POLICY CONCERNS

- Maintaining quality, accessible services during the reorganization of the health and human services system.

- Tracking the usage and effectiveness of the Alternative Response System in the CPS investigative process.

- Increased focus on housing, employment and normalcy as crucial parts of recovery.

- Continued monitoring and prevention of child fatalities within the CPS system.

- Addressing disproportionality of minority and LGBTQIA youth in the CPS system.

- More individualized interventions and treatment plans for youth with dual diagnoses (i.e. mental health and substance use or intellectual/developmental disabilities).

- System-wide integration of trauma-informed practices into all levels of care.

- Improving support for youth transitioning from child to adult services (ages 17-24).

- Ongoing review of the barriers to implementation for the Foster Care Redesign Project.

FAST FACTS

In FY 2015:

- The Statewide Intake (SWI) division of DSHS received an average of more than 2,000 contacts per day related to allegations of abuse, neglect or exploitation.

- There were a total of 274,448 cases of alleged child abuse and neglect statewide.

- 4,047 investigations of child abuse/neglect were transferred to the new Alternative Response (AR) system after being deemed low acuity and low safety risk reports.

- 224,065 investigations of abuse/neglect were opened after CPS staff determined they met criteria for follow-up investigation.

- Of the remaining 176,868 investigations completed, 40,506 were confirmed as child abuse and/or neglect and 17,151 children were removed from their homes.

- 16,378 children were in the Texas foster care system as of August 31, 2015 (excluding the 11,517 children in non-foster substitute placements such as kinship care and DFPS adoptive homes).

- DFPS confirmed 171 abuse/neglect related fatalities of children, five of whom died while they were enrolled in the state foster care system.

- The prevalence of child abuse/neglect decreased slightly, from 9.2 confirmed cases per 1,000 children in 2014 to 9.1 confirmed cases per 1,000 children in 2015.

- Adult Protective Services (APS) completed 78,180 in-home investigations, with 43,759 of those investigations being validated and 12,876 of those receiving follow-up services.

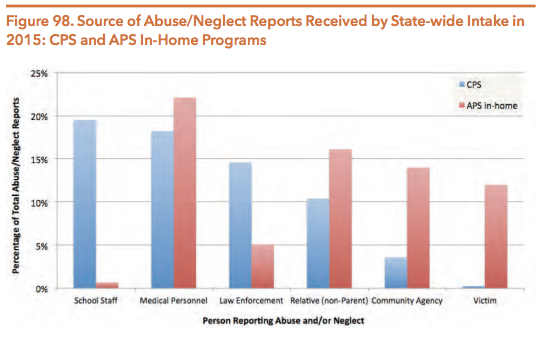

- The majority of allegations of in-home elder abuse were reported by medical personnel (21.8 percent), relatives (16.4 percent), community agencies (13.7 percent), or the victim themselves (11.8 percent).

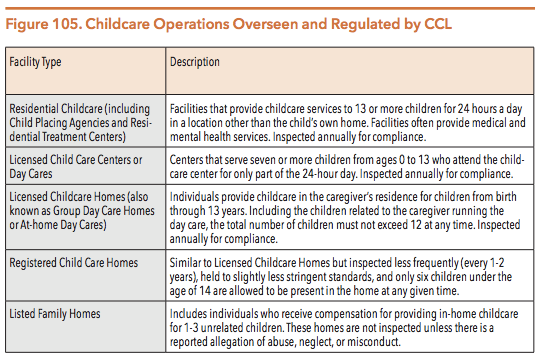

- The Child Care Licensing (CCL) division of DFPS oversaw approximately 20,882 daycare operations (or homes) serving 1.09 million children (as of mid-year 2015).

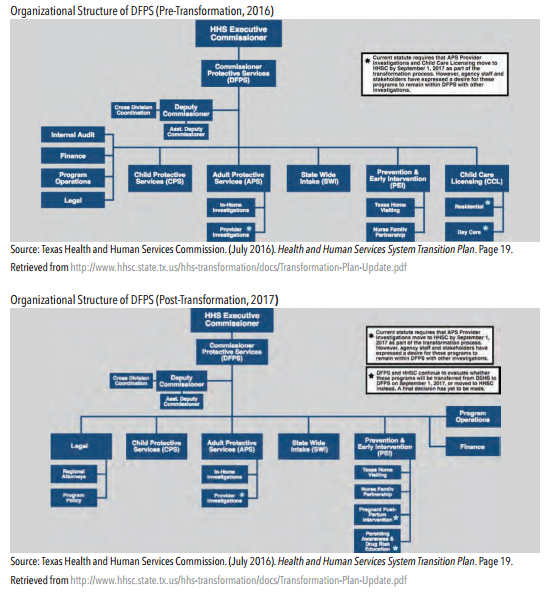

ORGANIZATIONAL CHARTS

Texas Department of Family and Protective Services

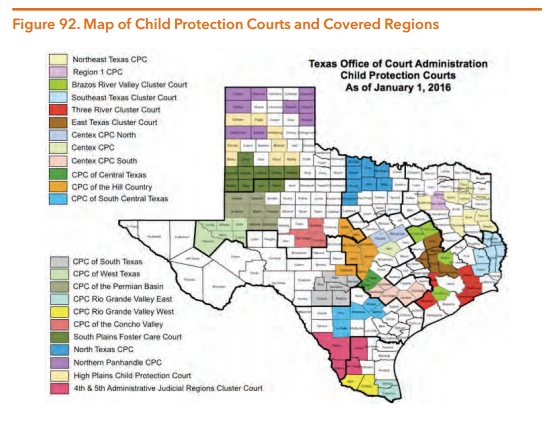

The Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS) is the state agency responsible for ensuring the safety of children, older adults, and adults with disabilities. DFPS provides services and supports to these vulnerable populations to reduce the likelihood of abuse, neglect, and exploitation. DFPS is headquartered in Austin and as of 2015 included 12,706 employees that work in 282 local offices in 11 geographic regions with regional headquarters. DFPS is divided into the same 11 regions as the Health and Human Services System — see Figure 12 in the HHSC section for a map of those regions. As Figure 92 below shows, Texas is also divided into several regional networks of child protection courts.

Data obtained from: Texas Office of Court Administration. (2016, January 1). Child Protection Courts Map.

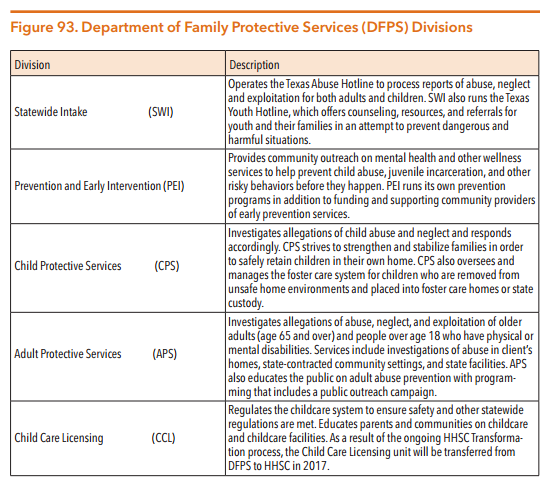

As Figure 93 shows, DFPS was comprised of five separate divisions before the reorganization of health and human services began.

Source: Texas Department of Family and Protective Services. (n.d.) Learn about DFPS.

Sunset and Transformation Highlights

In an effort to improve the efficient coordination and quality of state health services, the 84th Legislature followed recommendations from the Sunset Commission and passed SB 200 (84th, Nelson/Price), directing the reorganization and restructuring of the state agencies that provide health and human services in Texas, including behavioral health. As a result of the Sunset Commission’s evaluation process, DFPS was continued as a separate and distinct department with a new sunset date of September 1, 2023.

SB 200 (84th, Nelson/Price) takes a phased approach to reorganizing the Texas health and human services system. In phase one of the transformation, some prevention and client support programs from agencies other than DFPS will be moved to DFPS’ Prevention and Early Intervention (PEI) Division:

- The Texas Home Visiting program and the Nurse Family Partnership program, both previously managed by HHSC, were transferred to the PEI Division of DFPS on May 1, 2016.

- The Sunset Commission recommended that The Pregnant Post-Partum Intervention and the Parenting Awareness and Drug Risk Education programs previously managed by DSHS be moved to DFPS by September 1, 2017, but the HHSS transformation plan recommends that these two programs move to HHSC instead.

In phase two of the reorganization, all of the programs run by DFPS within the Child Care Licensing (CCL) division that regulate residential childcare and daycare facilities will be moved to new Regulatory Services Division within HHSC. Abuse and neglect investigations of community providers that are conducted by Adult Protective Services (APS) are also slated to move to HHSC’s Regulatory Services Division in 2017, but stakeholders have expressed a desire to keep all investigations within DFPS. The remaining four divisions within DFPS — State Wide Intake (SWI), Child Protective Services (CPS), Adult Protective Services (APS), and Prevention and Early Intervention (PEI) — will remain in DFPS and not be moved to HHSC.

DFPS will continue to operate as a separate agency during the transition and aims to maintain seamless delivery of all public health and behavioral health services during the reorganization process. SB 200 requires that HHSC further analyze the feasibility of moving all DFPS activities to the consolidated agency and requires that a report with recommendations for further reorganization of agencies to be submitted to the Transition Legislative Oversight Committee by September 1, 2018. For more detailed information on the transformation plan, see the Texas Environment section of this guide.

Changing Environment

PARENTAL RELINQUISHMENT OF CUSTODY TO OBTAIN MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES

In some instances parents or guardians have no other options to get their child needed mental health services and voluntarily relinquish their child to state conservatorship solely for the purpose of accessing those mental health services through DFPS. These children have serious mental health conditions and proper treatment is often expensive due to the need for temporary residential treatment or extensive outpatient supports. Some parents have insufficient insurance coverage while others lack insurance altogether, making it difficult to afford the mental health treatments that are necessary to guarantee safety in the household for themselves or other children. Parental relinquishment of custody to obtain critically needed mental health services has historically been considered as “Refusal to Assume Parental Responsibility” (RAPR) by DFPS, a form of neglect that results in the parents’ or guardians’ names being automatically added to the Texas Child Abuse/ Neglect Central Registry.

In 2013, the 83rd Texas Legislature began the initial work needed to address parental relinquishment of custody in Texas with the passage of Senate Bill 44 (83rd, Zaffirini/Burkett). In addition to ordering regular data collection and reporting on parental relinquishment solely to obtain mental health services for a child, SB 44 required DSHS and DFPS to jointly study policy changes that could reduce the number of children being placed into state custody (i.e. managing conservatorship) for this reason. Also in 2013, the 2014-2015 General Appropriations Act (S.B. 1, 83rd, Williams/Pitts) allocated $2.1 million to fund ten beds in private Residential Treatment Centers (RTCs) for children who are at risk of being relinquished into the state’s custody solely to obtain needed mental health services. This program — later expanded to a total of 30 beds— is known as the Residential Treatment Center (RTC) Diversion Bed Project.

Then in 2015, SB 1889 (84th, Zaffrini/Burkett) changed the definition of what constituted child neglect by a parent. SB 1889 requires DFPS to not include a parent or guardian’s name in a Child Abuse/Neglect Central Registry if they relinquish custodial rights only because they attempted and were unable to obtain needed mental health services for a child with a serious emotional disturbance (SED). SB 1889 also directed DFPS to review previous case files to remove names of parents and guardians from the Child Abuse/Neglect Central Registry that meet this criterion.

As a result of SB 1889 (84th, Zaffirini/Burkett), DFPS has overturned previous findings of Refusal to Accept Parental Responsibility (RAPR) and removed the names of approximately 172 parents and guardians from the Child Abuse/Neglect Central Registry who met the criteria set forth in SB 1889. The retrospective case review process found 888 unique cases dating from 2001 to 2010 that required review and notification letters were sent to the 73 overturned cases (i.e. 73 cases were previously ruled as child abuse/neglect but are now overturned as a result of SB 1889). Cases between 2011-2012 are still being reviewed and data from DFPS on the revised outcomes of those cases is still forthcoming, but the 2013-2014 review of 662 cases found an additional 37 cases that met criteria for review, 11 of which were overturned and resulted in removing the names of the parent(s)/guardian(s) from the Child Abuse/Neglect Central Registry.

In FY 2015, DFPS staff reviewed 954 cases that potentially met the criteria for being overturned by SB 1889:

- 88 cases from FY 2015 were overturned (i.e. no longer “Reason to Believe” abuse happened).

- 11 of those cases were offered and granted joint managing conservatorship (JMC).

- 77 of those cases were granted temporary managing conservatorship (TMC) and only one of those cases was later ruled to be “Reason To Believe” (i.e. the initial removal was deemed appropriate).

SB 1889 also required DFPS to adopt the new definition of neglect into their operating procedures so that no new parents are deemed RAPR solely for relinquishing custody to obtain needed mental health services that they could not otherwise obtain. While SB 1889 (84th, Zaffirini/Burkett) established that certain parents and guardians are not reported to the child abuse registry for relinquishing parental rights to obtain needed mental health services, the number of children entering DFPS care solely to obtain mental health services has increased since 2015. In just the first half of FY 2016, 76 cases were overturned out of the 382 total case files that were reviewed — almost as many cases as were overturned in all of 2015.

As part of the effort to help reduce the number of children entering into DFPS conservatorship solely to obtain mental health services, the 84th Legislature allocated $4.8 million to add 20 beds to the Residential Treatment Center (RTC) Diversion Bed Project that was started in 2013, making for a total of 30 beds. Between September 2013 and May 2016, a total of 179 children have been referred to the RTC Diversion Bed Project:

- 150 children were diverted from being relinquished to DFPS conservatorship,

- 66 children received services at a residential treatment center, and

- 28 children were ultimately removed from their family home and taken into DFPS conservatorship.

As of July 2016, a total of 22 children were on the waiting list for the 30 beds in the RTC Diversion Bed Project.

Finally, SB 1889 also requires DFPS to offer families joint managing conservatorship of a child before DFPS files a suit requesting managing conservatorship of that child, so long as the child “suffers from a severe emotional disturbance” and is entering into conservatorship to obtain need mental health services. SB 206 (84th, Schwertner/Burkett) also strengthened reporting requirements for voluntary relinquishments solely to obtain mental health services and required reporting of the number of subsequent joint and temporary managing conservatorships resulting from intervention via SB 1889.

There is still no available data on the number of families who have been offered or who have accepted joint or temporary managing conservatorships with the state, but that data will be included in the SB 1889 implementation reports that DFPS will release in November of each even-numbered year.

SENATE BILL 125: MANDATORY SCREENINGS FOR YOUTH ENTERING FOSTER CARE

The 84th Legislature passed a number of bills relating to trauma-informed care including SB 125 (84th, West/Naishtat), which requires children who are entering into DFPS conservatorship to receive a “developmentally appropriate comprehensive assessment” that includes a screening for trauma and mental health needs within 45 days of the child’s entrance into DFPS care. The uniform assessment adopted statewide for this purpose is the Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths assessment, or CANS — the same tool routinely used by LMHAs to qualify children for mental health services. In addition to completing the CANS assessment, DFPS is also now required to conduct interviews with several individuals in the child’s life who have knowledge about the child’s ongoing mental health needs. SB 125 (84th, West/Naishtat) established more consistent and thorough screening procedures for children entering into DFPS care, and these new procedures are aimed at placing children with complex needs in placements that will better fit their individualized needs — hopefully resulting in fewer placement changes and more long-term stability and success for children.

LAWSUIT AGAINST DFPS/CPS

The foster care system operated by DFPS came under increased public scrutiny after a class-action lawsuit was filed against DFPS in 2011 on behalf of all Texas children in foster care on a long-term basis. The case was originally brought forth by two advocacy groups — Children’s Rights and A Better Childhood. Over a dozen other advocacy organizations have since joined as plaintiffs in the case. The lawsuit specifically addressed how CPS treats children in the state’s Permanent Managing Conservatorship (PMC) program, specifically children who have been unable to find a permanent placement within a year of their initial removal from their home. In 2011, when the lawsuit was first brought against CPS, there were approximately:

- 12,000 children in Permanent Managing Conservatorship (PMC),

- 6,400 children in PMC for three or more years,

- 500 children in PMC for more than 10 years, and

- More than 1/3 of children in PMC experiencing five or more placements.

In December 2015, U.S. Federal District Judge Janis Graham Jack of Corpus Christi issued a ruling on the case, finding that the state had systematically violated the constitutional rights of children in PMC foster care. Judge Jack described the foster care system run by DFPS as one “where rape, abuse, psychotropic medication and instability are the norm,” where children “often age out of care more damaged than when they entered.” The state’s appeals against Judge Jack’s ruling have so far been unsuccessful, and several of the ruling’s reforms to improve the PMC program started being implemented in the beginning of 2016. These changes include:

- Addressing caseworker turnover and caseload size issues by directing DFPS to hire enough caseworkers to “ensure that caseloads are manageable” across the state.

- Addressing concerns of child safety in foster care placements by disallowing placement of children in foster group homes without 24-hour awake supervision and addressing regulatory lapses in the state’s “broken” residential licensing division.

Judge Jack appointed two special masters in March 2016 to help guide and oversee the changes to DFPS’ foster care system. The two transition masters, mediator and specialist attorney Francis McGovern and Kevin Ryan, former Commissioner of Children and Families for New Jersey, began their new roles working with DFPS on April 1, 2016. The co-transition masters will create a plan for addressing the capacity issues, defining “manageable” caseload sizes, and resolving other problems with the PMC program identified in the lawsuit. CPS caseworker turnover and high caseloads make it difficult for cases to be processed quickly and in some cases thoroughly, which leaves children in the foster care system longer and at greater risk of experiencing instability in their placements. Average CPS caseload sizes in Texas have fallen some in recent years — from 31 cases in 2014 to 28 in 2015 — but that still far exceeds the maximum number of cases (17) recommended in national best practices. Judge Jack estimated that the co-transition masters will cost roughly $3 to $4 million per year. See the Texas Environment section for further information on the ongoing court case against DFPS.

In the intervening time since the lawsuit against DFPS began, capacity issues and a lack of availability of homes within the foster care system have continued to be a problem. A series of policy changes at the beginning of 2015 made it more difficult for children to be placed in kinship placements (i.e. with extended family members). In 2015, child removals by CPS grew by 37 percent as a result of these stricter safety-screening standards, and short-term informal kinship placements fell by 56 percent during the same time. As a result of this shortage of available foster placements, Texas foster children waiting for placements have been forced to stay in less-than-ideal locations; 16 children spent at least two nights sleeping in CPS offices in February 2016 alone. 50 Capacity shortages are also not just an issue of numbers, but of matching each child to the appropriate setting for their needs, background, and identity. As former head of DFPS John Specia described it to the Senate Health and Human Services Committee in April 2016, “we may have enough beds for every child in care, but once you overlay specific needs (including location, gender, age and behavior), our capacity does not align.” Increasing the number of available foster homes is part of the foster care redesign pilot project in Region 3b (west of Dallas); from November 2014 to August 2015, total foster placement capacity increased by 20 percent, from 1,950 beds to 2,330 beds.

Texas Speaker of the House Joe Strauss has declared that fixing the foster care system is on the top of the legislative agenda for the 85th Legislative session in 2017.

FOSTER CARE REDESIGN

Foster care and mental health delivery systems overlap because nearly all of the youth entering into foster care have suffered traumatic experiences. Trauma inflicted by experiencing physical, psychological, or sexual abuse or chronic neglect has a profound effect on children. The effects of trauma can last a lifetime. Individuals who experience significant childhood abuse and family discord in their youth have a higher incidence of physical and behavioral health problems as adults. A youth who has experienced trauma is at higher risk of having issues with substance use, mental health (such as depression and suicide), promiscuity, and criminal behavior. Children in foster care have undergone abuse and neglect and as a result experience different degrees of traumatization. Mental health conditions are one of the consequences that typically result from traumatic experiences. However, children’s symptoms of trauma may sometimes be misinterpreted as deliberate problematic behavior or indicative of a condition unrelated to trauma.

A disconnected and uncoordinated foster care system is likely to aggravate childhood trauma and any other mental health conditions if they are not properly addressed with timely and appropriate care. Lack of permanency and consistency in childcare placements can also create trauma and exacerbate mental health conditions for children in foster care. A high number of placements is traumatizing for children who are navigating the foster care system, further elevating the need to embed trauma-informed care into CPS practices.

In an effort to reduce negative outcomes for children (such as victimization and fatality) in the foster care system, DFPS embarked on a Foster Care Redesign project in 2010 to improve outcomes for youth in the areas of safety, permanency, and wellbeing. The overarching goals of the Foster Care Redesign are to:

- Keep children and youth closer to home and connected to their communities and siblings.

- Improve the quality of care and positive outcomes for children and youth.

- Reduce the time to permanency for children in foster care.

- Reduce the number of times youth move between foster homes or other placements.

One of the biggest changes of the Foster Care Redesign has been the switch from service-based funding to performance-based funding. Under the previous system, payment was linked to a child’s service level (basic, moderate, specialized, or intensive) and placement type (Child Placement Agency, Emergency Shelter, General Residential Operation, or Residential Treatment Center). This reimbursement structure did not create incentives for a child to be moved to a lower service level. Through the redesign effort, payments are now tied to positive outcomes in the child’s care instead of their current service level, thereby encouraging children’s transition to lower service levels and corresponding overall reductions in the average cost-per-child.

The Foster Care Redesign also restructures service delivery so that care is coordinated from a Single Source Continuum Contractor (SSCC) rather than a compilation of DFPS contracts with over 300 private service providers. The goal of streamlining the delivery of care is to better coordinate services for families so that mental health services are more consistent across the state and readily accessible close to a child’s home and community, regardless of what part of the state they live in. Under the new system, an SSCC is required to provide a range of services for foster care youth in specific geographic catchment areas.

The Stephens Group, a business and government consulting agency, released a report in November 2015 that assessed the “status, policies and practices that currently exist between Texas Child Protective Services (CPS) and Child Placing Agencies (CPA) in providing behavioral health case management services to children with the highest needs”. Approximately 12.5 percent of children who are in DFPS conservatorship have been identified as having high needs, meaning they have “special medical, behavioral or emotional indicators, or are in the IDD (intellectual and developmental disabilities) population”. The report from the Stephens Group highlighted several areas of the redesigned foster care system that still need to be addressed including:

- Lack of a clear and consistent definition of what constitutes “high-need” within the child welfare system makes it hard for families and children with particularly complex needs to receive the specialized and intensive services they require to succeed.

- Intricacies of the mental health system and caseworkers’ inability to navigate and understand each part of the system leads to a lack of provider accountability and continuity of care as children move between service providers and systems.

- Gaps in training for both caseworkers and CPS foster care contractors make it difficult to provide high-needs children with “the right care, in the right setting, at the right time.”

- Escalation of needs and through under-utilization of mental health services provided through local mental health authorities (LMHAs), local IDD authorities, the Medicaid targeted case management benefit, and in-home supports.

- Lack of key performance measures make it difficult to hold CPAs or CPS caseworkers accountable for child outcomes while in DFPS care.

The report from the Stephens Group raised concerns regarding the effectiveness of the Foster Care Redesign for children who have mental health diagnoses or IDD. The report indicated concern that recommendations for care may be too standardized and do not adequately meet the individualized needs and abilities of families and parents with complex mixtures of mental health, IDD, and/or substance use issues. There is also a provision in the Foster Care Redesign that allows children with dual diagnoses (i.e. mental health disorders and IDD diagnoses) to be placed in institutions far from their home community, which likely causes trauma and may not produce the best outcomes. The instability and trauma associated with repeatedly removing children from their community and familiar support networks can have detrimental effects on long-term well-being. As an example of this disproportionate impact, the average number of placements for children in DFPS care is 2.7 while youth identified as having high needs have 5.7 placements on average, more than twice as many

The initial results are mixed on the implementation of the Foster Care Redesign program. As Judge Jack pointed out in Spring 2016, the program currently only covers about 800 children and is operating in only two percent of Texas counties. There is currently only one SSCC actively operating in Texas— All Church Home (ACH) Child Services, in the Fort Worth area. ACH’s Our Community Our Kids program serves as the SSCC foster care provider for a seven-county region that includes Erath, Hood, Johnson, Palo, Parker, Pinto, Somervell, and Tarrant counties. ACH expects to spend approximately $5 million of its own money over the course of the three-year contract, but representatives from the organization feel positive about the future of Foster Care Redesign as a whole. Data on the effectiveness of ACH’s program is forthcoming. Using data from the Region 3b service area (including Fort Worth and Dallas county), one study from the Perryman Group estimates that every dollar invested in the state’s foster care redesign will return $3.44 in state revenue and $1.66 in local revenue.

The most recent request for proposals (RFP) for Foster Care Redesign SSCC contracts was for DFPS Region 2 in Northwest Texas, and that RFP opened in Summer 2016. Additionally, one of the exceptional items (#4) in DFPS’ proposed 2018-19 budget is to “Strengthen and Expand High Quality Capacity and Systems in the Foster Care System”, which includes the expansion of the Foster Care Redesign program to eight new catchment areas and roughly half of children in paid foster care, at an initial cost of $101.3 million.

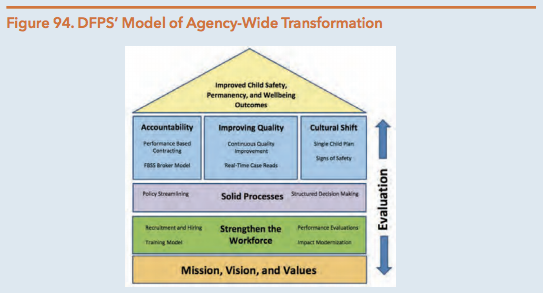

CPS “TRANSFORMATION” PLAN: REDUCE CASEWORKER TURNOVER AND CHILD FATALITIES

DFPS has been prioritizing “transformation” the past few years, a self-improvement process that is focused on making CPS a better place to work and a more effective system overall. As part of this transformation, CPS designed and implemented a competency-based training program known as CPS Professional Development (CPD). As a result of CPD, newly hired CPS caseworkers receive improved classroom and hands-on experience in addition to being assigned a mentor upon hiring, which enables caseworkers to get direct feedback from another worker and spend more time “learning and practicing skills in the field”. Combined with the new CPD training program, the transformation process also aims to decrease child fatalities in DFPS care by using uniform, step-by-step procedures and flowcharts for caseworkers who are assessing the immediate and long-term safety risks that children face. Figure 94 below shows the overarching philosophy and interdependent goals of the systemwide approach to transformation that DFPS is undertaking.

Source: Texas Department of Family and Protective Services. (April 2016). Progress Report to the Sunset Advisory Commission: Child Protective Services Transformation. Page 2.

In addition to the transformation focusing on the interdependent goals of a systemwide approach depicted above, the new DFPS co-transition specialists appointed by Judge Jack in March 2016 will be in charge of choosing and setting regulations for what constitutes a safe and appropriate number of cases for a caseworker to be in charge of at once. High caseloads for CPS workers can lead to failures to conduct routine visits, identify safety risks, and intervene appropriately. Having lower caseloads allows CPS caseworkers to be more effective and thorough in their work while providing needed attention and support to all vulnerable children.

The average caseload for CPS workers has improved in the last two years to about 31 or 32 active cases per worker in FY 2015. However, average caseloads remain significantly higher (almost double) than the 17 cases per caseworker recommended by the Child Welfare League of America. High caseloads can lead to high turnover of staff, discontinuity on cases, and negative outcomes for children. The turnover rate for workers at CPS increased from 25.2 percent in 2014 to 25.7 percent in 2015, and the turnover rate for supervisors increased even more – from 6.3 percent in 2014 to 9.5 percent in 2015. CPS worker turnover statewide was still at 23.0 percent in the second quarter of FY 2016, but statewide averages can have the unintended effect of hiding the fact that turnover rates in some counties have reached as high as 57 percent a year (Dallas County). Exit surveys explain some of the most common reasons case workers report leaving:

- Job stress

- Safety concerns (e.g. working in unsafe neighborhoods late at night)

- High caseloads

- Poor supervision and pay.

The new DFPS Commissioner Hank Williams has indicated that one of his priorities for the upcoming legislative session is to try to reduce CPS caseworker turnover by increasing pay and adding new caseworker positions to help reduce caseload sizes. For example, in DFPS’ proposed budget for FY 2018-19, one of the exceptional items (#2) requests $202.2 million in new funding to add hundreds of new CPS workers (e.g. CPS Investigation Caseworkers, CPS Kinship Caseworkers, SWI Intake Specialists) to reduce caseload sizes and subsequently improve the ability of DFPS to fulfill their main mission – protecting vulnerable populations from being subjected to abuse and neglect.

INCREASED FOCUS ON NORMALIZATION IN MENTAL HEALTH TREATMENTS AND INTERVENTIONS

The National Foster Care Youth & Alumni Council has defined normalcy as “the opportunity for children and youth in out-of-home placement to participate in and experience age and culturally appropriate activities, responsibilities and life events that promote normal growth and development.” DFPS encourages normalcy for children in care but foster families in particular receive mixed messages from caseworkers on what is and is not allowed. Many foster families fear regulatory or legal repercussions if a child is allowed to participate in an activity not specifically included in the child’s service plan. The Promoting Independence Advisory Committee has been a crucial part of the system-wide push towards less restrictive and more patient-centered services.

SB 830 (84th, Kolkhorst/Dutton) established an independent ombudsman office outside of DFPS (to be housed in HHSC) and required the new ombudsman to develop and implement statewide procedures to receive complaints from children and youth in DFPS conservatorship, provide any necessary assistance, and follow through with investigation.

Another bill, SB 1407 (84th, Schwertner/Dukes), encouraged age-appropriate normalcy activities for children in foster care, defined a reasonable and prudent parent standard for such decisions, shifted several decision-making responsibilities from the caseworker to the caregiver, and put liability protections in place for caregivers. SB 1407 also required training on normalcy for caregivers, staff, and Residential Child Care Licensing staff. This training is part of CPS’ larger focus on promoting normalcy by exposing children involved with CPS to activities and experiences that children outside of CPS care have the opportunity to experience in the normal course of life.

Funding

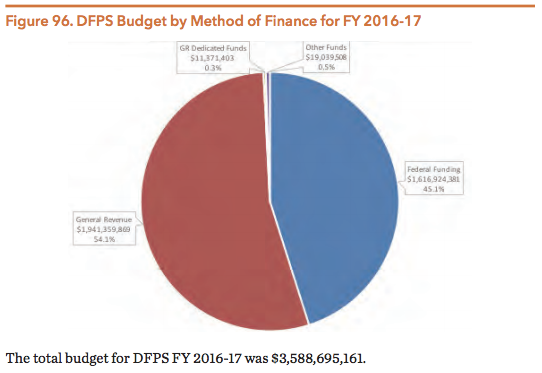

The Department of Family and Protective Services is jointly funded by both state and federal dollars. The budget for DFPS was roughly $1.375 billion in 2011 and $1.591 billion in 2015 — a 15.7 percent increase in that four-year period. In 2011, 57.4 percent of DFPS funding came from federal sources while the other 42.6 percent came from state sources (e.g. general revenue funds, GR-dedicated funds and other funding sources such as child support payments). By 2015, the federal share of funding for DFPS had dropped to 53.4 percent.

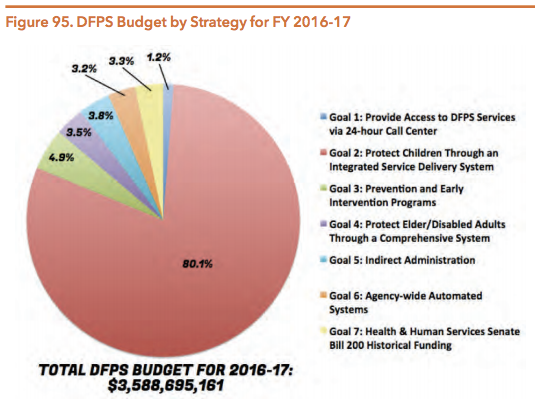

As Figure 95 shows, the vast majority of the DFPS budget (80.1 percent) goes towards the department’s CPS-related mission of protecting children by operating an integrated service delivery system.

Source: Texas Department of Family and Protective Services. (September 6, 2016). Legislative Appropriations Request for Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019. Pages 30-31.

Source: Texas Department of Family and Protective Services. (September 6, 2016). Legislative Appropriations Request for Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019. Pages 30-31.

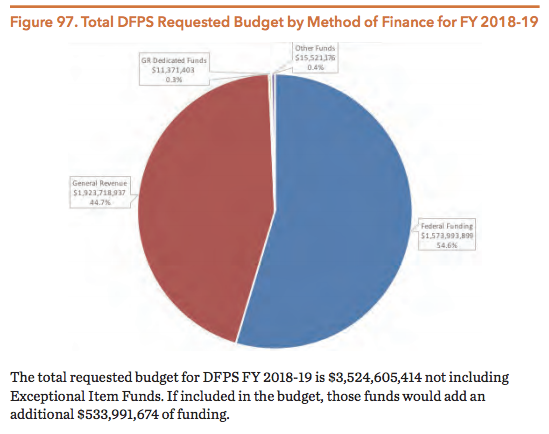

Source: Texas Department of Family and Protective Services. (September 6, 2016). Legislative Appropriations Request for Fiscal Years 2018 and 2019. Pages 30-31.

DFPS submitted a baseline budget request of $3.52 billion for the 2018-19 biennium (not including funds for exceptional items) — that is a net decrease of $64.09 million from the 2016-17 budget. Roughly $14.4 million in general revenue (GR) funds were cut from the DFPS legislative appropriations request for 2018-19 to comply with the legislature’s requirement to reduce GR expenditures across all agencies by four percent. However, the majority of this decrease in the 2018-19 legislative appropriations request is a result of the HHS Transformation process, which is moving the Child Care Licensing & Regulation ($94.9 million) and APS Provider Investigations ($24.3 million) divisions from DFPS to HHSC. Also as a result of the HHS Transformation, the Texas Home Visiting and Nurse Family Partnership programs will be moving from HHSC to DFPS, increasing the DFPS budget by roughly $10 million.

The 2018-19 legislative appropriations request for DFPS also has an increase in GR funds to account for caseload growth in specific entitlement programs: Foster Care ($27.8 million) and Adoption Subsidy/Permanency Care Assistance Payments ($25.7 million). As DFPS notes in their Legislative Appropriations Request for FY 2018-19, much of the need for increased state spending on services related to the foster care system is a result of both higher costs per foster care child and the nationwide trend of declining federal funding through the Title IV-E program:

“The decline in federal Title IV-E financial participation is the result of continuing erosion in the IV-E penetration rate – the percentage of children in foster care who are covered by IV-E. This erosion […] is the direct result of linking IV-E eligibility to the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) income and asset standards that were in place in 1996 [and] have not been increased or indexed for inflation in more than 15 years. Applying those same standards today means that a child has to come from a poorer household than in 1996.”

Statewide Intake (SWI)

The Statewide Intake (SWI) division of DFPS operates the Texas Abuse Hotline and is the central hub for all incoming reports of abuse, neglect, and exploitation. SWI receives the initial call and then routes the information to the appropriate department (i.e. CPS, APS, or Child Care Licensing, in addition to client service programs in DSHS and DADS). SWI handles reports of abuse for adults and children in all types of settings, including private homes, childcare facilities, nursing homes, and state facilities.

The average hold time for a phone call to the Statewide Intake department has increased by almost a minute in the last four years — from 7.3 minutes in 2011 to 8.2 minutes in 2015.

In 2015, SWI employed approximately 418 FTE staff, 309 of which worked as intake specialists. Those intake specialists handled 781,935 abuse- and neglect-related contacts during 2015 — that’s an average of more than 2,000 reports of abuse or neglect per day. Those 781,935 reports corresponded to the following departments within DFPS:

- 280,895 cases for CPS investigators (274,448 reports of alleged child abuse/neglect and 6,447 case related special requests),

- 110,290 cases for APS In-Home Investigators (110,277 reports of alleged adult abuse/neglect and 13 case related special requests),

- 12,952 cases for APS Facility Investigators,

- 3,700 cases for Day Care Licensing (DCL) Investigators within the CCL division, and

- 4,516 cases for Residential Child Care Licensing (RCCL) within the CCL division.

While 77.6 percent of the reports of abuse/neglect received by SWI in 2015 came via phone, a significant number of reports came through the Internet (18.5 percent) and mail/fax (3.2 percent). Figure 98 below shows some of the most common types of reporters of abuse and neglect for children and in-home investigations of adult victims.

Source: Texas Department of Family Protective Services. (2016). 2015 Annual Report and Data Book. Page 6.

The SWI division of DFPS also operates the Texas Youth Hotline (1-800-98-YOUTH or www.TexasYouth.org), an easily accessible resource that provides “counseling, resources, and referrals to youth and their parents in an effort to prevent abuse, neglect, truancy, delinquency, and running away from home.” The Texas Youth Hotline provides both crisis intervention and information regarding community resources.

Child Protective Services (CPS)

Child Protective Services (CPS) is responsible for responding to and investigating allegations of child abuse and neglect, providing at-home services for families and youth in need, removing children from unsafe environments, managing the foster care system, as well as assisting youth to successfully transition out of the CPS system and into safe environments. Thus, CPS interacts with children at three stages: investigating abuse allegations, placing youth in emergency custody or inpatient treatment, and transitioning youth back into normalcy and a healthy environment.

In FY 2015, a total of 290,471 children statewide were alleged victims of abuse or neglect in 274,448 cases (some cases involve more than one child) of alleged child abuse and neglect — a more than 23 percent increase from the number of CPS reports of child abuse/neglect in 2011. Of those 274,448 allegations in 2015:

- 46,336 allegations were screened out for not meeting criteria for abuse/neglect

- 4,047 low acuity and low-risk cases were transferred to the new Alternative Response system (1.5 percent of all allegations)

- 224,065 investigations were opened and 176,868 investigations were completed.

- 40,506 of completed investigations were confirmed abuse or neglect cases (confirmed is defined as “based on [a] preponderance of evidence, staff concluded that abuse or neglect occurred”).

- In the 40,506 confirmed cases of child abuse or neglect, there were 66,721 unduplicated confirmed child victims (i.e. some cases have more than one victim).

- Following different degrees of CPS intervention, 17,151 children were removed from their homes in FY 2015 in order to keep them safe from an abusive and/or neglectful caregiver or environment.

- DFPS confirmed 171 abuse/neglect related fatalities of children, five of whom died while they were enrolled in the state foster care system.

CHILD ABUSE/NEGLECT AND CPS INVESTIGATIONS

CPS investigates abuse and neglect allegations to make a determination as to whether there is a threat to the safety of the children in their home environment. During child abuse and neglect investigations, a CPS worker screens the child’s behavioral health, basic physical condition, and the safety and livability of their living environment. Based upon in-person interviews with alleged victims, photographs of injuries (if present) and documented conversations with other adults in the child’s life (e.g. teachers and siblings), the CPS worker will assess the mental health and psychosocial functioning of each child and make referrals for additional behavioral health services and assessments as necessary. If the caseworker determines that a child is not safe, then the caseworker initiates protective services. This could include family-based protective services such as outpatient engagement while the child remains in the home, a court petition to remove the child from the home, and/or legal action to terminate parental rights.

A child is placed in foster care after other parent engagement services and outpatient treatment options have been exhausted. As of August 31, 2015, there were 16,378 children in the Texas foster care system (excluding the 11,517 children in nonfoster substitute placements such as kinship care and DFPS adoptive homes). A total of more than 47,000 children were in DFPS custody at some point during FY 2015, and 31,200 of them lived in some type of a foster care placement. Hispanic (39.2 percent) and Caucasian children (32.0 percent) make up the majority of children in foster care, with African-American children (22.4 percent) as the third most prevalent racial group. However, when you take into account the racial demographics of Texas children as a whole, African-American children (11.4% of Texas child population) are overrepresented in the foster care system — see the Disproportionality and Racial/Ethnic Diversity of Children and Youth section in this chapter for further information.

More than 40 percent of children in DFPS conservatorship are in kinship placements. When it is unsafe for a child to remain in his or her home and there are no appropriate family or friends who can provide shelter and care for that child, CPS will petition the court for temporary legal conservatorship. When family and kinship placements are unavailable, CPS may place a youth in a variety of different settings, including:

- Emergency children’s shelters

- Foster group homes

- Foster family homes

- Residential group care facilities

- Facilities overseen by another state agency

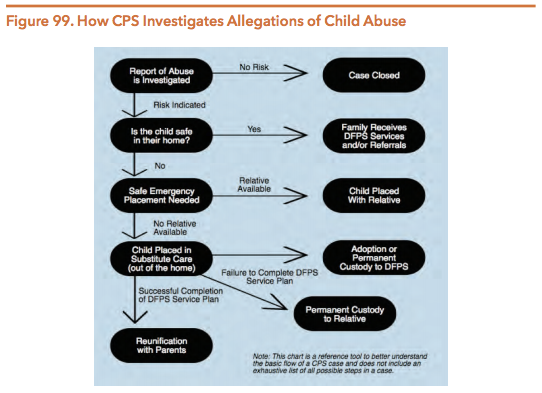

Figure 99 illustrates the CPS investigation process upon receipt of an allegation:

Source: Texas Department of Family and Protective Services. (2016). Annual Report and Data Book 2015.

ALTERNATIVE RESPONSE SYSTEM

The CPS Alternative Response (AR) system aims to ameliorate the stress of a CPS investigation and provide services to more families in need by adapting the typical investigation process when workers identify a lower-risk allegation. In doing so, CPS provides a non-adversarial means of dealing with less serious cases of abuse and neglect in a more client-centered and less intrusive manner. In considering diverting a case to AR, staff considers the type and severity of the allegation, any history of previous reports, and the willingness of the family to participate and be involved with support services. AR, also known at the national level as “differential response,” places an emphasis on reinforcing family strengths, fostering parental involvement, and the development of support systems.

The AR used by Texas’ CPS is characterized by the following features:

- The CPS worker conducts “assessments”, not investigations.

- A completed assessment does not declare a formal finding of abuse or neglect.

- The report does not designate an alleged perpetrator (i.e. the name of the perpetrator is not added to the Child Abuse/Neglect Central Registry).

- The CPS worker connects families with appropriate service providers.

- The AR process as a whole encourages collaboration with families and a focus on treatment and rehabilitation.

National research has found that differential response systems lead to more positive outcomes related to child safety, better family engagement, increased community involvement, and improved worker satisfaction. Despite higher initial investments, this approach is more cost-effective in the long run because it reduces the need for long-term services and more costly intensive interventions. AR engages parents, prompts them to identify their strengths, and connects them to providers to help address behaviors that may be harming a child’s cognitive, social, emotional, or physical development.

Texas DFPS began AR pilot programs in FY 2015 in three regions — Amarillo, Dallas and Laredo. A few cases have been transferred to Tyler and Midland, where DFPS plans to have AR fully functioning by May 2016. If the current success of AR continues and there are no unforeseen barriers to implementation, DFPS expects AR to be used in all regions statewide by the end of 2017.

A total of 4,047 allegations of child abuse or neglect were transferred to the new AR System in FY 2015, only 1.5 percent of the 274,448 total reports of abuse or neglect for the year. CPS caseworkers have received training on how to implement the AR protocols and only 230 of the 4,047 cases that were initially referred to AR in FY 2015 were later transferred to full abuse/neglect investigations.

ACCESSING MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES

SUPERIOR HEALTH SYSTEM (STAR HEALTH)

In 2008, the STAR Health program was created to provide children in foster care with primary care and behavioral health services using a managed care delivery model. Superior Health Plan contracted with the state to run the STAR Health program and has been operating the program since its inception. The statewide program was designed to improve the continuity and coordination of care by improving data sharing and access to health services for children in the foster care system.

In FY 2014, 30,732 children were enrolled in STAR Health (including those in kinship care, foster youth up to age 22, and former foster youth receiving transitional Medicaid services). STAR Health requires that each foster care child has access to primary care physicians, behavioral health clinicians, specialists, dentists, vision services, and more. Behavioral health services offered by Superior include:

- Psychiatric services

- Psychological testing (including screening, assessment, and diagnosis)

- Rehabilitation skills training

- Detoxification services

- Depression Disease Management Program

Historically, the lack of a central medical records system for children in DFPS care created serious problems such as the over-prescription of medications or the sudden discontinuation of medications when a child’s placement changed. To help solve this continuity of care issue, DFPS began using a computer-based system called the Health Passport to track and monitor the medical information of every child enrolled in the STAR Health program. The Health Passport follows children wherever they go so that every caregiver, DFPS staff member and medical professional working with a child has a full understanding of his or her past and current treatments and can access that information in one central, easy-to-find location. Each child’s Health Passport is available online through a password-protected website and can be accessed by DFPS staff and medical consenters. While the Health Passport is not a full and complete medical record, it provides claims data on pharmacy, dental, vision, physical, and behavioral health services provided to each child. Information on a child’s drug allergies can also be directly uploaded to the Health Passport website and the system can alert medical professionals and caregivers if there is a potentially unsafe drug interaction or allergy.

FORMER FOSTER CARE CHILDREN PROGRAM (FFCC) AND MEDICAID FOR TRANSITIONING FOSTER CARE YOUTH (MTFCY)

Many foster children who age out of the foster care system lose health insurance coverage. Many children in foster care experience trauma or other mental health conditions that impact them even after they have left the child welfare system. Foster care alumni are more likely than young adults in the general population to rely on public assistance, experience difficulties in finding and keeping a stable home, and have a high risk for physical and mental health concerns. Thus, retaining health insurance for former foster care children for a longer period of time may lead to better outcomes by ensuring that they have more consistent and reliable access to the mental health care services and supports needed for recovery and longterm wellbeing.

As a component of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the Former Foster Care Children Program (FFCC) provides extended health insurance coverage to former foster care children under the age of 26. With the implementation of the FFCC plan, more adults formerly in the foster care system will have health insurance coverage up until their 26th birthday. Effective January 2014, former foster care children receiving healthcare services through one of the insurance plans that existed at that time — Medicaid for Transitioning Foster Care Youth (MTFCY) or Former Foster Care in Higher Education Program (FFCHE) — were transitioned to FFCC. Those who do not qualify for FFCC will still be covered under MTFCY as long as they meet MTFCY income requirements.

There are two groups of young adults previously in CPS conservatorship that are ineligible for access to post-care health services: individuals originally from Texas who have aged out of the foster care system in another state and individuals who have aged out of the Texas foster care system and have since moved to another state. Young adults who do not qualify for FFCC may purchase health insurance through the Health Insurance Exchange if they have sufficient resources and/or federal marketplace subsidies, or they may still qualify for Medicaid.

Unlike Medicaid or other foster care insurance plans, FFCC has no asset, income, or educational requirements for coverage. There are two FFCC insurance plans based on the age of the applicant: STAR and STAR Health. The services provided by each of these plans vary — see HHSC section for more information on STAR and STAR Health services and eligibility.

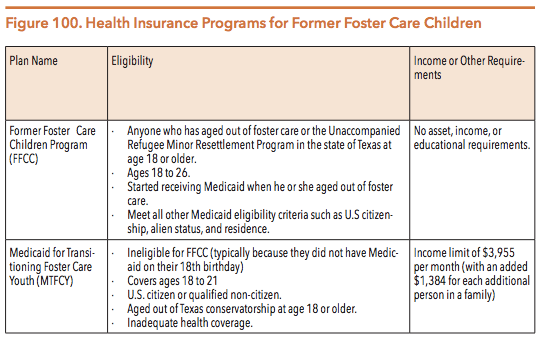

See Figure 100 for an overview of existing health insurance programs for former foster care children.

Source: Texas Department of Family Protective Services. (n.d.) Medical Benefits; and Texas Law Help. (n.d.) Free Health Insurance Medicaid for Aged Out Foster Youth Ages 18-25 Former Foster Care Children’s (FFCC) Program and Medicaid for Transitioning Foster Care Youth (MTFCY): September 2015 version. Pages 4 and 5.

INSTITUTIONAL RESIDENTIAL SERVICES

While the state recognizes that it is preferred that children grow up in family, home-based environments, some children in the custody of the state are placed in congregate care facilities. Prior to placing a child in foster care, the court is required to consider temporary placement with a relative if possible. If this option is not available or appropriate, the child may be placed in a foster home with foster parents, a foster family group home, or a general residential operations (GRO) facility. A GRO is a congregate care facility that provides residential services for 13 or more children up to the age of 18 years. GROs are licensed by DFPS and include longterm residential facilities that provide basic childcare, emergency shelters in which children are typically placed for less than 30 days, and more long-term residential treatment centers (RTC). An RTC provides care and treatment services exclusively for children with complex emotional and psychological needs.

As of August 2015, there were a total of 235 licensed GROs regulated by DFPS — 74 of those GROs are classified as RTCs and another 124 of them provide treatment services for children with emotional disorders. RTCs had capacity to provide services to a total of 3,483 children in August 2015, while GROs had capacity to serve a total of 9,026 youth. DFPS provides an online search tool that lists all of these child-care facilities in the state.

CONTINUING ISSUES

CHILD FATALITIES IN THE CPS SYSTEM

Child fatalities continue to occur in the Texas child welfare system, but the rate of these deaths has decreased in recent years. DFPS reports that a total of 171 children in Texas died as a result of child abuse or neglect in FY 2015 — a 36 percent decrease from FY 2011, when there were 231 such deaths. The majority of these deaths were neglect-related (59 percent) as opposed to abuse-related (41 percent).

The rate of child abuse and neglect-related deaths per 100,000 Texas children is also dropping, down from 3.5 in 2011 to 2.3 in 2015. Overall abuse and neglect-related child fatalities in Texas have fallen in recent years. Confirmed deaths from physical abuse or intentional trauma dropped by 26 percent between 2011 and 2015, and confirmed deaths from neglect (e.g. drowning or death from unsafe sleeping conditions) decreased by 22.5 percent during that same time period.

It is important to look at trends in past child deaths in order to understand the risk factors that can be used by DFPS to prevent child abuse and neglect-related fatalities in the future. Some of the most salient risk factors for child abuse or neglect-related fatalities can be drawn out from the following pieces of information:

- While the majority of the 171 child deaths in FY 2015 continued to involve Anglo (51) and Hispanic (67) children, African-American youth are more disproportionately represented in child abuse and neglect-related death statistics, with a 4.2 per capita fatality rate.

- A history of child maltreatment and domestic abuse increases child fatality risks; 47 percent of families who had a confirmed child abuse or neglect-related fatality in 2015 had a history of prior involvement with CPS.

- More than 11 percent of abuse- and neglect-related fatalities involved families and/or perpetrators with an open and active CPS case at the time of death.

- Between 39 percent (FY 2015) and 48 percent (FY 2014) of abuse and neglect-related child fatalities include a parent or guardian actively using substances and/ or actively under the influence of substances that impacted their ability to protect and care for the child.

- Children under the age of three accounted for roughly 80 percent of all confirmed child abuse and neglect-related deaths between 2011 and 2015.

- Mothers (36 percent) and fathers (27 percent) represented the majority of primary perpetrators in child abuse or neglect-related deaths in FY 2015, but boyfriends (18 percent) and baby sitters/day cares (7 percent) accounted for roughly a quarter of perpetrators in these cases.

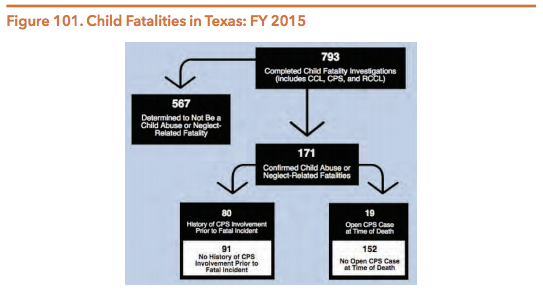

Figure 101 provides details on the child fatalities in Texas in FY 2015:

Source: Texas Department of Family and Protective Services. (2016, April). Child Abuse and Neglect Fatalities Annual Report: FY 2014 and FY 2015 Analysis. Page 50.

There are many possible reasons for this dramatic decline in child abuse and neglect-related deaths in Texas:

- DFPS formed the Office of Child Safety in 2014, tasked with independently analyzing child abuse and neglect fatalities and the risk factors and systemic issues that perpetuate these fatalities,

- Increased community-level interventions and initiatives to combat child deaths, such as the Blue Ribbon Task Force and state and local Child Fatality Review (CFR) Teams,

- More consistent system-wide guidelines (beginning in 2012) for CPS workers who handle child fatality cases involving co-sleeping, drowning, firearm accidents, suicide, and vehicle safety.

- More accessibility and availability of preventive, community-based behavioral health services,

- Improved training and availability of treatment resources for the medical community, including the Medical Child Abuse Resources and Education System (MEDCARES), and

- A bigger focus on public health approaches to reducing three of the most prevalent causes of neglect-related child fatalities: unsafe sleeping arrangements, unsafe vehicles, and injury resulting from domestic violence.

Following internal rule changes within DFPS to address abuse and neglect related deaths of children in foster care, HB 781 (84th, Burkett/Zaffirini) addressed the issue by requiring foster care providers and child placing agencies to include more rigorous minimum caregiver training requirements before contracts and placements are approved. New regulations were put into place that enforce stricter monitoring of foster care homes; some of these new rules include:

- Additional interviews with neighbors, clergy, school employees, community members, and family members living outside the home,

- Assessment of personal relationships and parenting of foster parents, and

- Review of household finances and past law enforcement calls to the home.

In addition to these stricter screening requirements and the new child fatality trainings and risk assessment tools that are part of the CPS transformation process (see Changing Environment Section), child placing agencies (CPAs) are also now required to closely monitor changes in all foster homes (such as job losses, marriages, divorces, frequent visitors, and family additions). The goal of this change is to provide more oversight and protection of foster care children and prevent not only child fatalities, but also unnecessary trauma and/or neglect. Another bill passed in 2015 that should improve safety for children in foster care going forward is SB 830 (84th, Kolkhorst/Dutton), which created an independent ombudsman for youth in foster care to help streamline and standardize investigations into reports of abuse and neglect.

DISPROPORTIONALITY AND DIVERSITY OF CHILDREN AND YOUTH IN CPS

Racial and Ethnic Diversity in CPS

The disproportionate representation of African American children and youth in the statewide CPS system continues. While not overrepresented at the statewide level, Hispanic children in Texas are another group disproportionately represented at certain points in the child welfare system. This overrepresentation of African American and Hispanic youth receiving child welfare services has been present in all 50 states and is not unique to Texas.

- A number of theories have been offered as explanations for the disproportional representation of certain racial and ethnic groups in the child welfare system, including:

- Increased parent and family risks,

- Increased rates of poverty and exposure to neighborhood risks and harms,

- Societal disparities that make it difficult for parents to obtain stable housing and employment,

- Racial biases among CPS workers and individuals who report abuse and neglect, and/or

- Lack of cultural competence among CPS investigators and caseworkers.

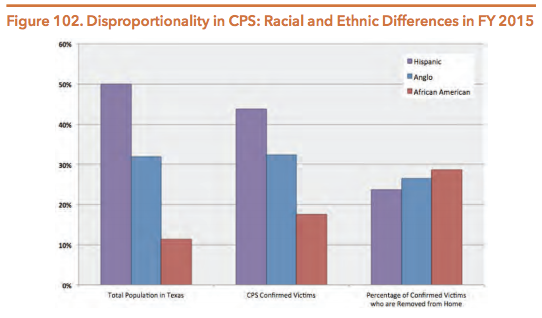

Figure 102 shows the ethnic and racial profile of children in Texas compared with children invoved in the CPS system at various levels:

Source: Texas Department of Family and Protective Services. (2016). 2015 DFPS Data Book. Page 42.

According to 2015 data, African-American children also wait much longer to be adopted (median of 12.3 months) compared to Hispanic children (9.6 months) and Anglo children (9.6 months). And while Asian children account for a very small proportion of the confirmed victims of abuse (.6 percent) and the number of children removed from a home because of safety concerns (.4 percent), Asian children in Texas typically wait longer than any other group to be adopted (13 months). In FY 2015, there were a total of 6,888 children waiting to be adopted in Texas.

While DFPS’ main goal is to address disproportionality through providing comprehensive and quality services through its regular programming and service delivery for all children, CPS has made some attempts in recent years to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in the child welfare system. For example, CPS started to provide some caseworkers with Poverty Simulation trainings in 2013. The goal of the simulations is to increase understanding and awareness about the realities and struggles that families in poverty face. CPS has also created disproportionality specialist positions and worked to increase staff diversity and collaboration with the Disproportionality Advisory Committee to reduce disparities. New DFPS caseworkers (both CPS and APS) are also now required to take a racial diversity training called, “Knowing Who You Are: Racial and Ethnic Identity Training.” To date, more than 5,000 workers have taken the training and DFPS reports that feedback from caseworkers has been very positive.

Another key component to addressing racial and ethnic disproportionality is CPS’ increasing support for kinship care — placing the child with a relative or someone close to the family so that children maintain connections to their community, family, support network and culture. Unfortunately, individuals who take on this kinship responsibility aren’t eligible to receive support services like Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) or Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits. CPS provides only limited financial help to encourage kinship placements. Once kinship placements take place, programs like the Family Group Decision Making (FGCM) model are essential support services that can help strengthen bonds and support a successful transition to the kinship placement so that the child does not have to deal with the trauma and instability associated with having to move multiple times.

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex and Asexual Youth (LGBTQIA)

With the increasing national focus on the rights of same-sex couples following the Supreme Court’s ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges, the conversation over disproportionality has expanded to include lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex and asexual (LGBTQIA) youth who are also over-represented in the child welfare system. The stigma associated with LGBTQIA identity makes this population more vulnerable to both trauma and mental health conditions such as depression, substance use, and heightened risk of suicide. That stigma can also lead to an under-utilization of social supports (e.g. family or church clergy) and services (e.g., school-based counseling) if the child feels discriminated against or not accepted. Due to a lack of reporting and the fact that sexual orientation is self-identified and gender identity is fluid, it is difficult to determine the actual number of LGBTQIA youth in the foster care system. However, the National Resource Center for Youth Development reports that LGBTQIA youth are overrepresented in foster care, accounting for between 5 and 15 percent of all youth in foster care.

Research studies show that LGBTQIA youth have an increased risk of experiencing several different negative situations and outcomes compared to their heteronormative peers:

- LGBTQIA youth who experience family rejection have a greater chance of having mental health issues in adulthood and are significantly more at risk for suicide attempts, depression, and substance use. One study found that over 30 percent of LGBTQIA youth reported suffering physical violence at the hands of a family member after coming out.

- Higher rates of harassment, exclusion and unfair treatment due to negative social attitudes.

- Difficulty finding a foster family that understands, accepts, and is responsive to their full range of needs and identity. One study found that up to 78 percent of LGBTQIA youth in foster care were either removed or ran away from their foster placements as a result of encountering hostility toward their sexual orientation or gender identity.

- Disparities for LGBTQIA foster care youth continue into adulthood, as studies show that LGBTQIA former foster care youth are less financially stable as adults than their heterosexual peers.

There are currently no policies in Texas specifically addressing the needs of LGBTQIA youth in the state’s foster care system and there is no required data reporting on the number of LGBTQIA youth awaiting adoption in comparison to their heteronormative peers. Increasing family and caregiver support services will likely support the well-being of LGBTQIA children in Texas and reduce both their safety risks and likelihood of entering into the foster care system.

PSYCHOTROPIC MEDICATIONS IN FOSTER CARE

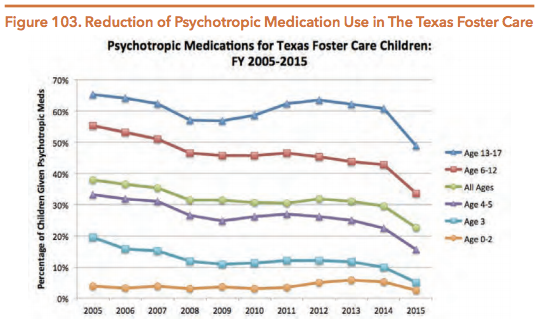

Foster children historically have been disproportionately treated for their behavioral health needs with psychotropic medications, drugs that affect an individual’s mind, emotions, and behavior. Psychotropic medication prescriptions for foster youth in Texas reached a peak in 2004, when close to 42 percent of all children in foster care were prescribed at least one psychotropic medication. A 2011 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) showed that in Texas, children in foster care were prescribed psychotropic drugs at rates 2.7 to 4.5 times higher than children not in foster care.

Even when effective in treating mental health conditions, psychotropic medications also carry significant and potentially long-lasting side effects, including trembling, decreased/increased appetite, weight gain, headaches, nausea, and increased risk of suicidal thoughts. Usage of psychotropic medications may also result in longterm effects such as stunted physical development. One research study showed that nationally, 10 percent of foster kids received antipsychotic medications, a powerful subset of psychotropic medications that can carry significant side effects in children.

Over the past decade, Texas has undertaken a series of different steps to better regulate and monitor the prescription of psychotropic medications for foster care children. Following the alarming rates of prescriptions in foster care in 2004 and subsequent increased media focus on the issue, HHSC, DSHS and DFPS released Psychotropic Medication Utilization Parameters in 2005 that established standards and requirements for the prescription of psychotropic medication. The goal of the parameters was to encourage clinically appropriate and informed usage of psychotropic medications.

Source: Texas Health and Human Services Commission. (2016). “Update on the Use of Psychotropic Medications for Children in Texas Foster Care: Fiscal Years 2002-2015”.

As shown above in Figure 103, psychotropic medication prescriptions for foster care youth have declined significantly in recent years, particularly in 2014 and 2015. This reduction is the result of over a decade of efforts by legislators and advocates to address the issue of overprescribing psychotropic medications for children in foster care. A few recent successes include:

- The passage of HB 915 (83rd, Kolkhorst/Nelson), which improved accountability and regulation of psychotropic prescriptions, required additional training for adults authorized to consent to medical care for foster children, required a doctor’s office visit every 90 days for children on psychotropic medication, created a medical consenter informational brochure and youth transition plan for children taking prescription medications, and required notification to biological parents of their child being prescribed psychotropic medications.

- HB 915 (83rd, Kolkhorst/Nelson), which created provisions to strengthen informed consent in prescribing psychotropic medications to children in state custody. Guardians ad litem and attorneys ad litem are now required to discuss with youth clients the medical and mental health care they are receiving and ask for their input. They are also now required to explicitly inform youth ages 16 and older that they may petition the court to be their own medical consenter. By involving individuals who can consent to medical care on behalf of the child, the child, and the judiciary system, everyone involved in a child’s care can be kept abreast of the child’s medical history.

- The creation of the Health Passport discussed previously, which allows DFPS staff, medical professionals, foster parents and caregivers to track and easily access each child’s medication history and medical information in one central online location.

- The establishment of one managed care organization (MCO) providing all pharmacy and acute care utilization for children in foster care, allowing for improved information sharing and streamlined decision making regarding past and current treatments.

As a result of these and other changes, the percentage of children in Texas foster care being prescribed any psychotropic medication has dropped from 37.9% in 2005 to 22.6% in 2015 (see Figure 103 above). Looking more closely at children taking multiple medications, Texas has reduced the number of children in foster care prescribed two or more psychotropic drugs by 71 percent since 2004 and reduced by 73 percent the number of children taking five or more psychiatric medications.

TRAUMA-INFORMED CARE

Youth who are in child welfare systems nationally and in Texas are at greater risk for trauma-related mental health and substance use conditions than children in the general population, and the overwhelming majority of children who enter the foster care system experience trauma as a result of neglect or abuse. Many children in foster care also experience trauma as a result of multiple removals and placements in different foster homes and shelters, and nearly half of youth in the child welfare system have clinically significant emotional or behavioral problems. Rates of behavioral problems, developmental delays, and need for psychiatric intervention for foster care youth range from 60 to 80 percent. Professionals who interact and work with these children must therefore be cognizant of their trauma-related needs and increased potential for mental health care.

Trauma-informed care recognizes the effects of trauma on the individual, and provides care that is evidence-based and tailored to an individual’s needs and unique experiences. It therefore provides a non-pharmacological approach to healing that decreases reliance on psychotropic medications and increases placement stability. Trauma-informed care is not a discrete intervention, but rather is a treatment framework that strengthens service delivery at all levels of care. In a trauma-informed system, every component of the service system is evaluated and reframed with an understanding of the role that trauma and violence play in the lives of people seeking behavioral health services.

Awareness of an individual’s trauma-inducing experiences can help workers and caregivers to avoid any re-traumatization that may occur during the delivery of traditional services or daily living. Understanding the effects of trauma can provide better insight into a child’s trauma reminders, stress signals, coping mechanisms, behavioral tendencies and cognitive development. As a result, trauma-informed care can provide communities, parents, schools, and caseworkers a better set of skills for understanding how to approach traumatized children and provide them the services and supports needed.

The push for trauma-informed care in Texas gained traction in 2013 with three bills that expanded education and training on trauma and trauma-informed care. While these bills did not directly modify DFPS operations, they had a definite impact on children receiving services through DFPS:

- SB 1356 (83rd, Van de Putte/McClendon) required trauma-informed training for probation officers, juvenile supervision officers, and court-supervised community-based personnel.

- SB 7 (83rd, Nelson/Raymond) ensured that professionals working on behavioral health intervention teams have training in trauma-informed practices.

- SB 152 (83rd, Nelson/Kolkhorst) required direct care staff at state hospitals to have training in trauma-informed care.

Then in 2015, the 84th Legislature significantly expanded and improved trauma-informed care within DFPS. SB 125 (84th, West/Naishtat) mandated that children entering into DFPS care receive a comprehensive assessment that includes a screening for trauma within 45 days of their entry into services. DFPS continues to promote trauma-informed practices by operating and maintaining its own trauma-informed care training program for a number of different groups, including:

- Court-appointed special advocates (CASA workers),

- Child advocacy centers (CACs),

- Foster parents and kinship caregivers,

- Adoptive parents, and

- DFPS caseworkers and supervisors.

Prevention and Early Intervention (PEI)

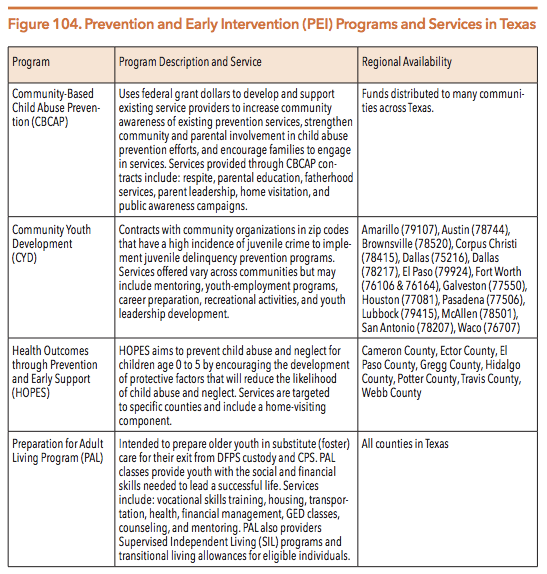

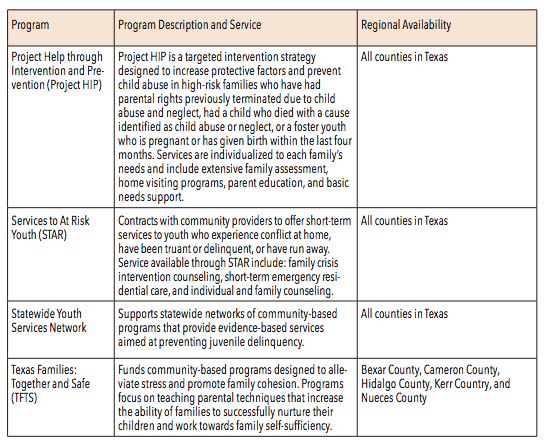

The Prevention and Early Intervention (PEI) division of DFPS partners with community providers and families to prevent abuse, neglect, truancy, runaway, and involvement with law enforcement. Community-based early intervention strategies and programs can address mental health conditions by providing timely access to services and reducing disparities for low-income and minority populations who may not have access to private providers or specialists. Additionally, these programs may identify youth at risk of developing mental health and behavioral health conditions and link them to treatment to prevent negative outcomes such as homelessness, family separation, poverty, removal from the home, incarceration, gaps in school enrollment and attendance, or complete dropout from school altogether. Programs and outreach efforts coordinated through this division address negative outcomes and try to provide services for youth before they are in crisis.

In FY 2015, 75,449 people were served by PEI programs — an almost 4.5 percent increase over the number of individuals receiving PEI services in FY 2014. Figure 104 lists the various programs and services provided through the PEI division of DFPS.

Sources: Texas Department of Family and Protective Services. (2016). DFPS Annual Report 2015. Pages 20-23; and Texas Department of Family and Protective Services. (n.d.). Prevention and Early Intervention (PEI) Programs.

Adult Protective Services (APS)

The Adult Protective Services (APS) division of DFPS investigates allegations of abuse, neglect, and exploitation for specific groups of people. APS provides services for individuals age 65 or older and adults age 18-64 who are:

- Living at home with a mental, physical and/or intellectual/developmental disability,

- Living in state hospitals, contracted inpatient facilities, state-supported living centers (SSLCs) and Intermediate Care Facilities for Intellectual Disabilities and related conditions (ICF/IDD),

- Receiving community-based services from DSHS or DADS (e.g. LMHAs and IDD providers) or

- Receiving services contracted through an HHS agency or MCO.

Investigations by APS involve both in-home investigations and facility investigations. Reported allegations can include self-neglect, abuse of parents by their adult children, physical and emotional abuse by caregivers, financial exploitation (e.g. taking social security checks or misusing a joint bank account), sexual assault, and any other forms of abuse, neglect or exploitation. These investigative and support services help to protect the mental health and wellness of persons with disabilities and aging Texans.

The population of Texans aged 65 and older reached 3,225,614 in 2015, about 11.6 percent of Texas’ total population, and that number is expected to increase to 18 percent in the next 20 years. Since 2000, individuals age 65 and older have been the fastest growing age group in Texas. This growth will likely lead to an increased demand for mental health services in the future as more individuals in the “baby boomer” generation become eligible for Medicare and other social services that are tailored to older Americans. Because Medicare does not have financial requirements for eligibility like Medicaid and all individuals over age 65 are eligible, many individuals who do not receive publicly-funded health services as adults begin receiving them at age 65 when they enter Medicare. The rising costs of prescription drugs will also continue to increase the overall cost of the Medicare program as baby boomers become eligible for Medicare coverage.

The incidence of adult abuse, neglect and exploitation per 1,000 Texans aged 65 or older has fallen in recent years, from 12.4 percent in 2011 and 10.4 percent in 2013 to 8.9 percent in 2015. There were 110,277 reports made of in-home abuse/ neglect of adults in FY 2015, with the majority of reports initiated by medical personnel (21.8 percent), relatives (16.4 percent), community agencies (13.7 percent) and the victim themselves (11.8 percent). Adult children were the most common perpetrators of APS investigations into in-home maltreatment (38 percent). The following breakdown shows the outcomes of the 110,277 reports of in-home abuse or neglect made to APS in 2015:

- 78,180 completed in-home investigations

- 43,759 separate instances of validated in-home allegations

- 29,442 of the validated in-home allegations received services (67.3 percent)

As mentioned earlier, APS conducts abuse and neglect investigations in facilities in additions to client’s private homes. In regards to investigations of abuse or neglect in residential facilities (i.e. state hospitals, SSLCs, ICF/IDDs and certain contracted inpatient facilities), APS completed 11,935 facility investigations into reports of abuse or neglect of adults in FY 2015. The majority of facility abuse/neglect allegations were for individuals enrolled in Home and Community-Based Service Programs (32.3 percent), State-Supported Living Centers (31.1 percent), and State Hospitals (21.3 percent). Roughly 10 percent (1,192) of all allegations of abuse or neglect in adult facilities in 2015 (11,935) were confirmed after an investigation by APS.