*Note: If you find the text on some of the images blurry or hard to read, right-clicking the image and then selecting “open image in new tab” may improve the issue.

Policy Concerns

- Impacts of COVID-19 on TJJD operations and on the mental health of youth in state custody;

- Diverting youth with behavioral health needs away from secure confinement;

- facilities and into their home communities with services and supports;

- Addressing the behavioral health needs of youth in their communities;

- Assessing the negative impacts of detaining youth in adult correctional facilities, including

- adjusting policies to change the upper and lower age limits of juvenile court jurisdiction based on the science of adolescent development;

- Addressing the school-to-prison pipeline and the disproportionality for youth of

- color and youth with special education needs;

- Ensuring strong oversight by the Office of the Independent Ombudsman at a time

- of significant systems change within the Texas Juvenile Justice Department;

- Assessing and sharing outcomes for state secure facilities and community

- interventions (e.g., recidivism, rehabilitation); and

- Continue to reduce the number of incarcerated youths in secure confinement facilities.

Fast Facts

- Almost two million youth are arrested in the U.S. every year. Of these youth, 70 percent have a mental health condition.

- Very few of the youth involved in the justice system are arrested for serious offenses like aggravated assault, robbery, rape or murder (under 3,000 out of almost 50,000 arrests in 2016).

- Re-arrest rates of youth are as high as 75 percent within three years after confinement within a juvenile justice facility.

- From September 2019 through March 2020, there were 792 youth in institutions, 87 youth in halfway houses, and 80 youth in contract residential placements. This is a total of 959 youth in the Texas juvenile system, which represents a 12.4 percent decrease from the 1,100 totals in FY 2019 through March.

- In FY 2018, the Legislative Budget Board estimated that youth in residential facilities cost $479.56 per day, youth on parole cost $41.07 per day, and youth on probation cost $13.55 per day.

- Texas has 45 pre-adjudication facilities operated at the county level. Seventeen of these facilities offer programs for youth with mental health conditions, and 13 provide programs for youth with substance use conditions.

- Texas has 35 post-adjudication facilities operated at the county level. Twenty-nine of these facilities offer programs for youth with mental health conditions, and 31 provide programs for youth with substance use conditions.

- In FY 2018, counties funded 74 percent of juvenile probation services, while the state funded 25 percent and the federal government provided only 1 percent of total funding.

TJJD Acronyms

- ACEs – Adverse Childhood Experiences LBB – Legislative Budget Board

- ART – Aggression Replacement Therapy MRTC – McLennan Residential Treatment Center

- BISQ – Brain Injury Screening Questionnaire OMHSE – Office of Minority Health Statistics and Engagement

- CEDD – Center for Elimination of Disproportionality and Disparities

- PAWS – Pairing Achievement with Services

- CINS – Conduct Indicating Need for Supervision PTSD – Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

- COG – Capital Offender Group

- CRCG – Community Resource Coordination Group SJPOs – Specialized Juvenile probation Officers

- CSG – Council of State Governments SNDP – Special Needs Diversionary Program

- CSU – Crisis Stabilization Unit TBI – Traumatic Brain Injury

- CSVOTP – Capital and Serious Violent Offender Program

- TCOOMMI – Texas Correctional Office for Offenders with Medical and Mental Impairments

- DFPS – Department of Family and Protective Services TEA – Texas Education Agency

- FEDI – Front End Diversion Initiative TJJD – Texas Juvenile Justice Department

- IO – Independent Ombudsman VOP – Violent Offender Program

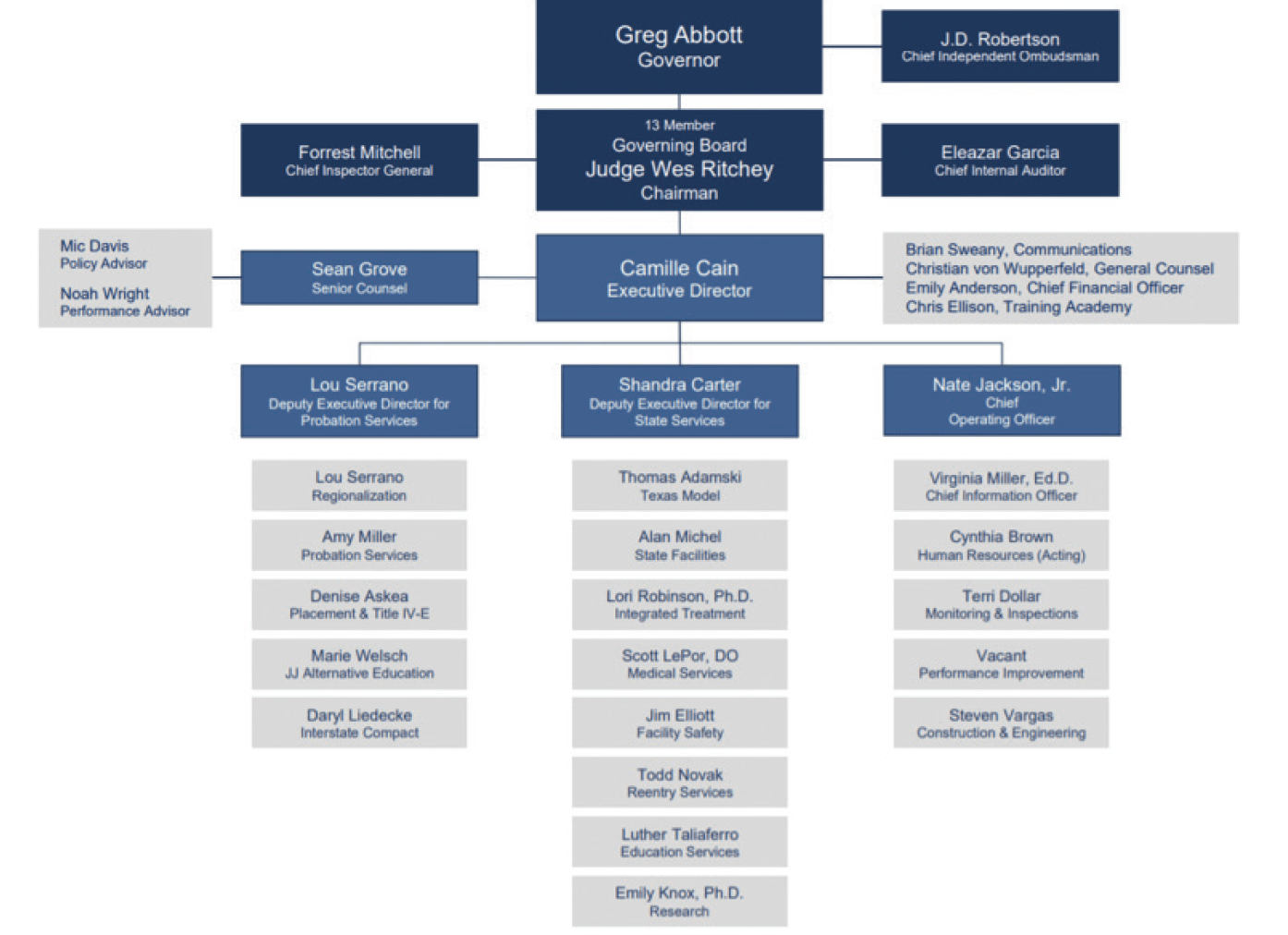

Organizational Chart

Source: Texas Juvenile Justice Department (September 2019). Retrieved from: https://www2.tjjd.texas.gov/docs/TJJDOrgChart.pdf

Overview

Unfortunately, the first contact for some children or youth with an emotional or substance use problem is a police officer, rather than a mental health professional. The initial purpose of the juvenile justice system was to act as a substitute parent; the system’s sole purpose was to help youth onto the right path, diverting them from later involvement in the adult criminal justice system. Over time, the system changed from the substitute parent role into an adversarial relationship like the adult criminal justice system.

Texas’s juvenile justice system includes the Texas Juvenile Justice Department (TJJD) and local juvenile probation departments throughout the state. These agencies work together to provide services designed to rehabilitate youth between 10 and 17 years old who engage in delinquent conduct.

SB 653 (82nd, Whitmire/Madden) created the TJJD in 2011. The agency began operations in December 2011 and the existing Texas Juvenile Probation Commission (TJPC) and Texas Youth Commission were abolished. TJJD is charged with “increasing the proportion of youth in local custody, rather than committed to state lockups.” The department’s ultimate goal is to prevent a juvenile’s entrance into the adult criminal justice system by providing treatment plans tailored to each child’s unique strengths and needs. TJJD provides oversight and funding to local juvenile probation departments across Texas and operates six secure state facilities for youth.

Changing Environment

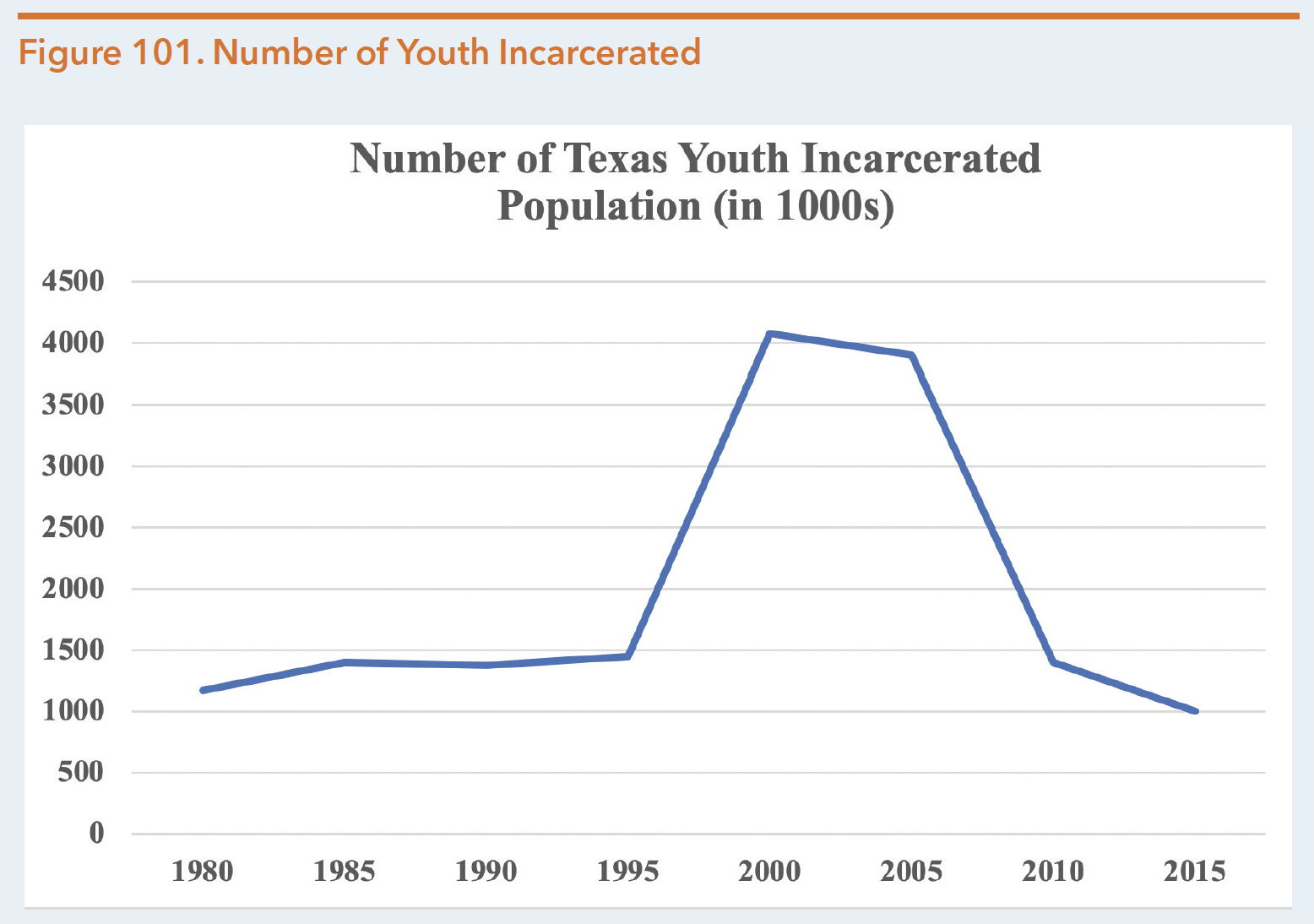

The Texas Legislature prioritized efforts to reduce youth incarceration rates in 2017, successfully decreasing the number of youth in secure state juvenile facilities. Statewide efforts to reduce youth incarceration has brought the number of youth incarcerations below 1,000 for the first time since the 1980s. In April 2018, the number of youth in TJJD fell below 900 for the first time in decades.

The figure below illustrates Texas’s state secure juvenile facility population between 1980 and 2017.

Source: McGaughy, L. (April 6, 2018). The number of Texas kids behind bars is suddenly at its lowest point in decades. Dallas Morning News. Retrieved from: https://www.dallasnews.com/news/crime/2018/04/06/the-number-of-texas-kids-behind-bars-is-suddenly-at-its-lowest-point-in-decades/

Chair of the Senate Criminal Justice Committee, Senator John Whitmire requested the Council of State Governments Justice Center (CSG) analyze the impact of those reform efforts. In 2015, the CSG released key findings, including: (1) youth confined in state-run facilities are two times more likely to be re-incarcerated within five years of release than youth sentenced to county-level probation, and (2) while reforms have benefited state and county-level juvenile justice systems, Texas can do more to decrease recidivism rates among justice-involved youth. CSG researchers recommended that TJJD and county probation departments concentrate their interventions on youth with the highest risk to reoffend and minimize involvement with low-risk youth. In late 2017, confirmed incidents of staff abusing youth at one of the remaining five TJJD facilities became public news. As a result, Governor Greg Abbott replaced the TJJD executive director, board chair, and the Independent Ombudsman positions. In June 2018, the new TJJD executive director Camille Cain submitted a letter to Governor Abbott with proposed short-term solutions and long-term goals for the agency. The short-term goal was stabilizing agency operations by improving supervision ratios (both by reducing the youth population and increasing the number of employees), improving safety, and adjusting training. Later that month, TJJD approved a strategic plan for 2019-23 detailing the future direction of the agency. More detailed information on the strategic plan can be found later in this section.

MAJOR LEGISLATION FROM THE 86TH LEGISLATURE

During the 86th legislative session, approximately 25 new bills were filed relating to juveniles or referred to the House Committee on Juvenile Justice & Family Issues. Five made it through both chambers and were signed into law, while three others made it, but were vetoed by the governor. In the Senate, eleven bills were filed, with three being signed into law. Legislation described below contains juvenile-related laws generally and is not an exhaustive account of juvenile justices and mental health legislation.

Juvenile Justice Bills Signed Into Law

HB 601 – Reporting Requirements for Persons Suspected to Have a Mental Illness or IDD

HB 601 (86th, Price/Zaffirini) is highlighted in the TCJC section and also applies to juveniles. HB 601 requires development of a written report assessing the youth’s mental health status to strengthen front-end mental health need identification of all persons entering criminal justice settings. In addition to adult reporting, examination on the issue of fitness to proceed with juvenile court proceedings must be by an expert appointed under Chapter 51 of the Texas Family Code.

Effective September 1, 2019, the legislation required a copy of any mental health records, screening reports, or similar information to accompany a youth that may be transferred to a Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) facility. It also mandates that youth who may have an intellectual disability also be assessed and that information be included in the report.

HB 1760 – Confidentiality, Sharing, Sealing, and Destruction of Juvenile Records

HB 1760 (86th, White/Wu) amends previous laws relating to juvenile records. It expands allowance of TJJD facility records disclosure to:

- An individual or entity referral for treatment or services and assisting in transition from release or discharge from a juvenile facility to the community;

- A prosecuting attorney;

- A parent or guardian with whom child will reside; and

- A government agency or court for administrative or legal proceeding with identifiable information redacted.

Effective September 1, 2019, the legislation also prohibits an individual or entity receiving confidential information from re-disclosing information.

HB 2229 – Relating to a Report of Information Concerning Juveniles in TJJD

In the 85th legislative session, HB 1521 (85th, White/Whitmire) and HB 932 (85th, Johnson/West) required the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS) to share information with TJJD. The bills also required TJJD, DFPS, and local juvenile probation departments to collect and share data, including how many youth in the juvenile justice system have ever been in foster care.

Building on reports indicating many youth involved in the foster care system would later enter a federal or state correctional system, the Texas 86th legislature took further steps to address this issue with additional requirements for TJJD to collect certain data for a child in TJJD custody. Data is now collected for purposes of assisting the legislature, advocates, and TJJD in altering, targeting, and increasing services to prevent foster youth from entering the juvenile justice system.

H.B. 2229 (86th, Johnson/Whitmire) requires TJJD to submit a report to each member of the legislature not later than January 31 of each evennumbered year. Previously, this report was made to the governor, the lieutenant governor, the speaker of the house of representatives, and each standing committee having primary jurisdiction over TJJD. The legislation also requires TJJD to make the report publicly available on TJJD’s website. The bill was effective immediately upon passage.

HB 2737 – Relating to Judicial Guidance Related to Child Protective Services Cases and Juvenile Cases

HB 2737 (86th, Wu/Johnson) directs the Texas Supreme Court, in coordination with the Supreme Court of Texas Permanent Judicial Commission for Children, Youth and Families, to annually provide guidance to judges who preside over:

- Child protection cases including placements, changes in placement, and termination of parental rights; and

- Juvenile justice cases including placements for children with mental health concerns, releases, certification of standing trial as adults, commitment to TJJD, and a child’s appearance before court including use of restraints and clothing worn during the proceeding.

HB 3688 – Relating to the Apprehension of a Child after Escape from a Secure Juvenile Facility or Violation of Conditions of Release Under Supervision

After concerns raised regarding the limited authority of some peace officers responding to a directive issued from TJJD, HB 3688 (86th, White/Perry), was aimed to address the issue. Effective September 1, 2019, the bill extends authority to certain peace officers to apprehend juvenile offenders in TJJD care that have either escaped secure confinement or violated the conditions of their release.

The bill amends the Human Resources Code to include a special investigator among the persons authorized to arrest without a warrant a child who has been committed to TJJD. The list of peace officers now includes a sheriff, deputy sheriff, constable, special investigator, or any other peace officer (police) who is authorized to, without a warrant, arrest the youth.

SB 562 – Relating to Criminal or Juvenile Procedures Regarding Persons or Youth Who have, or may have, a Mental Illness or IDD

Previously when a person or youth with a mental illness was charged with a violent or sexual crime and found incompetent to stand trial or not guilty by reason of insanity (NGRI), state law required judges to send them to a maximum-security unit (MSU), even when that placement was not appropriate. The Health and Human Services Commission’s (HHSC) Dangerousness Review Board would then conduct an assessment of the defendant to determine whether an MSU was appropriate. Due to the inadequate number of MSU beds available statewide, a person or youth with a mental illness could be left waiting in custody without adequate treatment and without timely progress in their case.

Many defendants did not meet the clinical standard for dangerousness despite the seriousness of the alleged offense. It was inefficient to have a person in custody for months without proper mental health treatment waiting to occupy an MSU bed when it was not an appropriate placement for them.

Immediately effective on June 14, 2019, SB 562 (86th, Zaffirini/Price) ensures that the best location for a person or youth to receive competency restoration would be determined at the outset, rather than waiting for the defendant to be sent to an MSU unit first before determining the adequate treatment setting. The legislation will reduce the MSU waiting list while reserving limited MSU beds for persons or youth who need those specialized beds. Persons committed to non-MSU facilities as a result of this new process should experience shorter wait times in custody and a more timely path to a state hospital or other treatment facility.

SB 1702 – Relating to the Powers and Duties of the Office of Independent Ombudsman for the Texas Juvenile Justice Department

SB 1702 (86th, Whitmire/Dutton) was filed to provide safeguards ensuring that juveniles remain in safe and secure facilities, while balancing the necessary security to facilitate an effective juvenile justice system. Previously, the TJJD independent ombudsman duties included oversight and inspection of facilities in which juveniles were housed within the juvenile justice system. Traditionally the ombudsman performed duties only at the five secure facilities located throughout Texas.

After TJJD’s independent ombudsman’s inspection and oversight of post-adjudication and contract facilities expired on January 1, 2019, concerns were raised with the potential gap in oversight, but SB 1702 alleviates those concerns and that potential gap has now been filled.

Effective on September 1, 2019, the independent ombudsman is able to provide necessary oversight at any facility where a juvenile might be housed, including post-adjudication probation facilities and contract facilities. The expanded authority will ensure the safety and security of all juveniles in the TJJD system.

SB 1887 – Relating to Jurisdiction over Certain Child Protection and Juvenile Matters Involving Juvenile Offenders

SB 1887 (86th, Huffman/Murr) amended previous laws relating to jurisdiction over certain child protection and juvenile matters involving juvenile offenders. Because youth can interact with both the child welfare and juvenile justice systems, various conflicts hindered courts and service providers. For example, conflicts between the juvenile justice and welfare systems would have contradictory court orders, conflicting treatment plans, duplication of services and hearings, higher placement costs, and a waste of limited resources.

Effective September 1, 2019, this bill allows juvenile courts to transfer or refer parts of cases to the children’s courts for youth involved in both the juvenile justice and child welfare systems and allows children’s courts to hear these cases.

Juvenile Justice Bills Vetoed by the Governor

HB 1771 (86th, Thierry/Huffman) – Relating to a prohibition on prosecuting or referring to juvenile court certain persons for certain conduct constituting the offense of prostitution and to the provision of services to those persons.

HB 1771 would have prevented the prosecution of individuals younger than 17 for certain prostitution offenses. This bill intended to prevent engagement in delinquent conduct, community supervision, arrests, or referrals to a juvenile court. Instead, the youth would have been returned to their parents or DFPS. The legislation would have directed law enforcement to use their best efforts to reunite the youth with a parent/guardian, and when all options had been exhausted, to contact a local service provider in consultation with the child sex trafficking prevention unit and the governor’s program for victims of child sex trafficking. The governor said the new law would have “unintended consequences” and could provide an incentive for human traffickers to exploit underage prostitutes.

HB 3195 – Relating to juveniles committed to the Texas Juvenile Justice Department and the transition of students from alternative education programs to regular classrooms

HB 3195 (86th, Wu/Whitmire) was filed to address concerns that TJJD lacks the flexibility to reduce the period of confinement for certain juvenile offenders who are sentenced to a residential program. The bill would have provided the flexibility for youth to be released early. The bill was vetoed, in part, because it would have removed the requirement that juvenile offenders participate in certain educational programs before being eligible for parole.

HB 3648 – Relating to the powers and duties of the office of independent ombudsman for the Texas Juvenile Justice Department

Filed as an administrative “clean up” bill to clarify language pertaining to the duties of TJJD’s independent ombudsman, HB 3648 (86th, Guillen/Whitmire) was vetoed because its goal had allegedly already been accomplished through SB 1702.

TJJD Funding

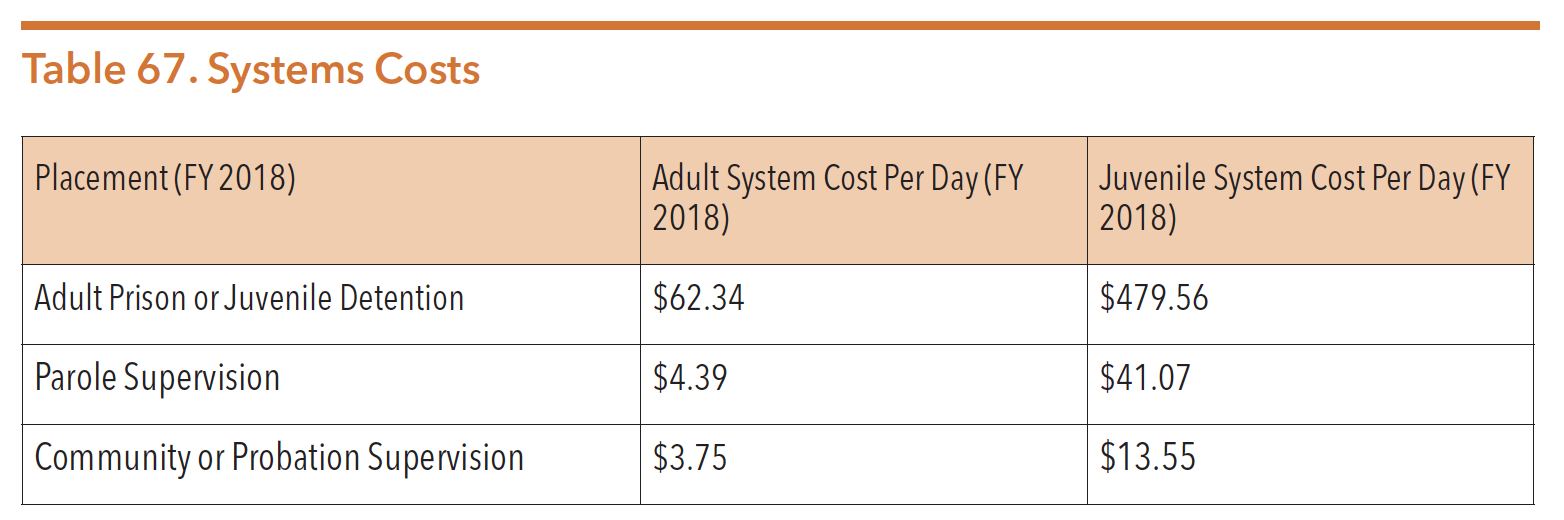

Cost Per Day: Juvenile System vs. Adult System

On February 29, 2020, there were 795 youth committed to six state secure facilities, 80 youth in halfway houses, and 98 youth in contact care facilities. In FY 2018, the Legislative Budget Board estimated that youth in residential facilities cost $479.56 per day. The table below illustrates the differences between the two systems in cost per day.

Source: Legislative Budget Board (February 5, 2019). Overview of Criminal and Juvenile Justice Correctional Population Projections, Recidivism Rates, and Costs Per Day. Page 12. http://www.lbb.state.tx.us/Documents/publications/presentation/5678_HAC_CJDA%20Overview.pdf. Accessed 7 Apr. 2020.

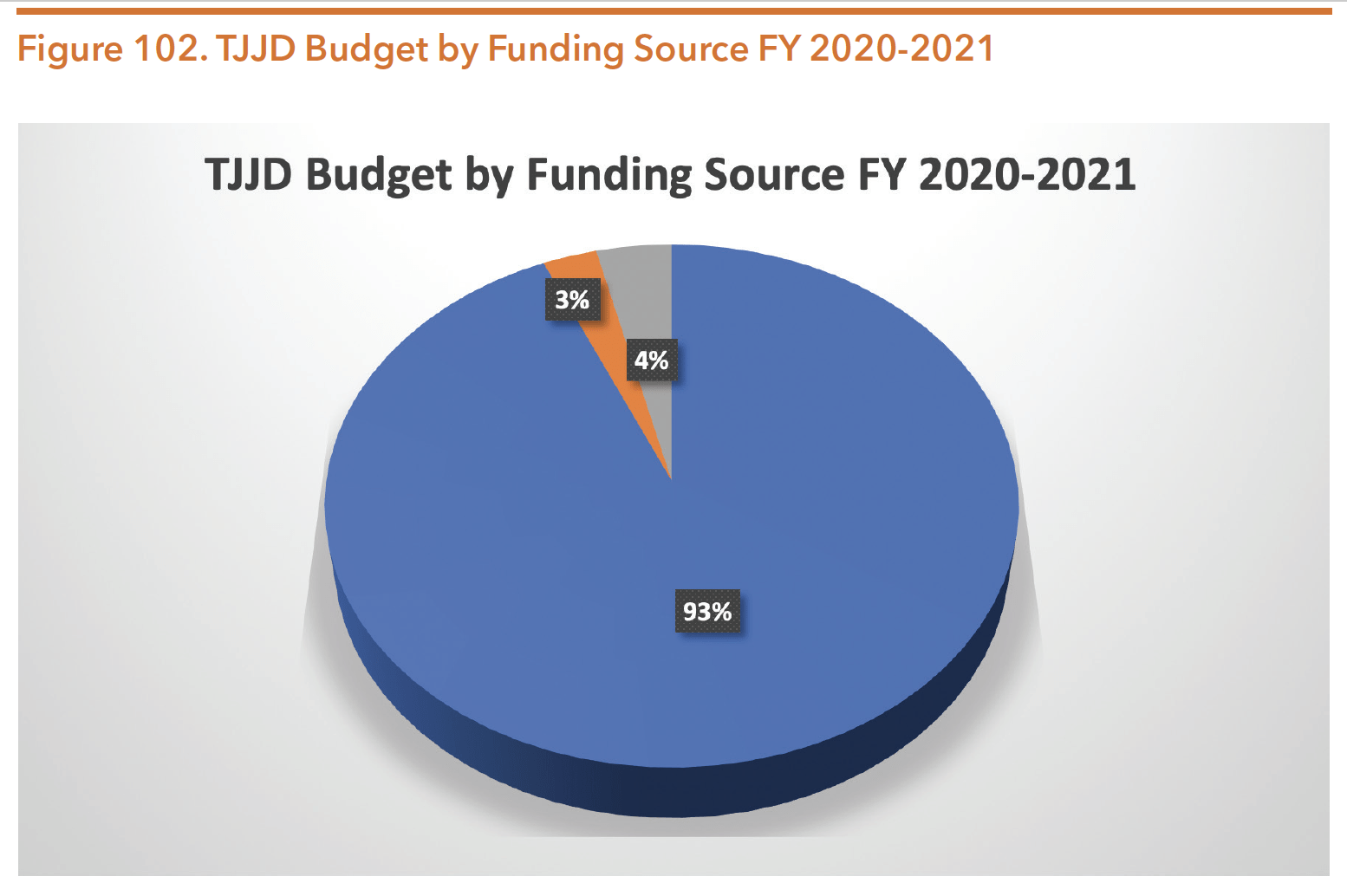

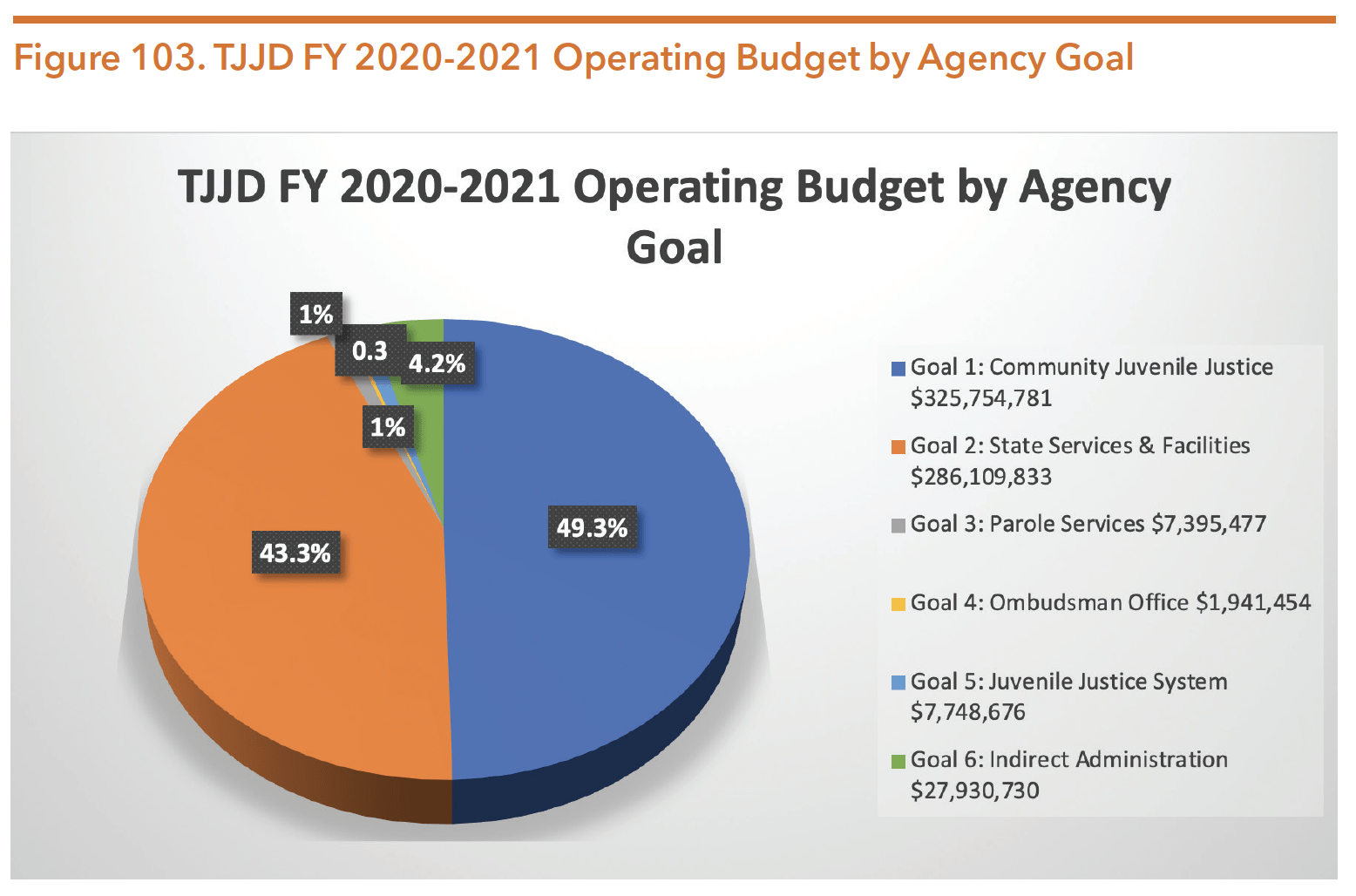

The total FY 2020/21 appropriation for TJJD for FY 2020-2021 was $656,880,951.49 The figure below breaks down TJJD’s budget by funding source and the following figure shows TJJD’s budget by agency goal.

Source: General Appropriations Act for the 2020-21 Biennium (August 2, 2019). Eighty-sixth Texas Legislature Regular Session, 2019. Text of Conference Committee Report on House Bill No. 1. https://www.lbb.state.tx.us/Documents/GAA/General_Appropriations_Act_2020_2021.pdf Accessed 7 Apr. 2020.

Source: General Appropriations Act for the 2020-21 Biennium (August 2, 2019). Eighty-sixth Texas Legislature Regular Session, 2019. Text of Conference Committee Report on House Bill No. 1. https://www.lbb.state.tx.us/Documents/GAA/General_Appropriations_Act_2020_2021.pdf. Accessed 7 Apr. 2020.

Many individuals in the juvenile justice system have experienced trauma and/or live with a mental health or substance use conditions. While it is difficult to cull all the resources devoted to mental health in the TJJD, below are budget strategies and riders specifically related to mental health treatment and services in the department as depicted in HB 1 (86th).

Strategy A.1.7 – Mental Health Services Grants $14,178,353 $14,178,351

Strategy B.1.7 – Psychiatric Care $942,670 $922,851

Strategy B.1.8 – Integrated Rehab Treatment $11,745,539 $11.740,740

Rider 28 – Mental Health Services Grants – Included in the amounts appropriated above in Strategy A.1.7, Mental Health Services Grants, is $14,178,353 in fiscal year 2020 and $14,178,351 in fiscal year 2021 to fund mental health services provided by local juvenile probation departments. Funds subject to this provision shall be used by local juvenile probation departments only for providing mental health services to juvenile offenders. Funds subject to this provision may not be utilized for administrative expenses of local juvenile probation departments nor may they be used to supplant local funding.

Rider 37 – Study on the Confinement of Children with Mental Illness or Intellectual Disabilities- Out of the funds appropriated above, the Juvenile Justice Department shall conduct a study to develop strategies to reduce the confinement of children with mental illness or intellectual disabilities. Not later than September 1, 2020, the department shall report the results of the study to the Governor, Lieutenant Governor, Speaker of the House, and each member of the Legislature.

Texas Juvenile Justice System

Recently, TJJD has actively reformed how the youth system works. Guided by the central principle of putting kids first, the agency has historically focused on safety and security to improve outcomes for youth. At the same time, TJJD funnels resources to probation departments, supporting models for youth with the most intense needs and implementing trauma-informed corrections across the state. Since January 2018, the main principles of developing Texas’s unique model of youth corrections have been to:

- Keep youth from engaging with the juvenile justice system if possible;

- Increase probation resources and preserve local control;

- Focus on the needs and risks of youth;

- Provide scalable, graduated options to meet youth and system needs;

- Commit to the shortest appropriate time period for youth to be in the system;

- Have youth stay as close to their communities whenever possible according to their best interests; and

- Infuse trauma-informed care throughout the system.

TJJD also partners with local juvenile justice systems across the state. At the county level, TJJD works with local juvenile boards and probation departments to enhance community-based programming, placements, and supervision. TJJD’s responsibilities in local counties include:

- Providing funding, technical assistance, and training to county justice officials;

- Establishing and overseeing standards of operation in county facilities;

- Analyzing and disseminating data to local justice boards and probation departments; and

- Facilitating communication between state and local leaders.

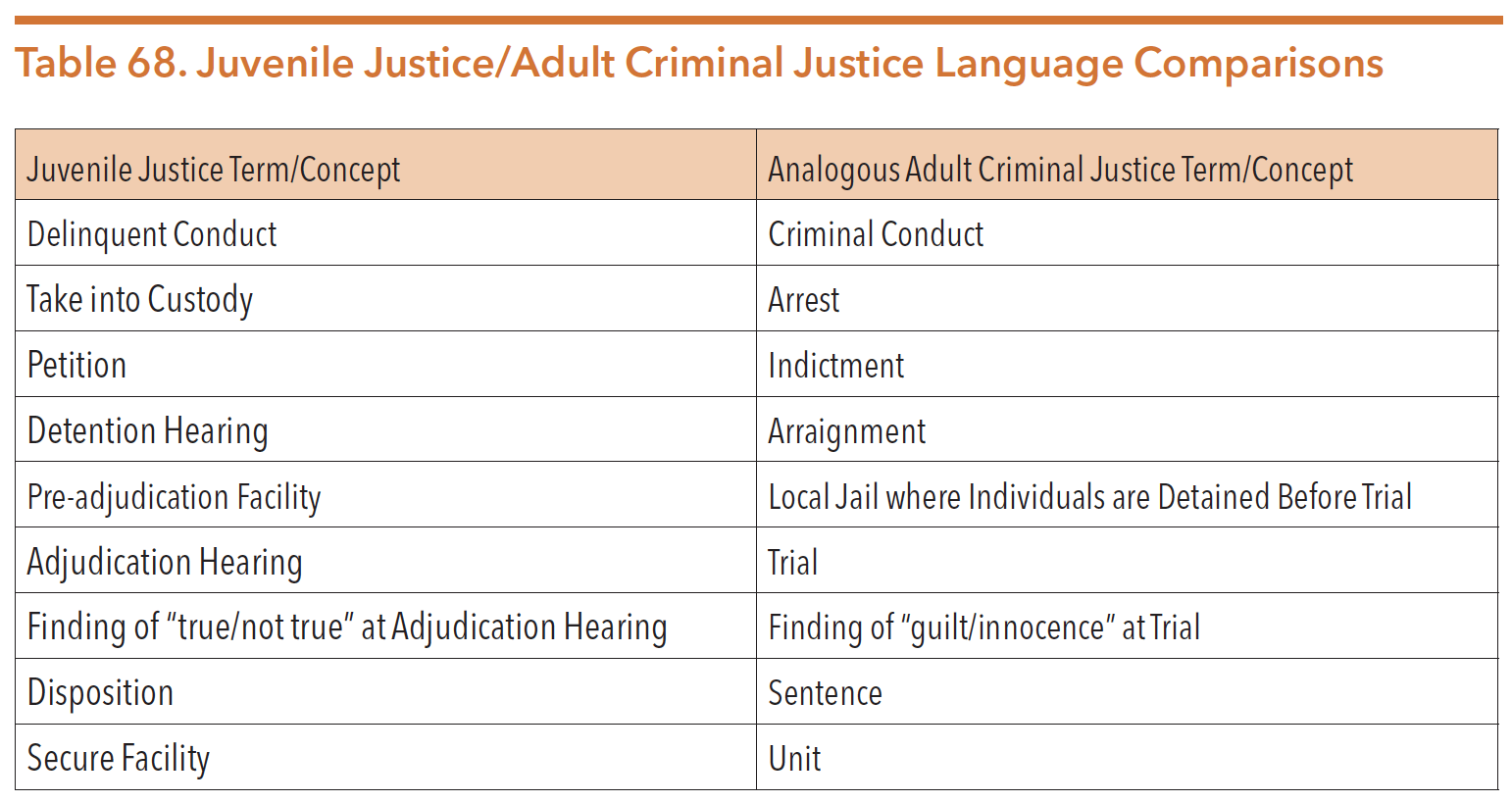

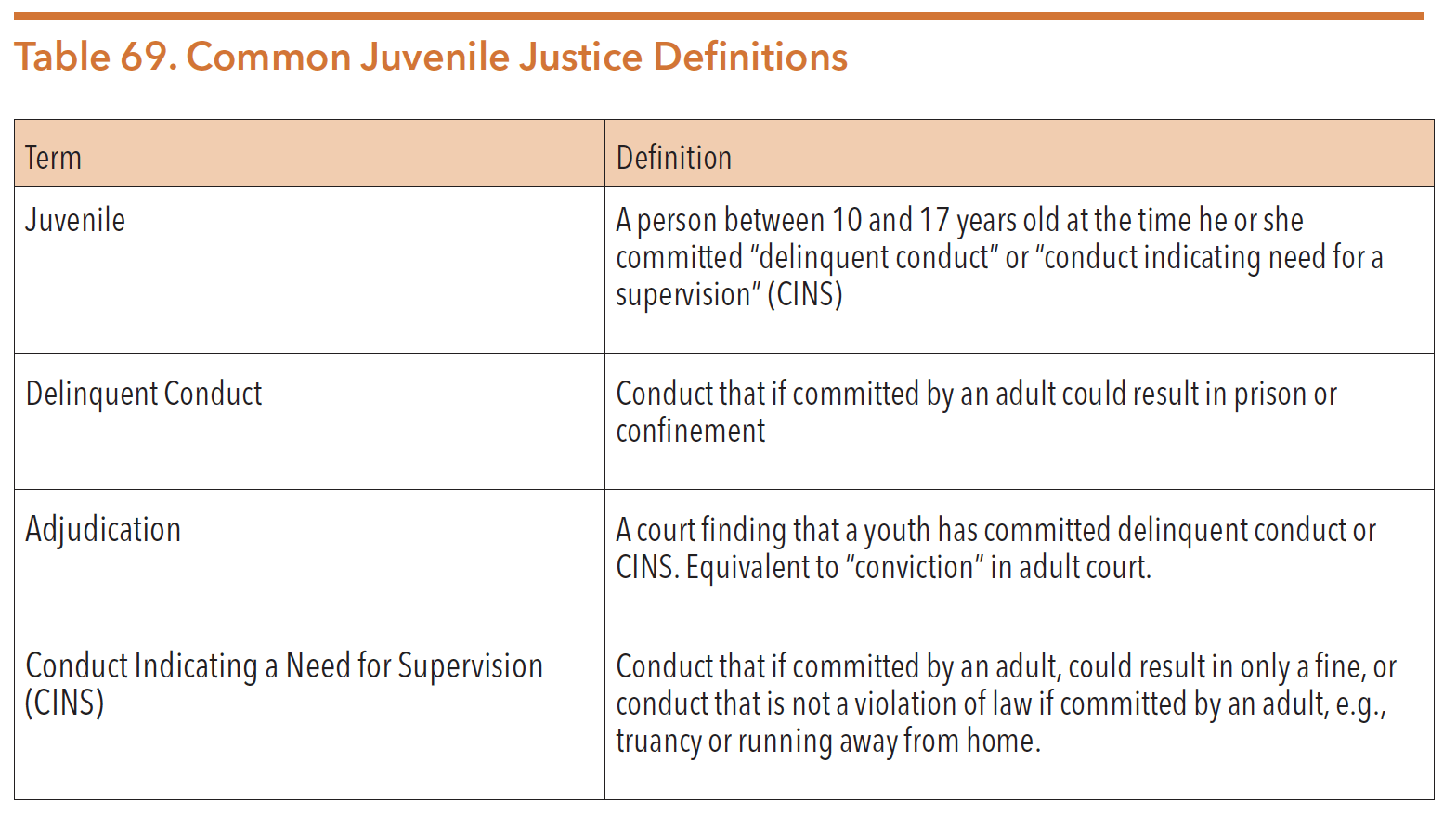

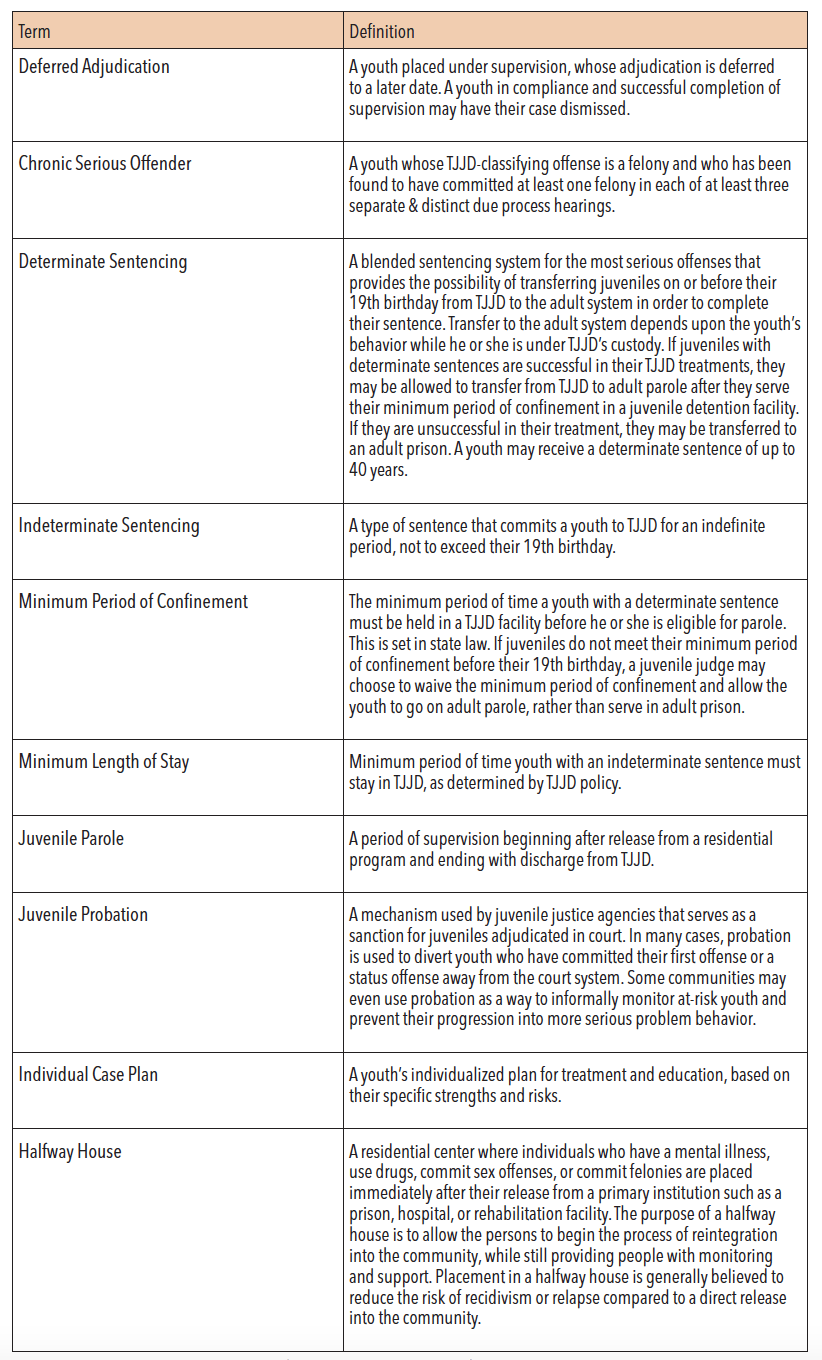

With an emphasis on rehabilitation, the juvenile system was designed to be a civil system rather than punitive like the adult criminal justice system. The tables below demonstrate the difference between the juvenile and adult systems, including a point of reference for parallel terms used in the two justice systems and common definitions for terms used in the juvenile system.

Source: Texas Juvenile Justice Department. (n.d.). Definitions for Common TJJD Terms & Acronyms. https://www2.tjjd.texas.gov/about/glossary.aspx. Accessed 8 Apr. 2020.

Source: Texas Juvenile Justice Department. (n.d.). Determining How Long Youth Stay in TJJD. https://www2.tjjd.texas.gov/about/how_class.aspx. Accessed 8 Apr. 2020.

For a full list of terms and definitions commonly used throughout TJJD, see: https://www2.tjjd.texas.gov/about/glossary.aspx.

TJJD BED CAPACITY ADJUSTMENTS

In August 2019, TJJD operating capacity decreased by 24 beds due to the closure of the Cottrell halfway house.

In June 2018, TJJD operating capacity decreased by 149 beds. This was due to the transfer of the ownership of the Corsicana facility to the City of Corsicana.

In September 2018 TJJD operating capacity decreased by 319 beds. This was due to the reduction in capacity at the Corsicana facility (49 beds), Giddings facility (46 beds), McLennan facility (120 beds), Ron Jackson I facility (16 beds halfway houses (40 beds), and contract residential placements (48 beds).

TJJD STRATEGIC PLAN

In June 2018, TJJD approved a new strategic plan for fiscal years 2019-23. The plan included four goals:

1. Improve current operations at secure facilities.

2. Develop and implement a fully trauma-informed system.

3. Improve cross-functional collaboration and local control.

4. Deliver the Texas Model across the state.

The Texas Model, as articulated in a plan issued shortly before the strategic plan, includes both principles for designing the juvenile justice system and principles for programmatic interventions.

System Principles:

- A focus on need and risk levels of youth;

- A graduated set of options to meet youth and system needs, which may change over time;

- A greater focus on a single juvenile justice system as a partnership between county juvenile probation departments and TJJD;

- A commitment to the shortest appropriate length of stay;

- Youth stay closer to their communities in every possible case;

- Keep youth from engaging far into the juvenile justice system if possible; and

- Provide for scalability to meet changing or emerging needs

Intervention Principles:

- A foundation in trauma-informed care;

- A treatment-rich environment and direct-care staff who reinforce treatment goals;

- An approach grounded in evidence-based practices; and

- Transparent plans between agency and youth to understand requirements and the consequences of their actions—both positive and negative—with strong accountability

HOW JUVENILES MOVE THROUGH THE JUVENILE JUSTICE SYSTEM

Texas youth who move through the entire juvenile justice system typically encounter these six major steps:

- Step One: Taken into custody by local law enforcement or referral to juvenile probation;

- Step Two: Disposition by a county juvenile court judge;

- Step Three: Fulfillment of a disposition (i.e., sentence) in a state-level facility (e.g., a detention center or halfway house), county-level facility, and/or in the community, depending upon the juvenile’s committing offense and judicial discretion;

- Step Four: Appraisal by the TJJD Release Review Panel (for youth committed to a secure state-level facility);

- Step Five: Completion of parole supervision; and

- Step Six: Discharge from TJJD.

Diversion from the juvenile justice system and to community-based services is possible before any of these steps. Diversion is increasingly a focus for all youth, particularly for youth with significant trauma histories and behavioral health needs.

For more information on diversion, see the “Local Criminal Justice Systems” section in the TDCJ chapter of this guide.

The following section will describe each of the six steps in greater detail.

STEP ONE: TAKEN INTO CUSTODY OR REFERRAL TO JUVENILE PROBATION

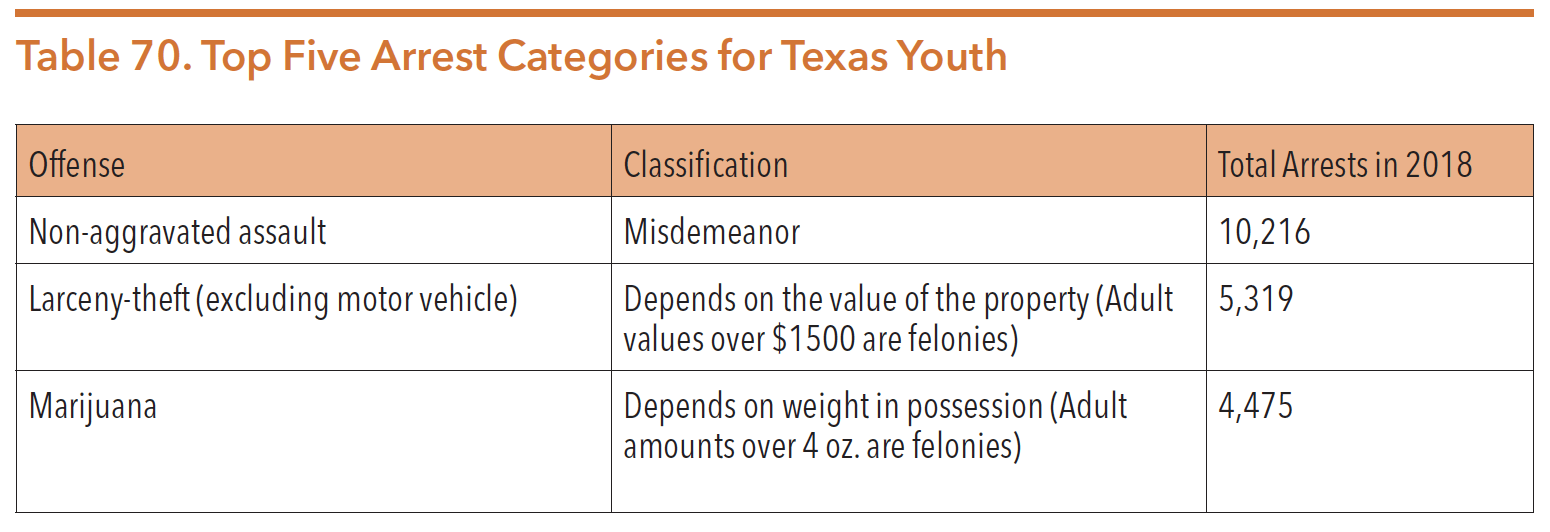

In 2018, law enforcement agencies in the U.S. made an estimated 728,280 arrests of persons under age 18. In 2018, Texas law enforcement officers made 41,208 juvenile arrests. The vast majority of juveniles who come into contact with the justice system commit low-level offenses. In Texas, 59 percent (24,388) of juvenile arrests were for nonviolent offenses such as larceny-theft, motor vehicle theft, running away from home, alcohol and drug violations, and violations of curfew and loitering laws. The table below shows the top five arrest categories with the most common offenses for which youths are taken into custody.

Source: Texas Department of Public Safety. 2018 Crime in Texas Report: Texas Arrest Data. Page 68. https://www.dps.texas.gov/crimereports/18/citCh9.pdf. Accessed 10 Apr. 2020.

Many Texas youth have mental health needs at the time of their arrest. A 2011 study of youths who were either at a TJJD facility or in a juvenile probation program found that 38 percent had a mental health condition or emotional disturbance.

Both TJJD and the court system have recognized that treating mental health conditions is critical to helping youth development, including getting an education in the community safely.

Youth with mental illness are three times more likely than their peers to be arrested before graduating high school. These youths are more likely to face official charges than others once they make contact with law enforcement, including the charges listed in the table above. Other youth become involved in the justice system without receiving a formal charge; they are routed to the justice system in order to receive treatment or to manage disruptive behaviors that result from unidentified mental health conditions.

In Texas, a peace officer that decides to take a youth into custody may:

- Transport the youth to an official juvenile processing office, where he or she may be kept for up to six hours;

- If believing the youth to be a truant, take the youth into custody for the purpose of returning him or her to the appropriate school campus if the school agrees to assume responsibility for the youth for the remainder of the day;

- Return the youth to a parent or other responsible adult; or

- If the youth is not released to a parent or guardian, transport the youth to the appropriate juvenile detention facility.

STEP TWO: JUVENILE COURTS, DISPOSITIONS, AND PLACEMENTS

Following an arrest, juveniles are taken to a county juvenile probation department for the intake and assessment process. Afterward, most youth are released to a parent or guardian as they await more information about their disposition. Other youth may be diverted away from the justice system and into community-based programs. Alternatively, their cases may be dismissed entirely. Youth who are not diverted or released to a caretaker must appear before a juvenile court judge within 48 hours of intake.

A juvenile court judge typically makes a determination on whether a youth’s case can be handled informally or if the youth must be placed under TJJD custody. For example, a juvenile court judge can allow the youth to remain in their community on a deferred prosecution.

Specialty courts serve a small number of youth by aiming to address the underlying causes of juvenile justice involvement. Specialty courts often operate as one piece of a larger continuum of diversion services for youth with behavioral health conditions. The most common specialty courts for juveniles are drug courts and mental health courts. Both types of courts utilize individual treatment plans, case management, and judicial supervision to link youth to treatment services in the community rather than place them in a secure facility.

Juvenile Drug and Mental Health Courts

As of April 2020, there were 336 juvenile drug courts nationwide, with 11 in Texas. Currently, Texas has five counties that operate juvenile mental health courts: Dallas, Denton, El Paso, Harris, and Jefferson. A 2011 evaluation of Texas specialty courts found that mental health courts are an effective alternative to placement in psychiatric hospitals and detention facilities because treatment-oriented court teams effectively address criminogenic risk factors, such as family poverty. In 2015, researchers also demonstrated that individuals who participate in juvenile mental health courts experience improved psychiatric outcomes, significantly fewer rearrests, and less re-convictions than their peers with similar criminal histories. Although the courts produce positive outcomes, recent data also show racial and gender disparities in access to this diversion strategy. Further, attempts to gather data on the number of youth who are served within these resource-intensive programs compared to those who could potentially benefit from such services, demonstrate the need for improved data collection and analysis among existing specialty court programs.

STEP THREE: FULFILLMENT OF A DISPOSITION

If a youth is adjudicated for delinquent conduct, the youth may be placed on probation or sent to detention in a county or state facility. Placements within a detention facility are reserved for high-risk youth who judges determine need intensive intervention. Since 2007, only juveniles who commit felonies are eligible for placement in state secure facilities, while youth who commit misdemeanors must be kept in county-level facilities or in their home communities. Youth who are adjudicated for certain serious offenses may receive a determinate sentence and possible transfer to adult prison depending on the youth’s behavior and progress while placed in a TJJD facility.

Between 2007 and 2018, TJJD relied more heavily on community-based interventions for youth, causing the average daily population within residential facilities to decrease by over 80 percent.

Admission into a TJJD secure facility is one of the most serious placements for a juvenile in Texas. However, Texas law also allows courts to certify youth who are over the age of 13 as adults and transfer them to the adult criminal justice system. In theory, juveniles who commit the most serious offenses, such as murder, may get sent to adult criminal court. In practice, data show that the primary difference between assignment to the juvenile or the adult system is the county of conviction, not the youth’s offense history. In a 2011 study, researchers found that court officials in six counties (Harris, Jefferson, Hidalgo, Nueces, Lubbock, and Potter) disproportionately chose to certify youth as adults, instead of giving juveniles determinate sentences. In 2017, Harris County certified 23 youth (and declined to certify 7 youth), a 39 percent decrease from 2016.

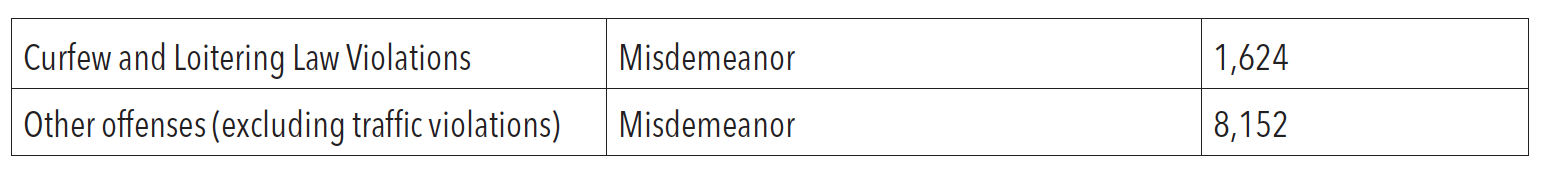

The table below shows the number of referrals and dispositions for youth involved in the juvenile justice system in FY 2017. For more information about secure placements and the behavioral health treatments available to youth within these placements, see the “Behavioral Health Services in State Secure Facilities” section of this chapter.

Sources: Texas Juvenile Justice Department. (December 2018). Annual Report to the Governor and Legislative Budget Board: Community Juvenile Justice Appropriations, Riders and Special Diversion Programs. Page 13. http://www.tjjd.texas.gov/index.php/doc-library/send/615-archive/1591-tjjd-annual-report-to-the-governor-and-legislative-budget-board-2018

Texas Juvenile Justice Department. (December 2019). Annual Report to the Governor and Legislative Budget Board: Community Juvenile Justice Appropriations, Riders and Special Diversion Programs. Page 13. http://www.tjjd.texas.gov/index.php/doc-library/send/338-reports-to-the-governor-and-legislative-budget-board/2285-tjjd-annual-report-to-the-governor-and-legislative-budget-board-2019

Note: The “formal referrals” data includes the total number of times youth were referred to juvenile probation departments. The “juveniles referred” data includes the total number of youth who were referred to probation. Because one juvenile can be referred to the department more than once, the “formal referrals” data point is greater than the “juveniles referred” data point.

STEP FOUR: APPRAISAL BY TJJD REVIEW PANEL

After juveniles with indeterminate sentences complete their minimum length of stay within a TJJD facility, officials on TJJD’s Release Review Panel assess each youth’s progress. The three-member panel examines the youth’s behavior, educational accomplishments, and response to behavioral health treatments to determine if the youth can be served safely in the community.

STEP FIVE: COMPLETION OF PAROLE SUPERVISION OR EXTENDED STAY IN TJJD FACILITY

The Release Review Panel may choose to release the youth into the community on parole or extend their stay within a TJJD facility. In FY 2018, the Release Review Panel extended juveniles’ stays within secure facilities 63.4 percent of the time. Within those extension decisions, about 13.2 percent of the juveniles had moderate mental health needs and about 26.8 percent had high substance use treatment needs.

Most youth paroled from a TJJD facility are supervised by a TJJD parole officer. There are 32 statewide parole officers located at offices in key population centers across Texas. In addition to in-person visitation, they also engage with some youth and families in rural and remote areas pre- and post- release through virtual visits via videoconferencing. A small proportion (roughly 9 percent) of youth are supervised through contracts with probation staff in rural juvenile probation departments; these probation officers will typically have a caseload of 2-3 youth paroled from TJJD as well as a traditional probation caseload. Some counties have enough youth to support officers solely dedicated to TJJD youth on parole.

TJJD parole officers are in the preliminary stages of being trained in Effective Practices in Community Supervision (EPICS), an evidence-based approach designed to shift supervisory interactions from a confrontational nature to a relationship-building approach grounded in fairness, trust, and an authoritative (not authoritarian) style.86 Using EPICS, each meeting between a parole officer and a youth includes four steps: check-in, review, intervention, and homework. Typical interventions are evidence-based and may be designed to develop motivational skills, problem-solving skills, or cognitive behavioral skills. TJJD reports that EPICS’ foundation of positive relationships is complementary to TJJD’s implementation of Trust-Based Relational Intervention.

STEP SIX: DISCHARGE FROM TJJD

When juveniles successfully complete their dispositions, TJDD may discharge them from custody. Juveniles are typically discharged when 1) they finish their treatment program, 2) they turn 19 and are no longer under TJJD’s jurisdiction, or 3) they received a determinate sentence and are transferred to the adult justice system in order to complete their sentence. Similar to justice-involved adults, justice-involved youth with mental health conditions often face challenges upon reentry, including stigma and discontinuity of care.

THE OFFICE OF THE INDEPENDENT OMBUDSMAN

In 2007, following highly publicized allegations of abuse within a state secure facility, the 80th Texas Legislature created the Office of the Independent Ombudsman as a separate state agency responsible for investigating, evaluating, and securing the rights of youth committed to TJJD. The independent ombudsman (IO) is responsible for investigating a variety of complaints including medical and mental health concerns, abuse allegations, and suicidal ideation and attempts.

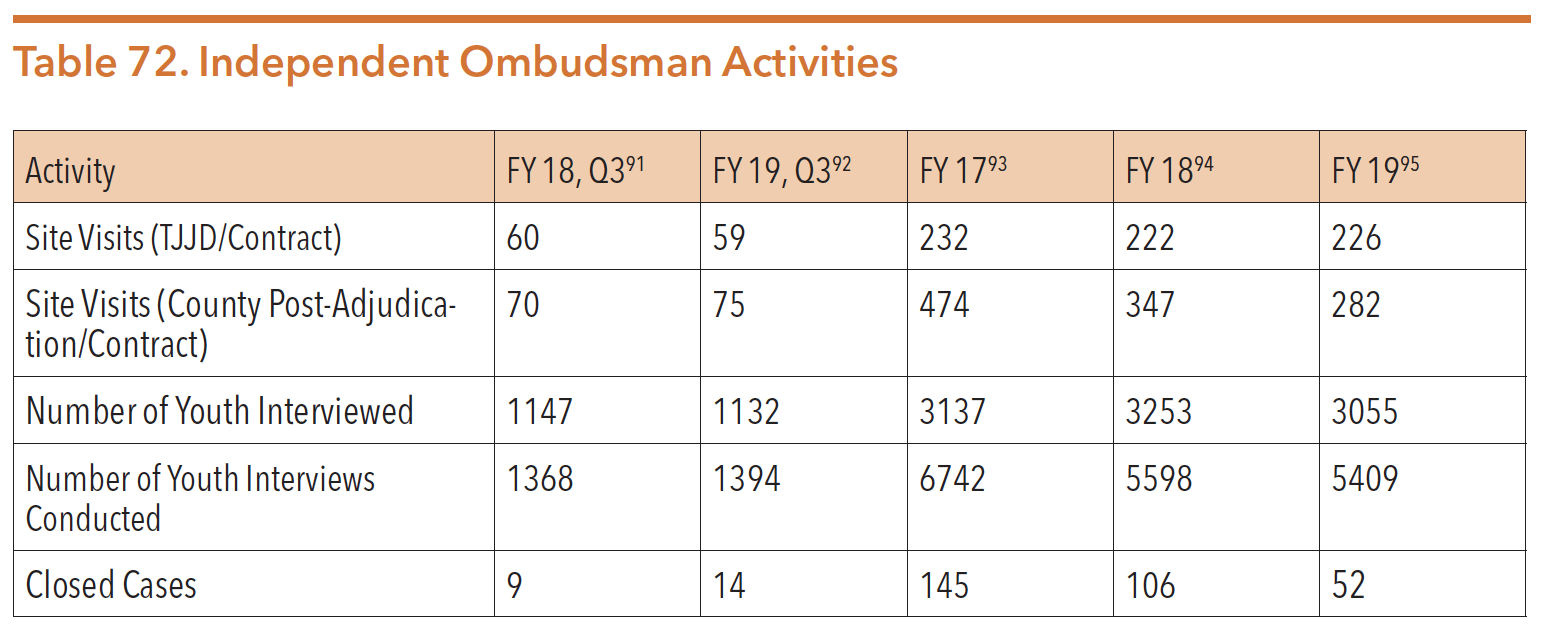

During the 84th legislative session, lawmakers expanded the IO’s oversight duties as part of a broader reform to the juvenile justice system. The IO’s responsibility for inspecting state-level secure TJJD facilities, halfway houses, state contract care facilities, and parole offices was expanded to include county-level post-adjudication facilities and contract facilities where county post-adjudicated youth are placed. The IO receives the majority of complaints directly from youth while inspectors visit state secure facilities and county post-adjudication facilities.90 The table below summarizes the IO’s activities during FY 2019 compared to earlier periods.

JUVENILE JUSTICE, MENTAL HEALTH, AND SUBSTANCE USE CONDITIONS

Other than serious violent behavior, youth are processed in a separate justice system rooted in different premises about adolescent behavior compared to the adult criminal justice system focused on adult behavior. In recent decades, significant advances in developmental and brain science have been cited as support for changes in juvenile justice policy. Research documents differences in adolescents’ decision-making capacity, risk taking, self-regulation, ability to delay gratification, and vulnerability to external pressure. While these studies are not probative in any specific case, the research is used in many localities to support emergent juvenile justice policies.

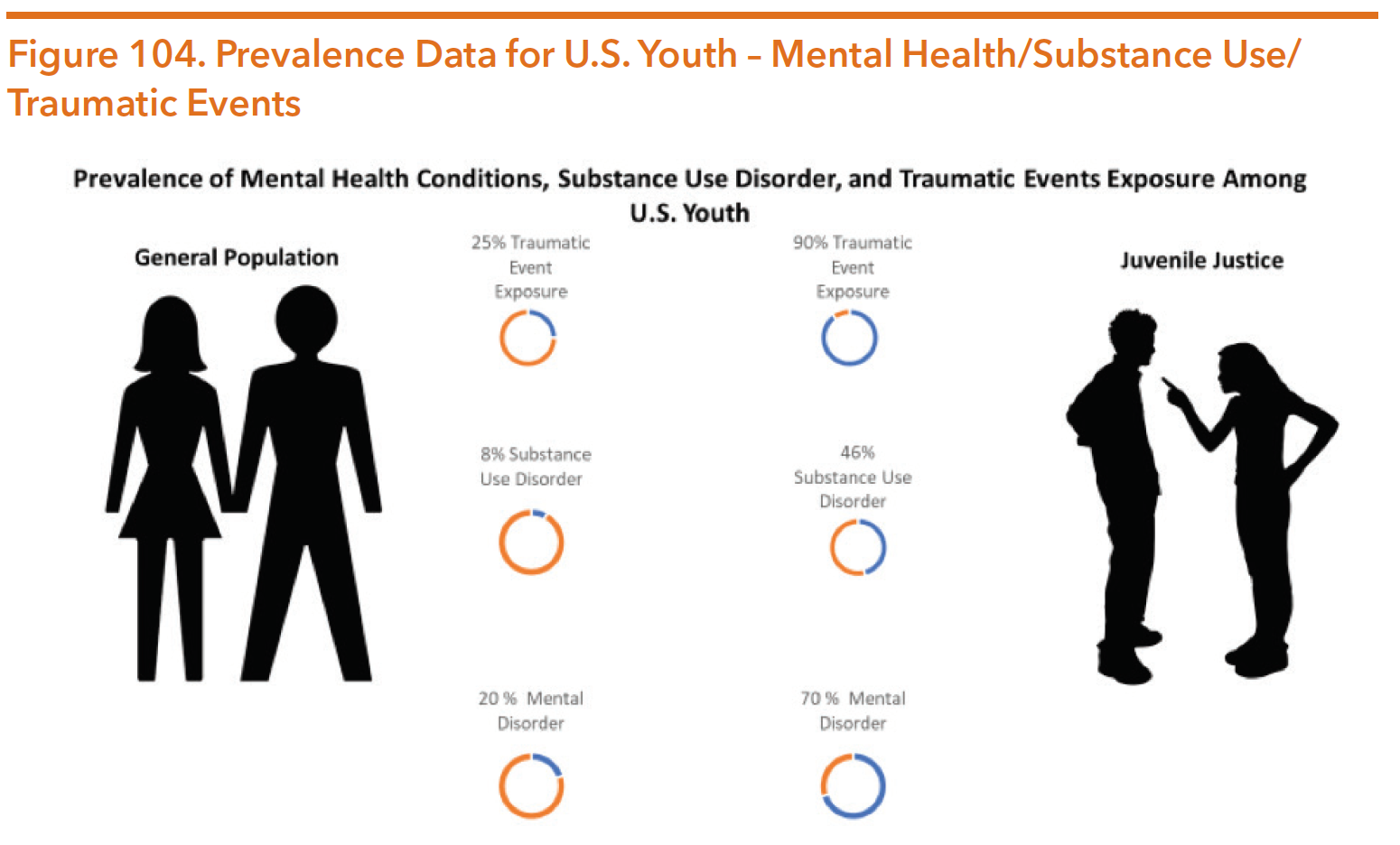

Youth in the juvenile justice system are more likely to have mental health and substance use conditions than youth in the general public. Researchers estimate that about 70 percent of justice-involved youth have a mental illness, while 60 percent of justice-involved youth have a co-occurring mental illness and substance usecondition. The figure below shows a side-by-side comparison of mental health needs for youth in the general population and youth in the juvenile justice population.

Source: National Center for Mental Health and Juvenile Justice & the Technical Assistance Collaborative. (2015). Strengthening Our Future: Key Elements to Developing a Trauma-Informed Juvenile Justice Diversion Program for Youth with Behavioral Health Conditions. Page 1. https://www.ncmhjj.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/traumadoc012216-reduced-003.pdf. Accessed 11 Apr. 2020.

According to the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP), a large proportion of youth in the juvenile justice system have a diagnosable mental health condition. Studies have suggested that about two-thirds of youth in detention or correctional settings have at least one diagnosable mental health problem With these rates of mental illness, OJJDP estimates that more than 670,000 youths in the juvenile justice system each year would meet diagnostic criteria for one or more conditions.

Approximately 70 percent of justice-involved youth around the country have a diagnosable mental health condition. In FY 2017, 99 percent of Texas youth committed to TJJD had a need for specialized mental health treatment, with 40 percent having at least a moderate level of need. The prevalence of substance use conditions is also high among youth in the juvenile justice system. A large multi-state study found a substance use diagnosis in 17 percent of youth at the point of intake, 39 percent at detention, and 47 percent at commitment to a secure facility post adjudication. In Texas, 78 percent of youth committed to TJJD in FY 2017 had a high or moderate need for substance use treatment.

Each year, millions of children are exposed to violence in their homes, schools, and communities. Left unaddressed, these traumatic experiences can lead to mental health and substance use conditions, school failure, increased risk-taking, and delinquent behaviors. Forty percent of justice-involved adults have been exposed to family violence by the time they reach adolescence. Some estimates show up to 75 percent of incarcerated men and women have experienced violence, abuse, or childhood neglect.

The Texas Penal Code (Section 22.04) defines a person with a disability (statutorily referred to as “disabled individual”) broadly as a person with mental illness, autism spectrum conditions, a developmental disability, an intellectual disability, severe emotional disturbance, traumatic brain injury, or a person “who otherwise by reason of age or physical or mental disease, defect, or injury is substantially unable to protect the person’s self from harm or to provide food, shelter, or medical care for the person’s self.” Thus, by statutory definition, any youth who has sustained brain injury trauma legally has a disability. Recent meta-analyses also demonstrate that between 30 percent and 60 percent of justice-involved youth have experienced a traumatic brain injury. After sustaining a brain injury, juveniles are more likely than their uninjured peers to engage in delinquent activity.

DISPROPORTIONALITY IN THE TEXAS JUVENILE JUSTICE SYSTEM

Black and Latinx youth tend to fare worse than their White peers throughout the juvenile justice process. For example, nationwide African American juveniles are more likely than White youth to be arrested, referred to juvenile court, sent to secure confinement facilities, and certified as adults.

The relationship between school disciplinary procedures and risk of juvenile justice contact, also known as the “school-to-prison pipeline” is the direct link to disproportionality in the juvenile justice system. In 2014, the U.S. Department of Education reported that, though youth of different races misbehave at similar rates, minority youth are more likely to be suspended and expelled from school. In Texas, researchers found that after controlling for 83 different variables, African American youth are 31 percent more likely than their White and Hispanic peers to receive a disciplinary action for a discretionary violation (e.g., a behavioral violation for which school administrators have the discretion to remove a student from the classroom environment, though they are not required to do so). Such disparities in school discipline place youth of color at greater risk for becoming involved in the juvenile justice system in the future.

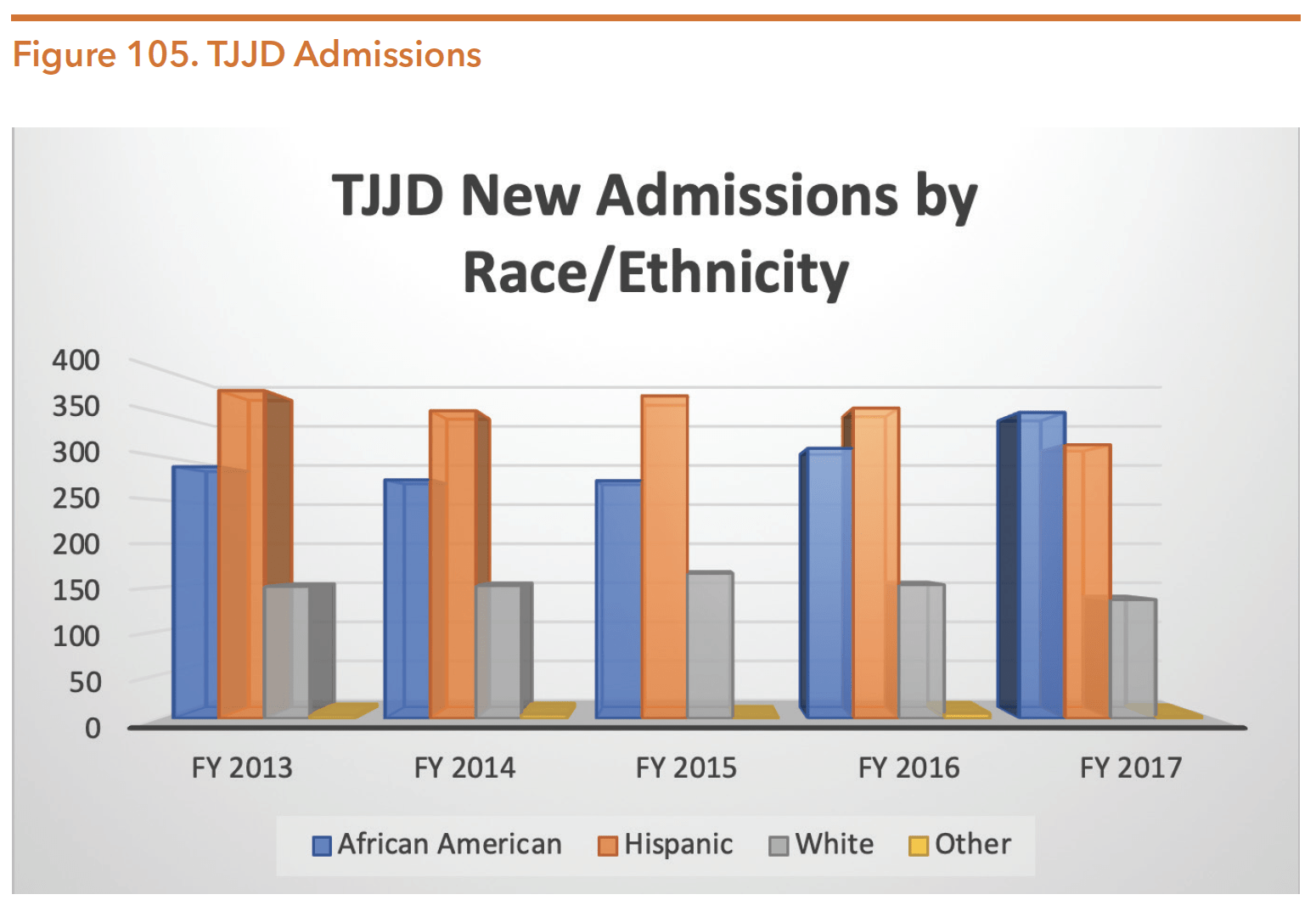

In 2015, researchers at the Council of State Governments Justice Center analyzed Texas juvenile justice reforms. Their study found that African American youth continue to make up a disproportionate share of commitments. The reforms did not appear to disproportionately exacerbate minority contact, alternatively they did not alleviate disparities. The figure below shows that from 2013 to 2017, the proportion of African American and Latinx youth newly admitted to TJJD was significantly higher than their White peers.

Source: Texas Juvenile Justice Department. Youth Characteristics. New Admissions FY 2013-FY 2017. https://www2.tjjd.texas.gov/statistics/youth-characteristics1317.pdf. Accessed 16 Apr. 2020.

The former Office of Minority Health Statistics and Engagement (OMHSE) was mandated to research, evaluate, develop, and recommend policies that address minority health (including in juvenile justice) to ensure equitable policies and practices in Texas. However, the OMHSE closed on September 1, 2018. Created in 2010 as the Center for Elimination of Disproportionality and Disparities, OMHSE was unique in its ability to look at systems data and identify where things weren’t working for certain populations. Currently, there is no office charged with specifically addressing disproportionality in the juvenile justice or any other Texas agency. Thus, disproportionality in Texas’s juvenile system continues despite overall youth population numbers declining.

Community-Based Behavioral Health Services for Justice-Involved Youth

TJJD, local juvenile probation departments, and Texas Correctional Office on Offenders with Medical or Mental Impairments (TCOOMMI) provide services for youth with mental health and substance use conditions in a variety of juvenile justice settings, including: state secure facilities, secure residential treatment centers, and county secure facilities. The agencies also provide services for youth who are under probation or parole supervision in the community.

A growing proportion of Texas justice-involved youth require and receive behavioral health services. In 2017, 99 percent of the newly-admitted youth to TJJD required at least one area of specialized mental health or substance use treatment and 87 percent had multiple areas of need. For youth admitted since FY 2009 and released by FY 2016, 61.5 percent of youth with high or moderate mental health needs successfully completed treatment. Over the last decade Texas closed eight state secure juvenile facilities; TJJD shifted from an agency focused on operating state juvenile correctional facilities to an agency devoting the majority of its budget to local juvenile probation departments for community supervision and services. Minimizing juveniles’ immersion in the justice system is the top priority in the TJJD 2017-21 strategic plan. Diverting youth with mental health conditions from incarceration and further involvement in the juvenile justice system has significant health and economic benefits. Youth who receive mental health and substance use services in the community can have the support of family and friends rather than being in an institution. Treatment is more affordable in the community compared to services within a juvenile justice facility. The FY 2019-23 strategic plan prioritizes spreading the Texas Model statewide, focusing on keeping youth as shallow as possible in the system and close to their communities, family members, friends, and support systems.

In 2015, TJJD began funding counties to ensure youth in the system stayed as close to home as possible. SB 1630 (84th, Whitmire/Turner), mandated TJJD funding to shift to regionalization. The legislation also created a task force that found medium- and low-risk youth had been committed to TJJD because of high needs for specialized treatment. The task force’s Regionalization Plan noted a need to prioritize diverting the following youth from TJJD commitment:

- Younger offenders (those between the ages of 10-12);

- Youth with a serious mental illness;

- Youth with a developmental or intellectual disability;

- Youth with non-violent offenses; and

- Youth with low- to moderate-risk levels for re-offense.

The plan anticipates youth’s specialized treatment needs and supports, encouraging counties to build out services to meet those needs. Further, the plan highlights that increasing services will ensure more youth with high- and moderately high-risk mental health and substance use needs can also be diverted from further system involvement.

NEED FOR BEHAVIORAL HEALTH SERVICES THROUGH JUVENILE PROBATION DEPARTMENTS

The recent juvenile justice state reforms focus on the concept that youth are different than adults, are still developing brain functionality, and are therefore less culpable. Youth are more impulsive, risk-taking, and less likely to consider the long-term consequences of their actions. However, youth are also more susceptible to rehabilitation than adult offenders due to their age-associated brain development.

TJJD’s Probation Services Division works with probation departments across the state to enhance the services offered to local youth referrals. The division works in all areas of juvenile justice by facilitating quality interaction between juvenile boards, juvenile probation departments, and other divisions within TJJD. As a liaison between TJJD and the field, the Probation Services Division is a resource for the continued success of the departments and TJJD.

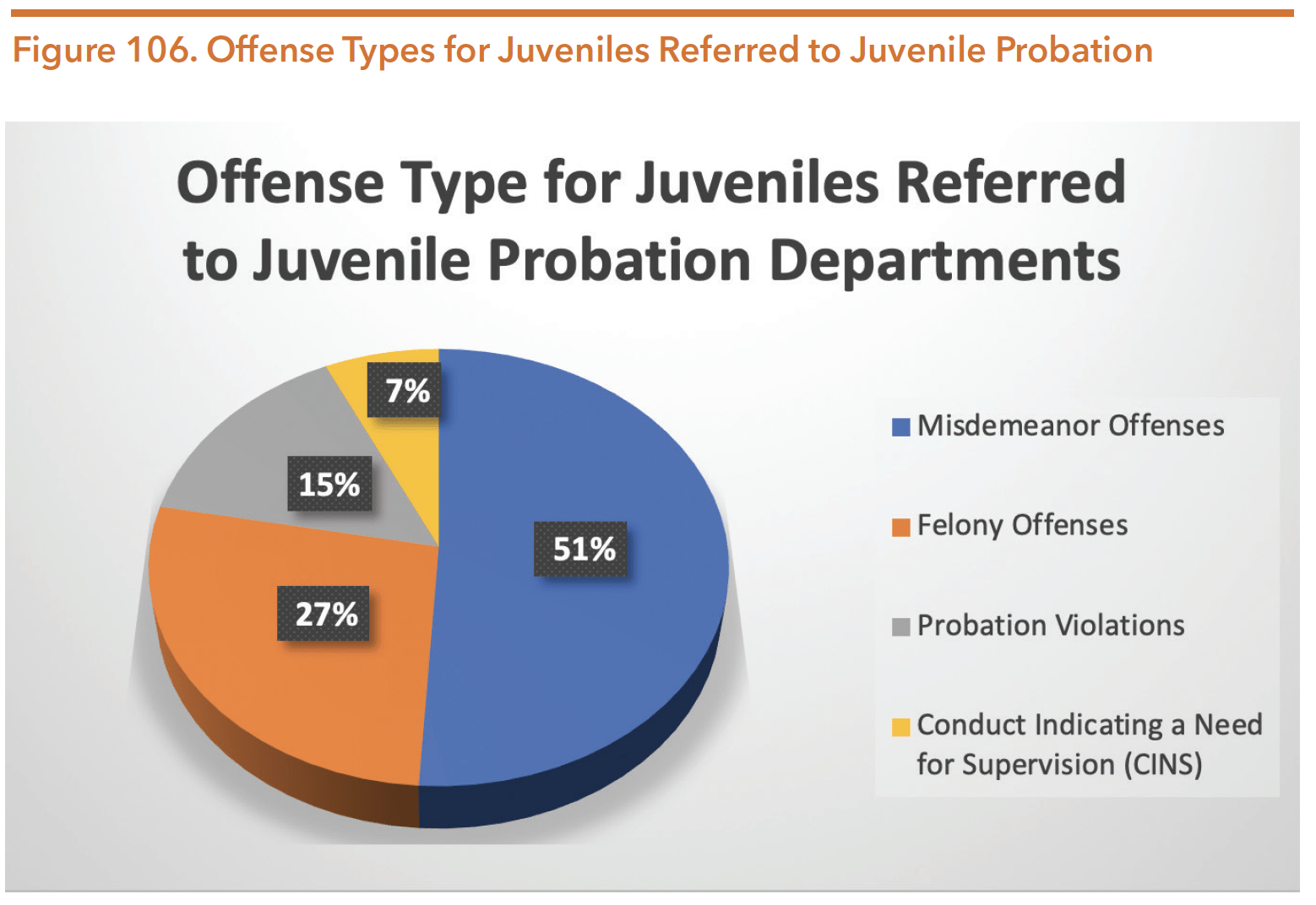

In FY 2018, juvenile probation departments received 53,228 formal referrals throughout the state, representing only a one percent drop from FY 2017. Just over a quarter (27 percent) of referrals were for felony offenses. The figure below shows the type of offenses that precipitated referrals to juvenile probation departments.

Texas Juvenile Justice Department. (December 2018). Annual Report to the Governor and Legislative Budget Board: Community Juvenile Justice Appropriations, Riders and Special Diversion Programs. Page 12. https://www2.tjjd.texas.gov/publications/other/rider-report-2018.pdf. Accessed 18 Apr. 2020.

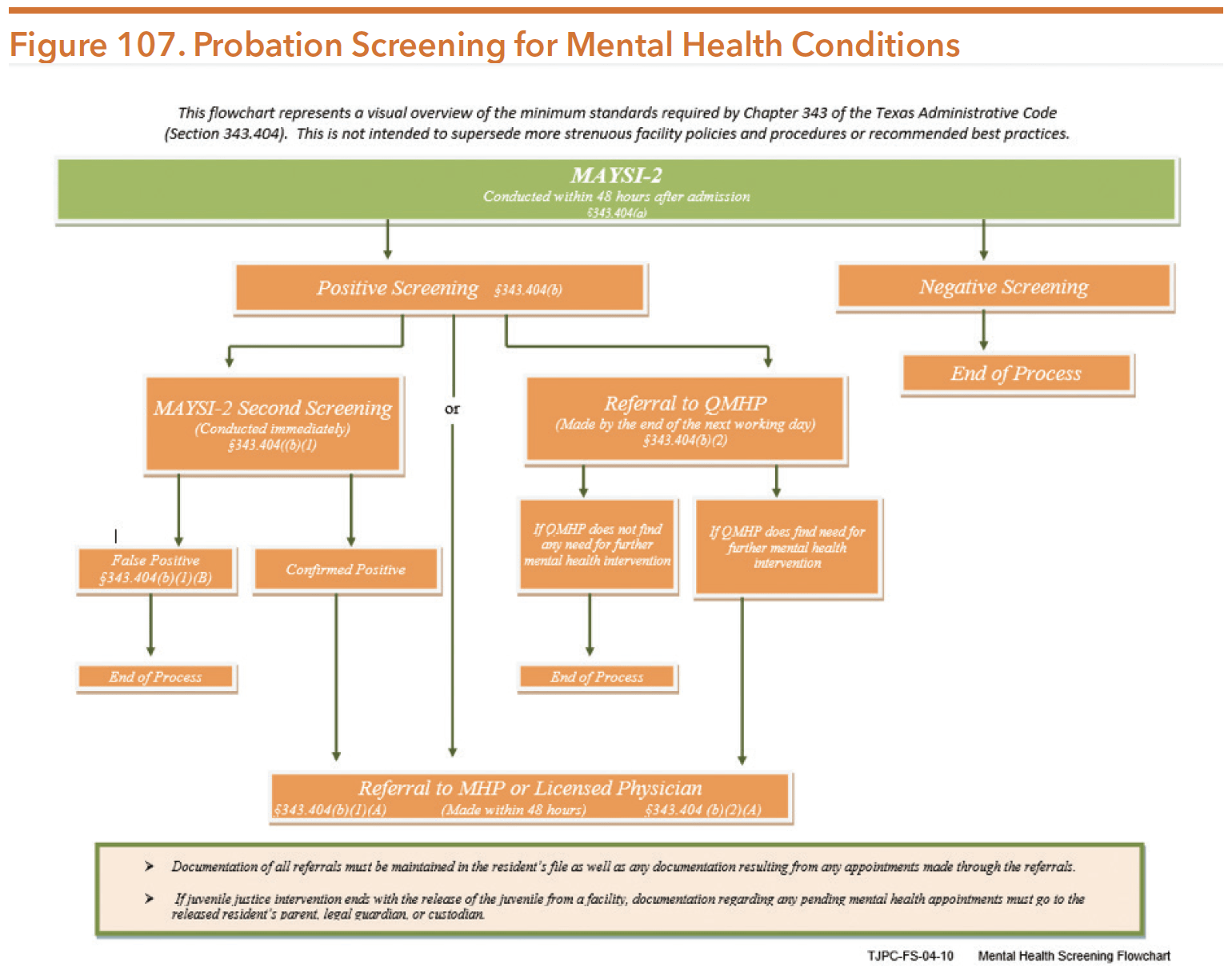

Required by state law, local juvenile probation departments must screen all youth for mental health needs within 48 hours of the juvenile’s admission to a pre- or post-adjudication facility using the Massachusetts Youth Screening Instrument (MAYSI-2). If a screening indicates that further assessment is appropriate, local juvenile probation departments must either: 1) conduct a second screening and refer the youth to a licensed physician within 48 hours, or 2) forgo a second screening and refer youth to a qualified mental health professional by the end of the next working day. The flowchart below demonstrates the steps taken to screen youth for mental health needs as they are referred to probation departments.

Source: Texas Juvenile Justice Department. (2010). Mental Health Screening Flowchart. http://www.tjjd.texas.gov/index.php/doc-library/category/161-monitoring-inspections. Accessed 18 Apr. 2020.

In FY 2018, 68 percent of youth under supervision by probation departments received at least one behavioral health service. Texas counties vary in their capacity to identify and address youth with mental health needs. Though there is a high prevalence of mental health needs among justice-involved youth, few juveniles access mental health services prior to entering the justice system. Unfortunately, many youth experience mental health treatment for the first time after they have been arrested, adjudicated, or diverted to mandated community treatment programs.

PARTNERSHIP WITH TEXAS CORRECTIONAL OFFICE FOR OFFENDERS WITH MEDICAL AND MENTAL IMPAIRMENTS (TCOOMMI)

County juvenile probation departments may partner with TCOOMMI, LMHAs, or Community Resource Coordination Groups (CRCGs) to provide justice-involved youth with behavioral health services. CRCGs are local interagency groups comprised of public and private entities that coordinate service delivery for juveniles across the state.

Youth with mental health and substance use needs may receive services for a variety of reasons. Some youth may be diverted from the probation system to receive mandated behavioral health services. Judges could also offer youth deferred adjudication and order treatment as a condition of dismissing each juvenile’s charges. Youth who are adjudicated and placed on probation may be required to participate in either residential or community-based programs, such as counseling or substance use treatment. Youth returning to the community after placement in a secure community or state facility may receive treatment as a condition of parole.

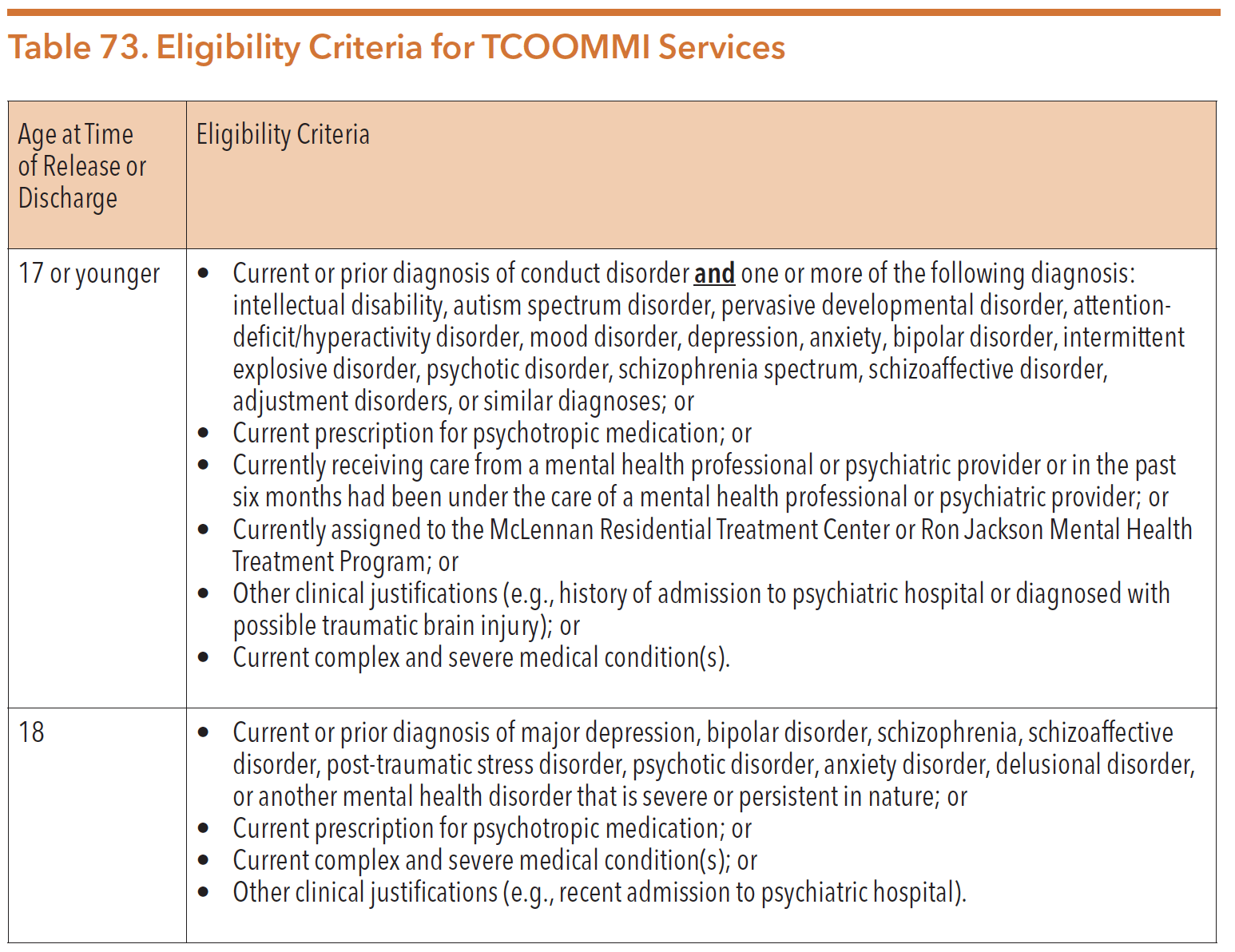

TCOOMMI coordinates continuity of care for some youth with a mental health diagnosis released on parole following their placement in a state or county secure facility. In March 2020, the average daily population on juvenile parole in Texas was 278 youth. Depending on fluctuating needs, the state may place paroled youth with a mental illness outside of their homes in community-based therapeutic foster homes, group living arrangements, or residential treatment facilities. Some youth receive intensive and collaborative wrap-around services that may include collaborative case planning, skills training and education, psychiatric services and medication monitoring, individual and/or group therapy, early intervention, vocational services, benefits eligibility services, and parental support and education. TCOOMMI also participates in the Texas System of Care and the statewide Community Resource Coordination Group Committee to address systems issues. The table below outlines TCOOMMI eligibility criteria.

Source: Texas Juvenile Justice Department. (2018, September 21).

COMMUNITY-BASED PROGRAMS AND SERVICES

In 2010, TJJD created its online Program and Services Registry to manage information about community-based programs. The registry catalogues all active community-based programs offered by various juvenile probation departments statewide. Both juvenile probation departments and contracted agencies provide information regarding the service components of active programs, including their duration, funding, and eligibility requirements.

In FY 2018, local juvenile probation departments offered 1,448 community-based programs to at-risk youth, justice-involved youth, and their families. These programs involved a wide array of services including counseling services, gang intervention programs, parenting classes, and employment training. In FY 2018, 34 percent of youth participants were enrolled in a treatment-based program, 39 percent were enrolled in a skill-building/activity-based program, and 27 percent were enrolled in a surveillance-based program.

Juvenile probation departments do not always wait until disposition to enroll a juvenile in needed programming. Across the state, 713 programs allow juveniles who are awaiting disposition to participate in programs. Of the juveniles enrolled in a predisposition program, 6,210 (55 percent) were under temporary pre-court monitoring or conditional pre-disposition supervision in FY 2018.

Of the juveniles served in a community-based program during FY 2018, a majority (76 percent) were under deferred prosecution or probation supervision. Half of the juveniles under deferred prosecution or probation supervision and enrolled in programming were referred for class A or B misdemeanor offenses (50 percent), while 45 percent were referred for felony offenses.

Community-based programs are not dispersed evenly across the state’s 168 juvenile probation departments. The availability of community-based programs depends upon local county resources and the unique needs of youth in a particular community. Historically, smaller probation departments offer an average of five programs per department. However, smaller departments often lack targeted programs such as mental health courts or runaway programs that are typically available in larger counties. Smaller departments provide counseling and educational programs designed to serve the needs of a wide array of juveniles, not only those with more specific behavioral health needs.

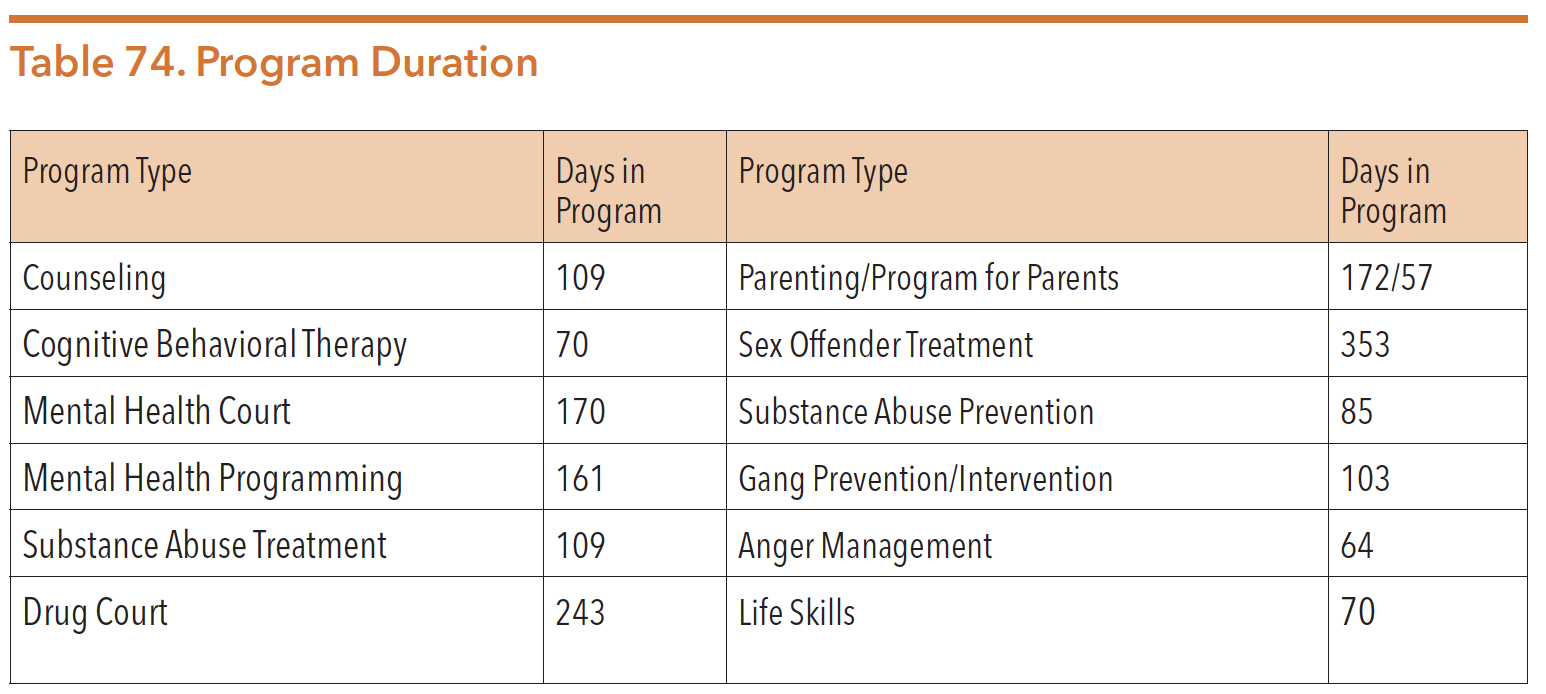

The duration of community-based programs also varies widely between counties. Some programs last one afternoon while others can last the entirety of a juvenile’s supervision period. The table below lists the average duration of service for community-based programs. Programs with behavioral health components as determined by a 2013 evaluation are listed on the left, all other programs on the right.

Source: Texas Juvenile Justice Department. (2013). Community-Based Program Evaluation Series: Overview of Community-Based Juvenile Probation Programs. Page 5. https://www2.tjjd.texas.gov/statistics/CommunitybasedJuvenileProbationPrograms.pdf

SPECIAL PROGRAMS AVAILABLE TO LOCAL JUVENILE PROBATION DEPARTMENTS

TJJD partially funds programs in local juvenile probation departments through diverse initiatives and grants. The programs aim to keep youth out of state-operated secure facilities and instead serve them in their local communities. The following section describes a variety of programs with behavioral health components that are available to local juvenile probation departments.

THE FRONT-END DIVERSION INITIATIVE

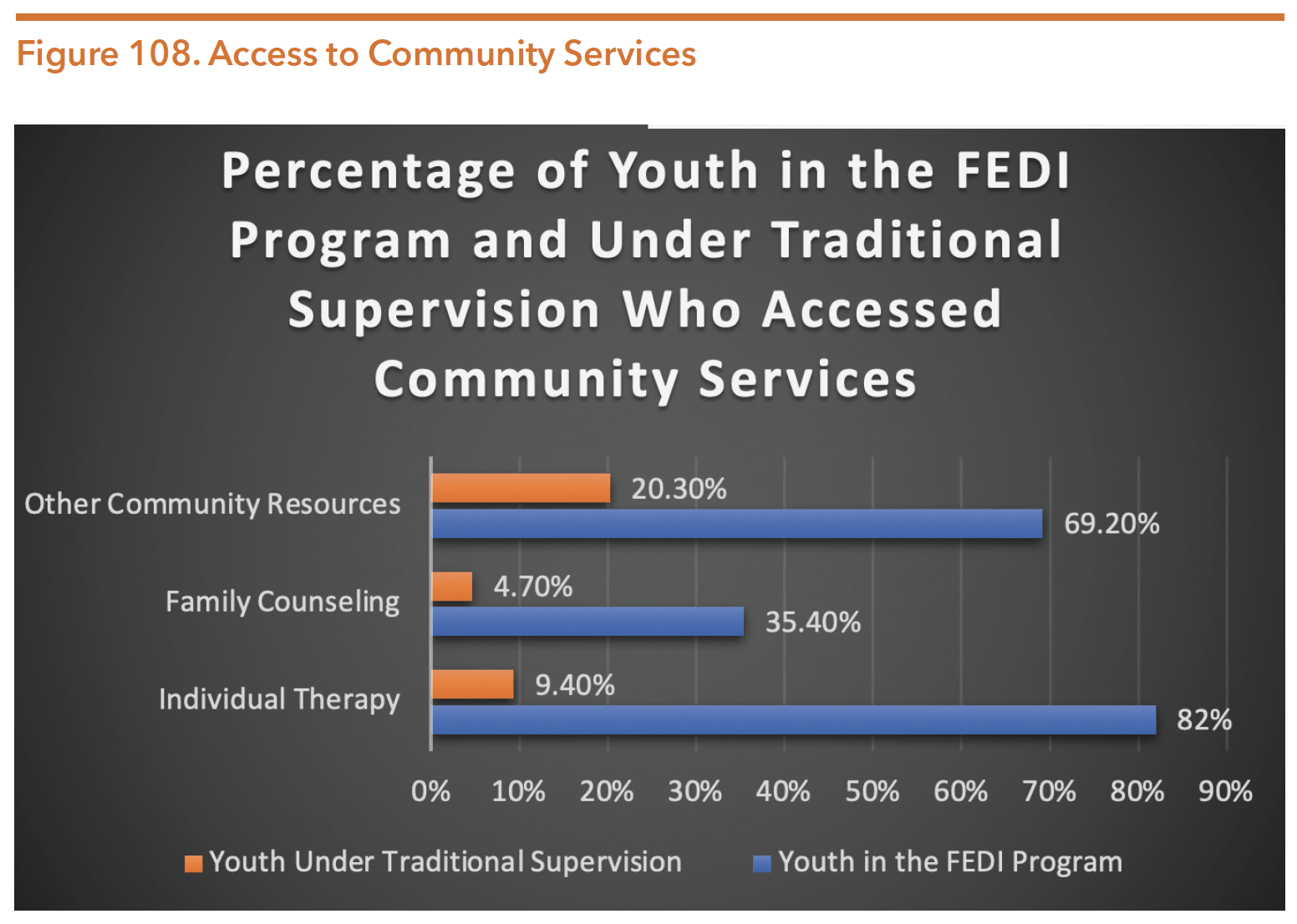

In 2008, TJJD used MacArthur Foundation funding to develop the Front-End Diversion Initiative (FEDI) in partnership with local probation departments to divert youth away from the justice system before they are formally adjudicated. FEDI links youth with mental health needs to specialized juvenile probation officers (SJPOs) with comprehensive training on mental illness, family engagement, de-escalation, and problem-solving techniques. For approximately three to six months, SJPOs meet with enrolled juveniles and their families on a weekly basis to fulfill each youth’s crisis stabilization plan and connect juveniles to community resources. After the supervision period, juveniles, their families, and their SJPOs create an aftercare plan that outlines ongoing support systems that youth may use once they formally exit FEDI.

Five Texas counties implemented FEDI programs: Bexar, Dallas, Lubbock, Travis, and Harris. In 2014, the National Institute of Justice designated FEDI as a “Promising Program” for its successes with pre-adjudicated youth. Some of FEDI’s successes include:

- Within 90 days of supervision, FEDI participants were 11 times less likely to be adjudicated than their peers who received traditional supervision services.

- Four FEDI sites (Austin, Dallas, Lubbock, and San Antonio) reported a 0 percent turnover rate among SJPOs, while most juvenile probation departments reported a 35 percent turnover rate over four years.

- FEDI officers engaged in over 10 times more collateral contacts in the community than traditional probation officers did, leading participants to use more community services than other justice-involved youth.

The figure below illustrates the difference in the use of community services among youth enrolled in the FEDI program and youth receiving traditional supervision services.

Source: National Center for Mental Health and Juvenile Justice. (2015). Diverting Youth at Probation Intake: The Front-End Diversion Initiative. Page 5-6. https://www.ncmhjj.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/FEDI-ARIAL-508-final.pdf. Accessed 20 Apr. 2020.

THE SPECIAL NEEDS DIVERSIONARY PROGRAM

Through the Special Needs Diversionary Program (SNDP), TJJD and TCOOMMI seek to rehabilitate and prevent future justice involvement among post-adjudication youth with diagnosed mental health conditions (excluding substance use conditions, intellectual disabilities, autism, and pervasive development conditions). Specialized probation officers partner with mental health professionals from LMHAs to provide diverse services, including mental health services such as individual and family therapy; probation services such as life skills training, anger management, and mentoring; and parental support and education services. The program requires in-home contact with the youth and family, small caseloads, and 24/7 access for crisis resolution services.

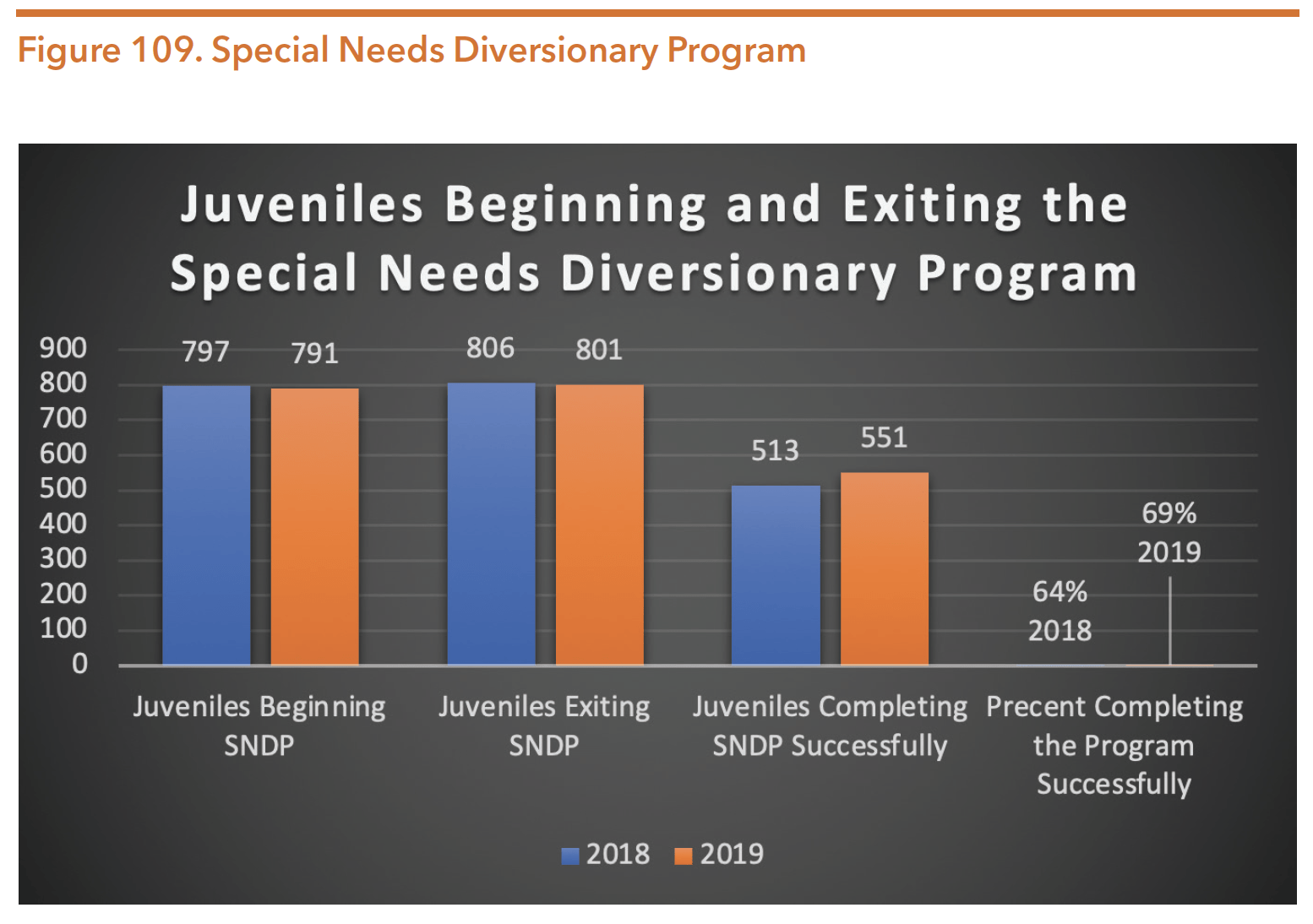

In FY 2019, the Texas Legislature appropriated $1,895,175 to SNDP, serving 1,208 juveniles with a diagnosed mental health need other than substance abuse, intellectual disability, or autism spectrum conditions in 19 local juvenile probation departments. During the fiscal year, 791 juveniles began the program in the year, while 801 juveniles completed the program.

The figure below shows program details for youth in SNDP FY 2018-2019.

Source: Texas Juvenile Justice Department. (2017). Special Needs Diversionary Program (SNDP) 2018-2019 Summary Requirements. Page 18. https://www2.tjjd.texas.gov/publications/standards/GrantsM/18-19_SummaryRequirements.pdf. Accessed 20 Apr. 2020.

PREVENTION AND EARLY INTERVENTION PROGRAMS

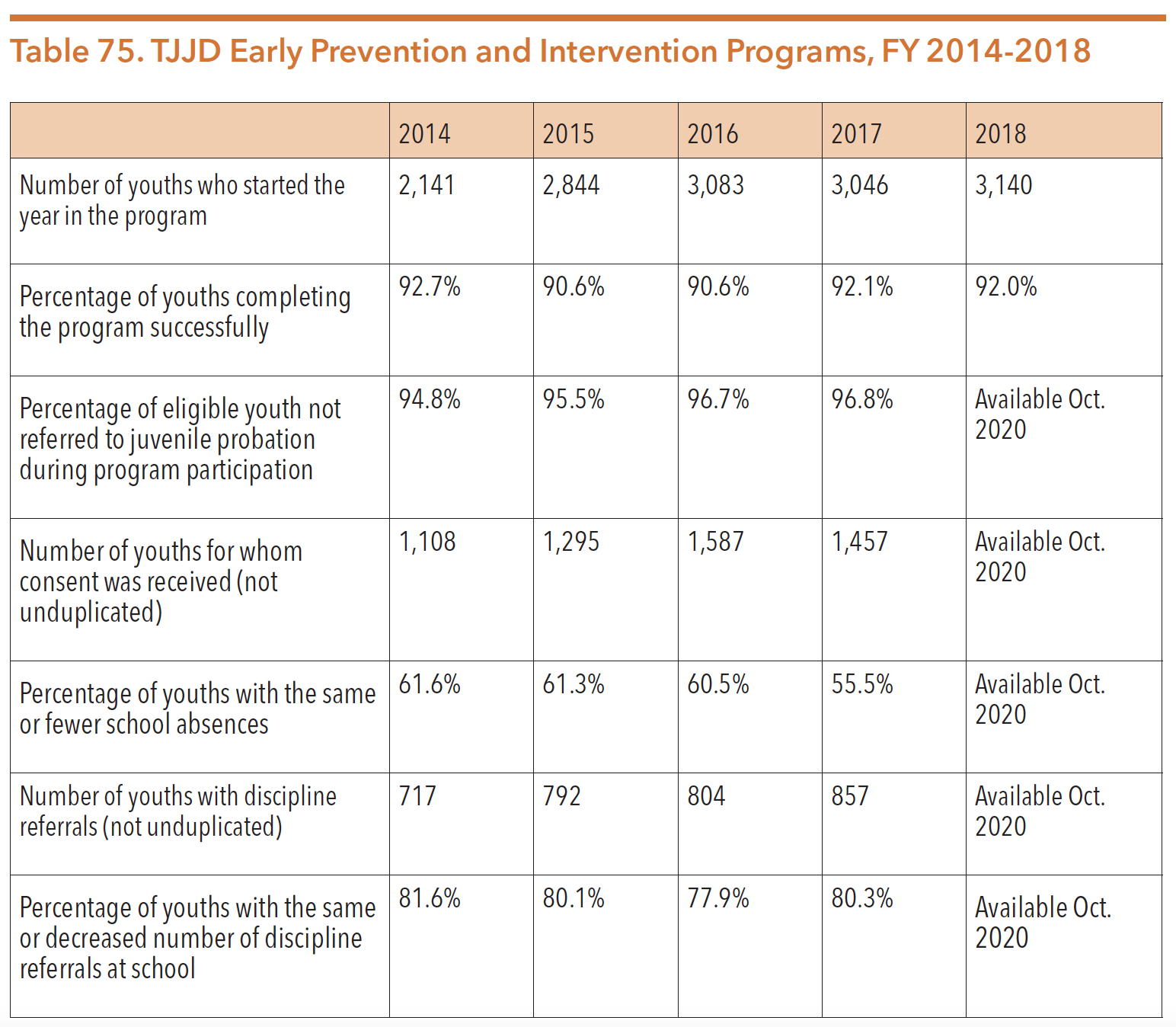

In 2011, the 82nd Texas Legislature funded prevention and intervention services to stop “at-risk behaviors that can lead to delinquency, truancy, school dropout, or referral to the juvenile justice system.” Legislation required the services focus on youth ages 6 to 17 who are not currently receiving supervision services who are at high risk for referral to the justice system. In FY 2017, over $3.1 million was appropriated for prevention and early intervention services, and 35 counties were awarded funding. The juvenile probation departments focused on providing youth with educational assistance, skills building, character development, mentoring services after school and during the summer, and skills, services, and supports to parents and guardians of at-risk youth.

In FY 2018, 35 counties received 37 grant awards totaling $3,012,177 for early prevention and intervention programs.159 During that fiscal year, 3,852 youth participated in TJJD-funded prevention and intervention programs. The average age of youth referred to a grant-funded prevention and intervention program was 11 years old, significantly younger than the average age of 15 years old for juveniles formally referred to juvenile probation departments in the fiscal year. Of those served in a grant-funded prevention and intervention program, 42 percent were Latinx and 14 percent were African American. Just over half (54 percent) of the youth served were male. Forty-six percent of the youth served in a prevention and intervention program were female, compared to youth formally referred to juvenile probation departments in the fiscal year, which were 28 percent female.

The 84th legislature required TJJD to partner with DFPS, TEA, and the Texas Military Department in the provision of juvenile delinquency prevention and intervention programs. The workgroup shared key considerations:

- Truancy reform to shift dropout and delinquency prevention and provide needed intervention services.

- Active, untreated behavioral health concerns in students who drop out.

- School Districts of Innovation to provide opportunities for dropout and delinquency prevention and intervention efforts.

The table below shows available data outcomes for the past five years.

Source: Texas Juvenile Justice Department, Texas Department of Family and Protective Services, Texas Education Agency &Texas Military Department. (October 2019). Agency Coordination for Youth Prevention & Intervention Services. Page 8. http://www.tjjd.texas.gov/index.php/doc-library/send/466-reports-on-coordination-for-prevention-intervention/2215-report-coordination-prevention-intervention-2019. Accessed 11 May 2020.

COMMITMENT DIVERSION PROGRAM (GRANT C)

In 2009, the 81st Legislature created the Commitment Diversion Program (Grant C). The state provides funds through the program to local juvenile probation departments to develop community-based rehabilitative services and divert youth away from TJJD facilities. The funds support a range of supportive services such as counseling, educational programs, life skills courses, and electronic monitoring – all of which are designed to keep youth out of state-operated facilities while maintaining public safety.

In FY 2018, 4,955 juveniles received a program, placement, or service funded at least in part by Community Diversion (Grant C) funds. Ninety-five percent of juveniles received one type of service through the grant, while 5 percent received a combination of two or more types of services. Although juveniles on deferred prosecution supervision are eligible for Commitment Diversion services, juveniles served in the year were primarily on probation supervision (72 percent ).

REGIONAL DIVERSION ALTERNATIVES PROGRAM (GRANT R)

The 84th legislature required TJJD to develop a plan focused on reducing commitments to state secure facilities by diverting youth of low to moderate risk of re-offending. Youth with a serious mental illness were highlighted as a focused population for diversion. Regional Diversion Alternative Program grants serve to reimburse juvenile probation departments on a case-by-case basis for services to divert eligible youth from TJJD secure placements. Departments can also apply for Grant R funds to increase availability of evidence-based, intensive community-based, residential, reentry, and aftercare programs that improve the department’s capacity to treat youth locally.

MULTI-SYSTEMIC THERAPY (MST) FOR JUVENILE OFFENDERS

Multi-Systemic Therapy (MST) for juvenile offenders addresses the multidimensional nature of behavior problems in youth. Treatment focuses on those factors in each youth’s social network that are contributing to their antisocial behavior. MST is delivered in the natural environment, like the youth’s home, school, or other location in their community. The typical duration of home-based MST services is approximately 4 months, with multiple weekly therapist-family contacts. MST addresses risk factors in an individualized, comprehensive, and integrated fashion, allowing families to enhance protective factors. Specific treatment techniques are based on empirically supported therapies, including behavioral, cognitive behavioral, and pragmatic family therapies.

The ultimate goal of MST is to empower families to build a healthier environment through the mobilization of existing child, family, and community resources. MST has documented positive outcomes for youth and their families who participate in the therapy. Compared to youth receiving usual-treatment services, those receiving MST were arrested about half as often in the post-treatment period. Recidivism rates were significantly less for MST-treated youth. Youth who received MST also had an average of 73 fewer days of incarceration.

Post-treatment reports of alcohol and marijuana use, and other drug use are typically less frequent among MST participants than those receiving usual-treatment services. Further, post-treatment assessments also show that family cohesion increased among families receiving MST therapy. Finally, reports of aggression with peers show a significant decrease for MST participants compared to those receiving usual-treatment services. The Judicial Commission on Mental Heath’s legislative research committee recommended MST for more study and application for the upcoming 87th legislative session.

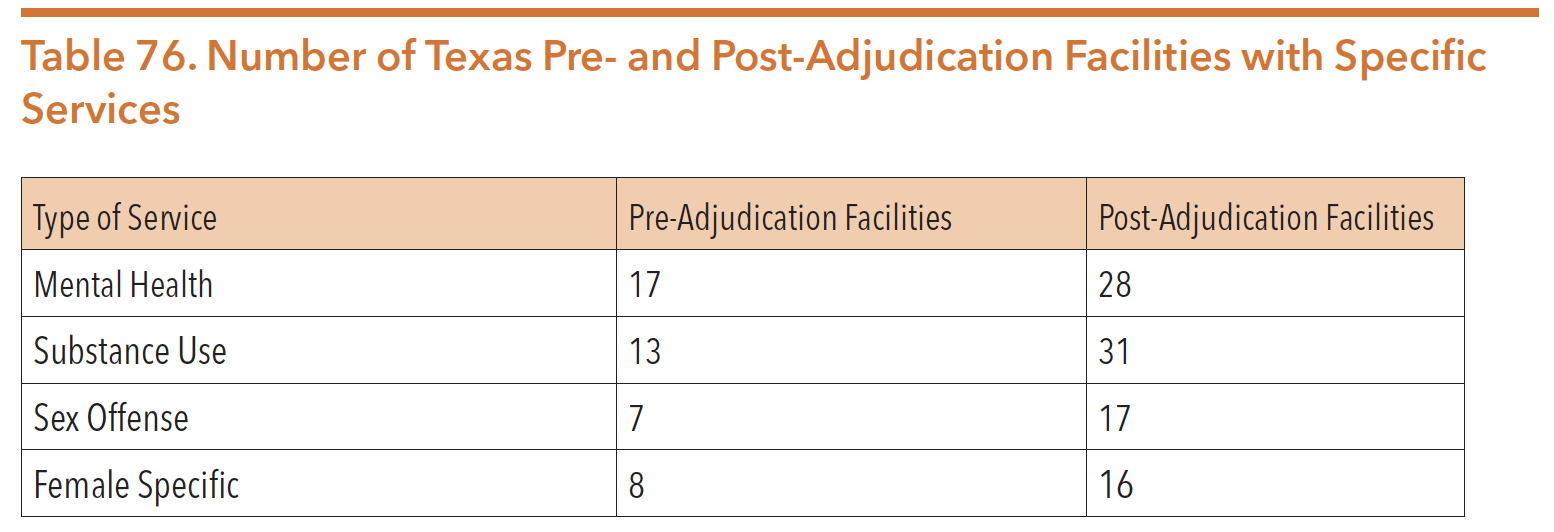

Behavioral Health Services in County- Level Secure Facilities

At the county level, juveniles may be placed in two types of secure facilities that offer behavioral health services: pre-adjudication detention and post-adjudication correctional facilities. As of April 2020, select Texas counties operated 45 secure juvenile pre-adjudication detention facilities for the purpose of detaining juveniles who are deemed unsafe or inappropriate for release back into the community while awaiting their adjudication and/or disposition hearings. These juveniles can be detained until a juvenile judge provides a “true” or “not true” finding for each youth’s offense.

Texas also has 35 post-adjudication secure facilities operated at the county level. These facilities detain adjudicated youth who have committed offenses that are not severe enough to warrant placement in a state secure facility. They also may detain adjudicated youth who are waiting for placement in a treatment program for substance use or mental health challenges.

Because local juvenile justice systems rely heavily on county and local funding sources, the availability of treatment and support services varies across the state. The table below displays the number of pre- and post-adjudication facilities that offer specialized mental health, substance use, sex offense, and female-specific services. For a full listing of all county-level juvenile justice facilities and the services offered by each, visit: https://www2.tjjd.texas.gov/publications/other/searchfacilityregistry.aspx.

Source: Texas Juvenile Justice Department. (n.d.). Registered Juvenile Facilities in Texas (CY2020). https://www2.tjjd.texas.gov/publications/other/searchfacilityregistry.aspx. Accessed 20 Apr. 2020.

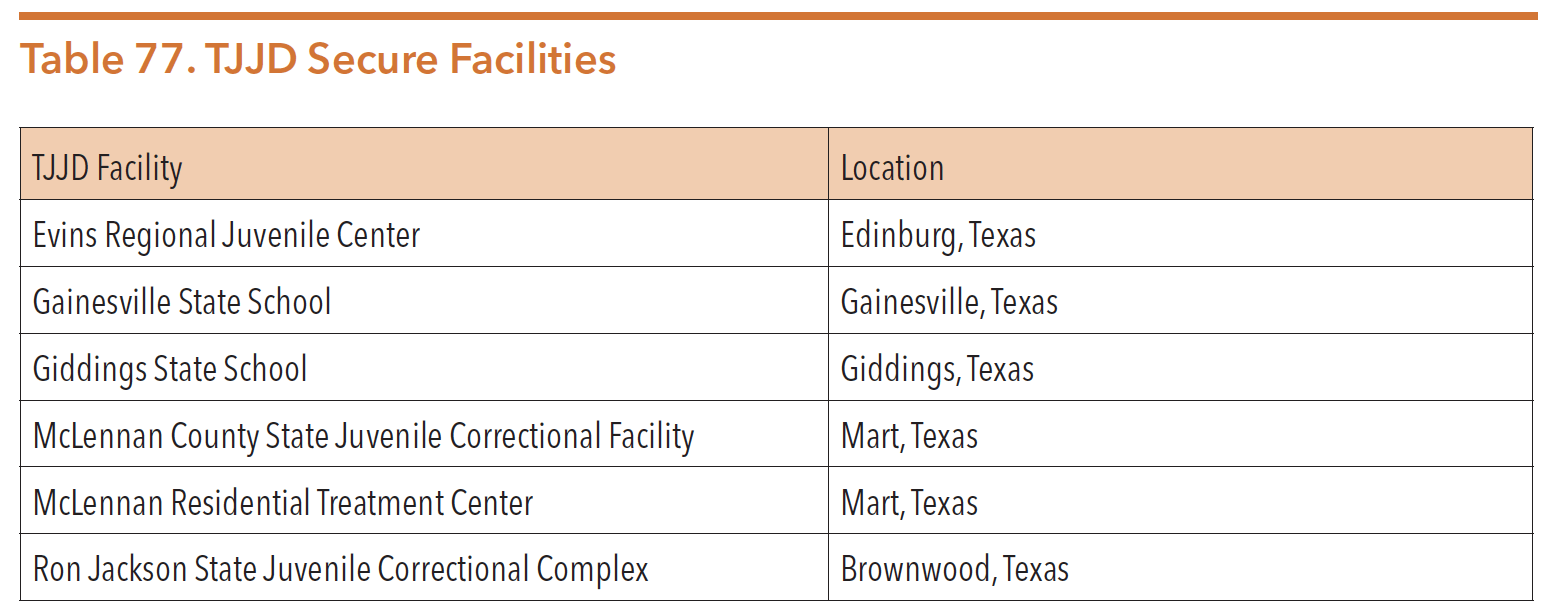

Behavioral Health Services in State Secure Facilities

Texas operates six state secure facilities for youth adjudicated for felony offenses.183 On April 20, 2020, there were 1,033 youth housed at the state’s six secure facilities. The table below details the state secure facilities. In FY 2018, 25 percent of newly-committed youth were adjudicated for high-severity crimes, such as capital offenses.

Source: Texas Juvenile Justice Department. (n.d.). TJJD Facilities Address List. https://www2.tjjd.texas.gov/aboutus/facilities.aspx. Accessed 20 Apr. 2020.

INTAKE, ORIENTATION, AND PLACEMENT

A TJJD secure facility is the most serious place a juvenile offender can go within the juvenile system. Once in a secure facility, youth are in the care and custody of the state and are assigned to either high, medium, or low security facilities. The high security facilities are surrounded by fences with controlled, secure entrances monitored by law enforcement officers. The medium or low security facilities are not fenced.

The first step for a youth in TJJD is an orientation and assessment unit. For girls, it is at the Ron Jackson State Juvenile Correctional Complex in Brownwood, Texas. Boys go to the McLennan County State Juvenile Correctional Facility in Mart, Texas. Prior to placement in a secure facility, each youth receives orientation and assessment services. During orientation and assessment, staff determines the strengths and needs of each youth. Medical, emotional, educational, and psychological needs are evaluated. The result for each youth is an individualized treatment plan that is evaluated and retooled as necessary while youth move through TJJD.

After orientation, youth are relocated to various state secure facilities depending upon the juvenile’s specific treatment needs. Approximately 15 percent of youth are placed in a halfway house following orientation, while many other juveniles in state custody fulfill their dispositions within secure detention facilities.

Prior to November 2013, the Ron Jackson State Juvenile Correctional Complex only served females. However, the facility transitioned from an all-girls complex to a co-ed complex in order to make more efficient use of the facility’s existing bed space. Programming and services at Ron Jackson are designed to be similar to those offered at the McLennan County Residential Treatment Center but are modified to reflect the unique needs of female youth.

In October 2014, the Ron Jackson complex created a male intake unit for boys under 15 years old. Children under 15 who have been committed to a state secure facility remain at the Ron Jackson facility until they are about 14 years old. At that time, TJJD and juvenile court stakeholders may choose between three courses of action depending upon the individual child’s treatment needs:

1. The child may remain at Ron Jackson to finish his or her assigned sentence;

2. The child may be sent to another secure facility that can meet his or her treatment needs; or

3. The child may be transferred to a halfway house or to the community if TJJD staff members determine that release is both safe and clinically appropriate.

REHABILITATION AND SPECIALIZED TREATMENT PROGRAMS

All six state secure facilities use a multi-faceted rehabilitation program called CoNEXTions, which provides life skills training, education, and workforce development services to all committed youth. Juvenile justice programs traditionally focus on establishing control over youth. The CoNEXTions program instead uses an evidence-based therapeutic framework that incentivizes positive behavioral change and connects youth with social support systems. The program aims to reduce criminogenic risk factors, increase protective factors, and decrease recidivism among justice-involved youth.

Psychiatric and psychological services are also available within all secure facilities. Male youth with severe mental health needs are taken to TJJD’s primary mental health treatment facility, the McLennan Residential Treatment Center (MRTC) in Mart, Texas. Females with severe mental health needs stay at the Ron Jackson facility in Brownwood, Texas. Youth, both male and female, with the most mental health needs and who also pose a danger to themselves or others are be served within MRTC’s Crisis Stabilization Unit (CSU). Equipped with eight beds, the CSU provides crisis intervention psychiatric care. Juveniles may be admitted to the CSU only if their psychiatric crisis presents a risk of serious harm to themselves or others, the crisis could lead to deterioration if left untreated, and placement in the CSU is the least restrictive intervention that is available to and appropriate for the youth.

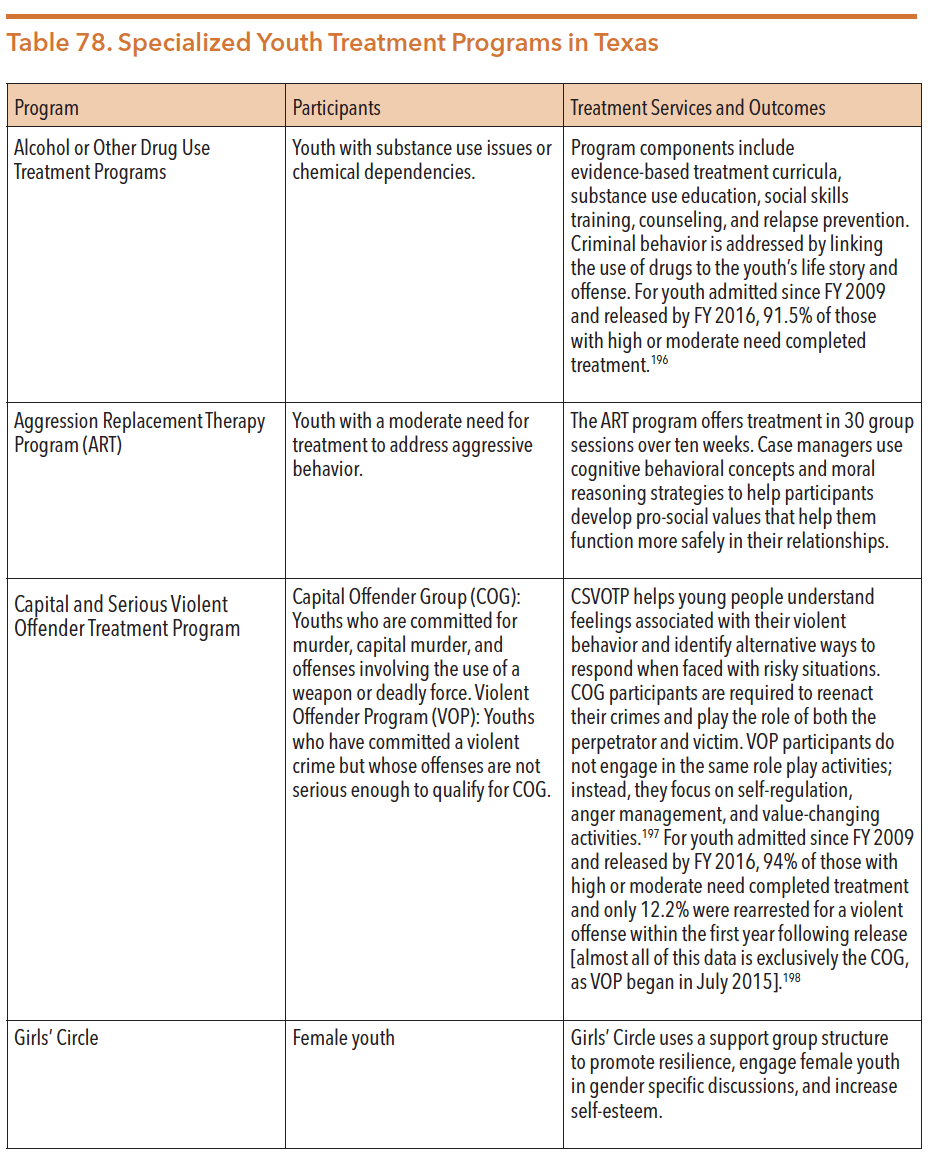

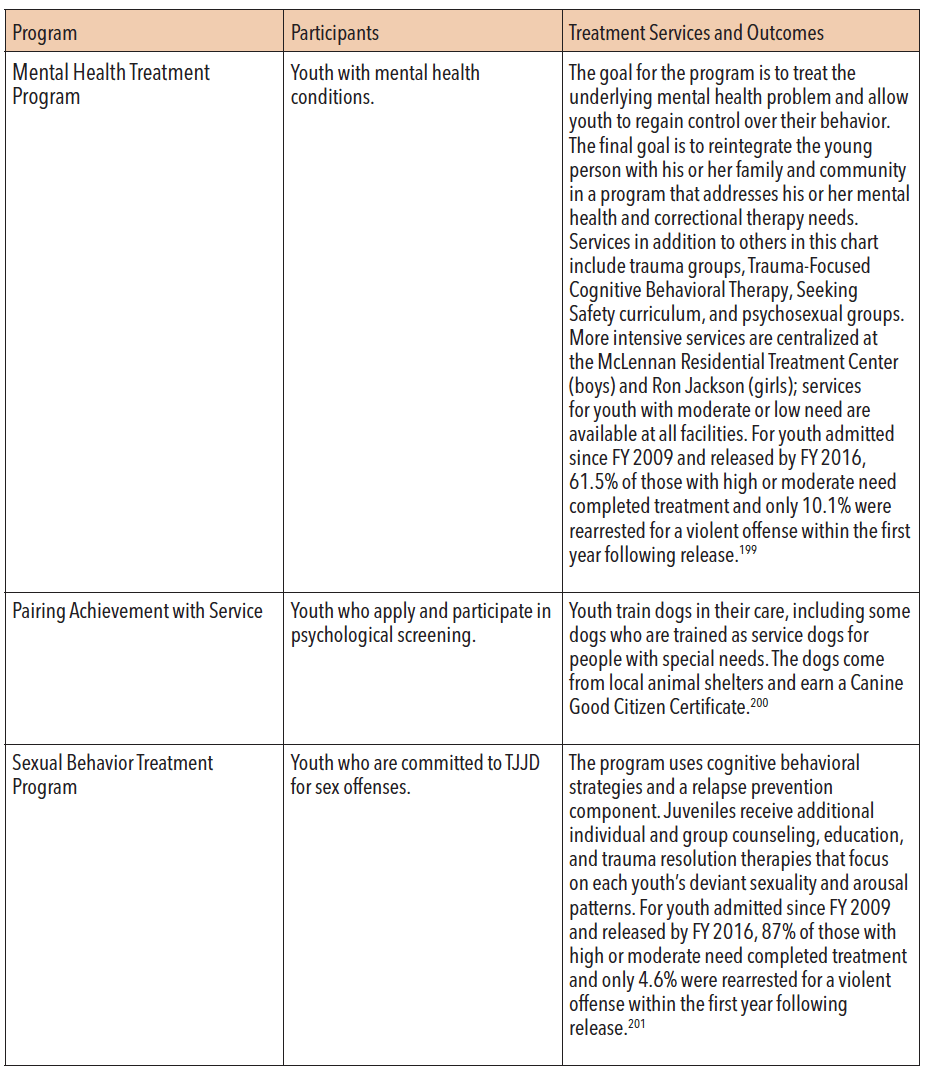

Youth who are identified as having a high need for specialized mental health and substance use services or who are at high risk for violent recidivism are assigned to specialized treatment programs within TJJD. These specialized treatment programs are designed for youth who have committed serious violent or sexual offenses and/ or youth with substance use conditions, mental health conditions, or intellectual disabilities. The table below highlights the specialized treatment programs that exist at the six state secure facilities.

Source: Texas Juvenile Justice Department. (December 2017). The Annual Review of Treatment Effectiveness. http://www.tjjd.texas.gov/index.php/component/jdownloads/send/593-annual-treatment-effectiveness-review-archive/1198-annual-treatment-effectiveness-review-2017?option=com_jdownloads. Accessed 21 Apr. 2020.