*Note: If you find the text on some of the images blurry or hard to read, right-clicking the image and then selecting “open image in new tab” may improve the issue.

Policy Concerns

- Impacts of COVID-19 on the veteran population and TVC operations.

- Continued expansion of veteran peer specialist services for mental health and substance use.

- Long waiting lists for mental health services with the Veteran’s Health Administration.

- Coordination of federal and state services.

- High risk of post-traumatic stress disorder among veterans.

- High rates of suicide and easy access to lethal means such as firearms among veterans.

- High rates of homelessness among veterans.

- Lack of supports for veterans returning to civilian life after deployment.

- Lack of access to mental health services and supports in rural areas of the state.

- Sexual assault and mental health effects on women veterans.

Fast Facts

- As of September 2017, Texas was home to over 1.6 million veterans of the armed forces, more than any other state except California. While the national Veteran population is predicted to decline from 20.8 million in 2015 to 12.0 million in 2045, Texas is projected to have the most veterans of any state by 2020.

- The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is America’s largest integrated health care system, providing care at1255 health care facilities, including 170 medical centers and 1074 outpatient sites of care of varying complexity (VHA outpatient clinics), serving 9 million enrolled veterans each year.

- By September 2017, women comprised 11.2 percent of the total Veteran population in Texas, higher than the national average of 9.41 percent. By 2045, women are projected to make up 19.8 percent of all living veterans.

- In 2015, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) accounted for the most service-connected disabilities for women Veterans at 11.8 percent. Major depression was the second highest at 6.5 percent.

- Nearly 70,000 Texas Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans will confront a mental health condition.

- While serving in the military, 55 out of every 100 women and 38 out of every 100 men report having been sexually harassed (including offensive comments about a person’s body or sexual activity, displays of pornographic material, and unwanted sexual advances). Additionally, 23 out of 100 women reported sexual assault. These statistics include only Veterans who use VA health care.

- Veterans exhibit significantly higher suicide risk compared with the U.S. general population. About 16.8 veterans died from suicide each day in 2017.

- Sixty-nine percent of all veteran suicides nationally occurred with the use of a firearm, compared to Texas, where over 75 percent of veteran suicide deaths occurred by use of a firearm (2012-2016).

- 41 percent of VHA patients have a diagnosed mental illness or substance use condition.

- The number of veterans experiencing homelessness declined by five percent between 2017 and 2018 and has dropped by 48 percent since 2009.

- On a single night in January 2018, veterans accounted for just under 9 percent of all homeless adults. Of these, 62 percent were staying in emergency shelters or transitional housing programs. Men accounted for about 91 percent veterans experiencing homelessness (34,412 veterans). A higher percentage of veterans experiencing homelessness were white (58 percent) compared to all people experiencing homelessness (49 percent).

TVC Acronyms

COVID-19 – Coronavirus disease of 2019

HHSC – Health and Human Services Commission

PTSD – Post-traumatic stress disorder

SMVF – Service members, veterans, and families

MFVPP – Military Families and Veterans Pilot Prevention Program

TBI – Traumatic brain injury

TVC – Texas Veterans Commission

VA – Veterans Affairs

VCL – Veterans Crisis Line

VHA – Veterans Health Administration

VISN – Veterans integrated service networks

VMHP – Veterans Mental Health Program

Retrieved from Legislative Budget Board (2020). Texas Veteran Commission, Legislative Appropriations Request Fiscal Years 2022-2023. Retrieved from http://docs.lbb.state.tx.us/display.aspx?DocType=LAR&Year=2014

Retrieved from Legislative Budget Board (2020). Texas Veteran Commission, Legislative Appropriations Request Fiscal Years 2022-2023. Retrieved from http://docs.lbb.state.tx.us/display.aspx?DocType=LAR&Year=2014

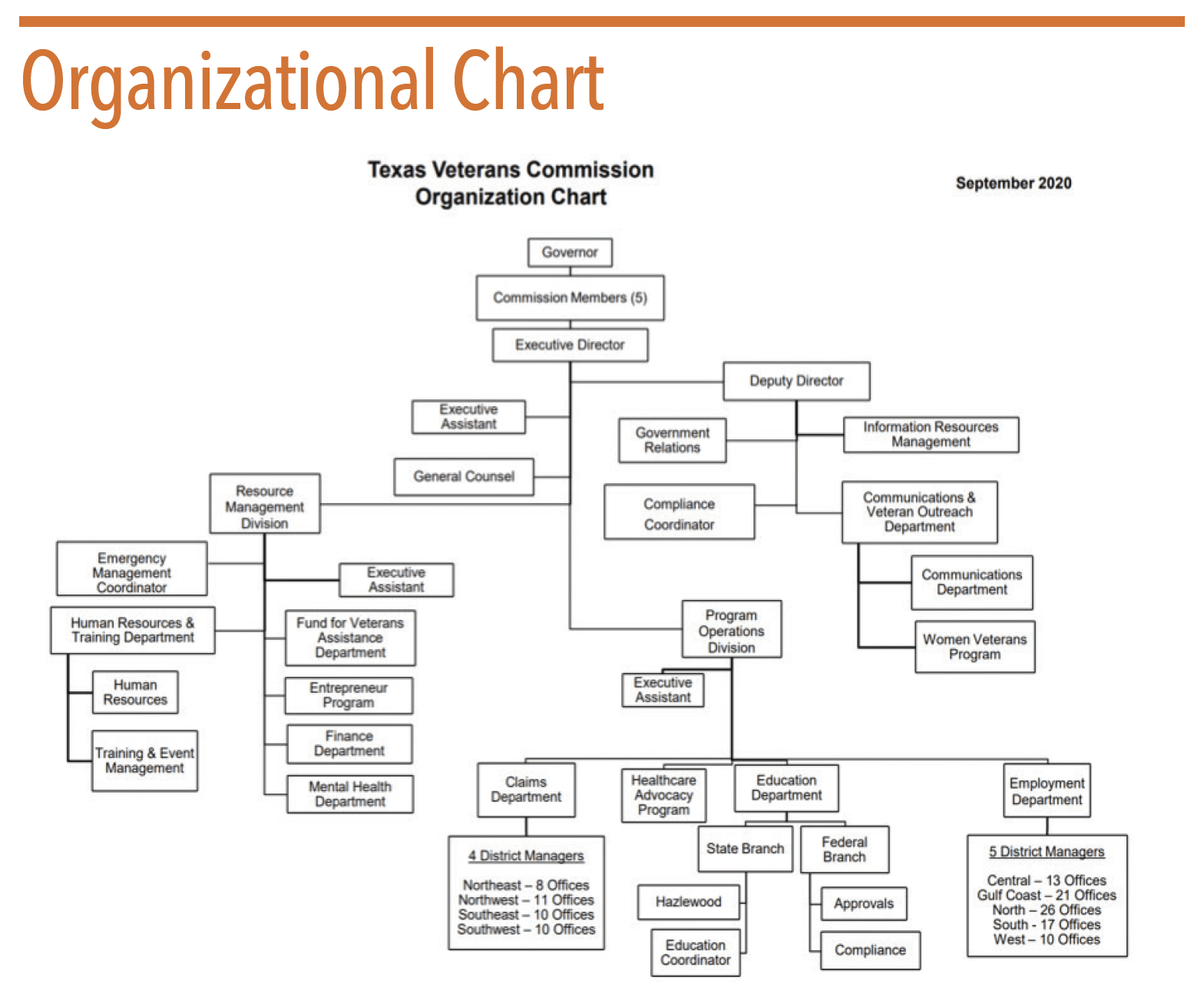

Overview

The Texas Veterans Commission (TVC) serves veterans and their dependents in all matters pertaining to veterans’ disability benefits and rights. TVC is Texas’s designated agency to represent the state and its veterans before the US Department of Veterans Affairs, with the mission of advocating for and providing superior service to improve the quality of life for all Texas veterans, their families, and survivors. The Commission submitted the TVC Strategic Plan for Fiscal Years 2019-2023 to the governor in June 2018. The plan is available at https://www.tvc.texas.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/TVC_Strategic_Plan_2019-2023_Final.pdf.

TVC also submitted the Operating Budget For FY 2020 to the governor and the Legislative Budget Board in December 2019. It can be viewed at https://www.tvc.texas.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/FY2020-TVC-Operating-Budget-FINAL.pdf.

TVC represents veterans in filing Veteran Affairs (VA) disability claims and during VA appeals processes, and it assists dependents with survivor benefits. Additionally, TVC focuses on the following eight program areas, which impact veterans’ ability to access behavioral health services:

- Claims Representation and Counseling

- Veterans Employment Services

- Veterans Education

- Veteran Entrepreneur Program

- Health Care Advocacy

- Veterans Mental Health Program

- Women Veterans Program

- Fund for Veterans’ Assistance.

The US Department of Defense Military Health System is responsible for providing health care to active duty and retired US military personnel and their families. For more information, visit www.health.mil.

Texas is home to nearly 1.6 million veterans of the armed forces whom represent 7.94 percent of the adult population, higher than the national average of 6.6 percent. The national veteran population is predicted to decline from about 20 million in 2017 to around 13.6 million by 2037 and to about 12 million by 2045. Texas is soon expected to surpass California as the number one state where veterans reside. Veterans face a myriad of challenges as they transition from active duty to civilian life. Among these challenges is an increased risk for behavioral health conditions. About 14 percent of veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars are diagnosed with PTSD. In comparison, less than 7 percent of American adults in the general population will experience PTSD at some point during their lifetime, with women being about twice as likely to develop it as men. In addition to combat trauma, sexual assault while in military duty (referred to as military sexual trauma) can also result in symptoms of PTSD (the most common mental health diagnosis pertaining to military sexual trauma).

Among women who use the VA to access health care, 23 out of 100 report having been sexually assaulted (unwanted physical sexual touching that involves some form of coercion) while in the military. Additionally, 55 out of 100 women and 38 out of 100 men report having been sexually harassed, which includes behavior such as offensive comments about a person’s body or sexual activity, displays of pornographic material, and unwanted sexual advances while in the military. Thus, veterans are at increased risk for developing mental health conditions and substance use problems stemming from their military service.

Veterans have the option to receive mental health care from the VA. PTSD, substance use conditions, and anxiety are the most commonly reported conditions for veterans receiving services through the VA.

Veterans with mental health and substance use conditions face a number of increased risk factors including: chronic homelessness, suicide, a wide range of serious medical problems, premature mortality, and incarceration. According to a study conducted by the RAND Center for Military Health Policy Research, less than half of returning veterans needing mental health services receive any treatment at all, and of those receiving treatment for PTSD and major depression, less than one-third are receiving evidence-based care. While COVID-19 may have affected the number of veterans seeking services in various parts of the state, as of June 2020 there was an average wait time of:

- 22 days to be seen at the only clinic within a 50-mile radius across Sheppard Air Force Base, TX;

- 23 days to be seen at the only clinic within a 50-mile radius across Beeville, TX; and

- 68 days to be seen at the only clinic within a 50-mile radius across Legrange, TX.

Long wait times contribute to higher risk of suicide among Texas veterans. A September 2019 report from the US VA’s Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention showed that mental health conditions (including bipolar, personality disorder, substance use, schizophrenia, depression, and anxiety), inpatient mental health care, prior suicide attempts, prior calls to the Veterans Crisis Line, and prior mental health treatment were all associated with increased likelihood of suicide. Male suicide rates are highest, and firearms are the number one cause of suicide death. See the Veteran Suicides section below for more information.

Changing Environment

Veterans’ mental health is a focus for many lawmakers in Texas. A variety of legislation was filed in the 86th legislative session to address veterans’ access to mental health treatments and supports. Some of the veteran-related legislation that was passed impacted TVC directly, while other bills were directed toward policies and inititaives of the Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) Mental Health Program for Veterans. In this Changing Environment section, we are including legislation impacting veterans’ mental health and substance use regardless of the agency impacted. Detailed breakdowns of bills can be found in the Hogg Foundation for Mental Health’s Texas 86th Legislative Session Summary: https://hogg.utexas.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/86th-Legislative-Summary.pdf.

Legislation from the 86th Legislative Session

HB 4429 (86th, Blanco/Menendez) included the local delivery of mental health first aid to veterans and their immediate family members in the Mental Health Program for Veterans. SB 822 (86th, Nelson/Flynn) shifted the administration responsibilities of the Texas Veterans + Family Alliance grant program from a nonprofit or private entity to HHSC, aligning with similar community mental health grant programs. It also created a matching requirement of 50 percent non-state funds for counties with a population of less than 250,000 and 100 percent for counties with a population of more than 250,000.

HB 1, Appropriations, Article II (86th, Zerwas/Nelson) included HHSC mental health and substance use-related riders. Budget Rider 59 allocated $5 million in general revenue each fiscal year to administer a mental health program for veterans. Budget Rider 61 allocated $20 million in general revenue in FY 2020 to operate a grant program to support community mental health programs providing services and treatment to veterans and their families. Both will require a legislative report by December 1, 2020.

HB 3980 (86th, Hunter/Menendez) directed the Statewide Behavioral Health Coordinating Council to create a report on suicide rates in Texas and prevention efforts. HCR 148 (86th, Landgraf) established June as Veteran Suicide and PTSD Awareness month for 10 years. SB 601 (86th, Hall/Birdwell/Buckingham/Nichols/Watson/Flynn) mandated that TVC publish needs assessment results online. SB 1180 (86th, Menendez/Lopez) mandated that Veteran Treatment Court statistics are reported by the TVC, including funding pertaining to grants. SB 1443 (86th, Campbell/Flynn) permissioned the Texas Military Preparedness Commission to consider mental health support and infrastructure development as part of their evaluations when examining grant applications.

Of bills that failed to pass, HB 2307 (86th, Rosenthal) and HB 4513 (86th, Hunter) are most notable. HB 2307 would have required military cultural competency training for personnel by grant recipients providing mental health services to veterans in order to receive funding. HB 4513 would have required TVC to employ and train mental health professionals to assist the Texas Department of State Health Services to administer the mental health program for veterans.

Funding

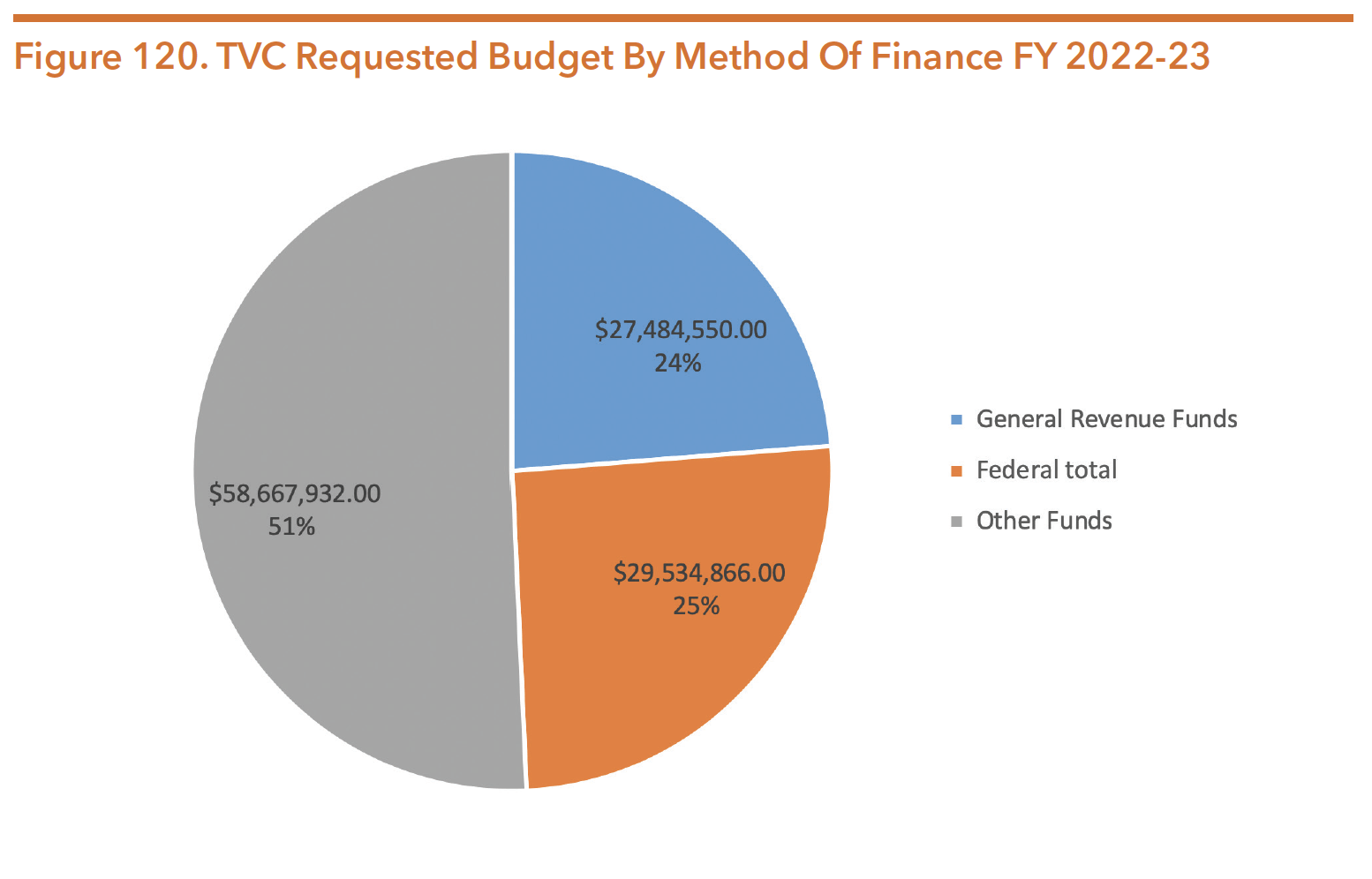

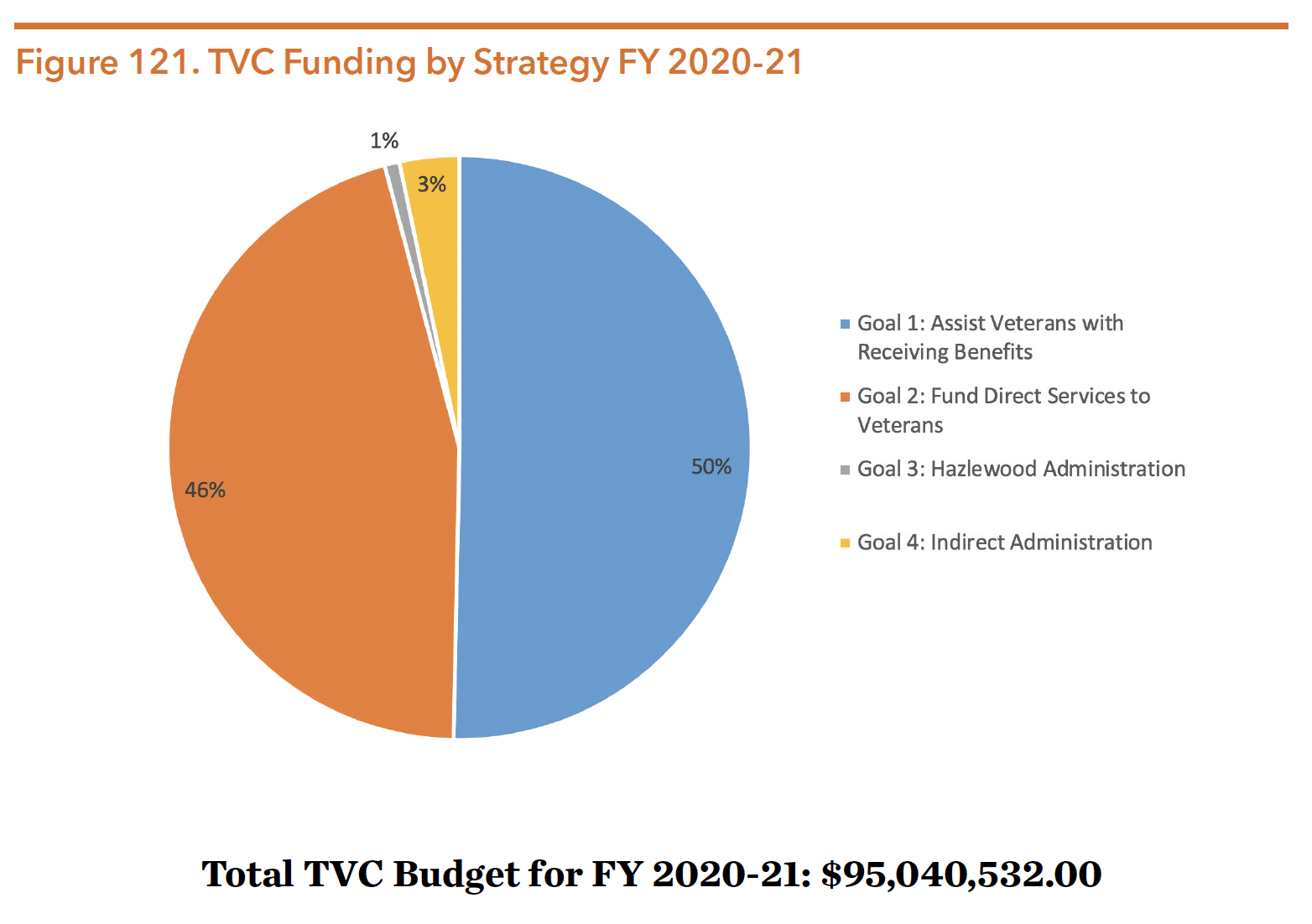

TVC receives about 74 percent of its funds from the state (e.g., general revenue and other funds), and about 26 percent from federal dollars. The agency’s budget increased over 3.6 percent from about $91.730 million in FY 2018-19 to almost $95.041 million in FY 2020-21. Most of TVC’s dollars come from funds other than general revenue and federal dollars, with a large percentage coming from the Fund for Veterans’ Assistance. In terms of goals, the overwhelming majority of TVC funding goes towards helping veterans receive benefits and for funding direct services to veterans. For FY 2022-23, TVC is requesting more than $115.687 million, plus another $2.429 million in Exceptional Items Requests.

* Note: TVC is not part of the Health and Human Services enterprise.

Source: Zerwas & Nelson. (2019). H.B. No. 1 General Appropriations Act Eighty-Sixth Legislature. Retrieved from https://capitol. texas.gov/BillLookup/History.aspx?LegSess=86R&Bill=HB1 *Other funds include: Fund for Veterans Assistance, Appropriated Receipts, Interagency Contracts, License Plate Trust Fund No. 0802

Source: Legislative Budget Board (2020). Texas Veteran Commission, Legislative Appropriations Request Fiscal Years 2022-2023. Retrieved from http://docs.lbb.state.tx.us/display.aspx?DocType=LAR&Year=2014 *Other funds include: Fund for Veterans Assistance, Appropriated Receipts, Interagency Contracts, License Plate Trust Fund No. 0802

The total requested TVC budget for FY 2022-23 is $115,687,348. If included in the budget, the Exceptional Items Requests would add an additional $2,429,169.

Source: Zerwas & Nelson. (2019). H.B. No. 1 General Appropriations Act Eighty-Sixth Legislature. Retrieved from https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/86R/billtext/pdf/HB00001F.pdf#navpanes=0

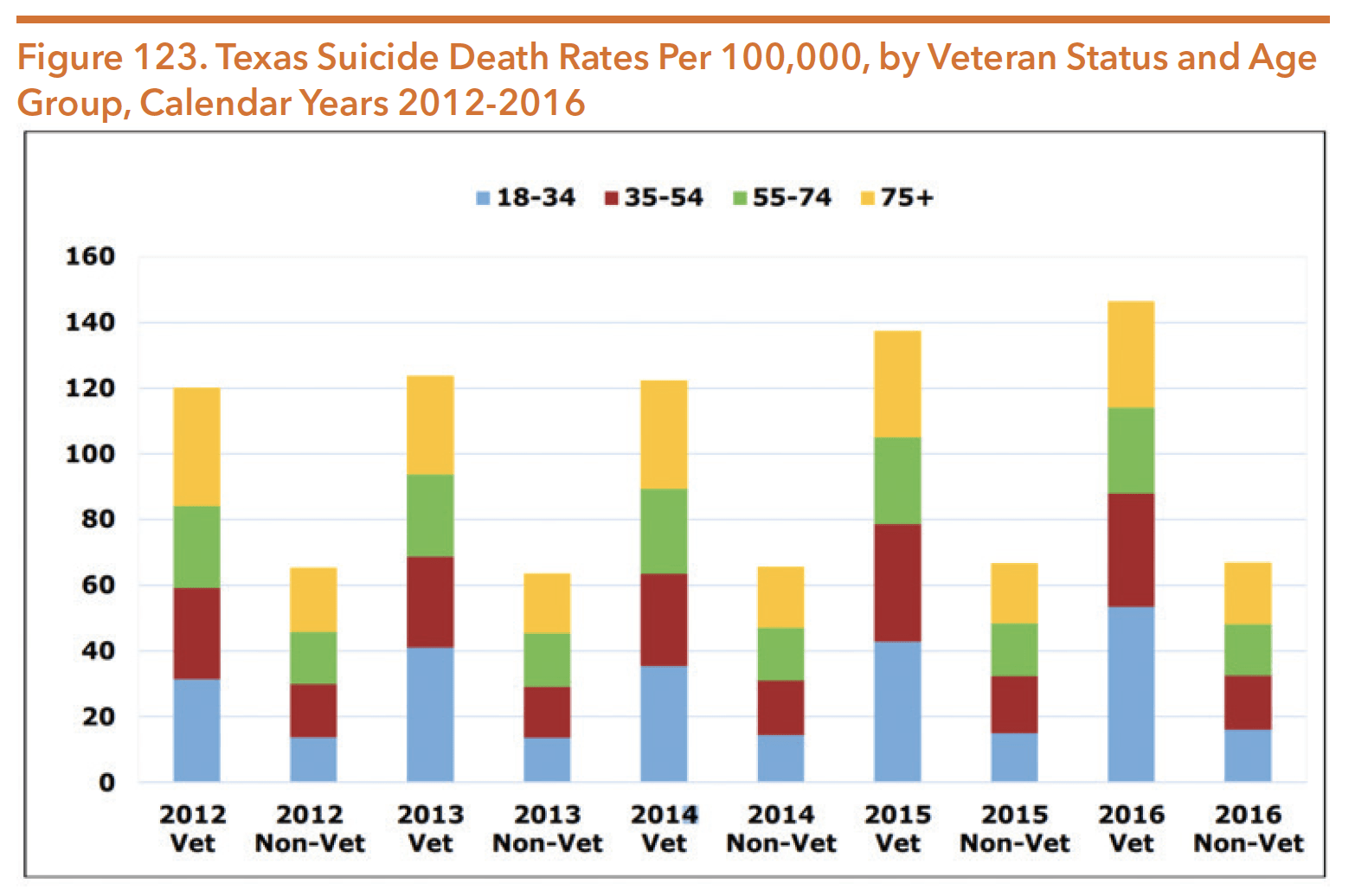

Veteran Suicides

The veteran population continues to be at particular risk of suicide compared to the general population. Figure 122 reflects the upward trend of veteran suicides in Texas by gender, from 2012 to 2016. Male suicide rates were disproportionately higher than that of females, although both saw a slightly increased rate over the 4 years. Of the 496 Texas veteran suicide deaths in 2017, over 95 percent were by males. Figure 123 compares veteran and non-veteran suicide rates and breaks them down by age. The results show that veterans are significantly more likely to die by suicide, across all age categories.

Source: Texas Health and Human Services Commission. (2019, September). Report on Short-Term Action Plan to Prevent Veteran Suicides. Retrieved from https://hhs.texas.gov/sites/default/files/documents/laws-regulations/reports-presentations/2019/short-term-veteran-suicide-plan-report-aug-2019.pdf

Source: Texas Health and Human Services Commission. (2019, September). Report on Short-Term Action Plan to Prevent Veteran Suicides. Retrieved from https://hhs.texas.gov/sites/default/files/documents/laws-regulations/reports-presentations/2019/short-term-veteran-suicide-plan-report-aug-2019.pdf

Access to firearms is the number one cause of veteran suicide death in Texas. In 2017, the gun suicide death rate for Texas veterans was over 20 percent higher than the total Texas population’s rate, and over 27 percent higher than the national average. Ranked by type of lethal means used in Texas veteran suicides, firearms were at 78 percent, suffocation at 12.5 percent, poisoning at 6 percent, and other means at 3.4 percent. A 2007-2014 study from the Annals of Internal Medicine showed that although 8.5 percent of suicide attempts are fatal, firearms are the most lethal method of suicide with a mortality rate of 89.6 percent. Access to lethal means therefore plays a significant determinant in the fatality rates of suicide attempts.

As part of SB 578 (85th, Lucio/ Blanco), HHSC issued a report in September 2019 on the Short-Term Action Plan to Prevent Veteran Suicide. Implementation of goals must be achieved by September 2021, and will focus on:

- Raising awareness among providers of the gaps in healthcare for service members, veterans, and families (SMVFs) which must be addressed to prevent suicide;

- Promoting the use of evidence-based and best practices regarding suicide prevention efforts for the SMVF population; and

- Normalizing safety seeking behavior.

Long-term recommendations for statutory, administrative, and budget-related policy initiatives and reforms will be completed by September 2021. Implementation of these goals must be achieved by September 2027.

VA Behavioral Health Services

Nationally, veterans’ health care services are administered on a regional level by a system of 23 veterans integrated service networks (VISNs), each containing a hierarchy of medical centers, on-site outpatient clinics, community-based outpatient clinics, and vet centers, which provide counseling, outreach, and referral services to help veterans adjust to life post-combat. Texas is primarily supported by VISN 17: VA Heart of Texas Health Care Network. In addition, VISN 16 serves areas of East Texas and VISN 19 serves parts of North Texas. For more information on each VISN, see https://www.va.gov/directory/guide/map.asp?dnum=1.

TVC does not directly operate or provide behavioral health services to veterans; instead, it links veterans to these services through their claims representation and counseling programs described above. There is a wide array of VA settings that provide both inpatient and outpatient behavioral health services, including primary care clinics, general and specialty outpatient mental health clinics, residential care facilities, and community living centers. Services and programs include:

- Specialized PTSD services;

- Psychosocial rehabilitation and recovery services;

- Suicide prevention programs;

- Evidence-based psychotherapy programs; and

- Substance use services.

The VA also provides behavioral health services for family members and survivors of active duty military personnel and veterans. Additionally, 300 Vet Centers nationwide provide psychological counseling for war-related trauma and other services such as outreach, case management, and social services referrals. Vet Centers served a total of 298,576 veterans, service members, and military families in FY 2018 and provided over 1.9 million no-cost visits for readjustment counseling. The latest report on VA health care utilization by recent veterans reported a total 9.8 million veterans (49 percent) used at least one VA benefit or service in FY 2017.

For a comprehensive description of federal benefits and services available to veterans, family members and survivors, visit http://www.va.gov/opa/publications/benefits_book.asp.

Veterans Mental Health Program and Other Supports

The Veterans Mental Health Program (VMHP) provides several services for veterans, including: Military Cultural Competency training for licensed mental health professionals, veteran mental health awareness training for community-based organizations and faith-based organizations, and programs for justice-involved veterans through engagement, training, and cooperation with justice system agencies.

The Military Veteran Peer Network is an affiliation of veterans and family members who actively identify and advocate for community resources for veterans and provide peer counseling services. Peer group leaders are trained in peer support and mental health awareness and establish peer group meetings in their communities. As of July 2020, the Military Veteran Peer Network website listed 37 available Peer Service Coordinators, which can be found here: https://www.milvetpeer.net/page/custompage_map.

“No one is better prepared to speak with a veteran about her experiences than another veteran, a peer.” – Military Veteran Peer Network

The Veterans Crisis Line

The Veterans Crisis Line (VCL) is a resource available during mental health crises, including suicide crises. VCL can be accessed by veterans, their families, and/or friends via telephone, text, or online chat to be connected with a trained VA responder. According to a January 2019 report, since its launch in 2007 the VCL had answered over 3.8 million calls and initiated the dispatch of emergency services to callers in imminent crisis over 112,000 times. The VCL anonymous online chat service, added in 2009, had engaged in more than 439,000 online chats. In November 2011, the VCL introduced a text messaging service to provide another way for veterans to connect through a personal cell phone or smart phone with confidential, round-the-clock support. Since that time it had responded to more than 108,000 texts. Over 640,000 referrals had been sent to local VA Suicide Prevention Coordinators to ensure the continuity of care of veterans. On a daily basis in FY 2018, the VCL received an average of 1,766 calls, 203 chats, and 74 texts. They also dispatched emergency services for imminent danger an average of 80 times per day.

TexVet

TexVet, a joint initiative by the Texas A&M Health Science Center and HHSC, is a network of health providers, community organizations, and volunteers who are committed to providing SMVFs with referrals and information to successfully access services. TexVet has initiated a “No Wrong Door” policy for the veteran community through its network and event-based activities, ensuring that veterans are properly connected to the services that they need by knowledgeable partners across the state. For more information, visit: http://texvet.org.

Specialty Courts

Left untreated, mental health and substance use conditions may lead to involvement in the criminal justice system. Under the typical criminal justice process, a veteran facing charges is assigned to a judge who may be unfamiliar with the unique challenges faced by returning veterans, such as traumatic brain injury, PTSD, depression, and substance use issues. Alternatively, a judge sitting in a specialty veteran’s court may have a better understanding of the mental health conditions and veteran-specific struggles that can increase risks for criminal behavior. The judge may also be more familiar with the range of community-based services and benefits available to veterans, and might include case managers and court clerks with military experience or familiarity working with veterans in the process. Thus, veteran’s courts may be more capable of diverting veterans from the criminal justice system and instead linking them and their families to benefits, services, and supports.

The first veteran’s court in Texas, located in Harris County, began accepting cases in 2009. As of September 2019, there were veteran’s courts operating throughout the state in the following 50 counties:

- Angelina

- Bell

- Bexar

- Bowie

- Brazoria

- Brazos

- Burnet

- Caldwell

- Cameron

- Cass

- Collin

- Comal

- Dallas

- Denton

- El Paso

- Fannin

- Fort Bend

- Galveston

- Grayson

- Gregg

- Guadalupe

- Harris

- Hays

- Hidalgo

- Hill

- Hutchinson

- Jefferson

- Jim Wells

- Kaufman

- Kerr

- Liberty

- Lubbock

- McLennan

- Midland

- Montgomery

- Nueces

- Potter

- Rockwall

- Rusk

- Smith

- Tarrant

- Titus

- Tom Green

- Travis

- Tribal

- Uvalde

- Val Verde

- Victoria

- Webb

- Williamson

Women Veterans

Women are the fastest growing population of veterans and are projected to make up 15 percent of all living veterans by 2035. Women veterans are more likely than women non-veterans to die by suicide and more likely to do so with a firearm. They are at a higher risk for exposure to sexual assault or harassment and are more likely than men to blame themselves for traumatic experiences. The VA has embarked on efforts to understand how to better serve woman veterans. In the general population, women are over twice as likely to develop PTSD as men. A 2015 study found that the risk of PTSD for men and women veterans is not significantly different after experiencing combat. However, women veterans are more likely to have lower incomes, lack private insurance, and have poorer health.

While women veterans are less likely than non-veterans to experience poverty, about 10 percent had incomes below the poverty level in 2015. VA healthcare statistics concluding in March 2014 showed that 54.8 percent of women veterans who served after September 11, 2001 had accessed VA health services. Because of their heightened risk for having experienced things like military sexual trauma, homelessness and financial stress, it is important that health care, including mental health and substance use services, support services, and transitional resources continue to be increasingly responsive to the needs of women veterans. Visit https://www.tvc.texas.gov/women-veterans/ for more information on other initiatives serving women veterans.

Health and Human Services Commission Veterans Services

HHSC collaborates with TVC on several initiatives to improve outcomes for veterans. HHSC is a member of the Texas Coordinating Council for Veteran Services administered through TVC, and TVC participates on the HHSC Statewide Behavioral Health Coordinating Council.

HHSC administers the Texas Veterans + Family Alliance Grant Program authorized in 2015 through SB 55 (84th, Nelson/King) and the Mental Health Program for Veterans established by the 81st Texas Legislature. In 2018, HHSC awarded 20 grants through the program. Grantees secured a total of $10 million to match $10 million in state general revenue funding. The grants will serve almost 20,000 veterans and their families, helping them to receive expanded access to mental health treatments and services.

HHSC also runs the Mental Health Program for Veterans, which allows peer-to-peer counseling services for veterans. In FY 2019, 133,144 peer services were delivered to SMVFs. Additionally, HHSC and TVC trained 5,552 peers, held 374 counseling sessions, and coordinated 33,669 services for justice-involved veterans and their families. The agency contracts with 39 LMHAs to provide these peer services. A total of $5 million was allocated in FY 2019 to operate the program, with $1.04 million for TVC to provide trainings and coordinate services for justice-involved veterans.

The Texas Department of Family and Protective Service’s Prevention and Early Intervention Division offers grants for their SMVF Program, which was established by HB 19 in the 84th Texas Legislature as an expansion of the Military Families and Veterans Pilot Prevention Program (MFVPP). This community-based initiative is meant to enhance coordination of community services to veterans with children. The program aims to improve child welfare and early education amongst other services. As of January 2020, Bell, Bexar, and El Paso counties all had community providers receiving MFVPP grants. The next solicitation will provide $1.6 million each year for 5 years.

Another major veterans initiative of HHSC is the Texas Veterans App. This is a free smartphone application that offers access to the following:

- Crisis intervention services through the Veterans Crisis Line

- Services for women veterans

- Local veterans and veteran service organizations

- Texas Veterans Hotline

- Texas Veterans Portal

Texas Veterans Hazlewood Act

The Texas Veterans Hazlewood Act offers eligible Texas veterans, their spouses, and their dependent children tuition exemption for up to 150 hours of college credits. This includes most fees charged at public institutions of higher education in Texas, but does not cover living expenses, books, or supply costs. There have been repeated attempts to drastically alter the Hazlewood Act through legislative funding changes, but those efforts have not been successful. More information on the Hazlewood Act is available at https://www.tvc.texas.gov/education/hazlewood-act/.