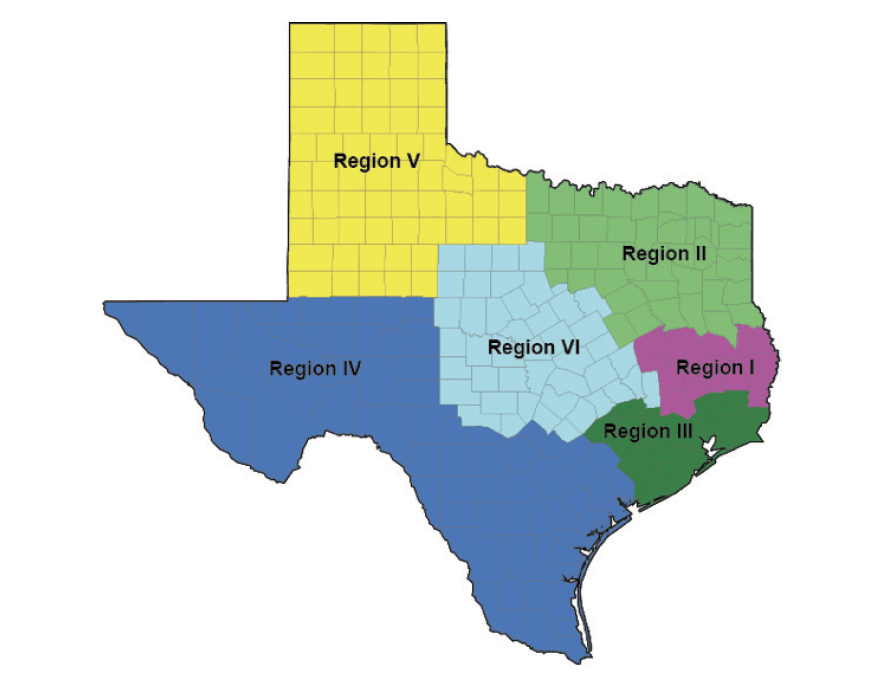

TDCJ has facilities located throughout the state in six regions, with headquarters in both Austin and Huntsville. Each of the TDCJ Institutional Division regions has an administrative director. Regions are pictured below.

Map Source: “Unit Directory – Region/Type Of Facility/Map.” Tdcj.texas.gov. https://www.tdcj.texas.gov/unit_directory/unit_map.html

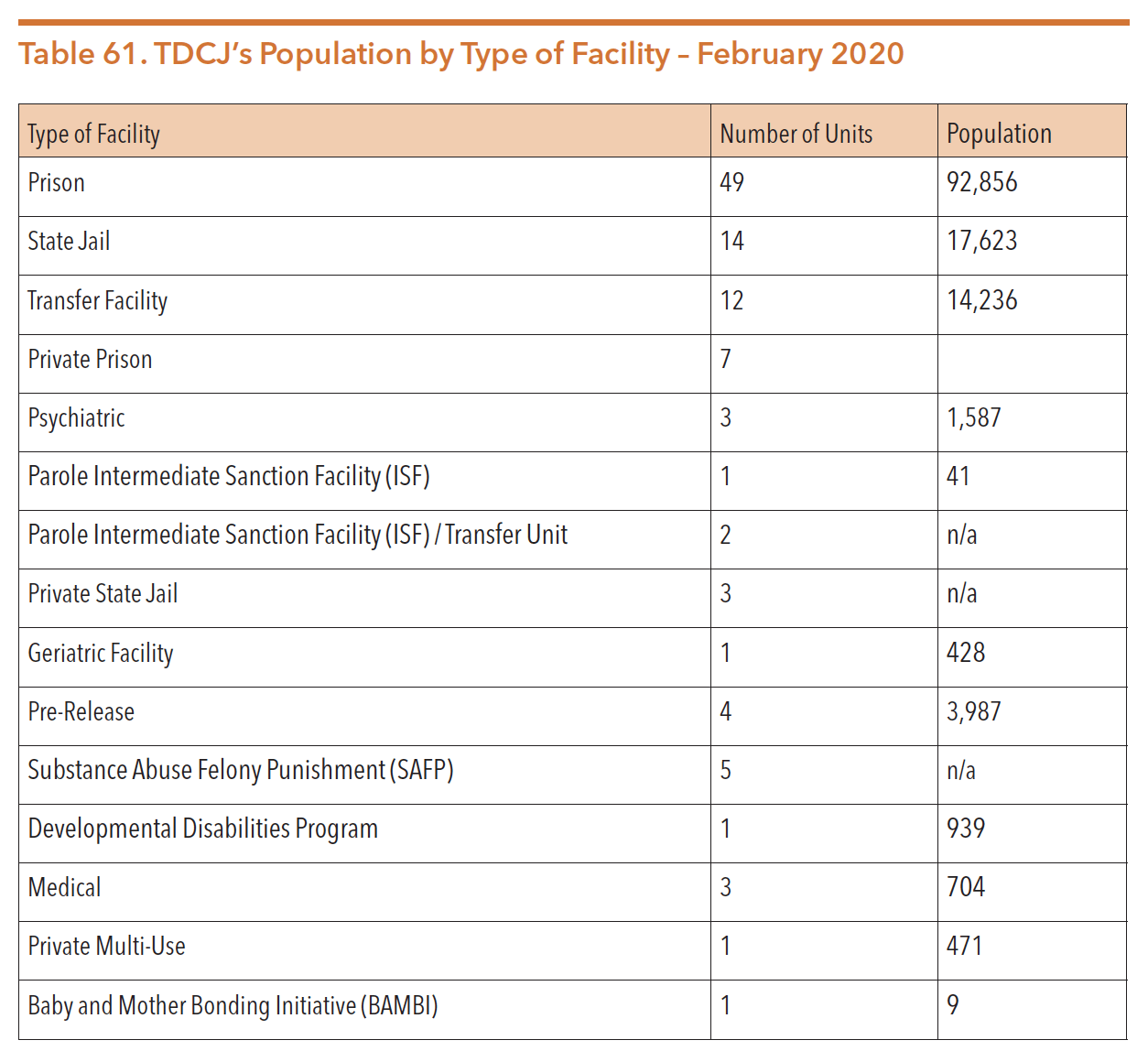

The Texas criminal justice system classifies and houses individuals based on level of felony, medical or mental health need, or programmatic need. The table below depicts TDCJ’s population distribution by facility of facility.

Sources: “Unit Directory – Region/Type Of Facility/Map.” Tdcj.texas.gov. https://www.tdcj.texas.gov/unit_directory/unit_map.html

“Prison Units | Texas Prison Inmates | The Texas Tribune.” The Texas Tribune. https://www.texastribune.org/library/data/texas-prisons/units/. Data Accessed 27 Feb. 2020.

State Jails

While all states have prisons, Texas has an unusual “state jail” category. The state jail felony system was created in 1993 by legislators seeking to address prison overcrowding by creating an alternative for people convicted of low-level, non-violent offenses. State jails were intended to provide a brief term of confinement as a part of community corrections, with a focus on rehabilitation. TDCJ was mandated to create work, rehabilitation, education, and recreational programming on a 90-day cycle, the intended maximum normal term for those committed to state jails. Yet the framework was dependent on courts’ commitment to keep people convicted of state jail felonies on the docket for the entirety of their sentence, so that judges could continue to supervise defendants upon release back to the community. Judges widely rejected this model and preferred to sentence defendants to determinate sentences in state jails with no post-release supervision. Moreover, the legislature never funded the rehabilitation-focused programming inside state jail, which resulted in people released from state jail to the community without rehabilitative programming. Consequently, people released from state jails have worse recidivism rates than those released from prison. In FY 2018, only 84 of the 16,941 people leaving state jail were under community supervision (0.4 percent). A three-year re-arrest, reconviction, and re-adjudication finding by the LBB found rates significantly higher for people leaving state jails (63.1 percent) compared to prison (46.3 percent).

While “state jail” is a placement category, there are no separate facilities for state jails. In 2003, TDCJ’s State Jail Division merged into the Correctional Institutions Division. The facilities are considered “transfer facilities.” People convicted of state jail felonies are in a separate dormitory, but the transfer facilities also house people convicted of more serious felonies who are in “transfer” status for up to two years waiting for a bed in a state prison unit.

A complete list of facilities by region is available at http://www.tdcj.state.tx.us/unit_directory/unit_map.html.

Solitary Confinement and Mental Health

Justice-involved people who have spent time in solitary confinement (administrative segregation) are at a greater risk for lifelong mental health impacts and well-being compared to those in standard housing and classification designations. Individuals in solitary are up to eight times more likely than those in the general prison population to engage in self-harm and nine times more likely to die by suicide. On September 1, 2017, TDCJ changed their policy on solitary confinement, eliminating it as a punishment. As a result of the policy change, people held in administrative segregation dropped from 7,200 in August 2013 to less than 4,000 in July 2017. Despite changes in policy, TDCJ still houses a large number in solitary confinement due to gang affiliations, high escape risk, death sentence, or ongoing danger to staff or other prisoners. People with mental health conditions are overrepresented in solitary confinement usage. In 2014, about 30 percent of TDCJ’s isolated population was identified as having some form of mental illness treatable by outpatient care.

A 2019 report found that individuals who volunteered for a mental health diversion program said promises of therapy and time out of their cells were not fulfilled. While TDCJ created a mental health therapeutic diversion program (MHTDP) with group counseling, individual counseling, and self-study programs, the program has proven to be a disappointment to people in custody. Individuals in the program report that it operates much like solitary confinement in that they are held in isolation almost continuously without intended services. Alarmingly, MHTDP participants are not included in the official count of prisoners held in solitary even though they are held in similar conditions.

Depending on the circumstances, TDCJ utilizes two types of solitary confinement for varying lengths of time. Historically, correctional officers used short-term disciplinary segregation for punitive purposes. This option was eliminated in September 2017; the ban required a change in placement for 76 people. Then TDJC shifted its use of administrative segregation to house people for an indefinite period of time when they are considered dangerous to themselves or others, holding individuals in a small, isolated cell for about 22 hours per day. Administrative segregation is still common within TDCJ. In September 2017, roughly 4,000 people were in administrative segregation. On average, TDCJ inmates remain in isolation for almost four years. However, in 2015, ten individuals in TDCJ custody reached 30 consecutive years in administrative segregation. Individuals kept in solitary confinement for even short spans of time can experience negative mental health outcomes, including major depression, cognitive disturbances, psychosis, and suicidal ideation.

Despite the adverse mental health outcomes of individuals held in solitary confinement, until recently individuals were frequently released directly from administrative segregation into the community. Referred to as a “flat release,” this practice occurs when incarcerated individuals finish their prison sentences while they are housed in administrative segregation. TDCJ must then release them directly from the most restrictive prison environment (i.e., isolation) to the streets without any supervision or support. Research shows that flat release is linked to higher recidivism rates, which places both formerly justice-involved individuals and their fellow community members at risk. By the end of 2016, TDCJ no longer released people directly from administrative segregation into the community. Instead, the agency requires individuals housed in administrative segregation to complete a pre-release program that has three phases: motivational interviewing, cognitive change programming, and reentry planning in effort to reduce negative outcomes.

Assault and the Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) Investigations

Traumatic experiences such as sexual assault can impact the mental health of people incarcerated in the general prison population. In effort to protect an individual who has experienced a sexual assault, prison officials will oftentimes place a sexual assault victim in solitary or protective custody.

A 2013 survey by the Bureau of Justice Statistics ranked the U.S. prisons with the highest sexual assault complaints reported by people confined in prisons; 25 percent were located in Texas (an improvement over the 2008 survey in which Texas was home to 50 percent of those prisons). People with mental illness are at a higher risk of sexual assault. One survey showed that 6.3 percent of people in prison identified with “serious psychological distress” reported sexual victimization by another person under confinement, in contrast to reported victimization by 0.6 percent of people without a mental health condition.

The Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA), a federal law passed in 2003, intended to institute a zero-tolerance policy for prison rape in correctional settings. The Texas PREA Ombudsman is responsible for ensuring that TDCJ follows federal regulations created to eliminate sexual assaults in prison facilities. The position investigates inmate-on-inmate sexual abuse reports, as well as staff-on-inmate sexual abuse and harassment. In 2016, the PREA Ombudsman office found 43 percent of incidents reported met the elements of the Texas Penal Code for Sexual Assault or Aggravated Sexual Assault.

Jails are also required to comply with PREA requirements, with oversight provided by the Texas Commission on Jail Standards as part of its general oversight duties.

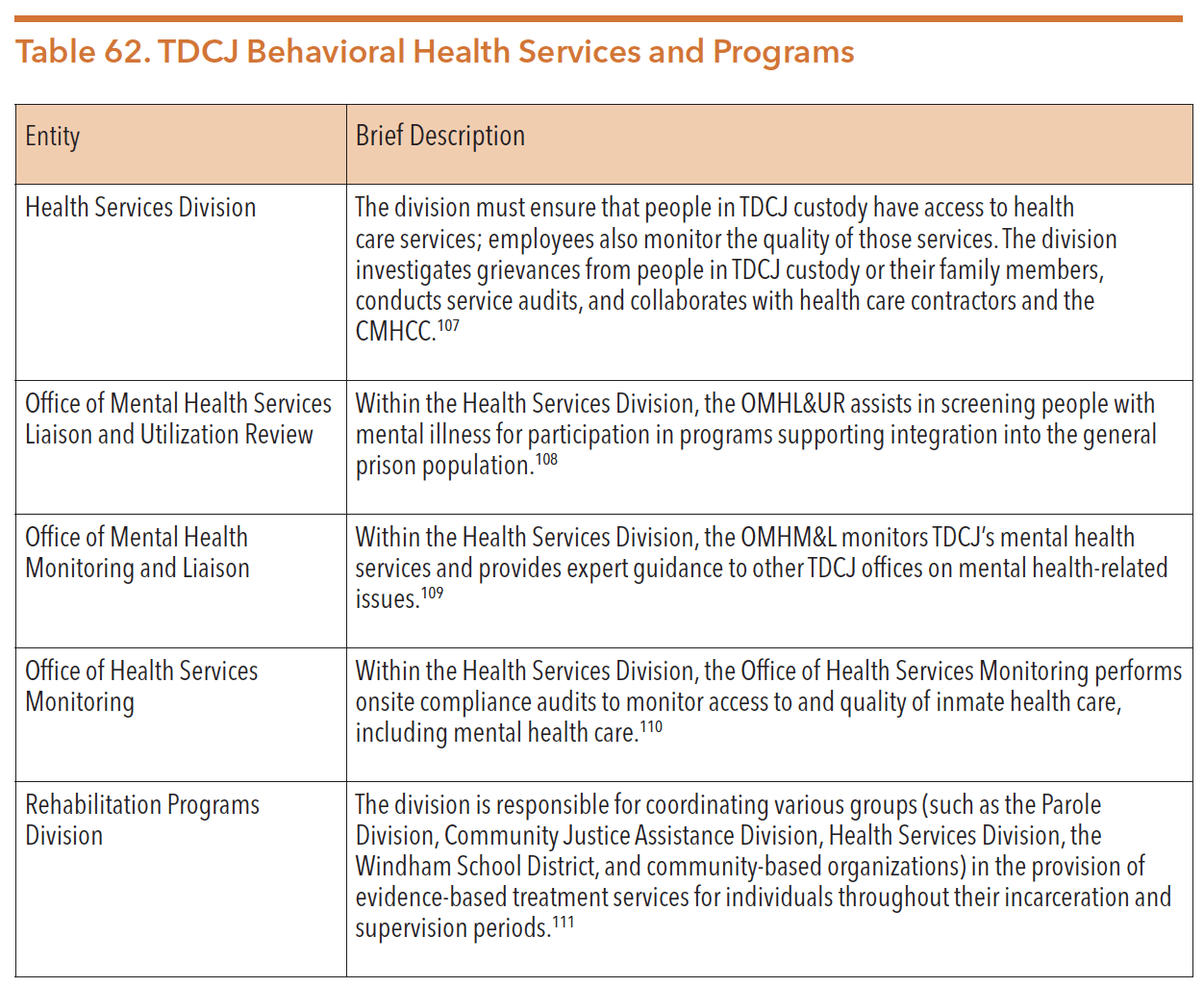

TDCJ Behavioral Health Services and Programs

TDCJ is comprised of subdivisions that manage and operate the agency, supervise incarcerated individuals, and provide services to crime victims. Within TDCJ, there are several offices and agencies responsible for meeting the physical and behavioral health needs of people confined in prisons. The table below provides a brief description of each office or agency.

ACCESS TO SERVICES

The Correctional Managed Health Care Committee developed the Offender Health Services Plan, which provides two levels of health care services to incarcerated individuals within TDCJ. The plan prioritizes two classification levels of health services for medical, dental, and mental health needs.

Level I – Medically Mandatory care is that which is essential to life and health and without which rapid deterioration is expected. The recommended treatment intervention is expected to make a significant difference or be very cost effective. This level of care is available to all individuals incarcerated.

Level II – Medically Necessary care is that which is not immediately life threatening, but without which the patient could not be maintained without significant risk of serious deterioration, or where there is a significant reduction in the possibility of repair later without treatment. Level II care may be provided to all individuals incarcerated, but evolving standards and practice guidelines control the extent of service.

Each TDCJ facility must develop a process by which individuals who are incarcerated can gain access to medical, mental health, substance use, and dental care. This process is commonly referred to as “sick call.” At intake, incarcerated persons are provided information on how to obtain health care services within their assigned facility. Facilities may identify people with mental health conditions during the intake process or upon referrals from security staff who receive mental health-related training.

In addition to the Correctional Managed Health Care Committee, the TDCJ parole board also plays a significant role in individuals gaining access to health services. The Medically Recommended Intensive Supervision (MRIS) Program identifies offenders who are elderly, physically handicapped, mentally ill, terminally ill, or have a condition requiring long term care for early release on parole. Referrals are screened by TCOOMMI and must meet certain criteria for eligibility. Offenders having a sentence of death or sexual offense are not eligible.

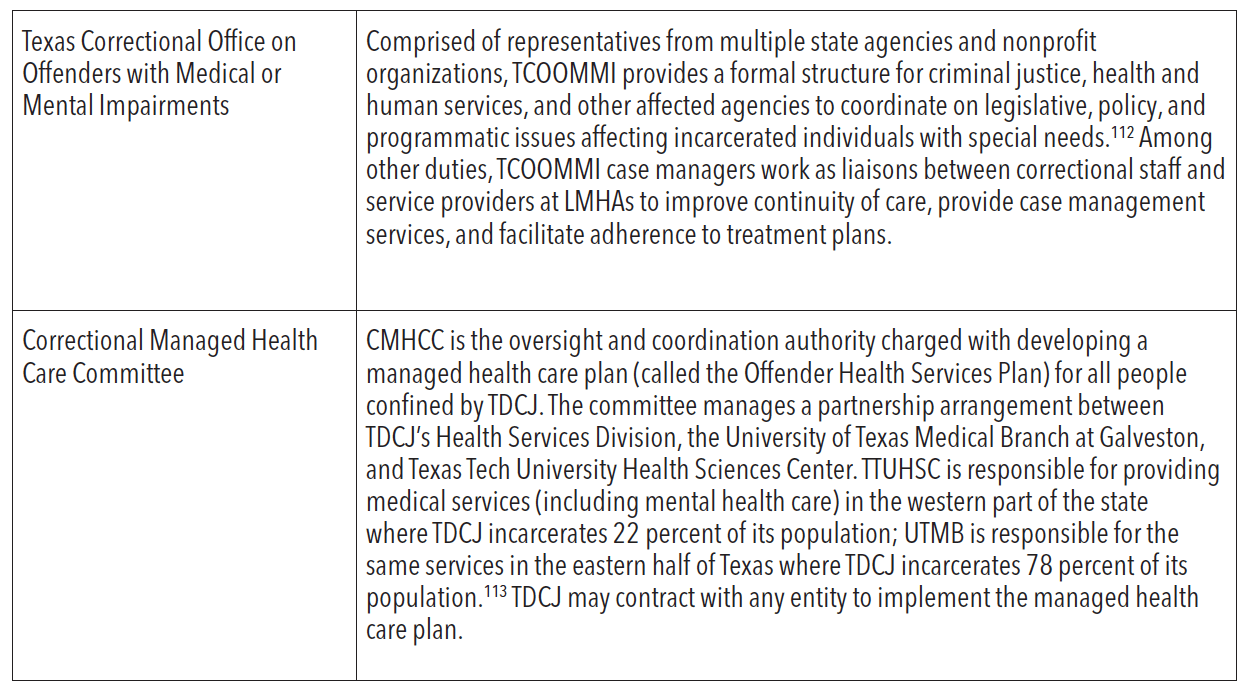

MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES

Qualified mental health providers may recommend the following mental health diagnostic and treatment services for people in TDCJ custody with behavioral health needs:

- Emergency mental health crisis services (available 24 hours a day, seven days per week)

- Professional medical services such as medication management and monitoring

- Continuity of care services

- Psychosocial services including talk therapy

- Crisis management/suicide prevention

- Inpatient services provided by a correctional health care approved facility, including diagnostic evaluation, acute care, transitional care, and extended care

- Outpatient services

- Specialized programs

The table below describes these programs.

* Note: TDCJ classifies individuals housed in state prisons into six custody levels, ranging from the least restrictive to the most restrictive. These levels include: G1 (General Population Level 1), G2, G3, G4, G5, and Administrative Segregation. Individuals with a G4 security status are housed in cells rather than dorms, and they may not work outside the security fence without armed supervision. Individuals with a G5 security status who have histories of assaultive or aggressive behavior are housed in cells and may not work outside the security fence without armed supervision.

Source: Correctional Managed Health Care Committee. (September 2015). Correctional Managed Health Care Policy Manual. https://www.tdcj.texas.gov/divisions/cmhc/docs/cmhc_policy_manual/A-08.03.pdf. Accessed 14 Apr. 2020.

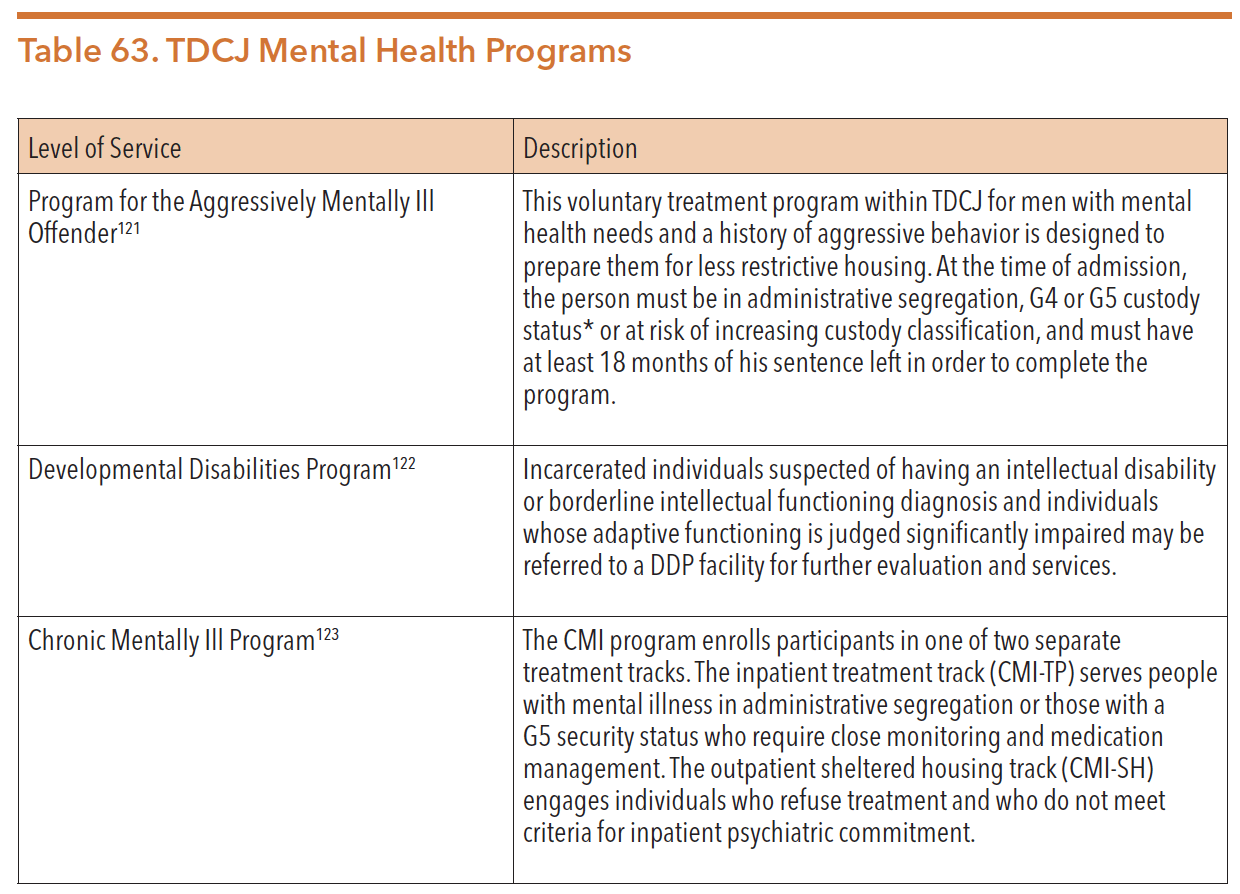

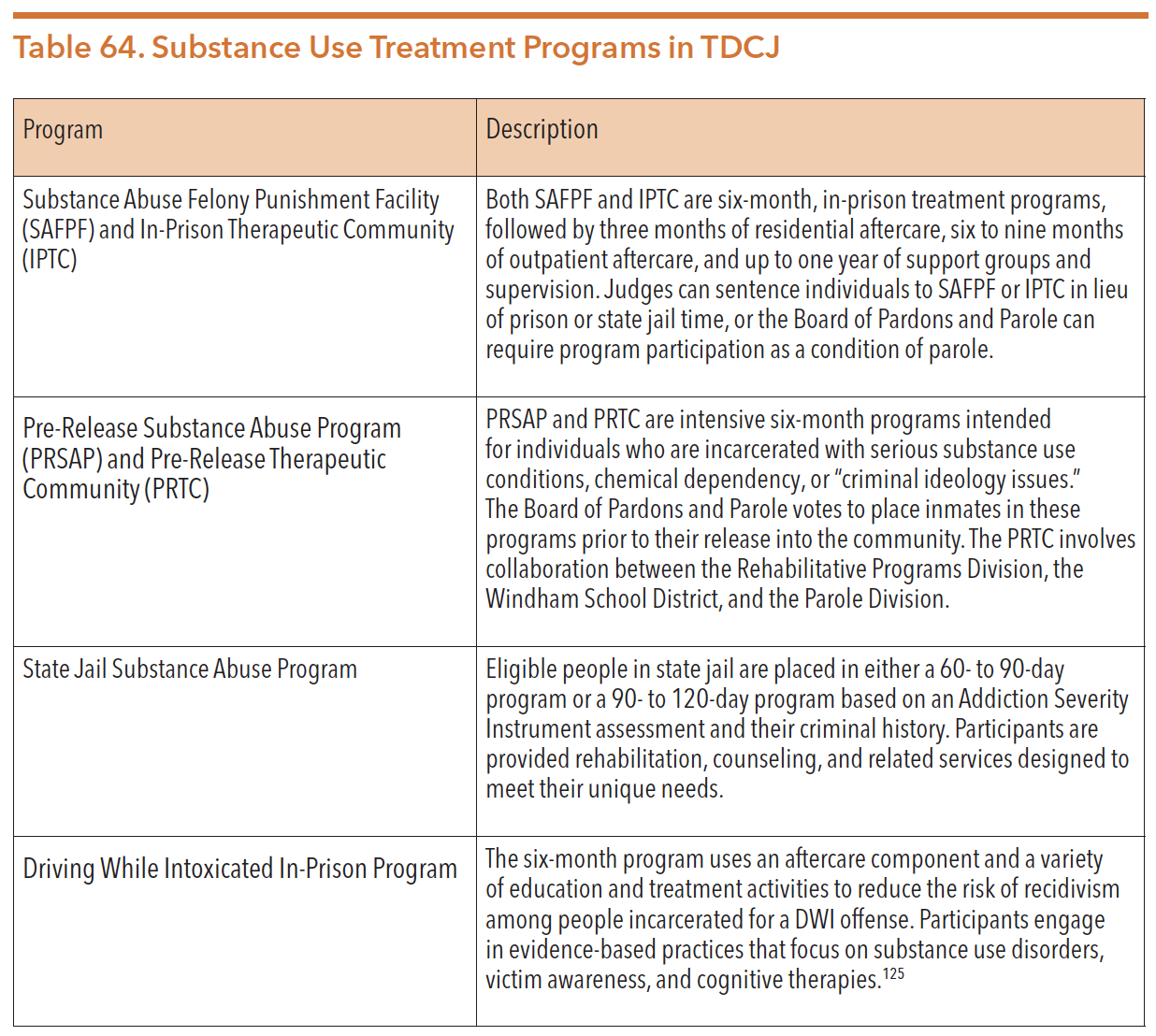

SUBSTANCE USE TREATMENT SERVICES

An April 2018 report revealed that 70 percent of women and 58 percent of men within TDCJ were diagnosed with a substance use disorder. In addition to mental health programs, TDCJ also manages a number of programs within its Rehabilitation Programs Division to serve people with substance use conditions. The table below describes these programs.

Source: Texas Department of Criminal Justice. (n.d.). Rehabilitation Programs Division. https://www.tdcj.texas.gov/divisions/rpd/substance_abuse.html. Accessed June 2020.

POST-INCARCERATION COMMUNITY-BASED SERVICES

Recidivism into the criminal justice system is a key concern for all people returning to the community after a period of incarceration. In the three years after leaving TDCJ custody, re-arrest rates range from 46 percent of people released from prison to 63 percent of people released from state jail. Additionally, reincarceration rates are 21 percent of people released from prison and 32 percent of people released from state jail. TDCJ operates several programs aimed at supporting reentry into the community and reducing recidivism rates.

TEXAS CORRECTIONAL OFFICE ON OFFENDERS WITH MEDICAL OR MENTAL IMPAIRMENTS (TCOOMI)

Within TDCJ’s Reentry and Integration Division, the Texas Correctional Office on Offenders with Medical or Mental Impairments (TCOOMI) program provides a variety of institutional and community-based services to facilitate the reentry of people with special needs back into the community. TCOOMMI partners with LMHAs to provide three types of reentry services for people with mental illness: continuity of care, case management, and medically recommended intensive supervision. In recent years, TCOOMMI has expanded eligibility to include all people with serious and persistent mental illness. In FY 2016, TCOOMMI provided continuity of care services to 35,305 individuals.

Upon their release from incarceration, TCOOMMI refers clients to LMHAs for services, such as case management, psychological and psychiatric services, medication and monitoring, and benefit eligibility services (including federal entitlement application processing). In FY 2017, TCOOMMI worked with LMHAs to provide 26,367 justice-involved individuals with community-based behavioral health services.

Efforts to reduce recidivism involve linking justice-involved individuals to community services and supports to help address the root causes underlying a person’s previous criminal behavior. This is done to prevent reentry into the criminal justice system. In 2013, TCOOMMI implemented the Risk Needs Responsivity model to reduce recidivism among high-risk individuals utilizing TCOOMMI case management services. In 2015, the three-year recidivism rate was 12.4 percent for clients with high risk and clinical needs who were served for at least one year in TCOOMMI case management programs, while TDCJ’s general recidivism rate was 21.4 percent. In FY 2017, TCOOMMI provided case management services to 7,507 individuals.

TCOOMI is also involved with the Medical Recommended Intensive Supervision, described in the section on Access to Services Level II. The purpose of the program is to release individuals who pose minimal public safety risk back into the community in order to improve individual health outcomes and cut costs. If an individual is approved for early MRIS release, TCOOMMI specialists will expedite the release planning process and facilitate reentry case management. In FY 2016, 86 people in prison and 9 people in state jail were approved for MRIS release.

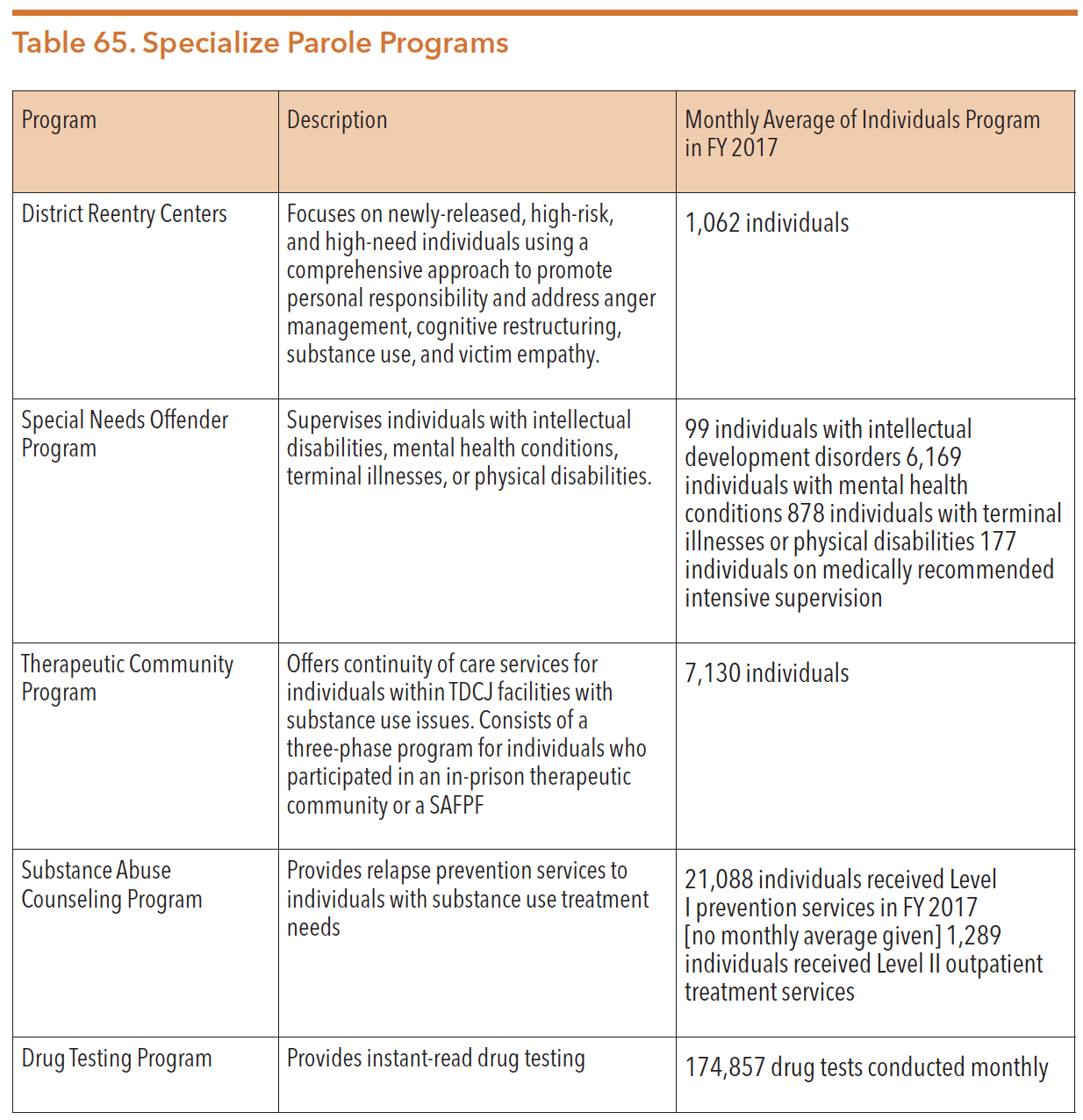

SPECIALIZED PAROLE PROGRAMS

While the MRIS program provides services to some persons with serious mental illness leaving TDCJ custody, other specialized programs may be available for individuals with mental health and substance use issues who are released from incarceration. The table below provides an overview of the most relevant programs.

Source: Texas Department of Criminal Justice. (n.d.). Annual Review 2017. Page 30. https://www.tdcj.texas.gov/documents/Annual_Review_2017.pdf. Accessed 7 Mar. 2020.

Reentry Services

TDCJ’s Reentry and Integration Division provides both pre-release and post-release programs statewide. As of September 2018, it had 128 pre-release, 8 release-dedicated, and 51 post-release case managers. Case managers can be located in correctional facilities, district parole offices, or community residential facilities (halfway houses). The remaining 10 positions were dedicated to serving the special needs offender population.

Returning to the community after time in a TDCJ facility is a challenging aspect of an individual’s criminal justice involvement. Reentry is the reintegration back into society from jail or prison. It involves skillful planning and patience, in addition to the dual commitment from the individual and the community to achieve overall wellness. The process of reintegrating back into the community impacts many parts of a person’s health and well-being, including mental health continuity of care.

Reentry programs are available in local communities through governmental, faith-based, non-profit, and for-profit programs. These programs fall into two categories: general reentry and residential reentry. Cities currently listed in Texas* with local reentry programs include:

- Austin

- Azle

- Beaumont

- Brownsville

- Dallas

- Del Valle

- Edinburg

- Fort Worth

- Houston

- San Antonio

*Note: ReEntry Progams, a service located in Washington DC, keeps its website open for new submissions from visitors to the site.

In 2018, TDCJ launched “Website for Work,” a program to match parolees with employers, arrange for the parolee to contact the employer, and record data on the outcomes of individual members in the program. Website for Work will produce statistical reports on the overall success of the program in helping offenders obtain employment and serve the entire state of Texas, including employers who hire an ex-offender within a year of their release from prison. The employer will also qualify for the federal Work Opportunity Tax Credit (WOTC).

INCARCERATION PREVENTION AND DIVERSION PROGRAMS

Increased demand for mental health services within state prisons and county jails has pushed stakeholders to develop opportunities for diversion from incarceration for people with mental health and substance use disorders. For example, LMHAs provide community-based interventions that can prevent criminal justice involvement. TCOOMMI within TDCJ also collaborates with some of the 39 LMHAs to provide multi-service alternatives to incarceration for justice-involved individuals with special needs. For more information, see the “Texas Correctional Office on Offenders with Medical or Mental Impairments (TCOOMMI)” section of this chapter.

TDCJ awards grant funding to county stakeholders in order to pursue the first goal outlined in its 2017-21 strategic plan: “to provide diversions to traditional incarceration.” The aim of these prevention and diversion programs is to use cost effective, safe, and clinically appropriate strategies that curb the over-incarceration of people with mental illness (among others) charged with low-level crimes.

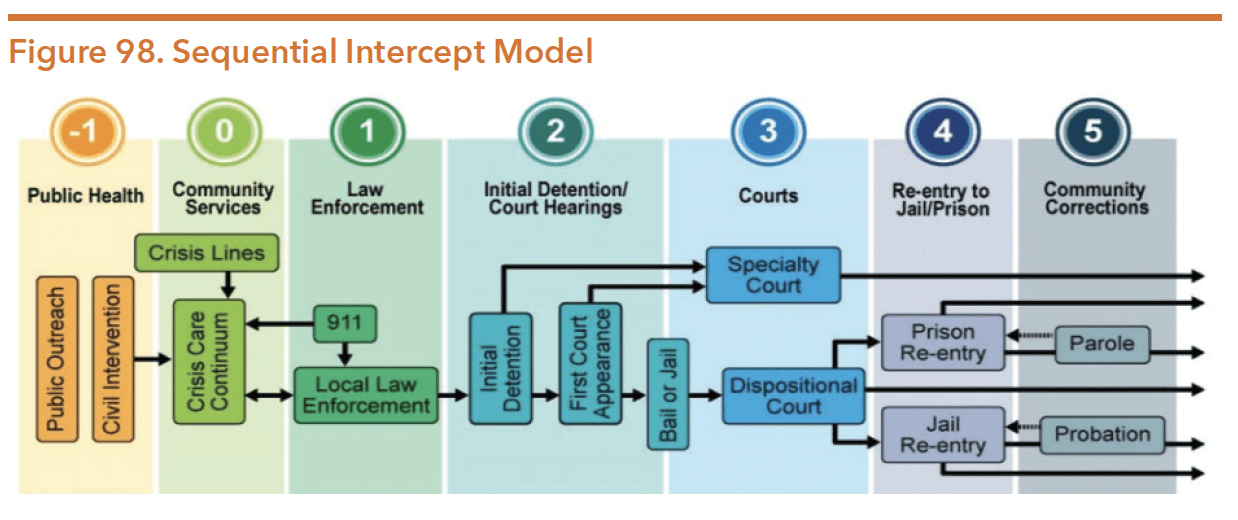

Sequential Intercept Model

The Sequential Intercept Model (SIM) was developed as an informative model for multi-system responses to people with mental health or co-occurring substance use disorders involved in the criminal justice system. Since its development in the early 2000s, the SIM has been widely accepted nationally as well as in Texas. Within the model, there are multiple touchpoints for a person with a mental health condition to engage prior to entering into the criminal justice system, within the criminal justice system, and reintegrating back into the community. The SIM helps connect people with mental health conditions to the right care.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) promotes the SIM as a way to organize prison and jail diversion strategies. The model was developed in conjunction with the GAINS Center and emphasizes “intercept points” at which individuals may be diverted from the justice system. After feedback from communities including some in Texas, the GAINS Center added an Intercept 0. The JCHM also added an Intercept -1, designating public health as the first setting that an individual with a mental illness or IDD should be identified and served prior to criminal justice involvement. The intercept points include:

- Intercept -1: Public health, public outreach, and civil intervention

- Intercept 0: Community services;

- Intercept 1: Law enforcement and emergency services;

- Intercept 2: Initial detention and court hearings;

- Intercept 3: Jails and courts;

- Intercept 4: Reentry into the community; and

- Intercept 5: Community corrections and support services.

Figure 98 below illustrates the key intercept points where people with mental health conditions encounter the criminal justice system.

Source: National Center for State Courts and Arizona Sup. (n.d.). Assessing the Mental Health and IDD Landscape by Intercept. Retrieved from http://texasjcmh.gov/media/1436/assessing-the-mental-health-and-idd-landscape-by-intercept.pdf.

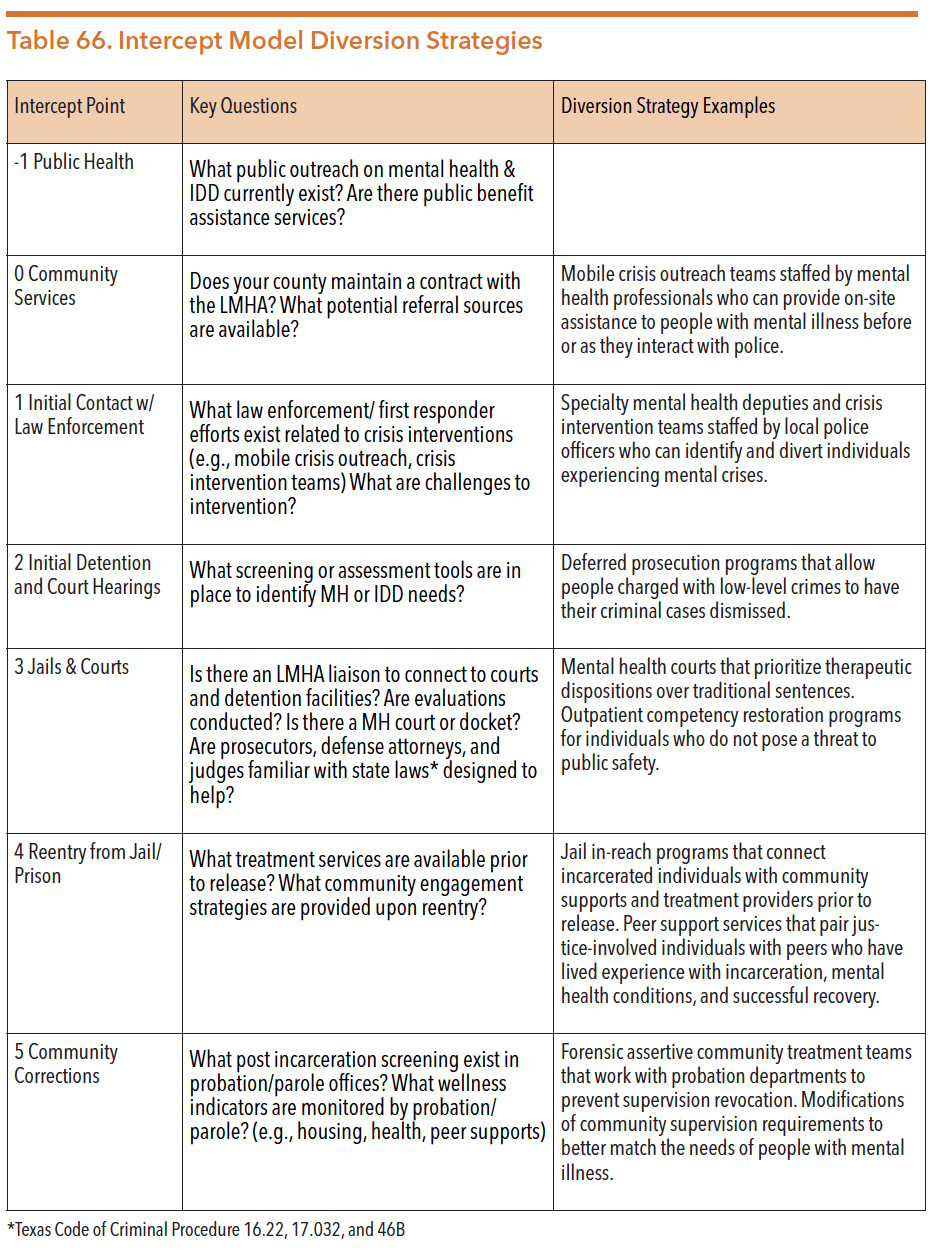

The table below gives some examples of important questions to be asked along with diversion strategies in each intercept point.

Sources: “Assessing The Mental Health And IDD Landscape By Intercept..” Texasjcmh.gov. http://texasjcmh.gov/media/1436/assessing-the-mental-health-and-idd-landscape-by-intercept.pdf. 19 Mar. 2020.

Frost, L. (2016, January 22). Mental Health Diversion from Jail. University of Houston Law Center Police, Jails, and Vulnerable People Symposium. [Updated by the author on September 22, 2018 to include Intercept 0.] See Dr. Frost’s presentation at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LRgNJh2aZuY&index=2&list=PLu2WuYWXjUtcxvWsUGuF3KXhTuUJZ2c1t

Community Examples of Jail Diversion Strategies

At each step of the criminal justice process, the SIM encourages collaboration between LMHAs, law enforcement agencies, and the court system. Collaboration among key stakeholders helps to ensure that people with mental health conditions who commit minor offenses are linked to community-based and recovery-oriented services, supports, and treatment as soon as possible. Research shows that jail diversion efforts can then improve mental health outcomes, save money, and increase public safety.

Section 533.108 of the Texas Health and Safety Code permits LMHAs to prioritize funds for the creation of collaborative jail diversion programs with law enforcement, judicial systems, and local personnel. The type of programs available to persons with mental illness varies from county to county. Some communities, like Bexar and Harris counties (described below), offer robust diversion opportunities that address multiple intercepts of the SIM. Other counties do not have the resources to implement any type of diversion strategy at all. As a result, only a small fraction of Texans with mental illness who are eligible for diversion programming receive any diversion services.

BEXAR COUNTY JAIL DIVERSION PROGRAM

In 2003, Bexar County implemented a jail diversion program that is now viewed as a national service model. Bexar’s diversion initiative was created by the Center for Health Care Services using diverse funding sources including private donations; city, county, and state dollars; and federal block grants. The program employs both pre-booking and post-booking diversion methods. First, Bexar County uses a 24/7 crisis center to provide county residents with immediate intervention when they are experiencing a mental health crisis. Then, MCOTs and CITs work to divert individuals with mental health conditions away from jail settings before they are arrested and booked in a local jail. After booking, the diversion program identifies people with mental illness already in the system and recommends appropriate alternatives to jail, such as court supervised community treatments or mental health bonds. The county created two centers: The Restoration Center for integrated substance use and mental health services and The Crisis Care Center for 24-hour psychiatric emergency care. Finally, Bexar County offers programs that provide continuity of care and housing services for people in need of assistance who are released from incarceration into the community, such as Haven for Hope.

Since its implementation, the combination of Bexar County’s jail diversion strategies and decreased crime rates resulted in a significantly reduced county jail population. In 2003, the jail population exceeded the jail’s capacity by nearly 1,000 people, but by 2015, the county was decommissioning a privately-operated detention center in order to better use 1,000 empty beds at the Bexar County Jail. The program diverts about 26,000 people a year, saving an estimated $10 million annually in jail and emergency department costs.153 Mental health-related trainings also helped to decrease the use of physical force by Bexar County law enforcement officers against people with mental illness. A 2016 report found that the program decreased use of physical force from approximately 50 times a year to 3 times total within two years of beginning operation.

HARRIS COUNTY MENTAL HEALTH JAIL DIVERSION PROGRAM

Harris County, which is home to the fourth largest jail in the nation, created a significant jail diversion program. In 2013, state legislators passed SB 1185 (83rd, Huffman/Schwertner) to create the Harris County Mental Health Jail Diversion Pilot program (MHDJP). The ongoing goal of the program is to promote and sustain recovery for justice-involved individuals with mental health conditions by expanding services for housing, education, supportive employment, and peer advocacy.

In the first few years, the Harris County MHJDP program used two local providers to safely divert people with mental illness away from the criminal justice system. First, the Harris Center for Mental Health and IDD (formerly MHMR of Houston) used a jail-based team, a community and clinic-based team, and critical time intervention case management services to identify people in jail with mental illness. They also initiated pre-release treatments and linked participants to established community support networks. Second, Healthcare for the Homeless-Houston and SEARCH Homeless Services enrolled eligible participants in a Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) program. For more information on PSH, see the TDHCA chapter of this guide.

People can spend a few hours or days at the Harris Center to get treatment and connected to a range of community-based services. At each stage of the diversion program, people with mental health concerns receive access to evidence-based services, including cognitive behavioral therapy, substance use interventions, peer support, permanent supportive housing, and intensive case management. The Judge Ed Emmett Mental Health Diversion Center was opened in 2018, providing a 29-bed resource for pre-jail diversion of people accused of low-level non-violent offenses.

LUBBOCK COUNTY MENTAL HEALTH COLLABORATIONS

Despite being a rural county with a population of less than 300,000 by the 2010 U.S. census, Lubbock County has implemented programs to serve MH and IDD needs during incarceration. In 1997, the Lubbock County Sheriff’s Office and the Lubbock Regional Mental Health Mental Retardation Center developed a Memorandum of Understanding allowing people with severe and persistent mental illness to be treated while in jail. While considering the needs of this population, Lubbock County has continued to ration scarce resources to fund jail operations along with a myriad of other services. Collaborations between StarCare Specialty Health System, the Lubbock County Sheriff’s Department, and the Lubbock Police Department serve people with mental health conditions by diverting them into health care settings rather than jail.

In December 2018, Lubbock police launched its Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) aimed at diverting people with mental illnesses from jail. Team members’ tasks include knowing how to identify mental health conditions, how to de-escalate, how to respond, as well as how to refer people in mental health crises so that they do not get involved in the criminal justice system. The creation of the crisis team has helped police and people in crisis to talk about mental illness, breaking the stigmas of mental health issues.

Specialty Courts

Counties can use specialty courts to divert people with mental health concerns and substance use issues away from jail settings. These courts apply problem-solving techniques to provide community-based alternatives to incarceration. Each type of specialty court requires the collaboration of judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys, law enforcement officers, and mental health professionals. Specialty courts tend to focus on an identified issue (mental illness, substance use), an identified group (veterans, juvenile, family drug), or a specific offense (DWI, prostitution).

As of March 2020, there were approximately 147 adult specialty courts registered in Texas. In FY 2016, the Office of the Governor’s Criminal Justice Division (CJD) allocated $11.6 million in general revenue-dedicated funds for discretionary grants to 89 specialty courts across Texas. In FY 2015, CJD-funded courts served approximately 3,570 participants, 61 percent of whom completed their program successfully.

In 2019, the Texas legislature passed HB 2955 (86th, Price/Zaffirini), a bill that moved specialty courts from the purview of the governor’s office to the Office of Court Administration (OCA).165 Specialty courts must now register with the OCA, which provides technical assistance and monitoring for compliance with programmatic best practices.

As of 2018, there was no statewide data collected on specialty courts. The Criminal Justice Division of the Office of the Governor, which previously had jurisdiction over Texas specialty courts, stated in 2018 that these courts have reduced the number of people with mental illness who are incarcerated in the state.

DRUG COURTS

Drug courts provide more comprehensive and intensive supervision compared to other forms of community supervision. Research shows that the drug court model of supervised treatment, in combination with judicial monitoring, can more effectively reduce drug use and crime compared to either treatment or judicial sanctions outcomes separately. Data shows that this model works; researchers have found that drug court participation can decrease three-year recidivism rates by up to 5 percent. In 2001, the 77th Legislature passed HB 1287 (77th, Thompson/ Whitmire), which mandated all Texas counties with populations exceeding 550,000 to apply for federal and other funds in order to establish drug courts. As of March 2020, there were approximately 147 drug courts in counties throughout Texas. These courts covered: driving while intoxicated (DWI), veteran’s treatment, co-occurring disorder, and hybrid DWI/ drug courts.

FAMILY DRUG COURTS

Family treatment courts, also referred to as family drug courts and dependency drug courts, use a multidisciplinary, collaborative approach to serve families with substance use disorders and who are involved with the child welfare system.

In 2005, the 79th Texas legislature defined family drug court programs as having the following essential characteristics:

- Integration of substance abuse treatment services in the processing of civil cases in the child welfare system;

- Use of a comprehensive case management approach involving Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS) caseworkers, court-appointed case managers, and court-appointed special advocates to rehabilitate a parent who has had a child removed from the parent’s care;

- Early identification and prompt placement of eligible parents who volunteer to participate;

- Comprehensive substance use needs assessment and referral to an appropriate substance use treatment agency;

- Monitoring of abstinence through periodic alcohol or other drug testing;

- Ongoing judicial interaction with program participant monitoring and evaluation of program goals and effectiveness;

- Continuing interdisciplinary education to promote effective program planning, implementation, and operations; and

- Development of partnerships with public agencies and community organizations.

Family drug courts seek to provide safe environments for children, intensive judicial monitoring, and interventions to treat parents’ substance use disorders and other co-occurring risk factors. As of July 2019, there were 14 family drug courts across the state of Texas.

MENTAL HEALTH COURTS

Mental health courts were developed across the country as an alternative to the standard adjudication process for people with mental health conditions who have committed low-level offenses. Like drug courts, mental health courts use non-adversarial, judicially-supervised treatment plans to reduce recidivism that is fueled by untreated mental illness and substance use conditions. As of July 2019, Texas had 18 mental health courts.

VETERANS COURTS

Veterans Court Programs are mental health and drug treatment courts that provide alternatives to traditional criminal prosecution for veterans who meet specific criteria and suffer from a mental health condition, including substance use conditions. The purpose of these programs is to provide treatment for mental health conditions that caused or affected the actions of the veteran in the criminal offense charged.

Veteran courts provide an alternative to criminal prosecution for certain offenses and for the proper medical treatment of veterans who have served our country. Some state veteran programs (e.g., Dallas County Veterans Court), through direct coordination with the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, can help to provide medical treatment, mentoring, and other services to our nation’s veterans who are facing qualifying criminal charges. As of July 2019, there were 30 veterans’ courts throughout Texas.

Mental Health Public Defender Offices

Criminal cases involving people with mental health conditions often present unique legal issues that require specialized knowledge and skills. Jurisdictions that have a public defender office can train attorneys on mental health-related issues in order to better serve clients. However not all counties have a public defender office. Thus, some areas without designated countywide public defenders have established a Mental Health Public Defender office that specializes in addressing the legal needs of people with mental illness who are charged with crimes.

As of 2017, there were 12 mental health defender programs in Texas: 9 public defender offices with a mental health division or specialization and 3 managed assigned counsel (MAC) programs. Public defender offices are those which the attorney is an employee of the office, whereas MAC office attorneys who represent indigent clients are contractors rather than employees of the office.

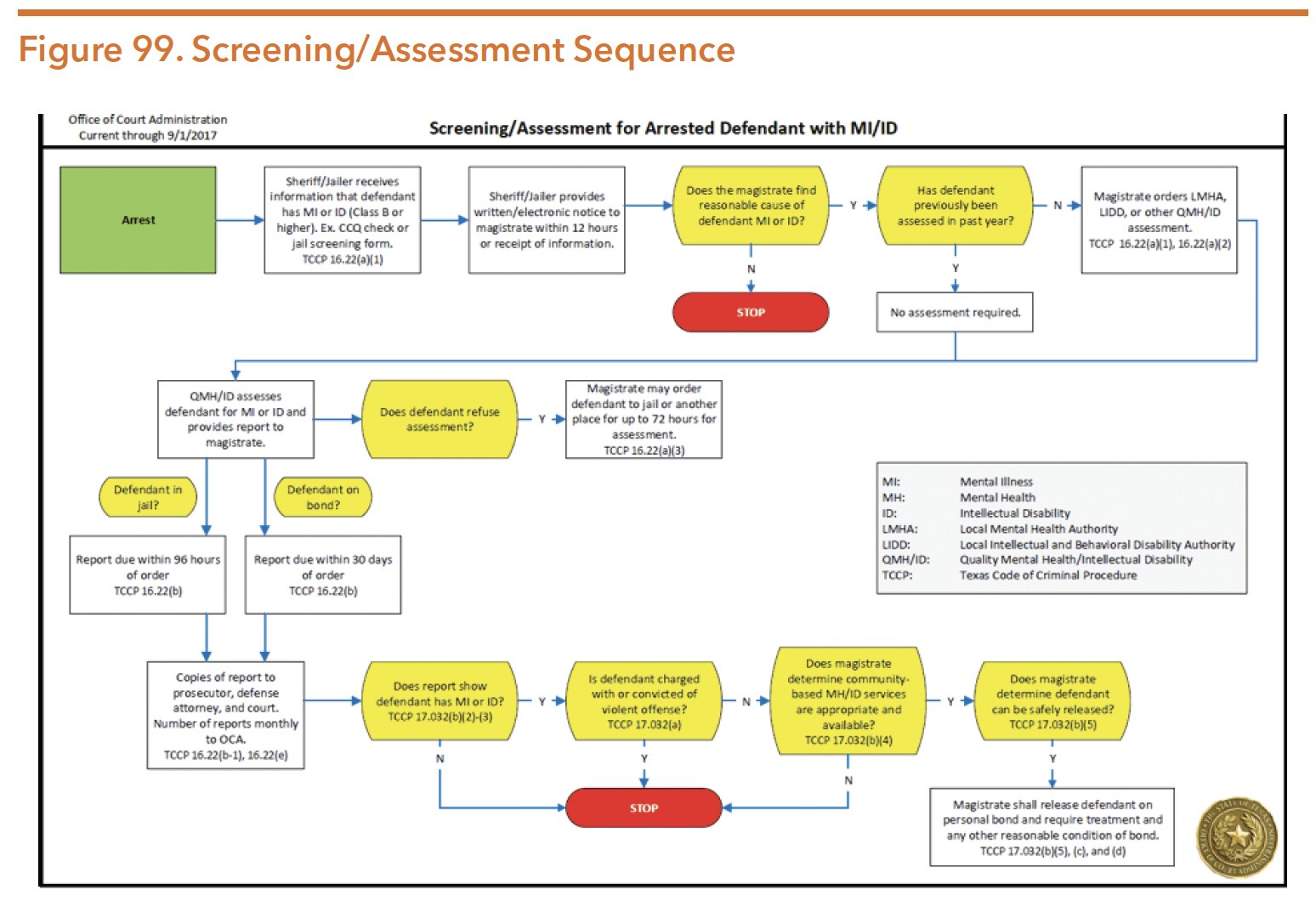

The flowchart below represents a sequence of criminal justice involvement for a person with mental illness or co-occurring conditions. A mental health public defender’s office is essential to successfully navigating through the listed statutes and applying expert knowledge and skills for the mental health defendant.

Source: “Screening/Assessment For The Arrested Defendant With Mental Illness Or IDD.” Txcourts.gov. N.p., 2017. https://www.txcourts.gov/media/1438893/screeningassessment-sep2017.pdf. Accessed 20 Mar. 2020.

The Bexar County Public Defender’s Office was created in 2005, first with an appellant public defender, and in 2015 it began representing defendants with mental illnesses at magistration. It has trial, appellate, mental health, and central magistration departments with a staff of 18. Of this number, 7 are full-time attorneys dedicated to representing clients with a mental illness. These attorneys represent both felony and misdemeanor mental health clients from magistration to civil commitment hearings.

In FY 2016-2017, the Bexar County Public Defender’s office reviewed 7,781 booking slips of defendants with an indication of mental illness. The program presented 424 cases before magistrates at Central Magistration (CMAG) in FY 2016-2017 in an attempt to get clients a mental health personal bond. Of the 424 presented cases, 305 were granted and effectively diverted into the Center for Healthcare Services (Bexar County’s LMHA) program. It was estimated that a total of 3,615.5 days of confinement were avoided in FY 2016- 2017 as a result of this program. Since 2015, the mental health personal recognizance bond jail diversion grant has successfully avoided approximately 6,255.1 days of confinement.

Successful reintegration into the community can be a challenge for justice-involved people. Peer education and peer support have been used for decades to support people in prisons without a specific focus on people with mental health conditions. Peer support for people with mental health conditions has become an established service in other contexts (e.g., reentry from state hospitalization), and interest is growing for the use of peer support in incarceration settings. Reentry peer support programs allow people with lived mental health and criminal justice experience to mentor others in the justice system who are beginning the recovery and reentryprocess. Certified peer support (CPS) specialists or “Peers” are able to share strategies, coping skills, and experiences with the state mental health system to help participants successfully navigate the difficult transition back into the community.

In 2015 legislators approved Rider 73 to the DSHS budget, which created a peer support reentry pilot program in Texas. In 2016 DSHS funded pilot programs in three locations: Harris County, Tarrant County, and Tropical Texas (which serves Cameron, Hidalgo, and Willacy counties); in the fourth quarter of FY 2016, the pilots had served 48 people. County sheriffs and LMHAs in each location used certified peer support specialists to help individuals with mental health conditions successfully transition out of local jails and into their communities.

The Hogg Foundation for Mental Health funded the program’s evaluation and released its formal results in January 2019. The evaluation included results of the impact of CPS specialists on recidivism and recovery of people in jail across each of the three project sites (Tarrant County, Harris County and the Rio Grande Valley). Between 2016 and 2018, CPS staff provided mental health peer support services to facilitate successful transition from incarceration to community-based services. Peer support services included building a relationship with an individual based on mutuality and unconditional regard, guiding the individual to identify strengths and priorities for needed services, and working with the individual to reduce barriers to support successful reentry into clinically appropriate community-based services.

Results from this independent evaluation suggested that peer reentry specialists leveraged and applied lived experiences to support client reentry, although quantifiable effects were detected only for criminal behavior outcomes. The statistics indicated that peers most often helped clients address housing and treatment needs, rather than criminal behavior directly. Peers reported applying their personal experiences to also assist clients in seeking treatment for mental health symptomology and employment. Thus, by helping the client with other needs, peers were able to impact criminal behavior. There were a number of structural barriers, such as limited access to housing and long wait lists for clinical care, that prevented peers from addressing client needs. Despite these barriers, the evaluation showed statistically significant declines in criminal behavior identified among program participants.

Reentry Peer Support

County jails are another part of the criminal justice system within Texas, and hold four types of individuals:

- People who have not been convicted of a crime and are awaiting trial;

- People convicted of low-level offenses who are sentenced for short durations;

- People convicted of an offense who are awaiting transport to state facilities; and