*Note: If you find the text on some of the images blurry or hard to read, right-clicking the image and then selecting “open image in new tab” may improve the issue.

Policy Concerns

- Providing low-income Texans with mental health and/or substance use conditions who are ineligible for Medicaid access to supports and services.

- Expanding Medicaid to ensure individuals with mental health and/or substance use conditions have access to treatment, services, and supports.

- Ensuring adequacy of Medicaid reimbursement rates for mental health, substance use, and primary care services and providers.

- Planning for the discontinuation of Medicaid 1115 Transformation Waiver funding and the sustainability of Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) projects providing behavioral health services.

- Continuing efforts to enforce mental health and substance use parity within Medicaid and CHIP.

- Addressing Texas having the highest uninsured rate of both adults and children in the country.

- Monitoring and ensuring mental health, substance use, and primary care network adequacy in Medicaid managed care.

- Ensuring access to quality community-based mental health and substance use services through integrated service delivery and managed care models that emphasize recovery, prevention, and continuity of care.

- Protecting state funding for substance use services to keep Texas from being penalized for the required Maintenance of Effort (MOE) requirement for federal block grant funding.

- Addressing mental health and substance use workforce shortage issues, particularly the lack of diverse providers and availability in rural areas.

- Expanding opportunities for peer support specialist, recovery coach, and family partner support services.

- Addressing the Medicaid reimbursement rates for peer services to reflect their importance and incentivize utilization by providers.

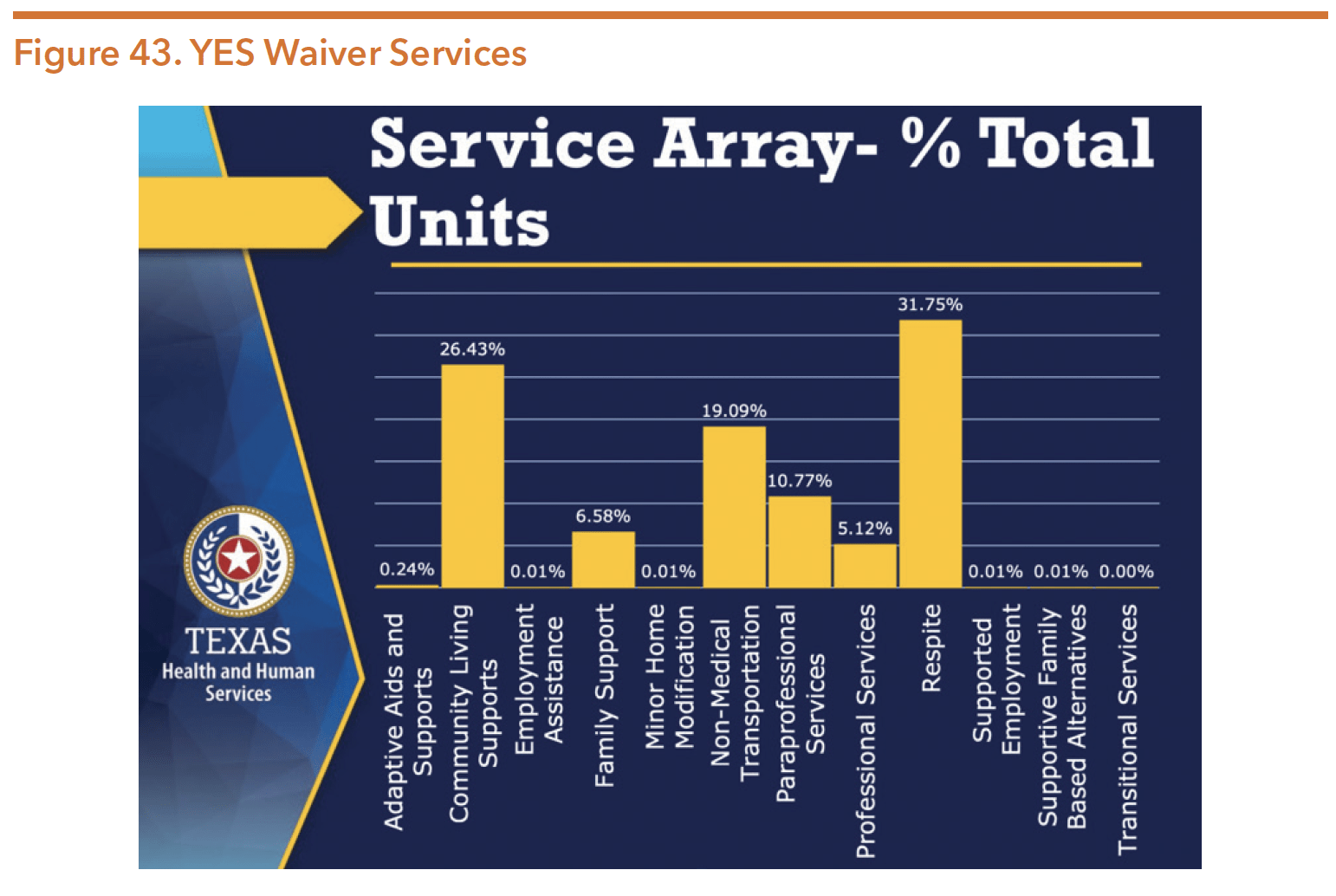

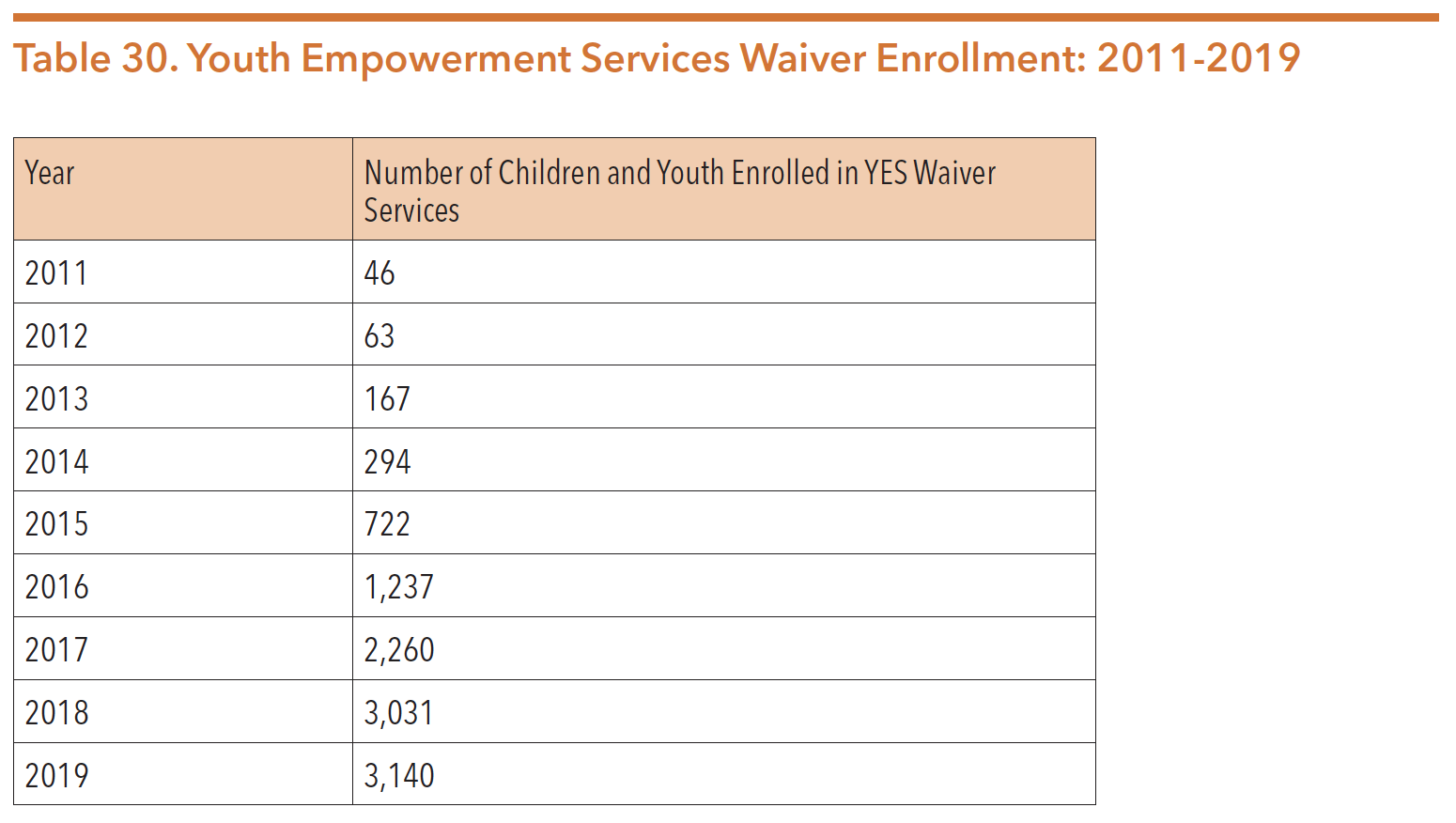

- Ensuring the ongoing success and improvement of services for children and youth available through the YES Waiver.

- Monitoring efforts of the state hospital redesign to ensure a comprehensive continuum of supports and services.

- Improving individual outcome performance measures to focus more on behavioral health outcomes and patient-centered recovery, and less on easy-to-measure outputs.

- Expanding access to coordinated specialty care teams for individuals experiencing first episode psychosis.

- Addressing the RTC bed wait list of children experiencing serious emotional disturbances (SEDs) who are at risk of being relinquished into the custody of Child Protective Services in order to receive mental health treatment.

- Coordinating cross-agency efforts to address the mental health needs of individuals with intellectual disabilities.

- Improving access to trauma-informed training across HHSC divisions specific to children and adults with intellectual disabilities.

- Accessing crisis services, including emergency respite.

- Implementing systems-wide trauma-informed care, positive behavior interventions and supports, and person-centered recovery-focused practices.

- Improving mental health and substance use services in state-supported living centers and community-based waiver programs.

- Improving wait list time for inpatient and community-based mental health and substance use services.

- Ensuring access to broadband and needed technology for telehealth and telemedicine

- Ensuring access to mental health and substance use services through telehealth and telemedicine, and across the state, particularly in rural and low-income areas; ensuring parity with in-person services and allowing the use of audio-only telephone

- Addressing the behavioral health needs of pregnant and postpartum women.

- Improving availability to affordable, safe, and supportive housing for individuals living with mental health and/or substance use conditions.

- Ensuring access to appropriate recovery support services for individuals receiving medication-assisted treatment (MAT).

- Monitoring the implementation of the All Texas Access project and its’ regional plans addressing mental health services.

- Expanding eligibility for Medicaid reimbursed peer support services to youth under the age of 21.

- Improving recovery-oriented supports with increased availability of peer recovery coaches, Recovery Community Organizations (RCOs), and community-based aftercare.

- Increasing access to school and community-based substance use prevention programs.

Fast Facts

- The 2020-2021 HHSC appropriation of all funds was over $76 billion and comprised 30 percent of the state’s entire budget.

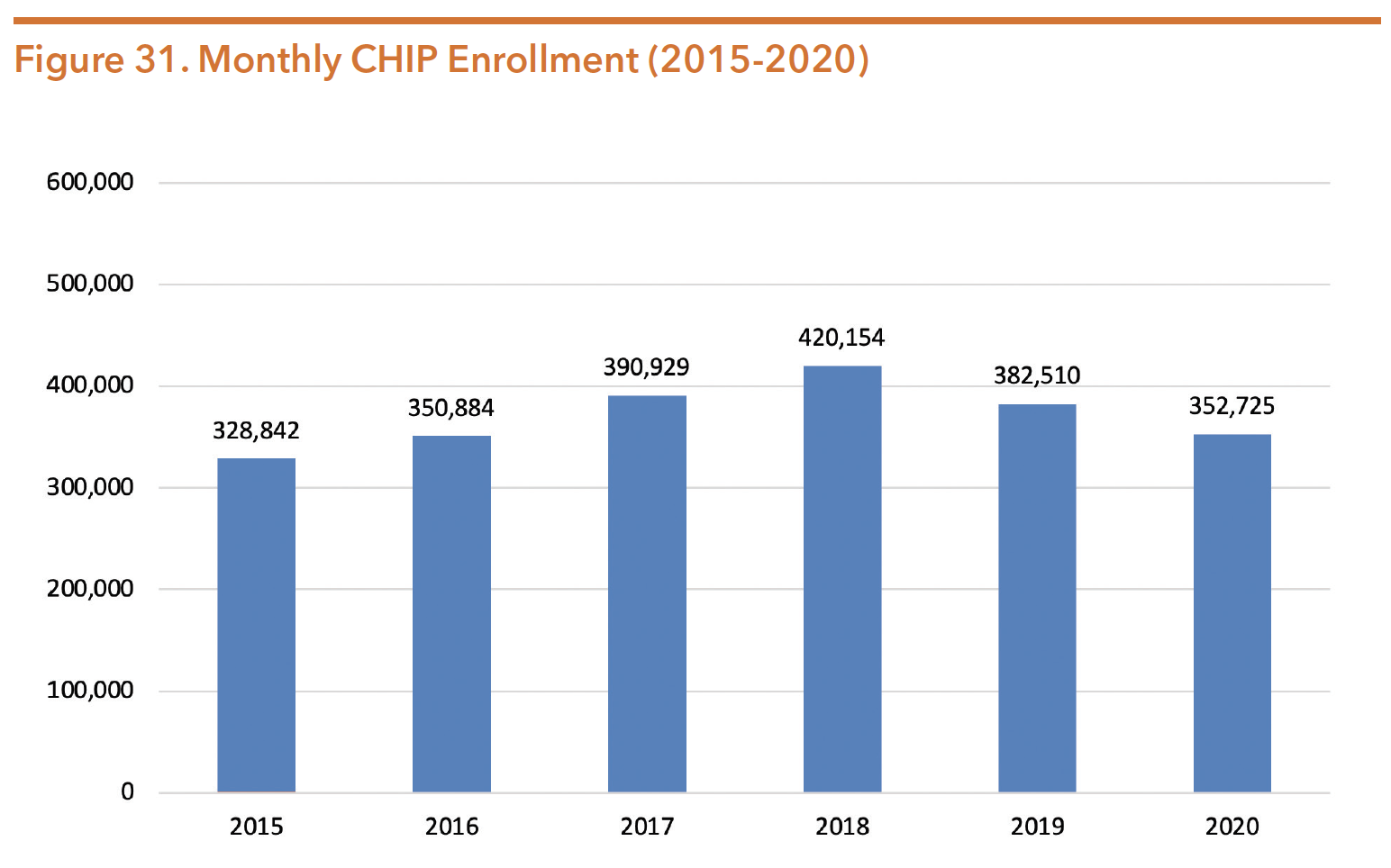

- In January 2020, 3,870,036 individuals were enrolled in Medicaid and 352,725 enrolled in CHIP in Texas.

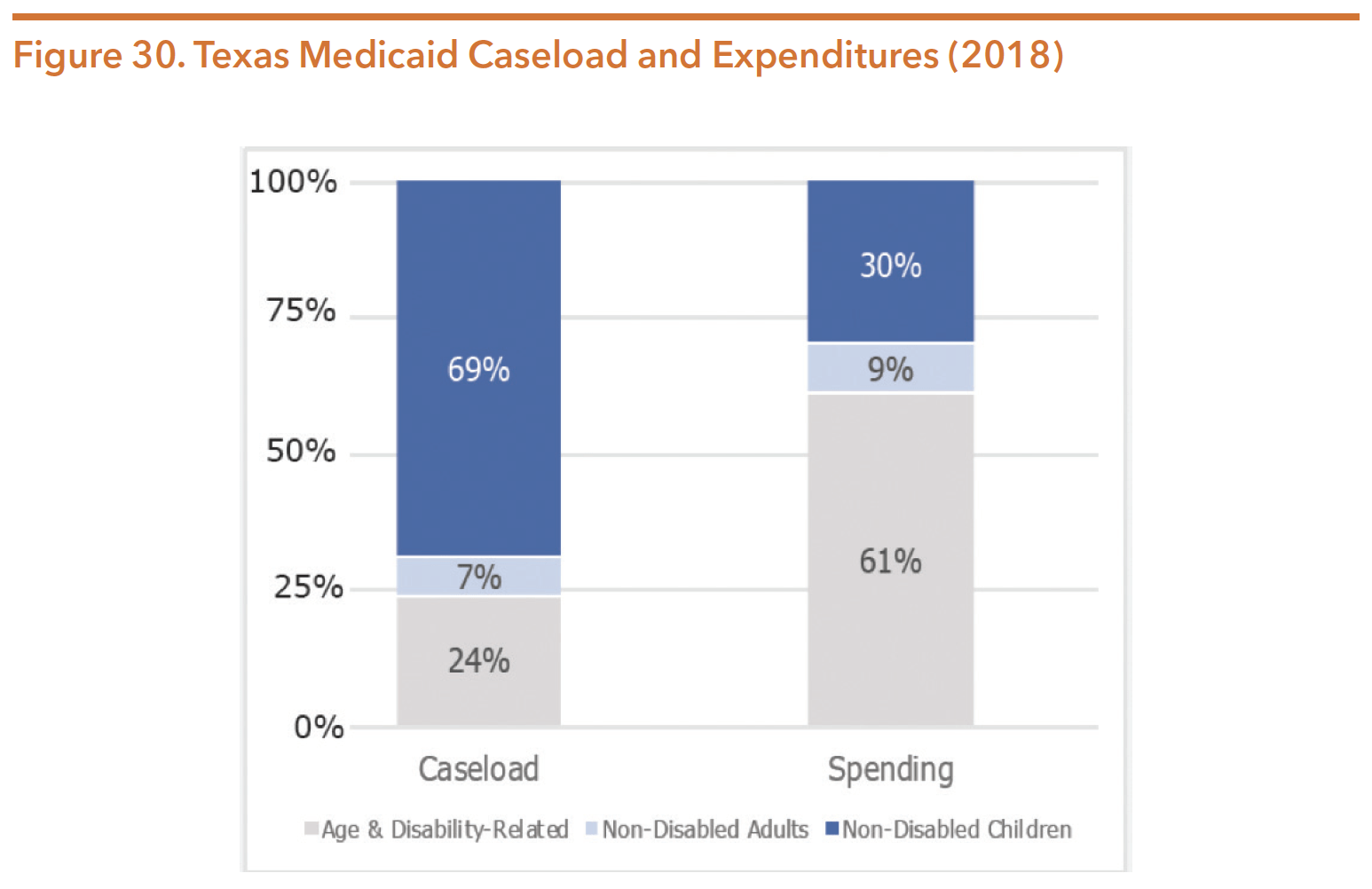

- Children without disabilities account for 69 percent of Medicaid enrollment but only 30 percent of program spending on direct healthcare services.

- In 2018, Medicaid covered approximately 53 percent of births, 44 percent of children across the state, and 62 percent of nursing home residents in Texas.

- Texas has 73 Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) serving over 1.4 million Texans at more than 300 sites statewide.

- The population growth in Texas between 2010 and 2019 (15.3 percent) was more than double the national average (6.3 percent), resulting in increased demand for HHSC-funded services.

- As of June 2020, Texas had only met about 36 percent of the state’s need of mental health professionals and 214 counties were designated as either full or partial Health Professional Shortage Areas for Mental Health (HPSA-MH).

- As of August 2020, Texas has 506 people trained as certified mental health peer specialists (MHPS), 246 certified recovery support peer specialists (RSPS), and 222 peer specialist supervisors (PSS), enabling them to use their lived experiences with behavioral health issues to help recipients of HHSC-funded services.

- In 2018, over 12 million adults in the United Stated were living with a co-occurring substance use and mental health condition.

- Almost half of individuals who live with a mental health condition also live with a substance use condition.

- Over 60 percent of adolescents receiving community-based substance use treatment also meet diagnostic criteria for a mental illness.

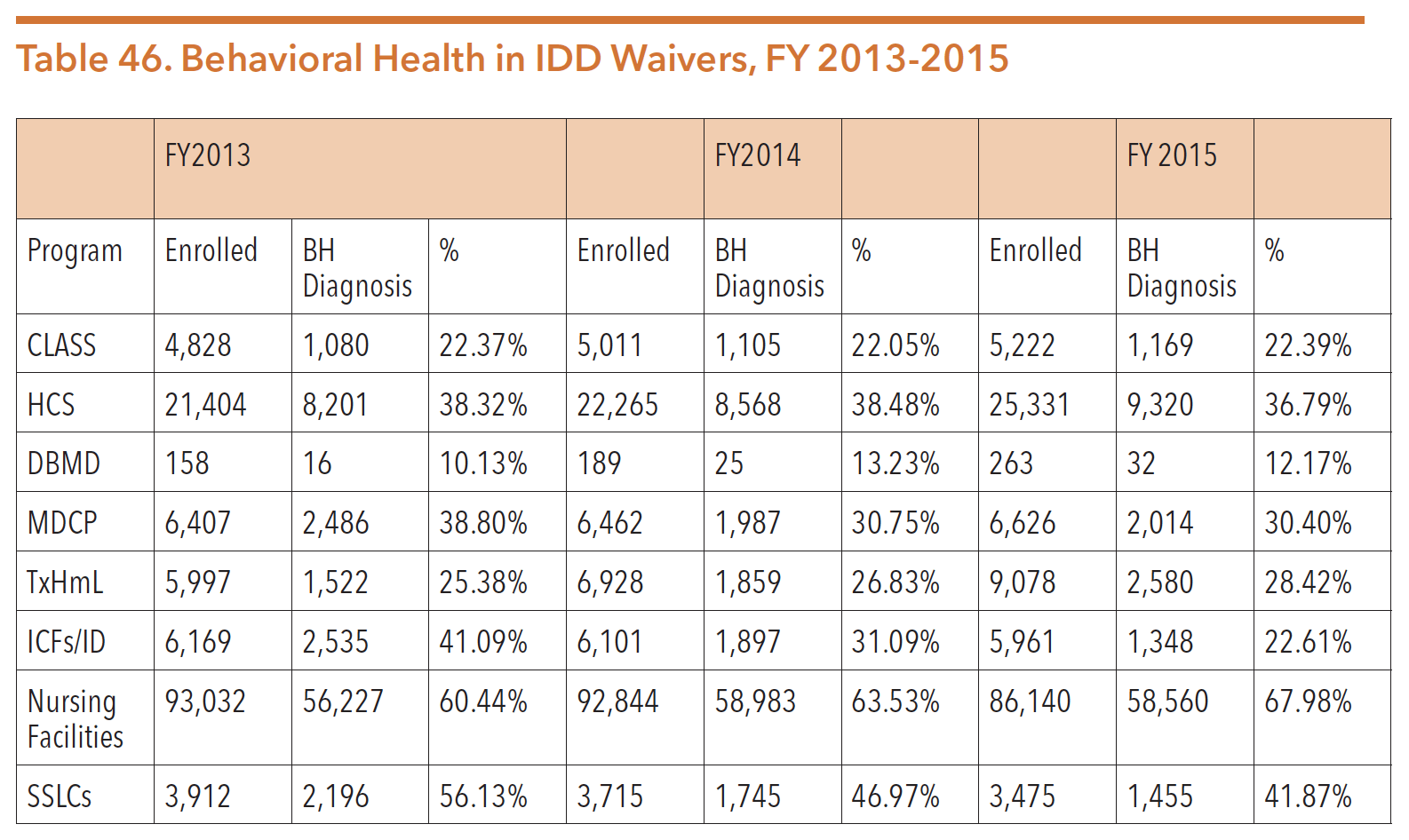

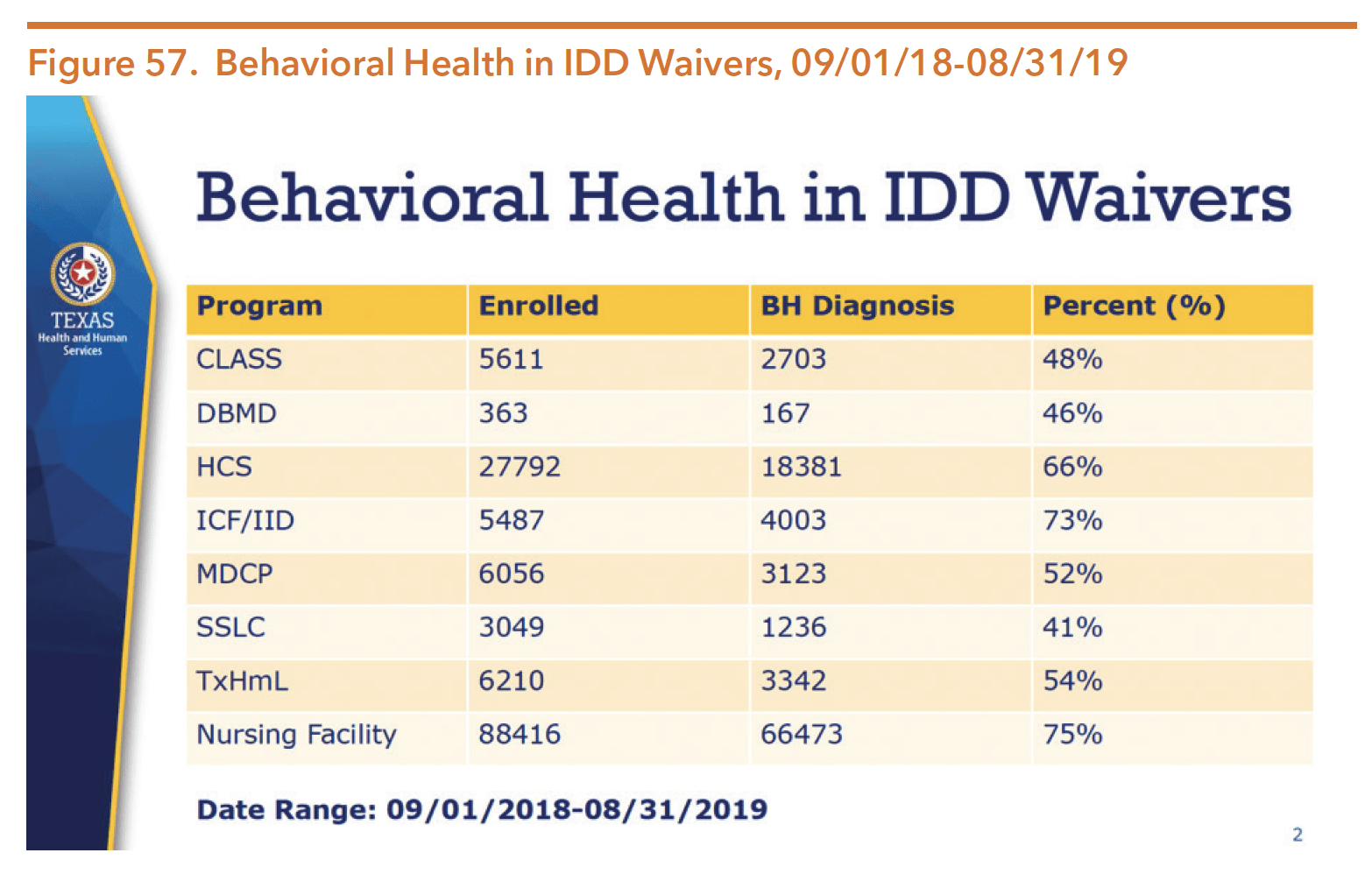

- It is estimated that as many as 30 to 40 percent of persons with intellectual disabilities are diagnosed with a mental health condition and are three to five times more likely to have a co-occurring mental health condition than the general population.

- Children with intellectual and other developmental disabilities (IDD) are more likely to have experienced traumatic events when compared to those without disabilities. However, the known rate of abuse may be higher due to underreporting or lack of recognition by family and other caregivers.

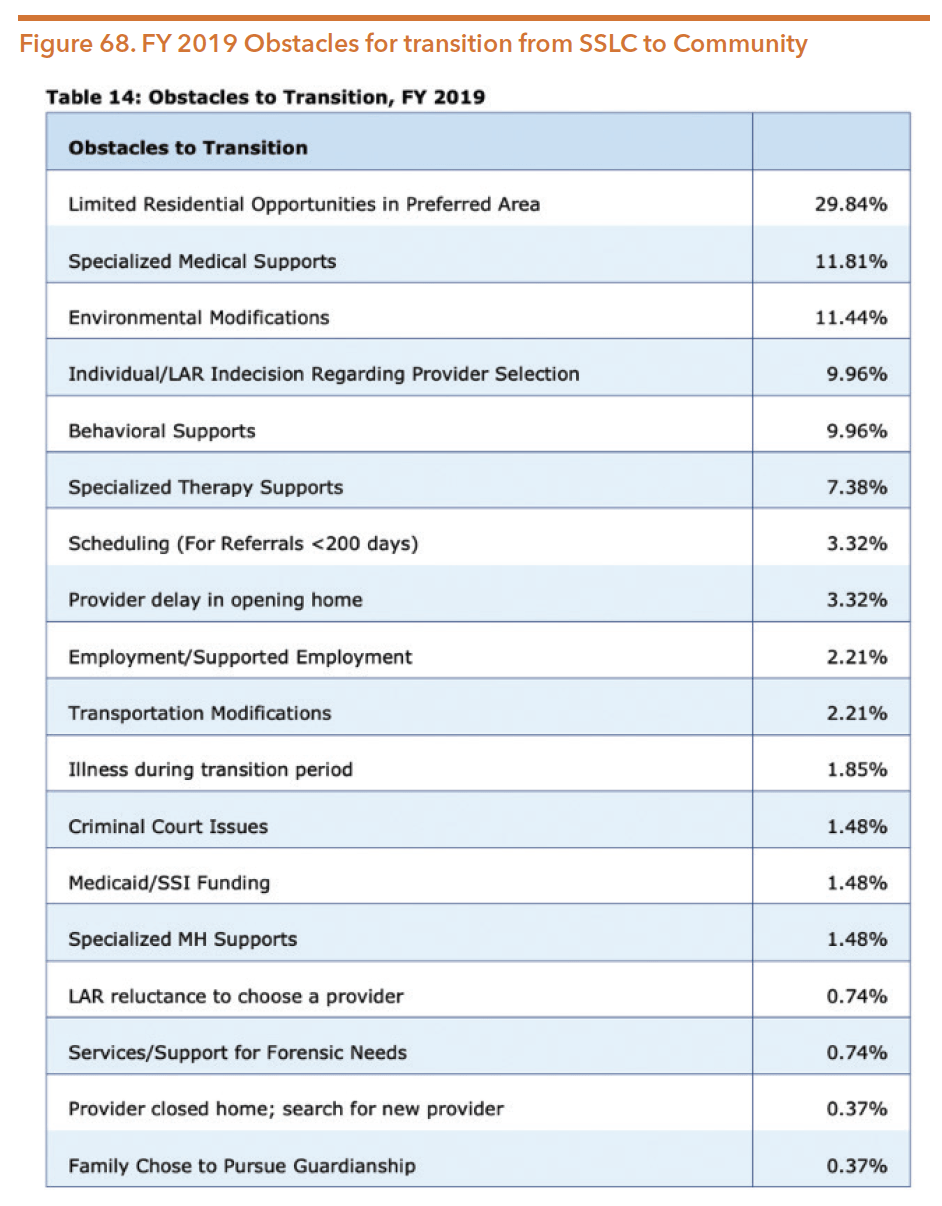

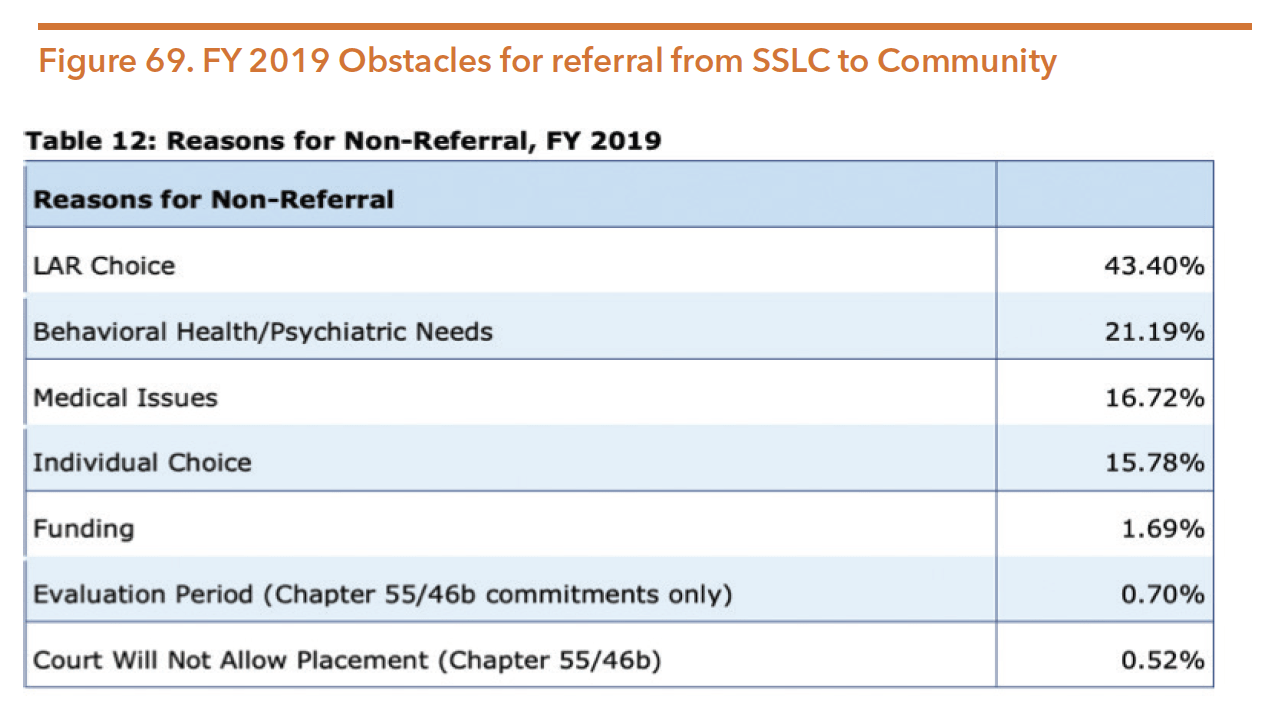

- Individuals with IDD who have a dual diagnosis or who present behavioral “challenges” are more likely to be institutionalized and are often the last to be released to a community-based setting. Additionally, community services and supports are frequently incapable of meeting the behavioral health needs of these individuals, leading to less successful outcomes when transitioning into the community.

- Individuals aged 18-25 are at the highest risk of overdose as they are more likely than any other age group to misuse a prescription medication, use an illicit drug, or use heroin.

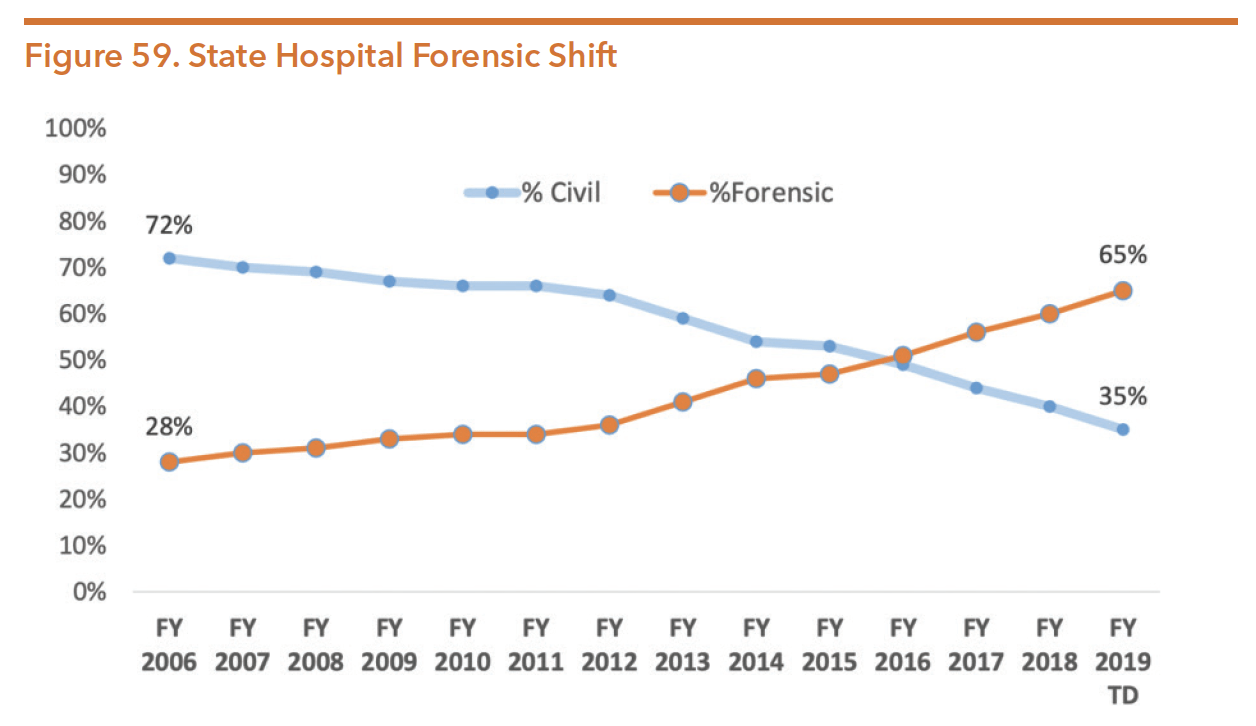

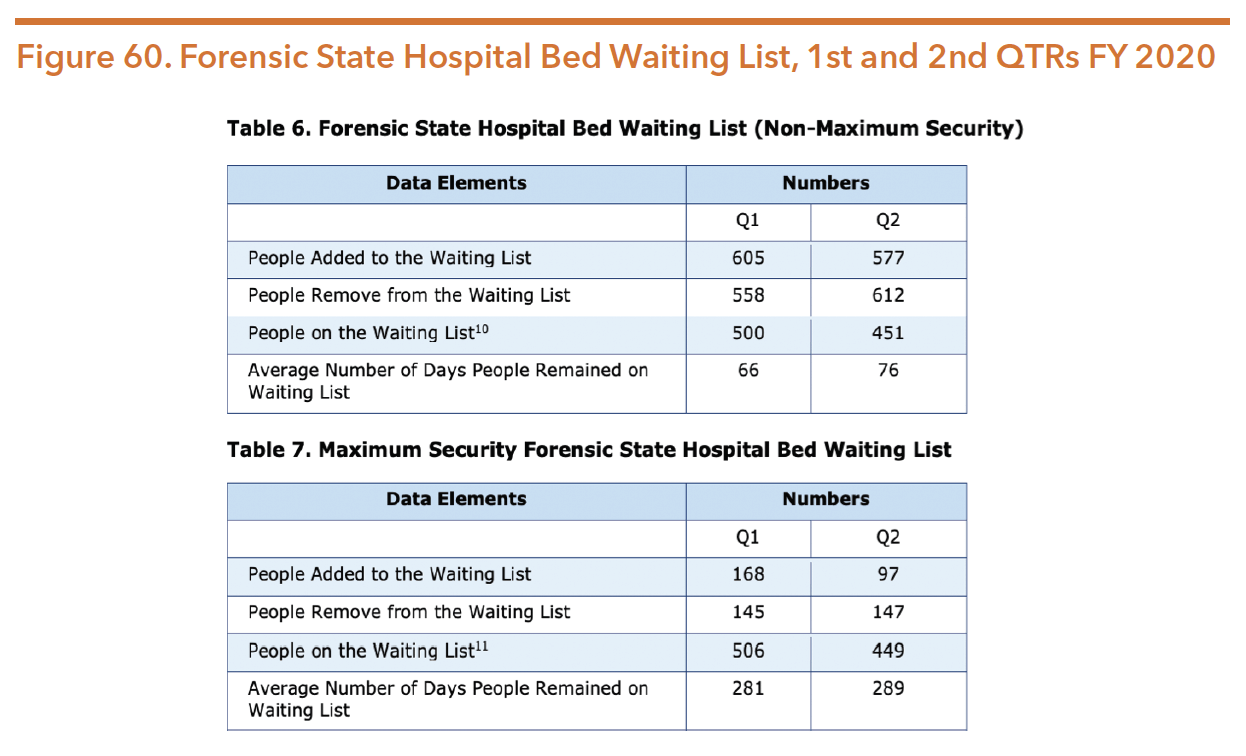

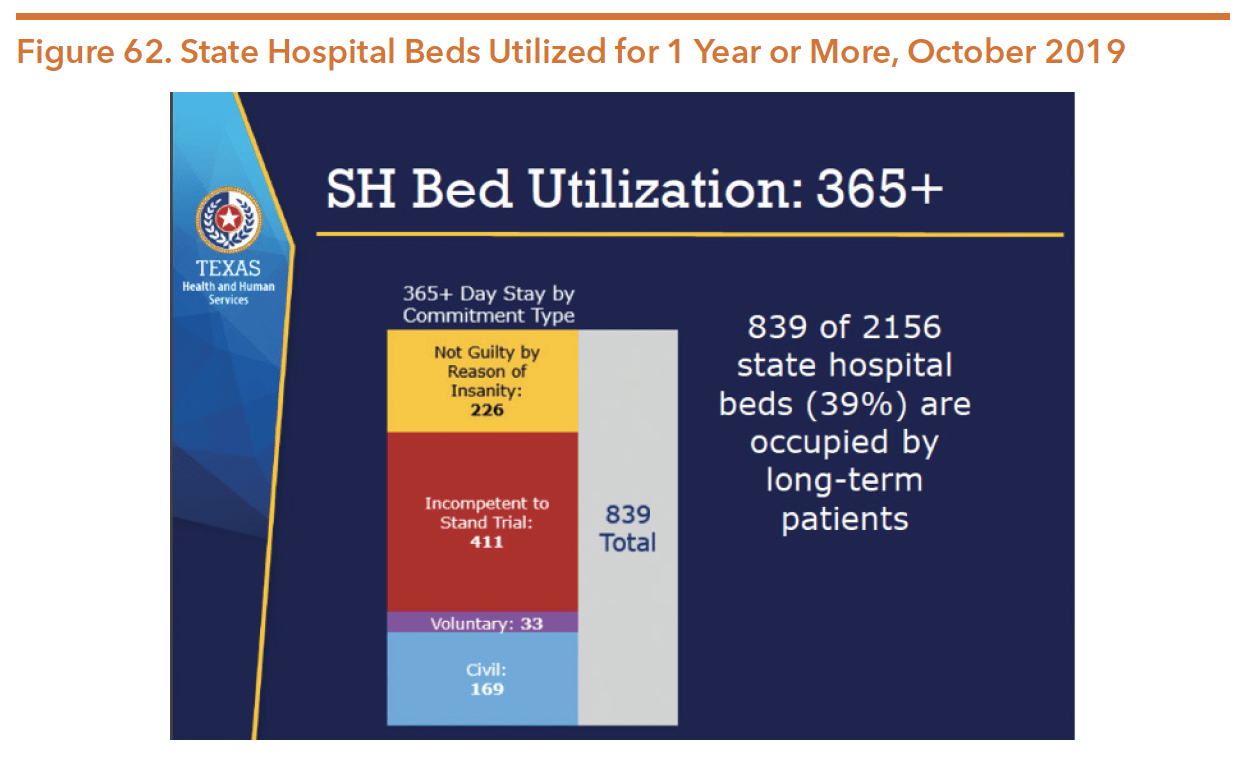

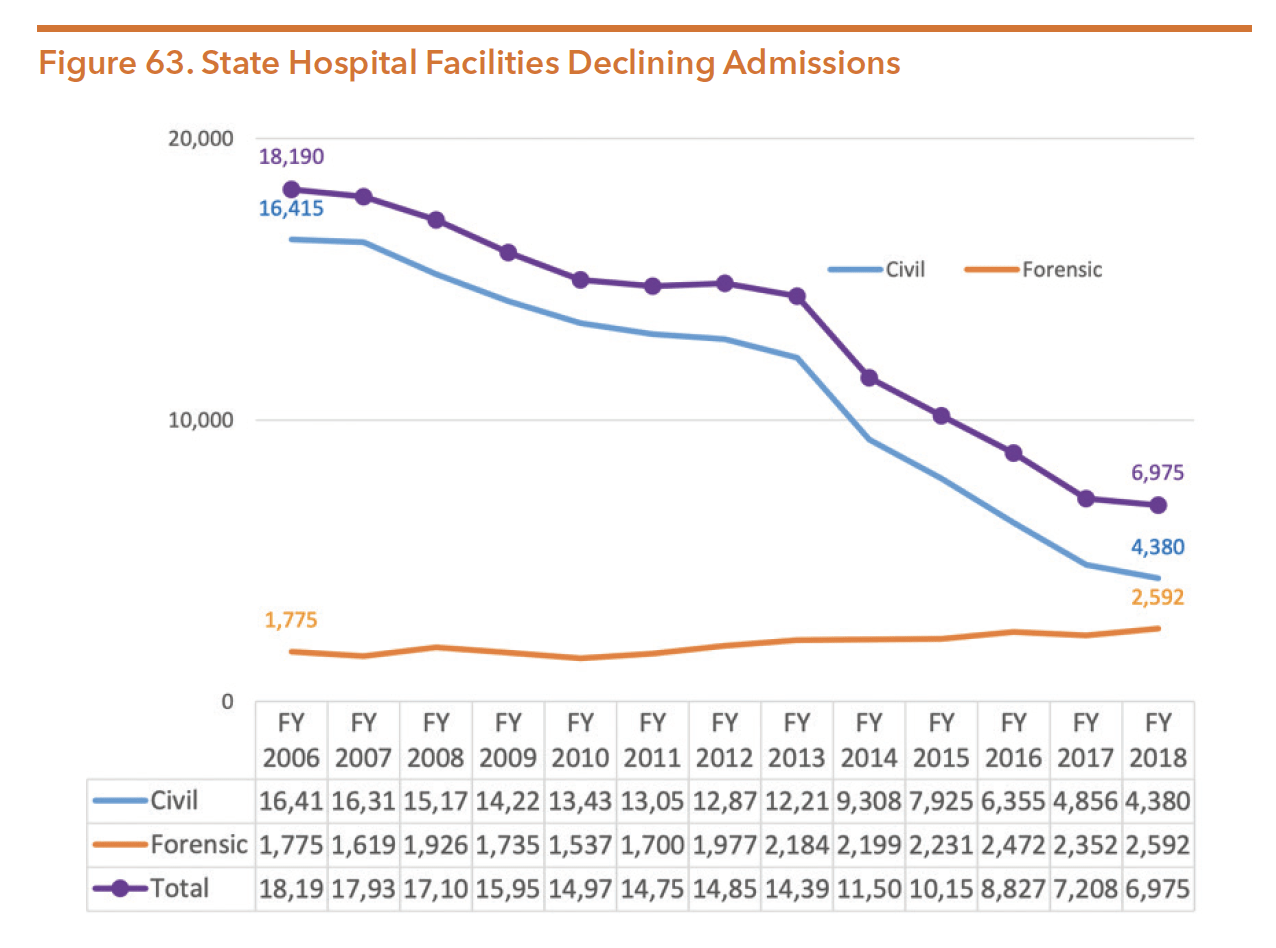

- As of April 2020, there were 449 individuals waiting for a maximum-security forensic state hospital bed, with the average of 289 days on the waiting list.

- As of April 2020, there were 451 individuals waiting for a non-maximum-security forensic state hospital bed, with the average of 76 days on the waiting list.

HHSC Acronyms

- ACA – Affordable Care Act

- ACT – Assertive Community Treatment

- ANSA – Adult Needs and Strengths Assessment

- APS – Adult Protective Services

- APS PI – Adult protective services provider investigations

- ASD – Autism spectrum disorders

- BHAC – Behavioral Health Advisory Committee

- CANS – Child and Adolescent Needs and Strength Assessment

- CBT – Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

- CHIP – Children’s Health Insurance Program

- CIHCP – County Indigent Health Care Program

- CIL – Centers for Independent Living

- CLOIP – Community living options information process

- CMS – Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services

- COPSD – Co-occurring psychiatric and substance abuse disorders services

- COVID- 19 – Coronavirus disease of 2019

- CPS – Child Protective Services

- CRS – Comprehensive rehabilitation services

- CSC – Coordinated specialty care

- DADS – Department of Aging and Disability Services

- DARS – Department of Assistive and Rehabilitative Services

- DDS – Disability Determination Services

- DFPS – Department of Family and Protective Services

- DSM-V – Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition

- DSRIP – Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment

- ECI – Early Childhood Intervention

- IDEA – Individuals with Disabilities Education Act

- FEP – First Episode Psychosis

- FFCC – Former foster care children

- FMAP – Federal medical assistance percentage

- FPG – Federal poverty guidelines

- FPL – Federal poverty level

- FQHC – Federally Qualified Health Center

- GAO – Government Accounting Office

- GR – General revenue

- HCBS-AMH – Home and Community-based Services – Adult Mental Health

- HCS – Home and community-based services

- HCSSA – Home and community support services agency

- HEDIS – Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set

- HHS – Health and Human Services

- HHSC – Health and Human Services Commission

- HPSA – Health professional shortage area

- HPSA-MH – Health professional shortage area for mental health

- ICF/IDD – Intermediate care facility-intellectual and developmental disabilities

- ICM – Intensive case management

- ICR – Inpatient competency restoration

- IDD – Intellectual and other developmental disabilities

- IL – Independent living

- IMD – Institutions for Mental Diseases

- IST – Incompetent to stand trial

- JBCR – Jail-based competency restoration

- LAR – Legally authorized representative

- LBB – Legislative Budget Board

- LBHA – Local behavioral health authority

- LIDDAs – Local intellectual/developmental disability authorities

- LMHAs – Local mental health authorities

- LOC – Level of care

- LOC-A – Level of care-authorized

- LOC-EO – Level of care-early onset

- LOC-R – Level of care-recommended

- LOS – Length of stay

- LTSS – Long-term services and supports

- MAT – Medication-assisted treatment

- MCO – Managed care organization

- MCOT – Mobile crisis outreach teams

- MDCP – Medically Dependent Children’s Program

- MOU – Memorandum of Understanding

- MOE – Maintenance of Effort

- MSU – Maximum security unit

- MTFCY – Medicaid for Transitioning Foster Care Youth

- NQTLs – Non-quantitative treatment limits

- NWI – National Wraparound Initiative

- OCR – Outpatient competency restoration

- ODPC – Office of Disability Prevention for Children

- OSAR – Outreach, screening, assessment, and referral center

- PASRR – Preadmission screening and resident review

- QTLs – Quantitative treatment limits

- RHP – Regional healthcare partnership

- ROSC – Recovery-oriented systems of care

- RSS – Recovery support services

- RTC – Residential treatment center

- SAMHSA – Substance Use and Mental Health Services Administration

- SBIRT – Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment

- SCI – Spinal cord injury

- SED – Serious emotional disturbance

- SH – State hospital

- SMI – Serious mental illness

- SNAP – Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

- SOC – Systems of care

- SPA – Medicaid state plan amendment

- SPMI – Serious and persistent mental illness

- SSA – Social Security Administration

- SSDI – Social Security Disability Income

- SSI – Supplemental Security Income

- SSLC – State-supported living center

- STAR – State of Texas Access Reform

- STAR Health – State of Texas Access Reform program for children in CPS system

- STAR Kids – State of Texas Access Reform program for children with disabilities eligible for SSI

- STAR+Plus – State of Texas Access Reform program that includes long-term services and supports

- SUD – Substance use disorder

- TANF – Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

- TAS – Transition assistance services

- TBI – Traumatic brain injury

- TCCP – Texas Code of Criminal Procedures

- TDCJ – Texas Department of Criminal Justice

- TDHCA – Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs

- TDI – Texas Department of Insurance

- TEA – Texas Education Agency

- TJJD – Texas Juvenile Justice Department

- TMHP – Texas Medicaid Healthcare Partnership

- TOPDD – Texas Office of Prevention of Developmental Disabilities

- TRI – Texas Recovery Initiative

- TRR – Texas Resiliency and Recovery

- TVC – Texas Veterans Commission

- TWC – Texas Workforce Commission

- YES Waiver – Youth Empowerment Services Waiver

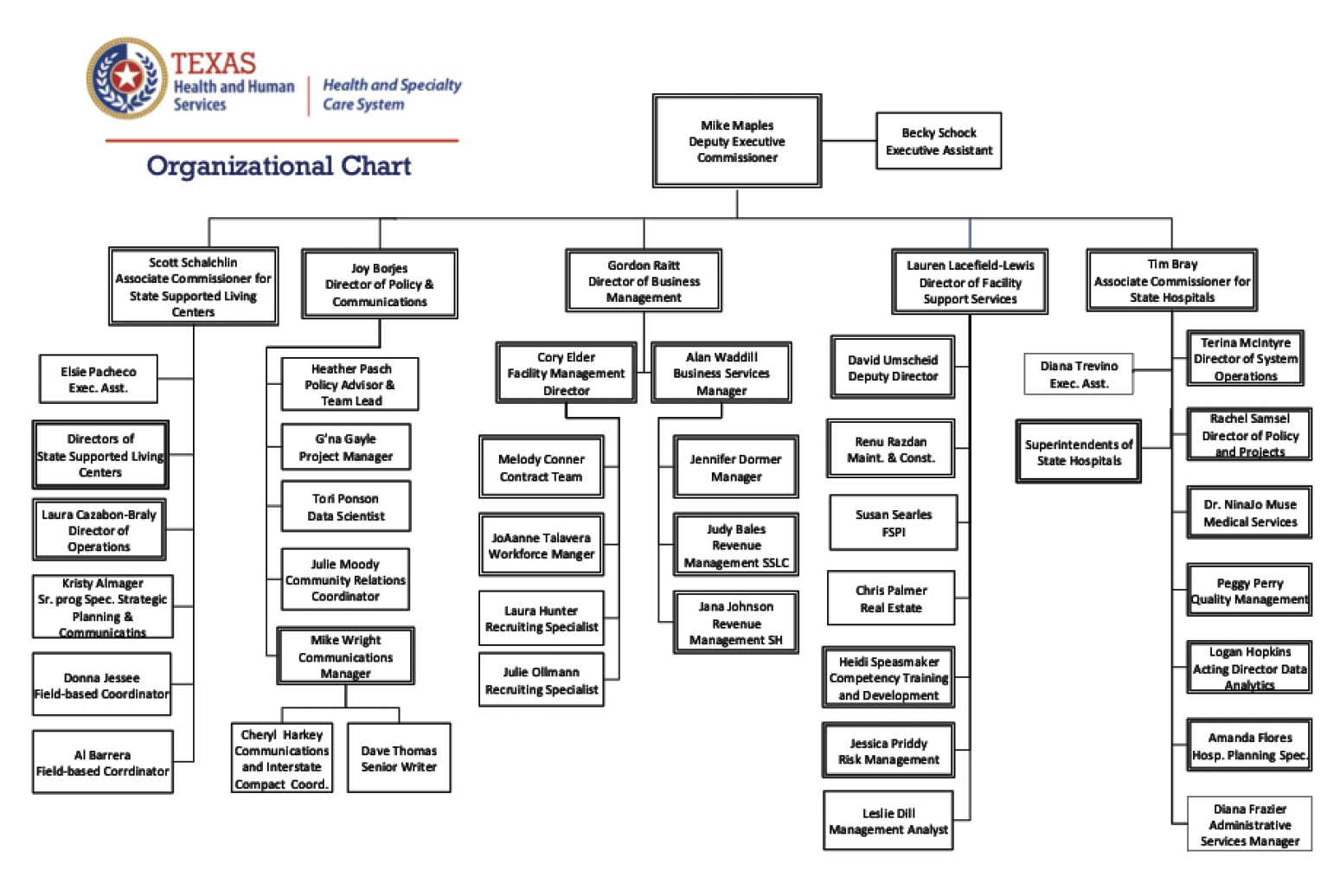

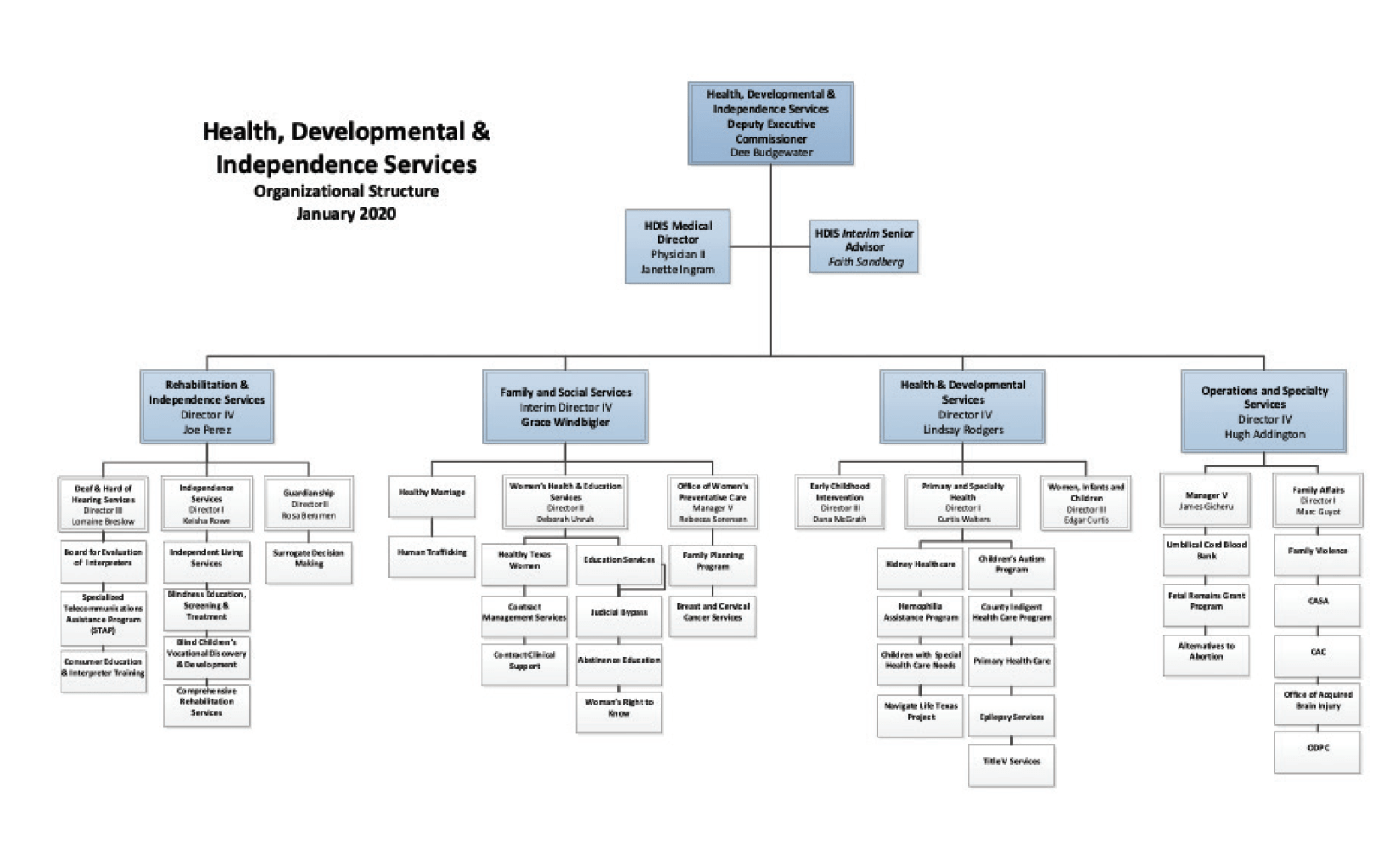

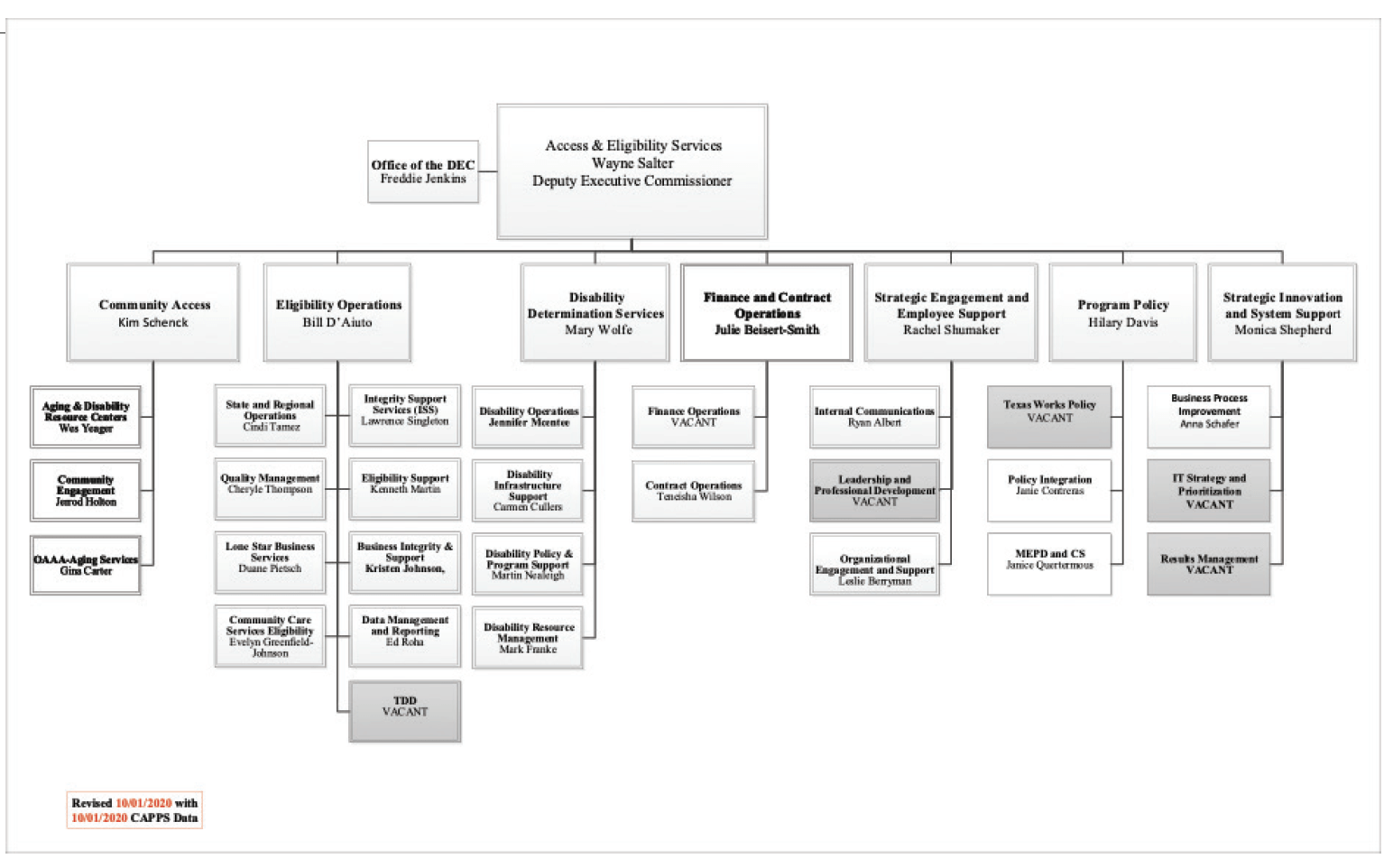

Texas Health and Human Services System Organizational Chart

Source: Texas Health and Human Services Commission. (2020, October 1). Health and Human Services system organizational chart [PDF file]. Retrieved from https://hhs.texas.gov/sites/default/files/documents/about-hhs/ leadership/hhs-org-chart.pdf

Overview

The Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) is the umbrella agency providing a multitude of services and programs to Texans. HHSC programs and services include Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), long-term services and supports, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) food benefits, temporary assistance for needy families (TANF) cash benefits, mental health and substance use services, and services for older Texans, women, and people with disabilities. Services are delivered through a complex system of programs and benefits. HHSC also oversees certain regulatory functions such as nursing facility licensing and credentialing, licensing of childcare providers, certain professional licensing and certification, and management of state supported living centers and state psychiatric facilities.

The Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) is also under the HHSC agency umbrella but operates as a separate department. DSHS focuses on public health functions such as vital statistics, compiling and disseminating health data, prevention of chronic and infectious diseases, maternal and child health, laboratory testing, and licensing and regulating certain facilities and operations.

Over the last 17 years, the Texas Health and Human Services system has undergone extensive reorganization in an attempt to produce a more efficient, effective, and responsive system. The HHSC transformation began in 2003 as the umbrella agency overseeing multiple programs and departments. After the 2015 Sunset Review Commission review and subsequent recommendations through SB 200 (85th, Nelson/Price), reorganization efforts prioritized agency consolidation. Several client services were transferred to HHSC, including state hospital inpatient services, SSLCs, and some regulatory and administrative services. This transfer eliminated both the Department of Assistive and Rehabilitative Services (DARS) and the Department of Aging and Disability Services (DADS). Additionally, behavioral health and regulatory functions (previously administered by DSHS and the Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS)), the Office of Mental Health Coordination, and the Forensic Director position were transferred to HHSC over the next few years. As transformation continued, DFPS became an independent agency, and the Health and Human Services system consequently became solely comprised of HHSC and DSHS.

Additionally, the HHSC Executive Council was established during the transition. The primary purpose of the council is to obtain public input and to advise the HHSC executive commissioner on policies relating to the health and human services system. Information on the HHSC Executive Council is available at https://hhs.texas.gov/about-hhs/leadership/councils/ health-human-services-commission-executive-council.

Transformation planning and implementation continues within the HHS system and is led by the Transformation, Policy and Performance Office, which reports to the Chief Policy Officer. The Chief Policy Officer reports directly to the executive commissioner and is responsible for innovation, performance management, policy development, and data analysis.

The transformation of the HHS system is overseen by the Joint Health and Human Services Transition Legislative Oversight Committee. The committee is made up of four members of the Texas Senate, four members of the Texas House, three governor-appointed public members, and the HHSC Executive commissioner as an ex officio member. According to Chairwoman Nelson, the committee’s charges are to ensure easier access to services for individuals, remove blurred lines of authority, remove barriers to system-wide improvements, and improve overall efficiency.

Changing Environment

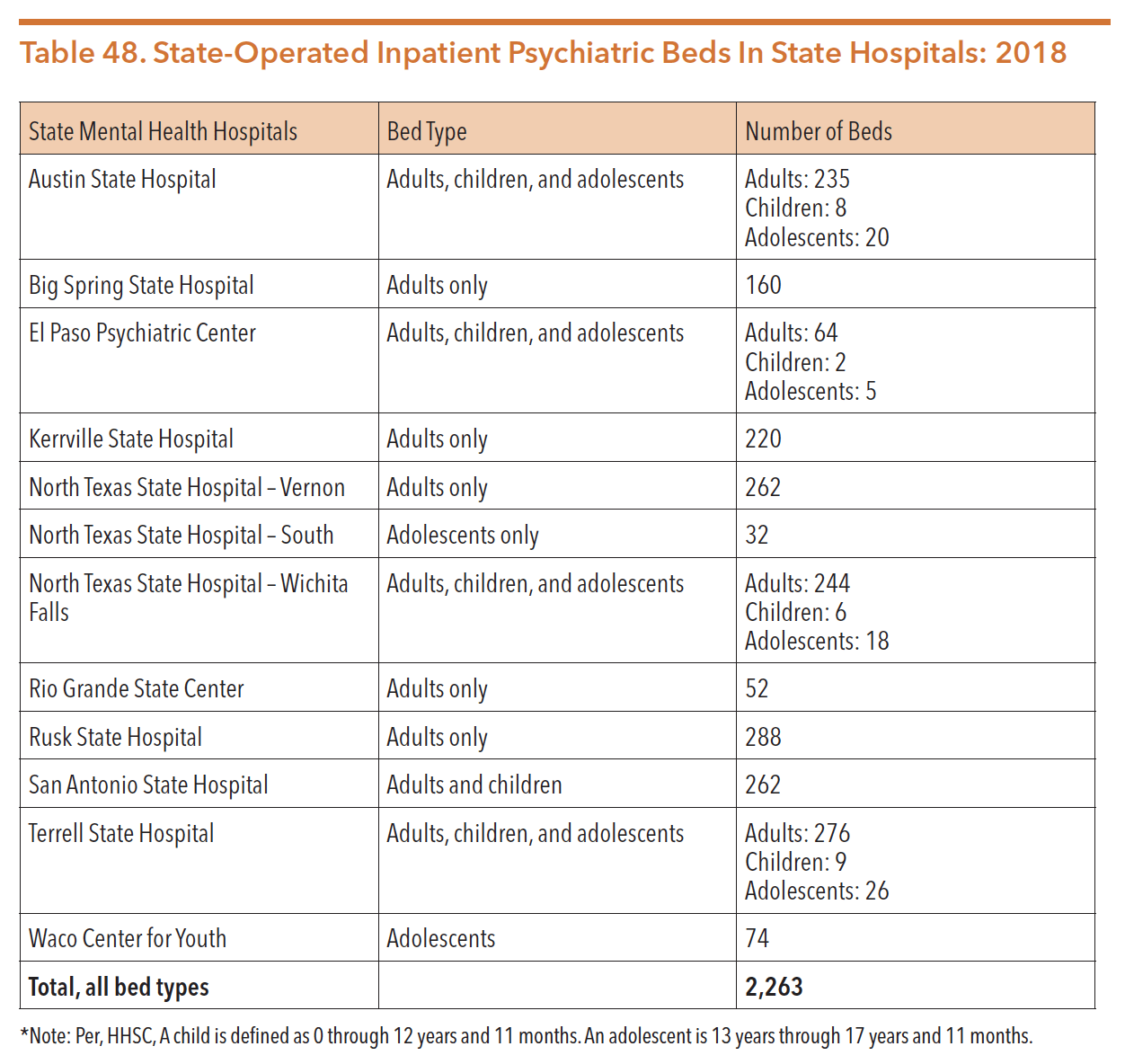

Prior to the Texas Legislature’s 86th session, leadership committed to prioritize major initiatives including school finance reform and local property taxes. Additionally, mental health and substance use continued to garner significant attention, with school safety/mental health and opioid use highlighted as important policy agenda. The Texas Legislature continued to invest resources to improve access to both adult and youth behavioral supports and services, address the mental health workforce shortage, and re-design the state’s hospital system. The investment made to continue the redesign and construction of inpatient mental health services is imperative to ensure that critical mental health services needed by Texans are available.

HB 1 (ZERWAS/NELSON) GENERAL APPROPRIATIONS TO HHSC FOR MENTAL HEALTH AND SUBSTANCE USE FUNDING

HB 1 funding for mental health and substance use supports and services administered by HHSC are allocated in Article II of the state’s budget. Additional funding information can be found in the Funding section of this guide. The legislature made a number of decisions to improve access to mental health and substance use services. Some highlights include:

- An appropriation to reduce waiting lists for mental health community-based services (Rider 20);

- An appropriation to maintain a mental health peer support re-reentry program (Rider 57);

- An increase in funds to women and children’s substance use treatment services (Rider 64);

- Funding to increase the number of RTC beds available to avoid child relinquishment due to the needs of intensive mental health services (Rider 65);

- Continued funding of grants created through HB 13 (85th, Price/Schwertner) and SB 292 (85th, Huffman/Price) focused on mental health supports and services for communities and justice-involved individuals; and

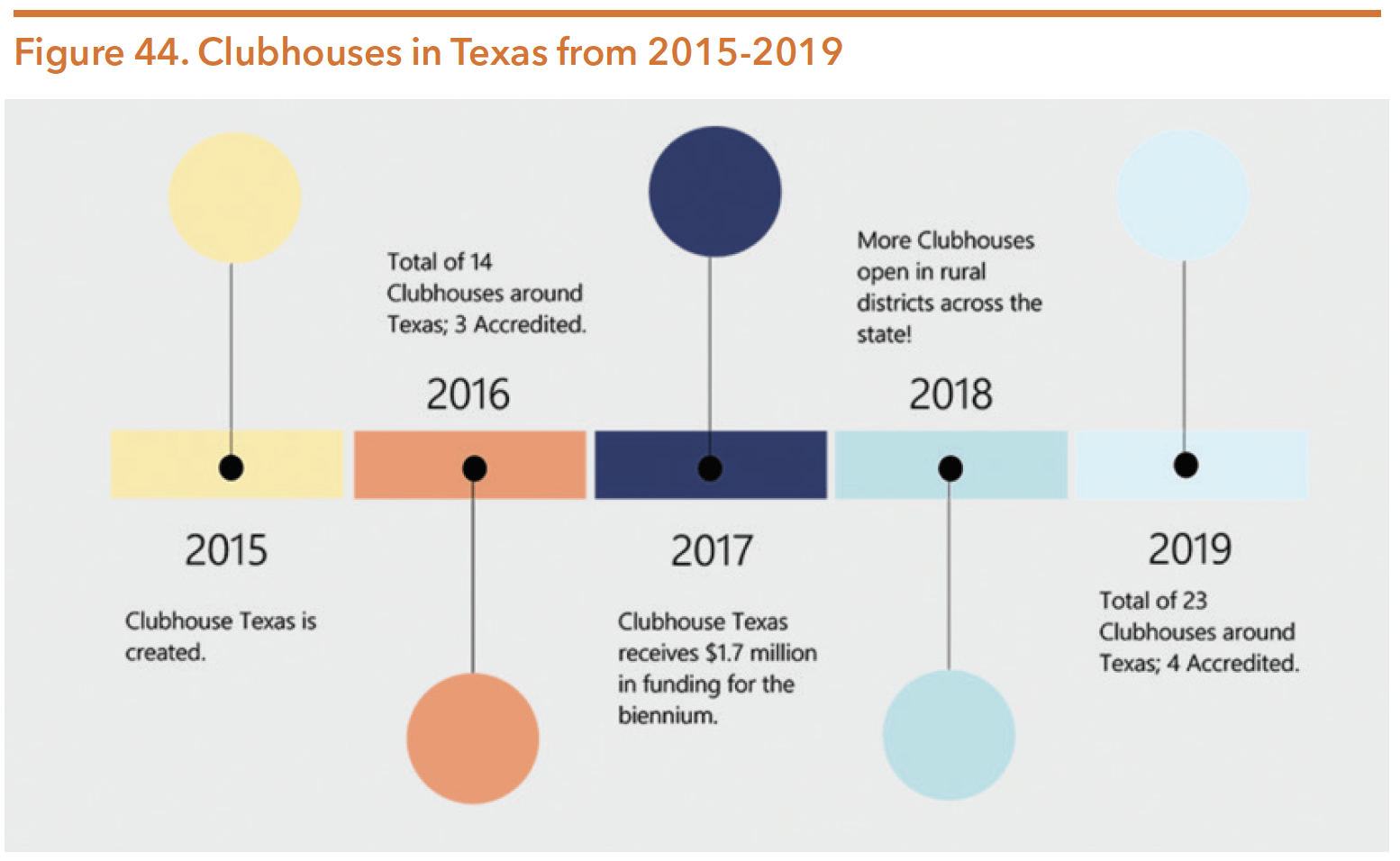

- Continued funding for clubhouses across the state (Rider 65).

SB 500 (NELSON/ZERWAS) – SUPPLEMENTAL APPROPRIATIONS TO HHSC

SB 500 appropriated over $450 million for renovations and construction on state hospitals across the state.

SB 11 (TAYLOR/BONNEN) – TEXAS CHILD MENTAL HEALTH CONSORTIUM

SB 11 was filed to address safe and supportive schools, with mental health as one component of the legislation. It also includes provisions related to school hardening strategies and staff training on how to respond during an emergency.

Additionally, SB 10 (Nelson) was amended onto this bill through swift legislative action near the end of the legislative session. SB 10 created the Texas Children’s Mental Health Care Consortium (Consortium). The goal is to leverage institutions of higher education’s expertise and capacity to enhance collaboration between institutions, improve access to behavioral health care for youth, and address the youth psychiatric workforce shortage. The bill creates four major initiatives: Child Psychiatry Access Network (CPAN), the Texas Child Access Through Telemedicine (TCHATT), Child Psychiatry Workforce Expansion, and Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Fellowship. To implement and establish the initiatives, the Texas Legislature appropriated $99 million.

More details on SB 11 and other school mental health legislation can be found in The TEA Section of this guide, and The Hogg Foundation’s School Climate Legislation from the 86th Legislative Session brief found at https://hogg.utexas. edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/FINAL_86th-Lege_Policy-Brief_School-Climate. pdf.

HB 253 (FARRAR/KOLKHORST) POSTPARTUM DEPRESSION STRATEGIC PLAN

HB 253 directs HHSC to create develop and implement a five-year strategic plan to improve access to postpartum depression (PPD) screening, referral, treatment, and support services. The strategic plan is required to include strategies to:

- Increase awareness among state-administered program providers who may serve women who are at risk of or are experiencing PPD about the prevalence and effects of PPD on outcomes for women and children;

- Establish a referral network of community-based mental health providers and support services addressing PPD;

- Increases women’s access to formal and informal peer support services, including access to certified peer specialists who have received additional training related to PPD;

- Raise public awareness of and reduce the stigma related to PPD; and

- Leverage sources of funding to support existing community-based PPD screening, referral, treatment, and support services.

SB 633 (KOLKHORST/LAMBERT) TEXAS ALL ACCESS PROJECT

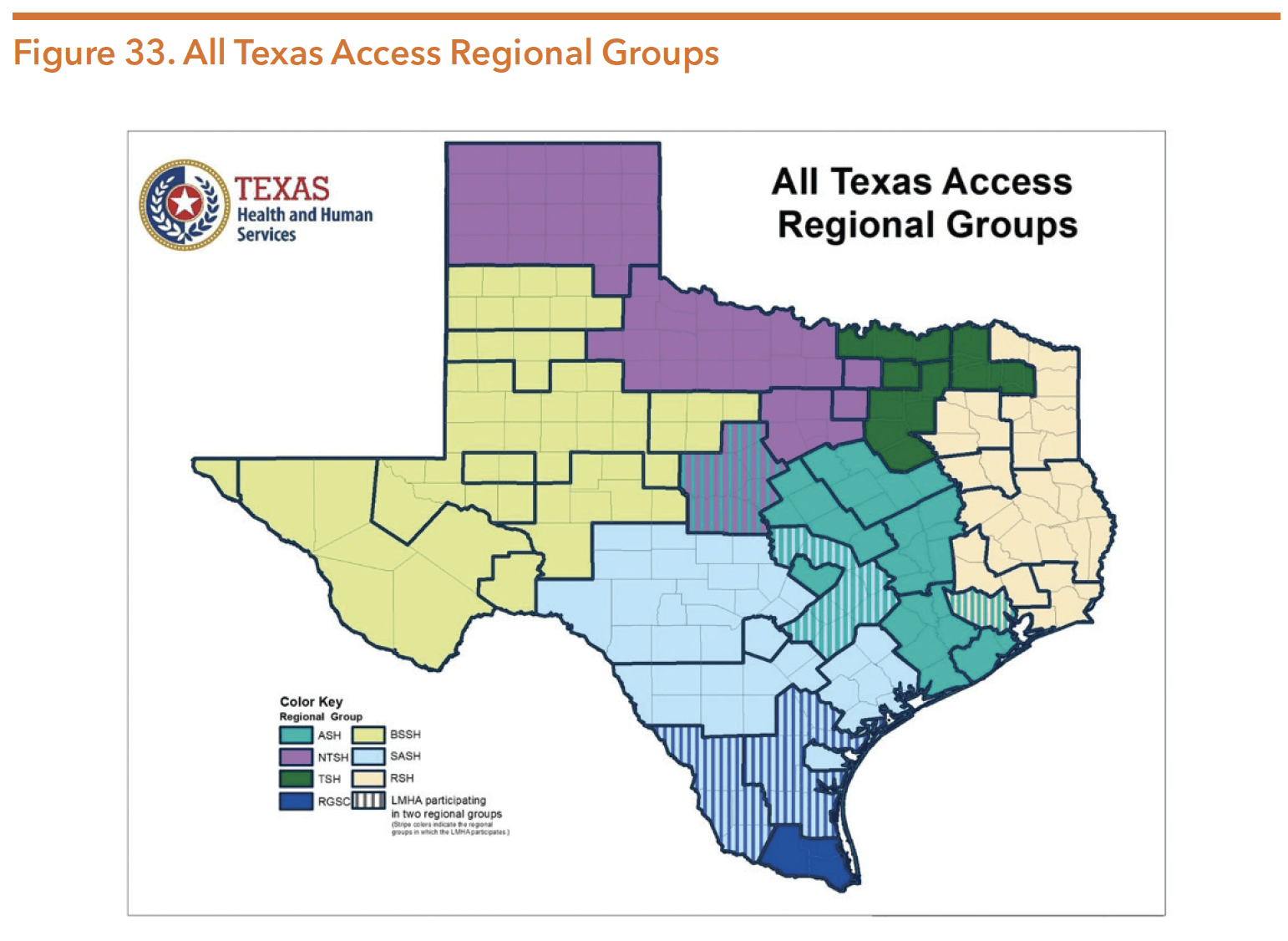

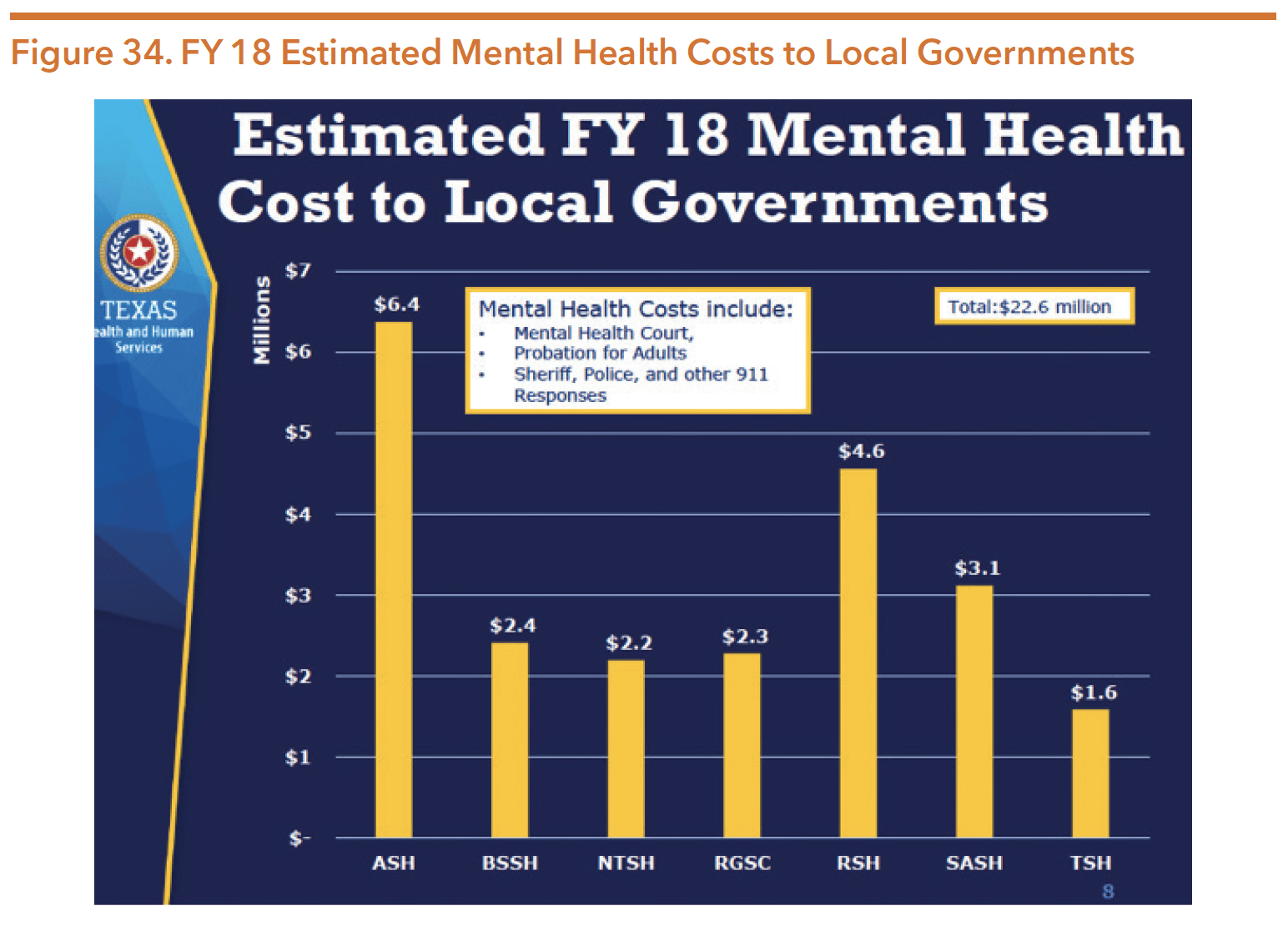

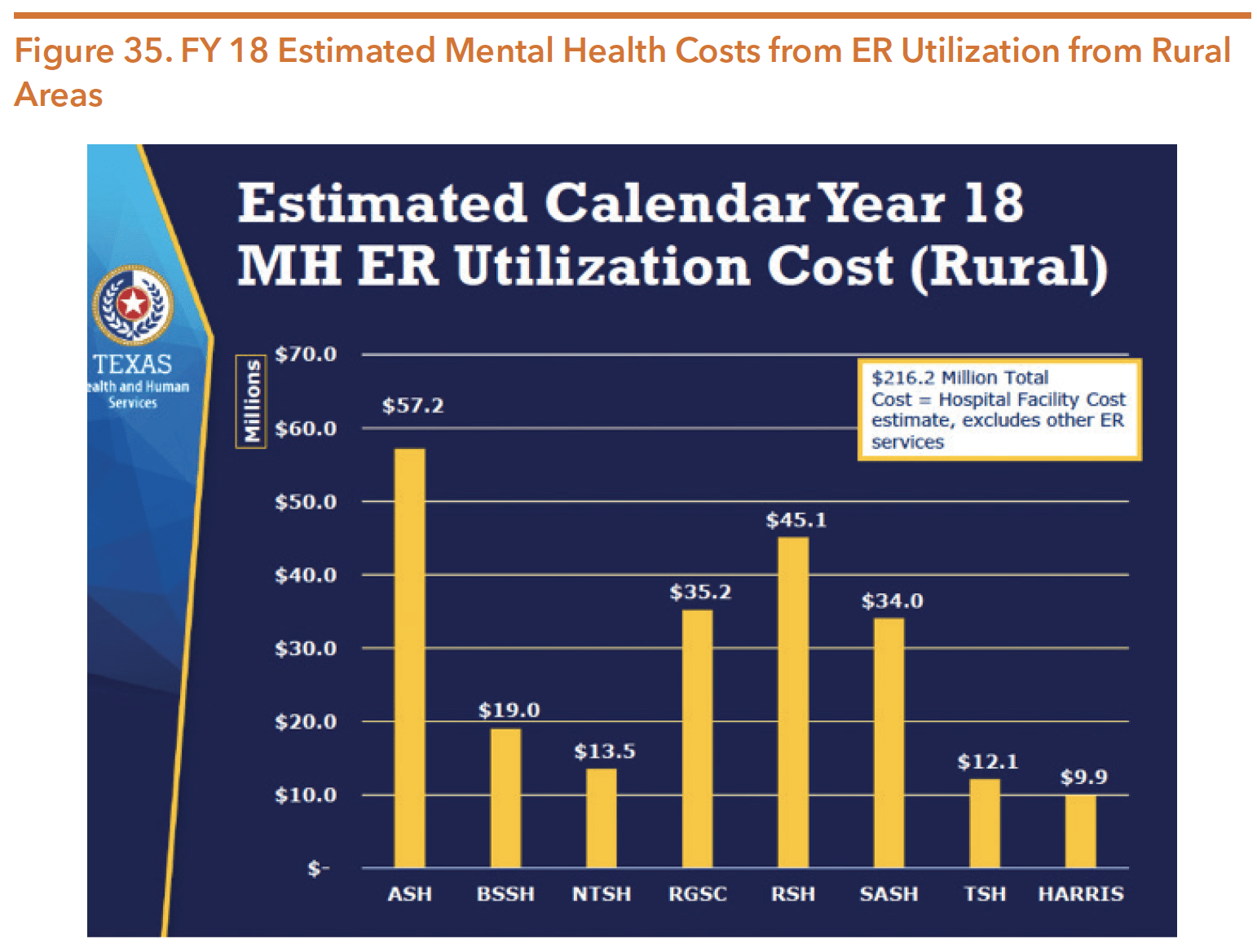

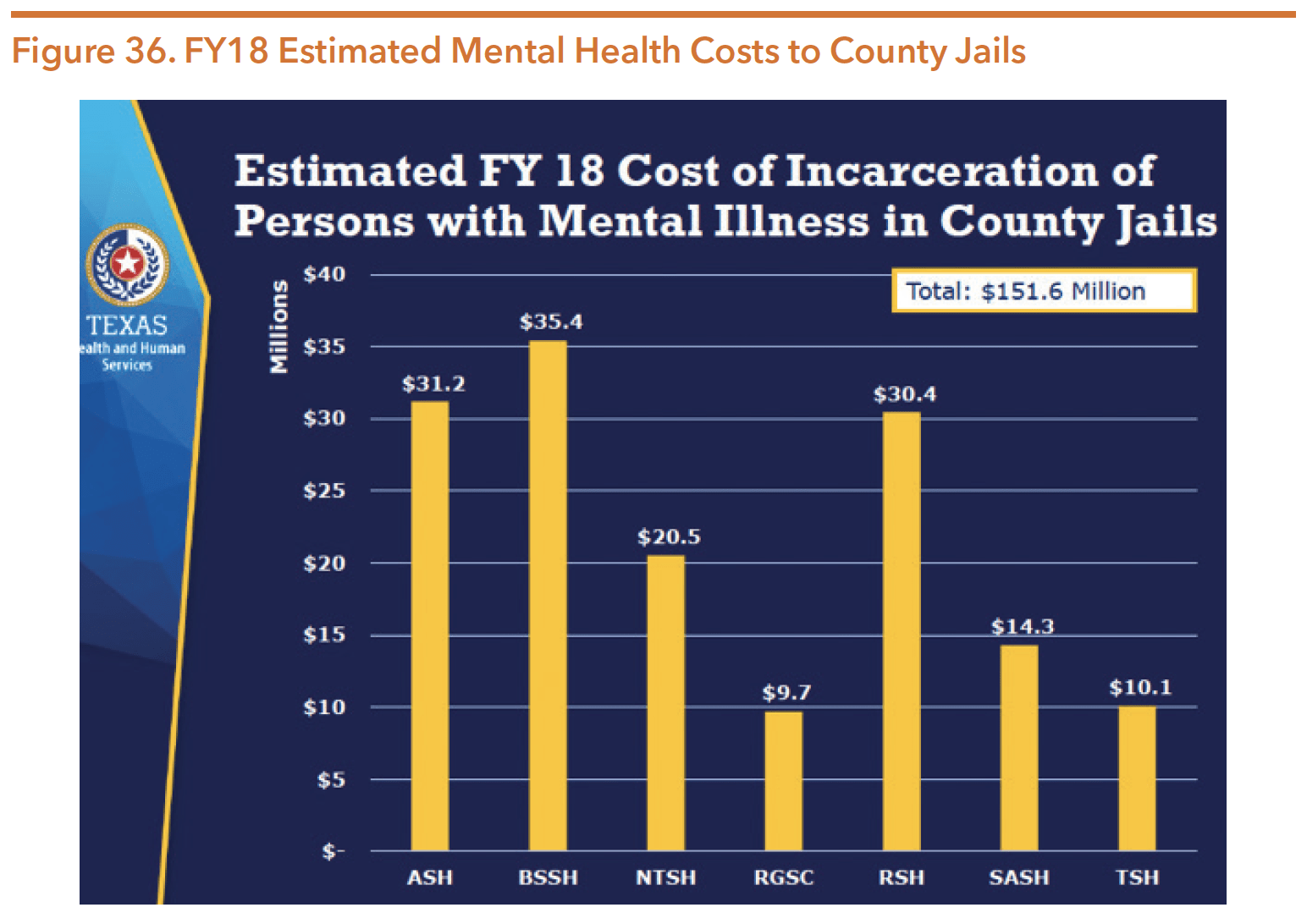

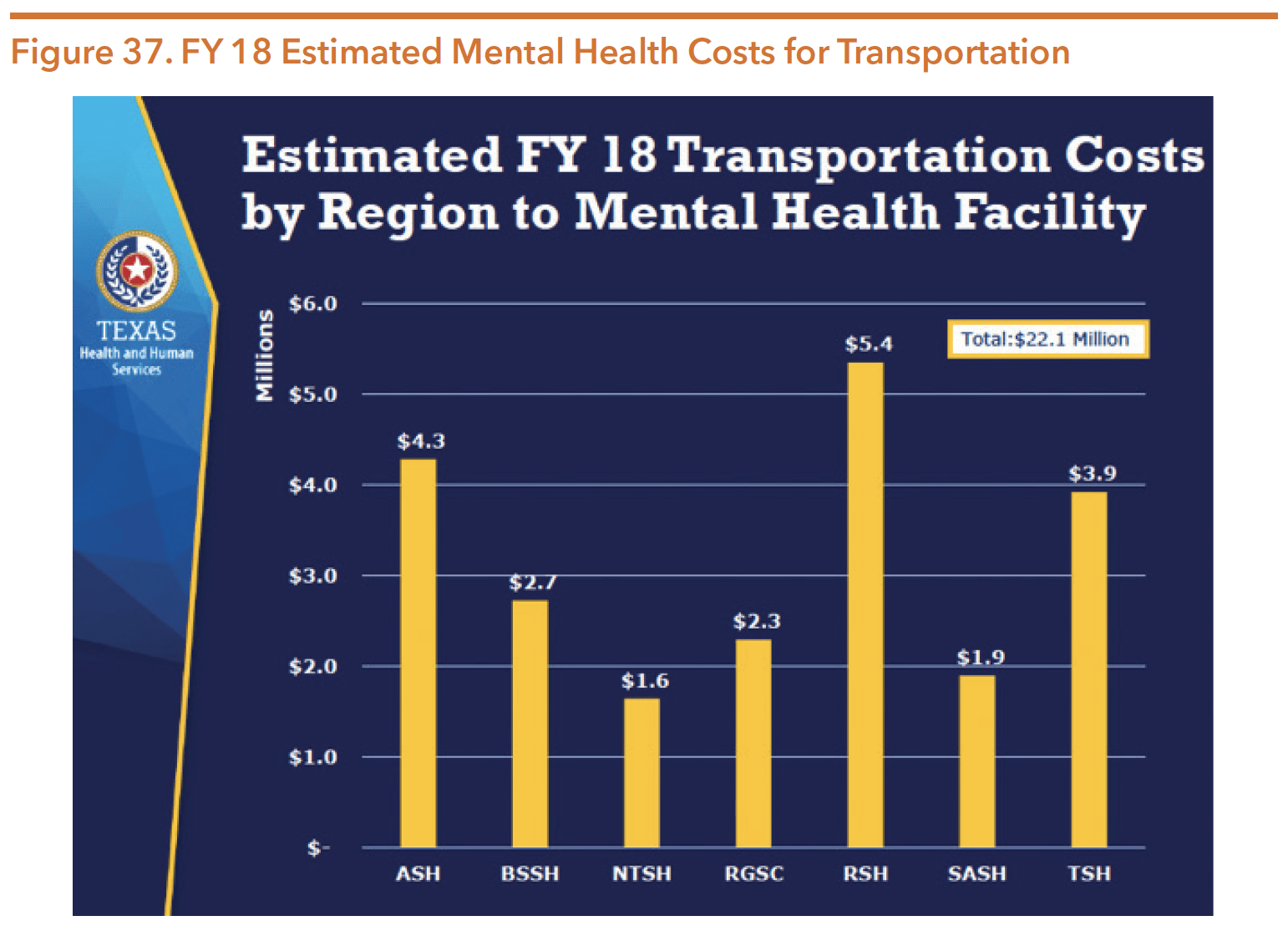

SB 633 directs HHSC to create regional authority groups of local mental health authorities serving populations of less than 250,000 in order to increase access to mental health services. HHSC is required to develop a mental health services development plan for each local mental health authority group that will increase the capacity in the group to provide access to needed services. The plans are required to focus on reducing the costs of mental health crisis services, transportation costs for those served by the local authorities to mental health facilities, incarceration of individuals with mental illnesses in county jails, and hospital emergency room visits for individuals with mental illnesses.

SB 670 (BUCKINGHAM/PRICE) TELEHEALTH INITIATIVES

SB 670 requires HHSC to encourage health care providers and health care facilities to provide telemedicine medical services and telehealth services, including mental health and substance use services. Requires HHSC to implement a number of changes to ensure that Medicaid managed care organizations reimburse for telemedicine and telehealth services at the same rate as in-person services.

SB 750 (KOLKORST/BUTTON) HEALTHY TEXAS WOMEN’S PROGRAM

SB 750 contains many provisions aimed at improving health care services for women in both the state Medicaid program and the Healthy Texas Women Program, including:

- Prenatal care and postpartum care;

- Both physical health care and behavioral health care services including requiring HHSC to develop statewide initiatives to improve the quality of maternal health care services and outcomes for women in Texas;

- A study to assess the feasibility of providing Healthy Texas Women Program services through managed care; and

- Mental health and substance use services, including provisions for HHSC:

- To apply for federal funding to implement a model of care that improves the quality and accessibility of care for pregnant women with opioid use conditions during the prenatal and postpartum periods, and their children after birth; and

- To develop and implement a postpartum depression treatment network for women enrolled in either program in collaboration with Medicaid managed care organizations.

SB 1177 (KOLKHORST/ROSE) “INLIEUOF” MEDICAID BILL

SB 1177 instructs HHSC to update Medicaid managed care contracts to include language permitting an MCO to offer medically appropriate, cost-effective, and evidence-based services from a list approved by the state Medicaid managed care advisory committee “in lieu of” mental health or substance use conditions services specified in the state Medicaid plan.

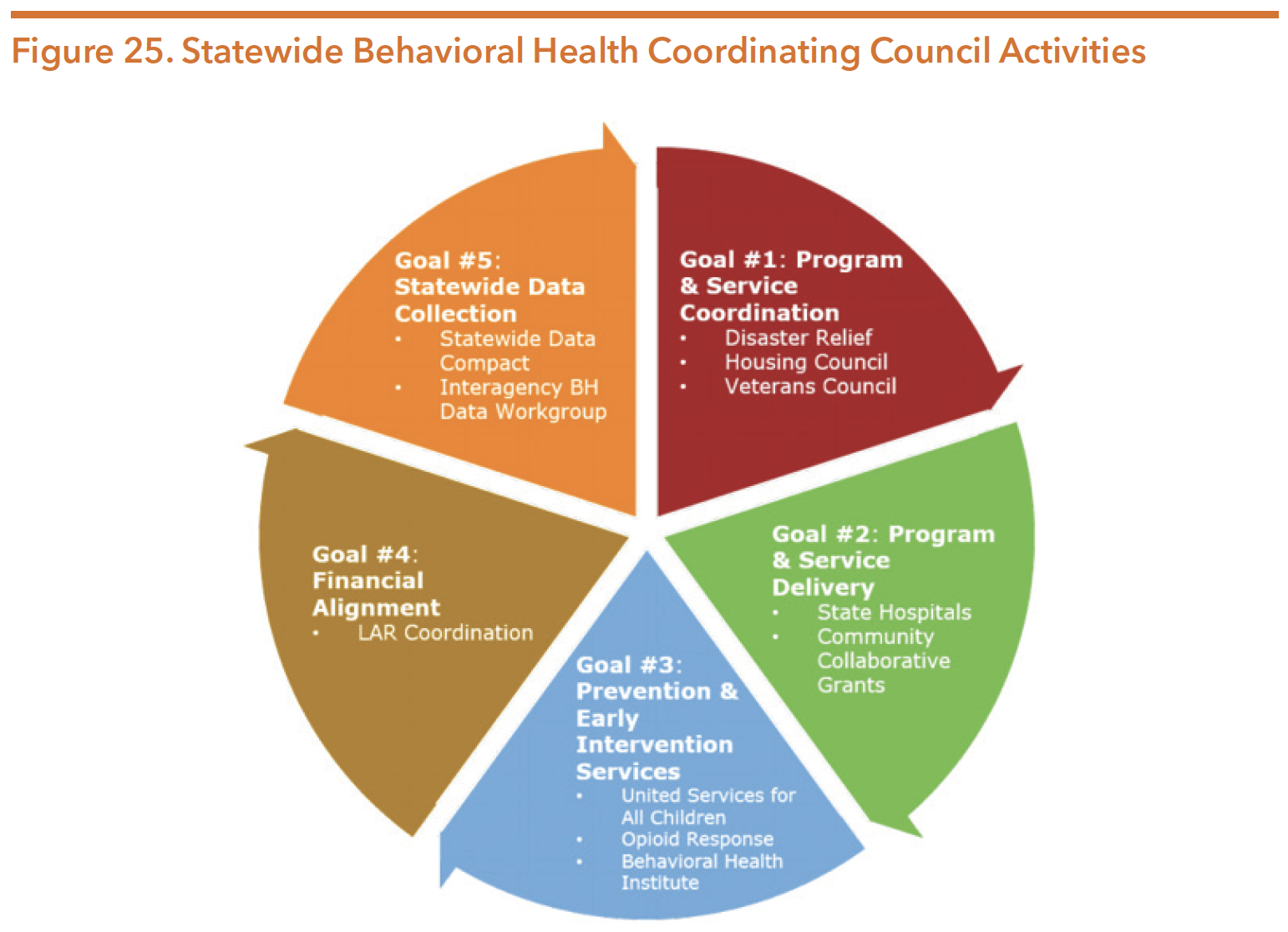

HB 2813 (PRICE/NELSON) STATEWIDE BEHAVIORAL HEALTH COORDINATING COUNCIL

HB 2813 establishes the statewide behavioral health coordinating council for a strategic statewide approach to behavioral health services. The bill codifies the council’s requirement to develop and monitor the implementation of a five-year behavioral health strategic plan, develop a biennial expenditure report, and publish an inventory of state-funded services and programs.

HB 3980 (HUNTER/MENENDEZ) SUICIDE PREVENTION EFFORTS ACROSS STATE SYSTEMS

HB 3980 directs HHSC and DSHS to publish a report on the prevalence of suicide in Texas and prevention efforts across state systems and agencies, including:

- Available state and regional data of the prevalence of suicide-related events, including thoughts, attempts, and deaths caused by suicide. Data is disaggregated by county and is longitudinal as able;

- Identification of the highest categories of risk with correlational data;

- State statutes, agency rules, and policies related to suicide prevention, intervention, and postvention; and

- Agency initiatives since 2000 addressing suicide, including funding sources and years of operations.

Additionally, HB 3908 directs the Statewide Behavioral Health Coordinating Council to establish a stakeholder workgroup to assist in preparing a legislative report. The report is required to identify opportunities and make recommendations to improve statewide data collection related to suicide, to use data to guide and inform decisions and policy development, and to decrease suicides while targeting the highest risk categories.

HB 3285 (SHEFFIELD/HUFFMAN) OMNIBUS SUBSTANCE USE BILL

HB 3285 is a comprehensive bill addressing substance use across a number of agencies. While the bill addresses various initiatives, the following are brief descriptions of a few changes requiring HHSC or DSHS involvement. This is not a complete summary of the provisions of the bill:

- Requires the executive commissioner of HHSC to establish a program that increases opportunities and expands access to telehealth treatment for substance use across Texas;

- Requires the Statewide Behavioral Health Strategic Plan to include a subplan for substance use issues;

- Requires DSHS to create an opioid misuse public awareness campaign;

- Requires the executive commissioner of DSHS to ensure the data collection of opioid overdose deaths, co-occurrence of substance use and mental illness, and evaluation of the current treatment capacity for individuals with co-occurring substance use and mental health concerns; and

- Requires Medicaid reimbursement for medication-assisted treatment (MAT) without prior authorization or pre-certification, with the exception of methadone.

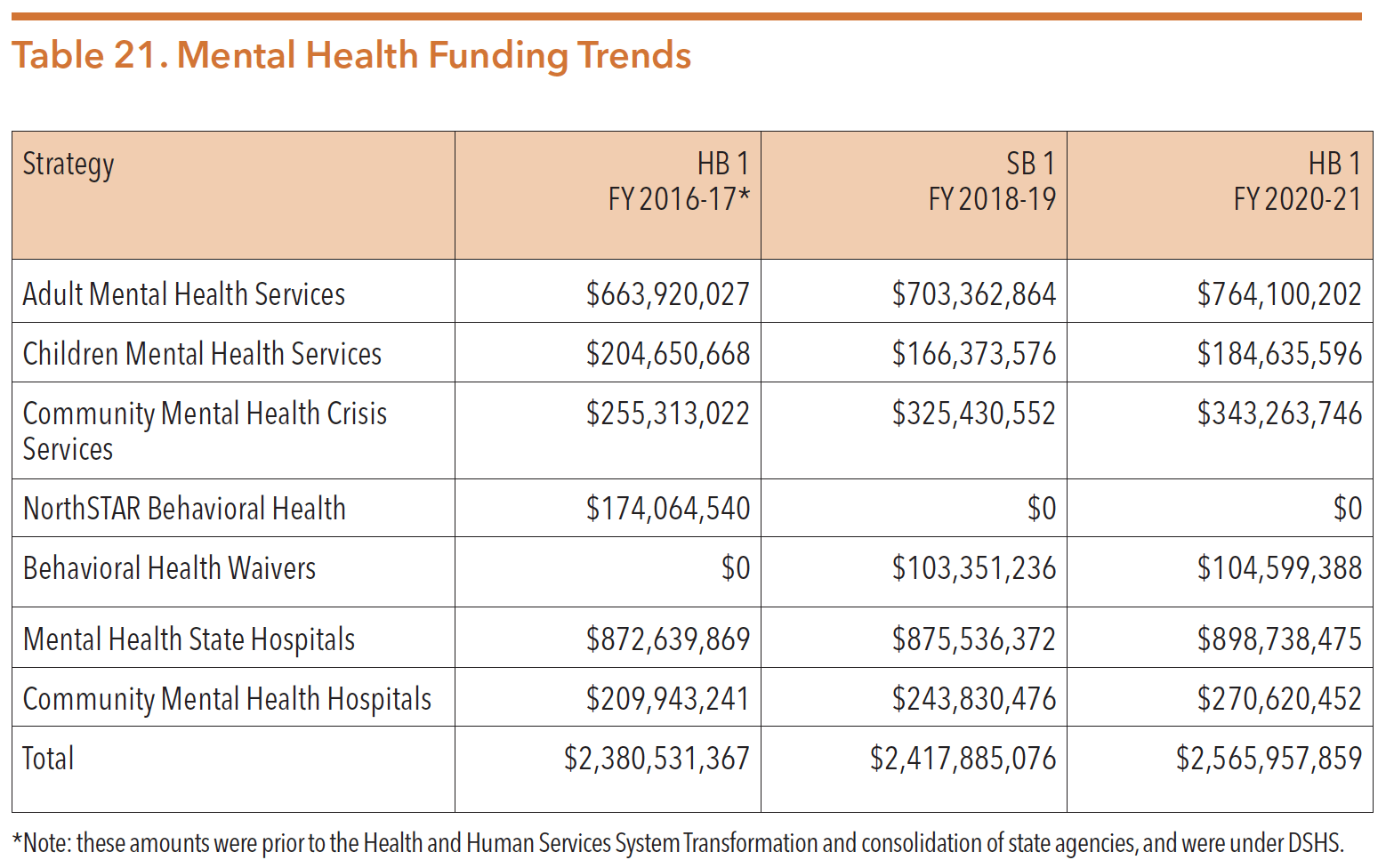

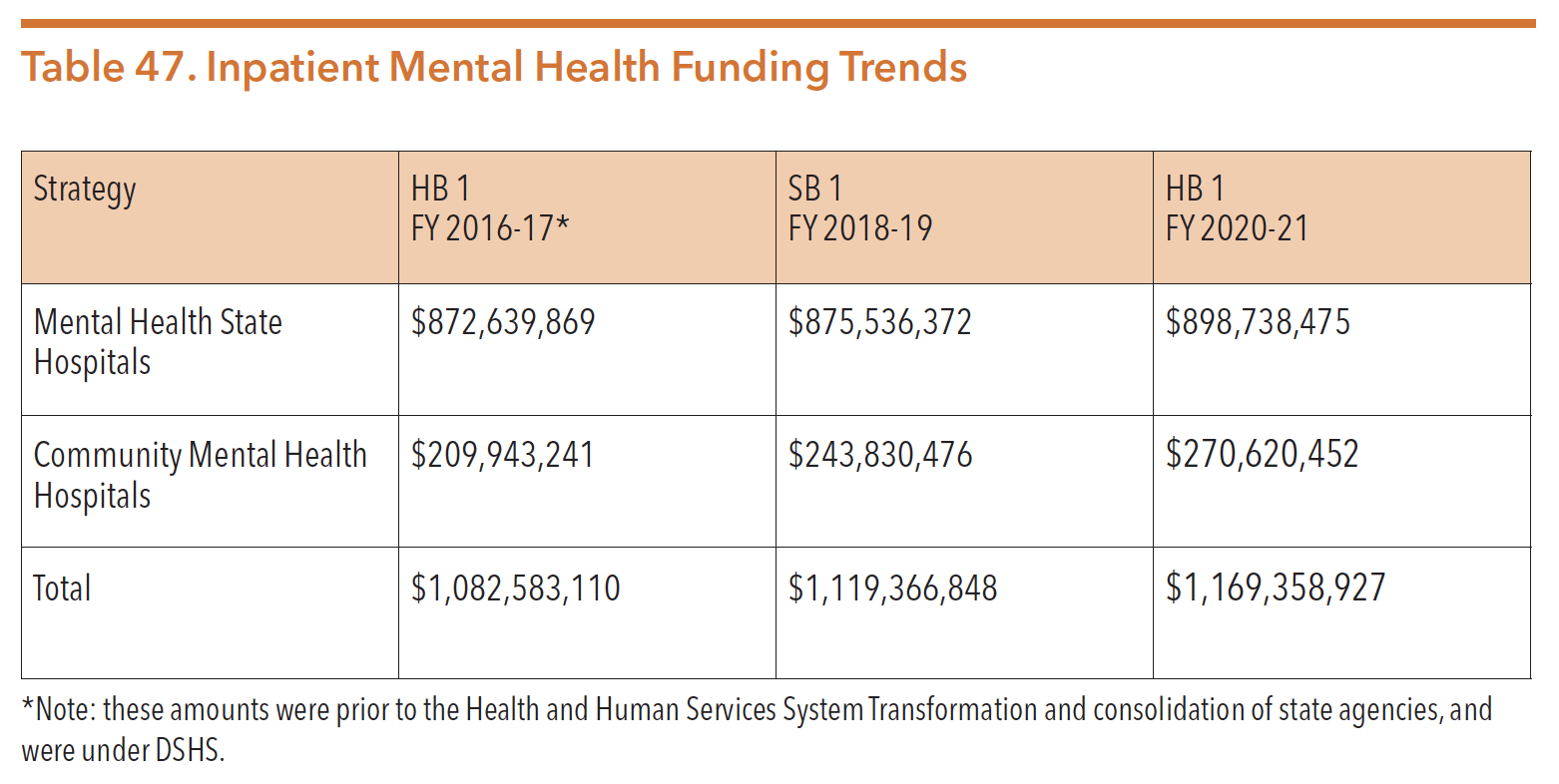

Funding

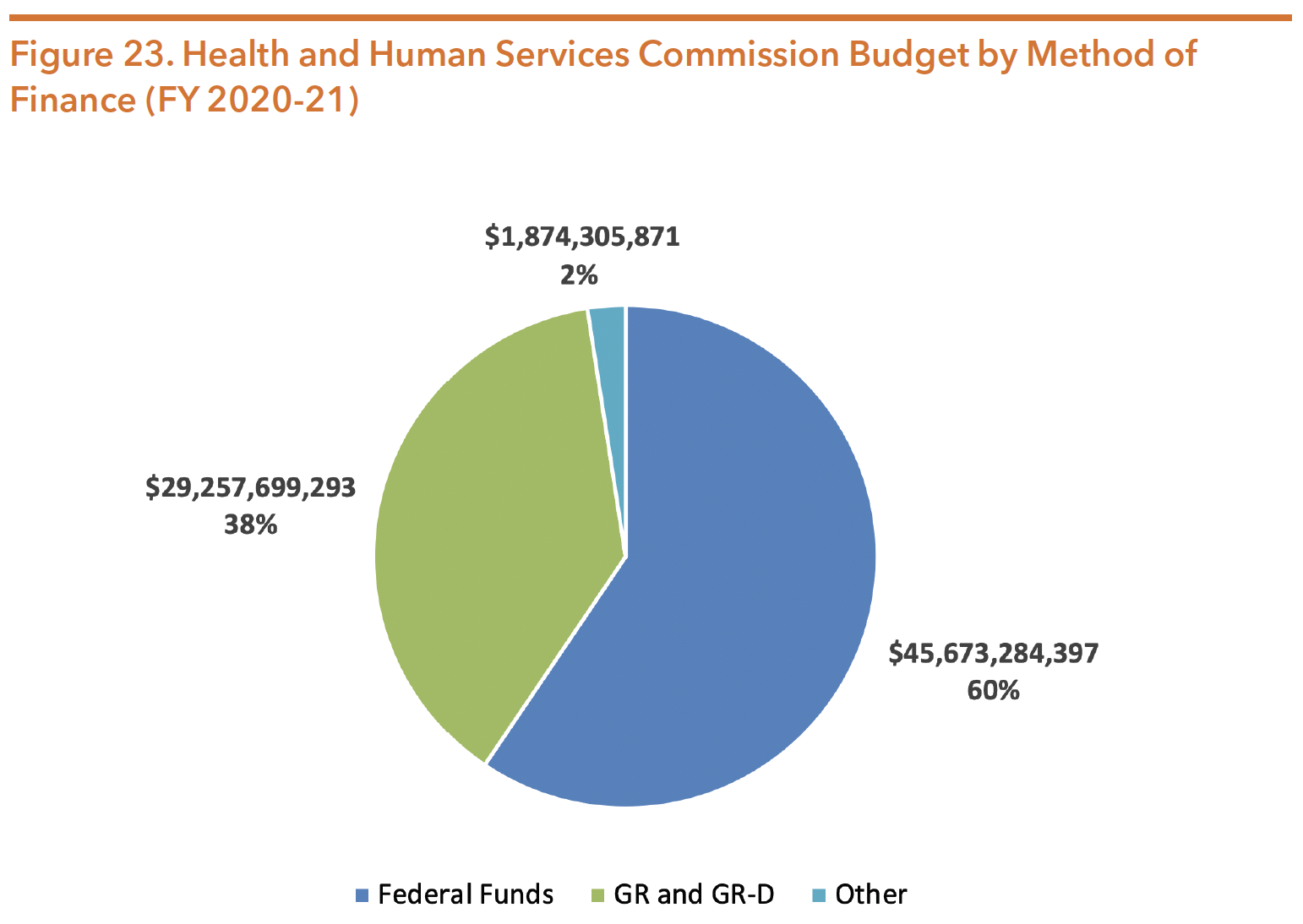

HHSC funding continues to be a major component of the State of Texas biennial budget comprising approximately 30 percent of the total budget for the FY 2020- 21 biennium.27 Mental health and substance use funding has historically been underfunded, including reimbursement rates for providers. This impacts provider willingness to participate in the state Medicaid program which in turn directly impacts access to services. The Texas Legislature has increased mental health funding over the last several biennia, but many programs and services remain underfunded. In the most recent budget, Texas increased substance use funding, however was only a small fraction of HHSC’s request, and was the first increase in the last decade.

Source: Texas Legislature Online (2019). H.B.1, General Appropriations Act, 86th Legislature, FY 2020-21. Retrieved from https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/86R/billtext/pdf/HB00001F.pdf#navpanes=0

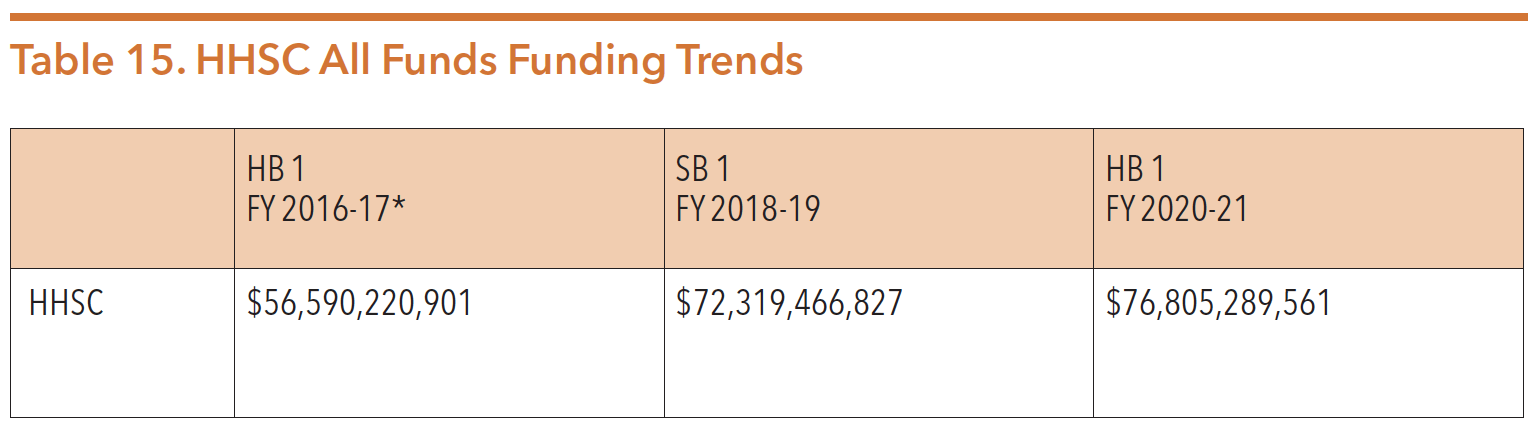

Table 15 below shows the HHSC All Funds funding trends over the last three budget cycles.

*Note: this amount was prior to the Health and Human Services System Transformation and consolidation of state agencies

Sources: Texas Legislature Online (2019). H.B.1, General Appropriations Act, 86th Legislature, FY 2020-21. Retrieved from https:// capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/86R/billtext/pdf/HB00001F.pdf#navpanes=0

Texas Legislature Online (2017). S.B.1, General Appropriations Act, 85th Legislature, FY 2018-19. Retrieved from https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/85R/billtext/pdf/SB00001F.pdf#navpanes=0

Texas Legislature Online (2015). H.B.1, General Appropriations Act, 84th Legislature, FY 2016-17. Retrieved from https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/84R/billtext/pdf/HB00001F.pdf#navpanes=0

HHSC Advisory Committees

After the Sunset Commission reviewed all Health and Human Services advisory committees, the continuing committees were re-established in rule; a list is available on the HHSC website at https://hhs.texas.gov/about-hhs/leadership/ advisory-committees.

Several of the continuing committees have a direct impact on mental health and substance use policies, including but not limited to:

- Behavioral Health Advisory Committee

- Drug Utilization Review Board

- E-Health Advisory Committee

- Early Childhood Intervention Advisory Committee

- Medical Care Advisory Committee

- Policy Council for Children and Families Committee

- STAR Kids Managed Care Advisory Committee

- State Medicaid Managed Care Advisory Committee

- Texas Autism Council

- Texas Council on Consumer Direction

- Texas School Health Advisory Committee

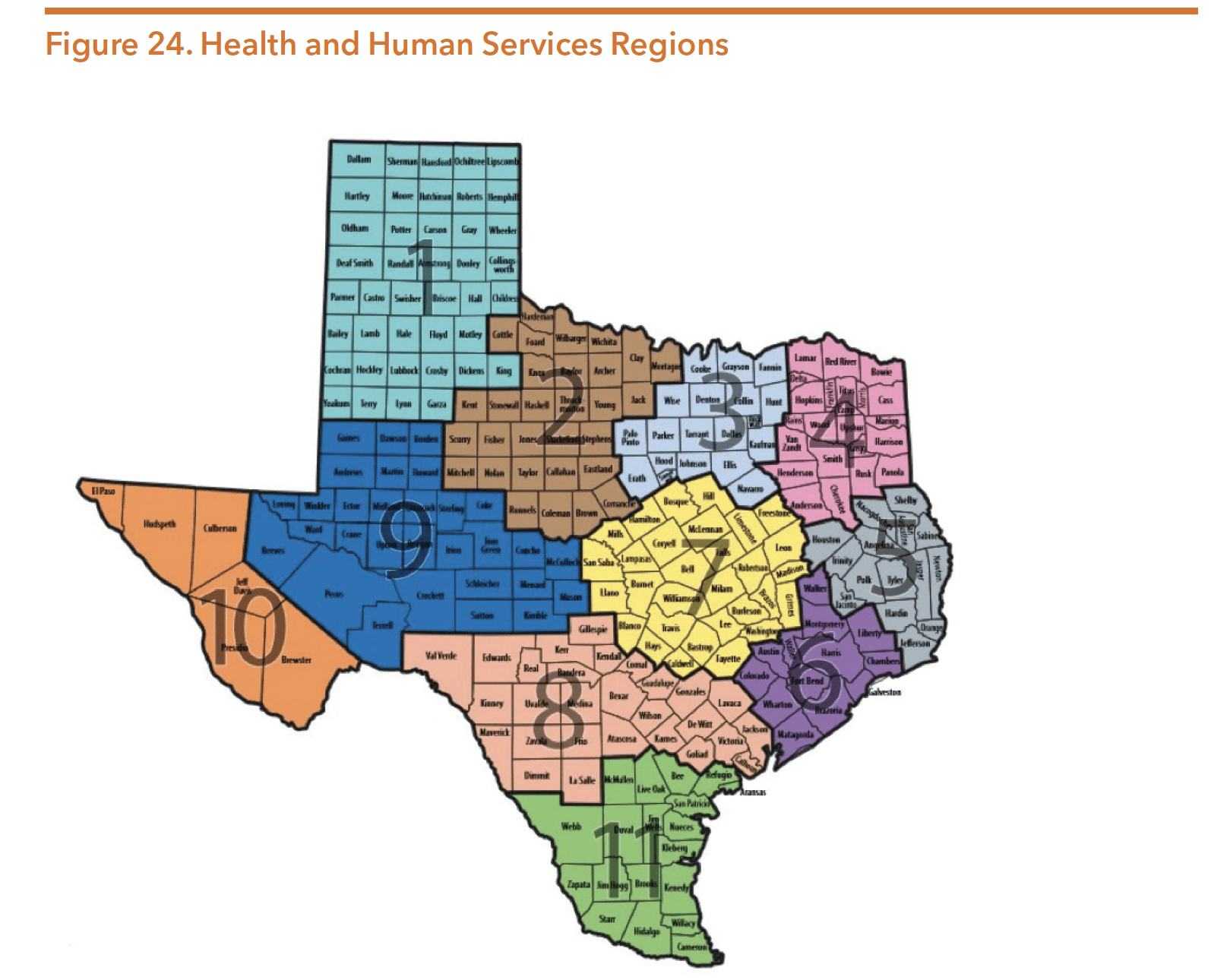

HHS Regions

For service delivery administration, the state is divided into 11 HHS regions, displayed in Figure 24. As of August 2019, the HHS system employed over 36,346 full-time employees.

Source: Texas Health and Human Services Commission. (2016). Health and Human Services offices by county. Retrieved from https://hhs.texas.gov/sites/default/files/documents/about-hhs/hhs-regional-map.pdf

Medical and Social Services Division

The Medical and Social Services Division is responsible for:

- Medicaid and CHIP Services

- IDD and Behavioral Health Services Division

- Health, Developmental & Independence Services Division

- Access and Eligibility Services

OFFICE OF MENTAL HEALTH COORDINATION

In recent years, mental health and substance use (often referred to as “behavioral health”) have become major topics of both state and national dialogue. The Texas Legislature took steps to increase and improve cross-agency planning, coordination, and collaboration in effort to be more strategic with behavioral health service delivery and funding. In 2013, the legislature created the Office of Mental Health Coordination tasked with providing broad oversight for state mental health policy as well as managing cross-agency coordination of behavioral health programs, services, and expenditures. The office reports directly to the deputy executive commissioner for IDD & Behavioral Health Services. The office developed a website to provide consumers, families, and providers with up-to-date information on mental health and substance use programs and services. More information is available at http:// www.mentalhealthtx.org.

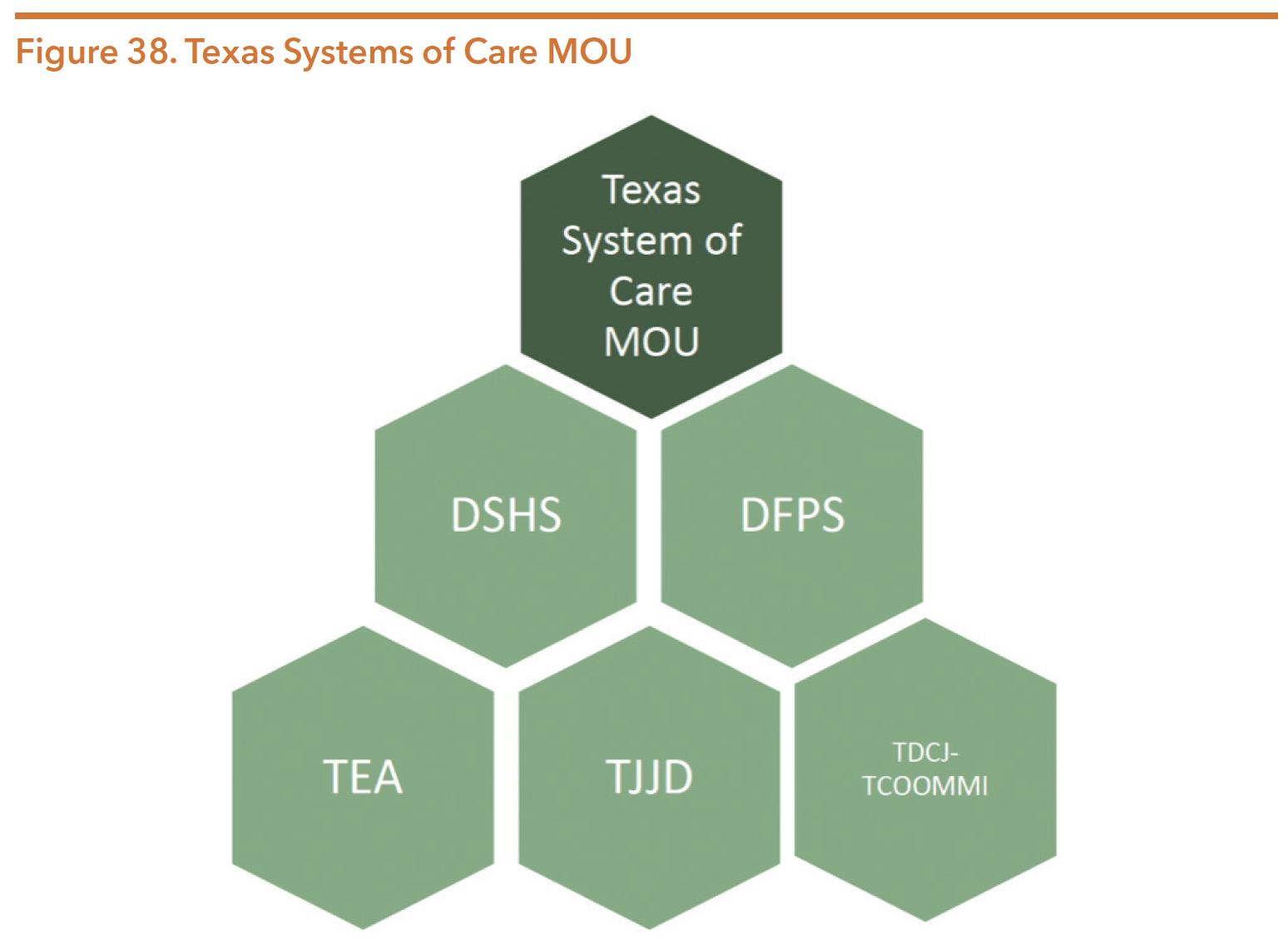

STATEWIDE BEHAVIORAL HEALTH COORDINATING COUNCIL

In 2015, the legislature established the Statewide Behavioral Health Coordinating Council (SBHCC). The HHSC assistant commissioner, who oversees the Office of Mental Health Coordination at HHSC, serves as chair of the council.30 Agencies and departments work together under the direction of the Office of Mental Health Coordination to ensure a strategic statewide approach to behavioral health services. During the 86th legislative session, Texas lawmakers passed House Bill 2813 (Price/ Nelson), codifying the SBHCC. While other state agencies or institutions may be authorized to serve on the SBHCC, the agencies required to be represented are:

- Texas Health & Human Services Commission

- Office of the Texas Governor

- Texas Veterans Commission

- Texas Department of State Health Services

- Texas Department of Family and Protective Services

- Texas Civil Commitment Office

- University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston

- University of Texas Health Science Center at Tyler

- Texas Department of Criminal Justice

- Texas Correctional Office on Offenders with Medical or Mental Impairments

- Texas Juvenile Justice Department

- Texas Military Department

- Texas Health Professions Council (includes six member agencies)

- Texas Education Agency

- Texas Tech University System

- Texas Commission on Jail Standards

- Texas Workforce Commission

- Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs

- Texas Indigent Defense Commission

- Texas Court of Criminal Appeals

The SBHCC is responsible for developing and implementing the five-year Statewide Behavioral Health Strategic Plan, a biennial Coordinated Statewide Expenditure Proposal, and publishing an annual inventory of behavioral health programs funded by the state. The Coordinating Council also has a number of goals, and coordinating agencies collaborate on a number of activities shown in Figure 25.

Source: Texas Health and Human Services Commission. (March 2018). Presentation to the Senate Finance Committee: Statewide Behavioral Health Coordinating Council. Retrieved from https://hhs.texas.gov/sites/default/files/documents/laws-regulations/reports-presentations/2018/leg-presentations/senate-finance-hearing-march-20-2018.pdf

THE STATEWIDE BEHAVIORAL HEALTH STRATEGIC PLAN

The Statewide Behavioral Health Strategic Plan identifies 15 primary gaps in behavioral health services in Texas. The plan’s framework and goals are intended to address gaps and challenges within the behavioral healthcare system, as well as improve access to care and outcomes. The second edition of the plan is available at https://hhs.texas.gov/sites/default/files/documents/laws-regulations/reports-presentations/2019/hb1-statewide-behv-hlth-idd-plan-feb-2019.pdf

The most recent progress report as of September 2020 was printed in December 2019 and is available at https://hhs.texas.gov/reports/2019/12/ texas-statewide-behavioral-health-strategic-plan-progress-report-fiscal-year-2019

Chairwoman Jane Nelson has indicated that any legislative proposals directed toward behavioral health should address one or more of these identified gaps. The gaps include:

- Access to appropriate behavioral health services

- Behavioral health needs of public school students

- Coordination across state agencies

- Veteran and military service members supports

- Continuity of care for individuals exiting county and local jails

- Access to timely treatment services

- Implementation of evidence-based practices

- Use of peer services

- Behavioral health services for individuals with intellectual disabilities

- Consumer transportation and access to treatment

- Prevention and early intervention services

- Access to housing

- Behavioral health workforce shortage

- Services for special populations

- Shared and usable data

As a result of the passage of HB 3285 (Sheffield/Huffman), SBHCC is required to create a subplan specifically addressing substance use, including:

- Addressing challenges of existing prevention, intervention, and treatment programs;

- Evaluation of substance use conditions prevalence;

- Identifying substance use treatment services availability and gaps; and

- Collaborating with state agencies to expand substance use treatment service capacity in the state

According to HHSC, as of August 2020, the agency has organized an internal workgroup with plans to engage stakeholders moving forward. The development of the substance use subplan will be developed in tandem with the full Statewide Behavioral Health Strategic Plan to be due December 2021.

THE COORDINATED STATEWIDE BEHAVIORAL HEALTH EXPENDITURE PROPOSAL

The SBHCC develops the Coordinated Statewide Behavioral Health Expenditure Proposal. The proposal identifies the total behavioral health funding proposed by each agency for the upcoming fiscal year. Expenditures are linked to various strategies in the strategic plan to demonstrate how state appropriations will be used to further its goals during the fiscal year. The full proposal is available at https://hhs.texas.gov/sites/default/files/documents/laws-regulations/reports-presentations/2019/hb1-behavioral-health-expenditure-proposal-fy20.pdf

HHSC compiles a consolidated report of behavioral health funding across agencies, a summary of which can be found in the funding section of this guide.

VETERAN SERVICES DIVISION

The Veteran Services Division within HHSC was created in 2013 to coordinate, strengthen, and enhance veteran services across state agencies. The division’s focus is to review and analyze current programs, engage the charitable and nonprofit communities, and create public-private partnerships to benefit these programs. The Veterans Services Division is an active participant in the Texas Coordinating Council for Veterans Services. The HHS Enterprise offers Texas veterans services through several agencies including but not limited to the Department of State Health Services, Texas Veterans Commission (TVC), and Texas Workforce Commission. More information on veterans can be found in the TVC section of this guide.

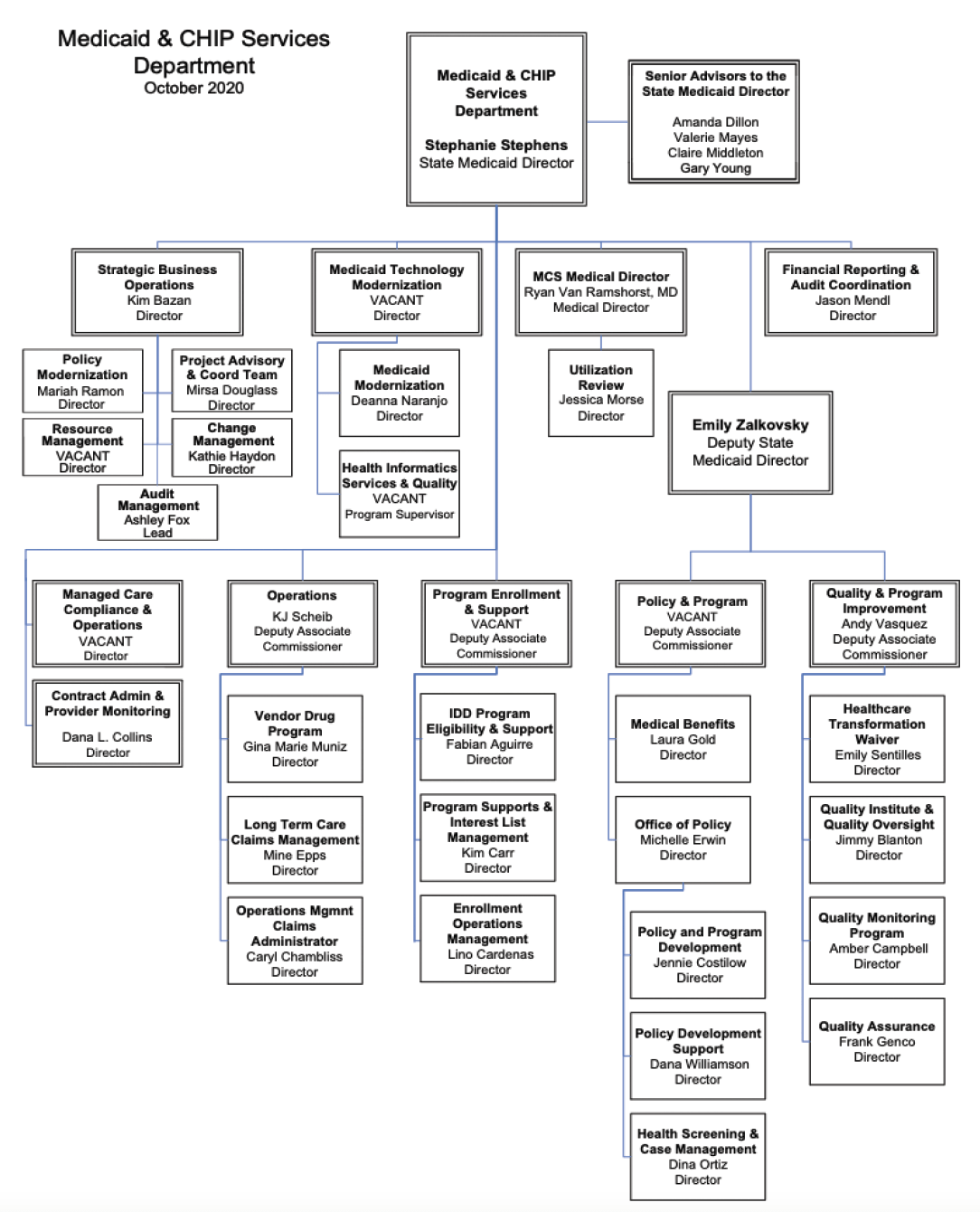

Medicaid & CHIP Service

Source: Texas Health and Human Services Commission. (October 2020). Public Information Request, October 2020.

MEDICAID

Medicaid is a jointly funded federal and state health care program authorized in Title XIX of the Social Security Act. It was created to provide health care benefits primarily to children in low-income families, pregnant women, and people with disabilities. The Texas Medicaid Program was first established in Texas in 1967. In January 2020, total Texas Medicaid and CHIP enrollment was 3,870,036 with 3,176,504 child enrollees.

Medicaid is an entitlement program, meaning that anyone who meets the eligibility criteria has a right to receive needed services and cannot be placed on waiting lists. Medicaid primarily serves low-income individuals who meet certain financial and non-financial criteria to be eligible for services. Neither the federal government nor states can currently limit the number of eligible persons who enroll in the program.

The federal government defines the mandatory services that state Medicaid programs must provide and required eligible populations. States have the option to expand both the services offered and eligible populations through State Plan Amendments (SPAs), Medicaid waivers, and the Affordable Care Act (ACA). As of September 2020, 38 states and Washington, D.C. have adopted Medicaid expansion. Texas is one of 12 states that has chosen not to adopt this expansion. As federal requirements and state policies change over time, updates are made via SPAs. States can choose to submit SPAs to make changes to their programs; for example, to change a provider payment methodology or add coverage of an optional service. States can also make programmatic and eligibility changes by participating in Medicaid waiver programs to waive basic federal Medicaid requirements. Waivers can allow flexibility with mandated eligibility or required benefits in order to develop service delivery alternatives that improve cost efficiency or service quality. States can participate in three types of Medicaid waivers:

- Research and Demonstration 1115 Waivers give the state leniency to experiment with new service delivery models.

- Freedom of Choice 1915(b) Waivers allow the state to require clients to enroll in managed care plans and use the cost savings to enhance the Medicaid benefits package.

- Home and Community-based Services 1915(c) Waivers allow the state to provide community-based services to individuals who would otherwise be eligible for institutional care.

STATE MEDICAID AGENCY

HHSC has been the designated state Medicaid agency since 1993, administering the program and acting as a liaison between Texas and the federal government on related issues. The federal government establishes most Medicaid guidelines but grants several important tasks to the states, including:

- Administering the Medicaid State Plan, which functions as the contract between the agency and the federal government;

- Establishing Medicaid policies, rules, and provider reimbursement rates; and

- Establishing eligibility beyond the minimum federal eligibility groups

MEDICAID MANAGED CARE

Since the early 1990s, Texas has offered Medicaid coverage through two service models: fee-for-service (FFS) and managed care. In a traditional FFS model, providers receive payment for each individual service delivered. The FFS model is now limited to very few Medicaid participants, primarily those who are dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare. As of November 2019, approximately 94.4 percent of Medicaid services in Texas were provided through managed care. In a Medicaid managed care system, individuals access services through a Managed Care Organization (MCO), also known as a health plan. HHSC contracts with MCOs and pays them a monthly amount (capitated rate) per Medicaid enrollee to coordinate health services for each member enrolled in their health plan. All CHIP services are delivered through managed care.

MCOs are responsible for creating a network of public and private providers to ensure that adults and children receiving Medicaid can access needed services. MCOs are responsible for service authorization and reimbursement to service providers. With support from the Medicaid 1115 Transformation Waiver, Texas has incrementally expanded its Medicaid managed care system to include more services and populations.

In a managed care system, the Medicaid member selects a health plan and identifies a primary care physician from that plan’s provider network. Individuals have a choice between two or more health plans in each HHS service region. Members have the option to change plans if they are unsatisfied. In addition to contractual requirements and state monitoring, members’ ability to switch plans generates some level of competition between health plans that is intended to result in higher quality services.

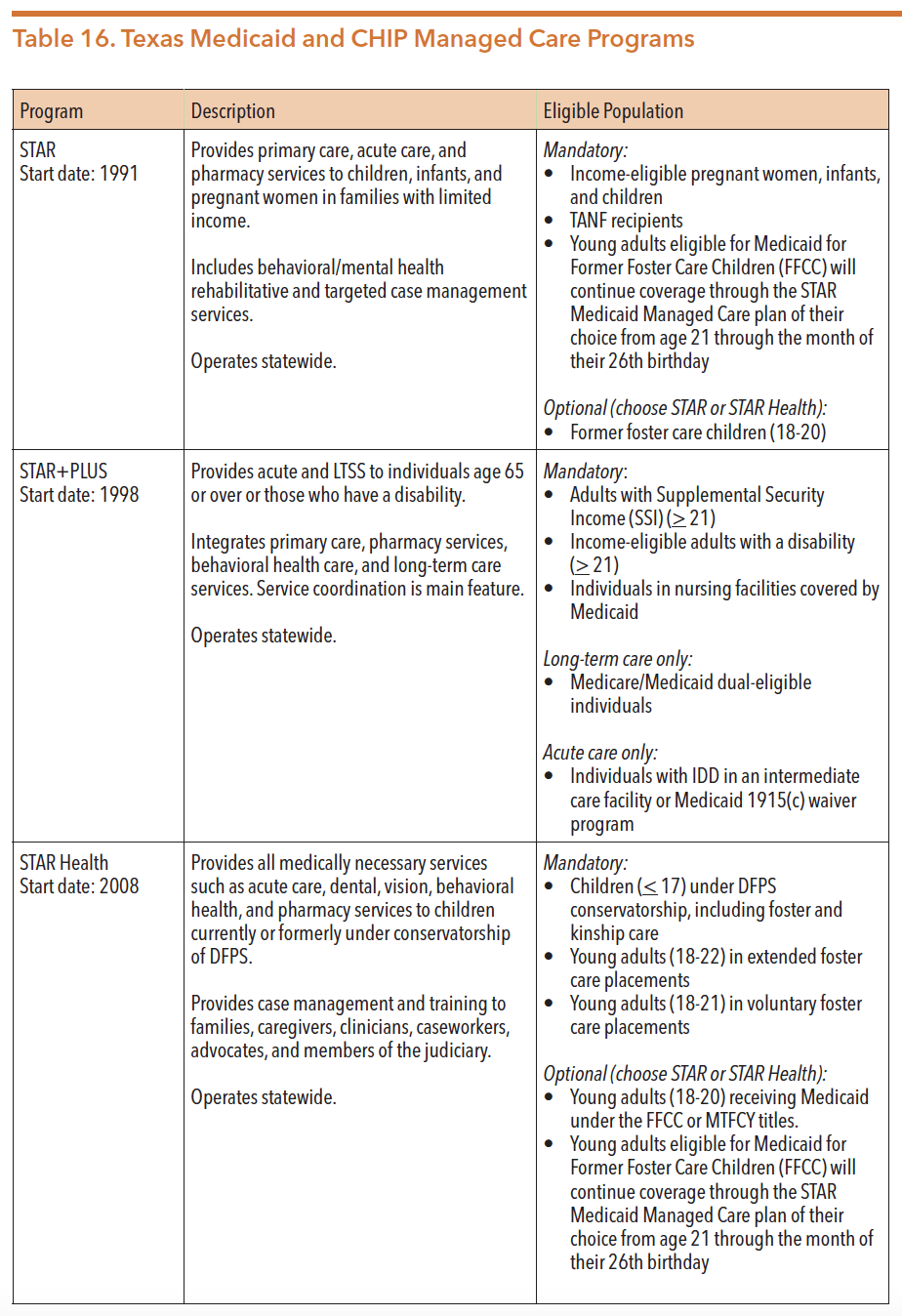

Managed care programs in Texas include:

- STAR: serves children, newborns, pregnant women, and some families and children;

- STAR+PLUS: serves individuals with a disability and who are older than 65 (including those with dual eligibility for Medicare), and women with breast or cervical cancer;

- STAR HEALTH: serves children who receive Medicaid through DFPS and former foster care youth;

- STAR Kids: serves children and young adults 20 years of age and younger with a disability; and

- CHIP: serves children in families who do not meet income requirements for Medicaid, but who are unable to afford private health insurance.

Recently, more Texas Medicaid clients have enrolled in managed care, an increase from 86 percent in 2016 to approximately 94 percent in July 2019. This is in large part due to the implementation of SB 7 (83rd, Nelson/Raymond), which expanded mandatory participation in the existing STAR+PLUS managed care program beginning in September 2013. STAR+PLUS is specifically for people who have disabilities or are age 65 or older. People in STAR+PLUS get Medicaid healthcare and long-term services and support.

Senate Bill 7 directed the design and implementation of a comprehensive system of acute care and long-term services and supports for adults and children, including those with disabilities. The bill generated immediate system delivery changes in Medicaid by expanding STAR+PLUS to serve all areas of the state, as well as transitioning nursing facility services and acute care services for individuals with IDD into STAR+PLUS.

Many of the changes instituted by SB 7 address coverage for individuals with IDD, who are three times more likely to experience a mental health condition than the general population. To advise HHSC through the system redesign of transitioning long-term services and supports (LTSS) to Medicaid managed care, the IDD System Redesign Advisory Committee was created. More information on the advisory committee can be found at https://hhs.texas.gov/about-hhs/leadership/advisory-committees/ intellectual-developmental-disability-system-redesign-advisory-committee.

Between 2014 and 2016, HHSC completed the transition of acute services from Medicaid FFS to STAR+PLUS, STAR Kids, and STAR Health managed care programs for all eligible recipients of Medicaid IDD waiver programs and intermediate care facilities (ICFs) for individuals with IDD. STAR Kids provides Medicaid managed care to children and adults 20 and younger who have disabilities, while STAR Health provides services for children and youth in the foster care system, including youth up to age 26 who have aged out of care.

In early 2019, HHSC completed and published evaluations to inform managed care on the transition of LTSS to managed care for individuals with IDD. Prior to the 86th legislative session, SB 7 required these services to be provided through managed care by 2020-21. However, HB 4533 (Klick/Kolkhorst) passed, extending the transition timeframe for TxHmL to 2027, CLASS to 2029, and HCS and DBMD to 2031. Additionally, HB 4533 requires HHSC to establish a pilot program prior to the transition, as well as establishes a Pilot Program Workgroup to provide assistance in developing and advising HHSC on the operation of the pilot program.

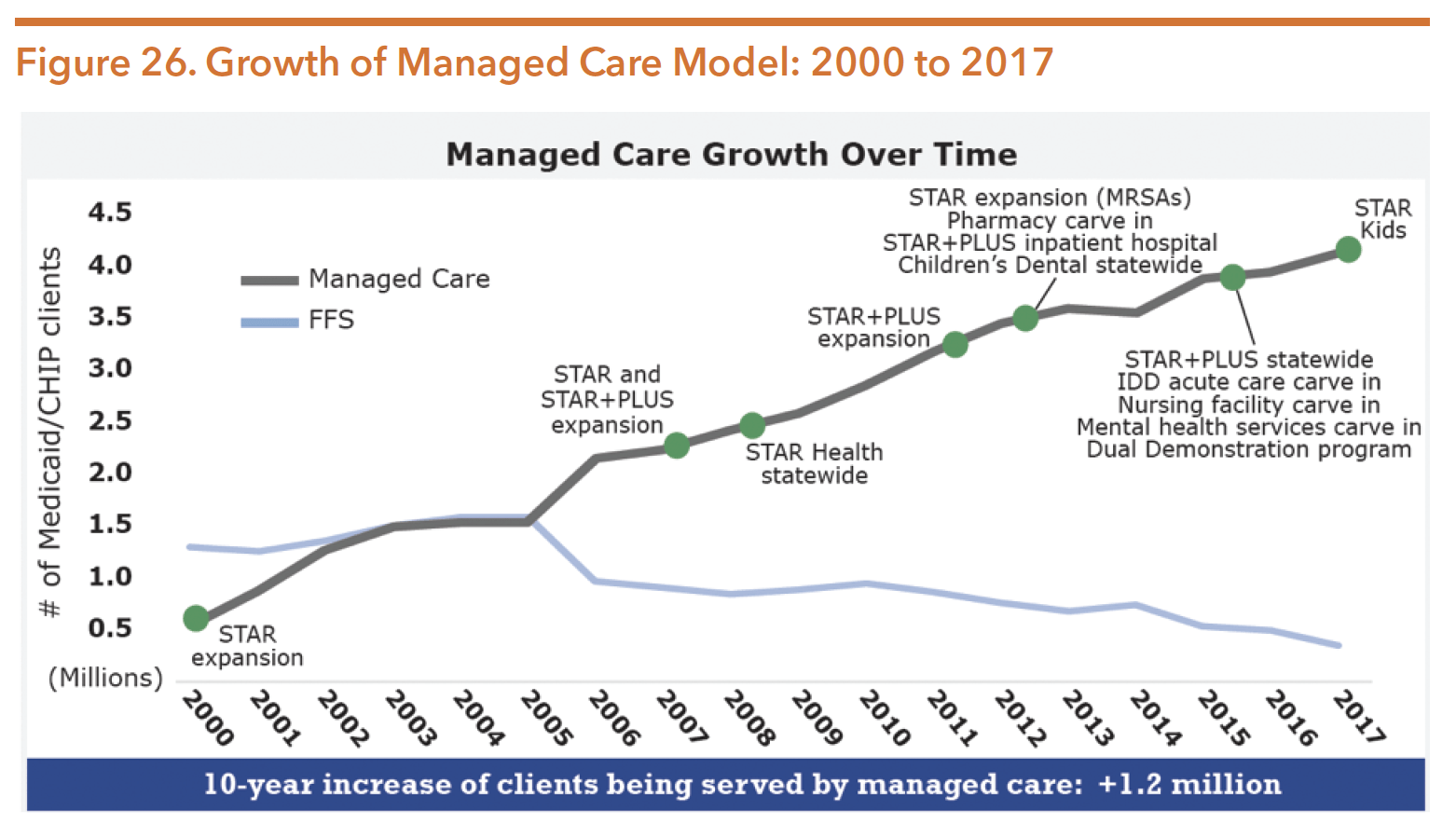

In addition to expanding care in STAR+PLUS, SB 7 established a new managed care program for children with disabilities called STAR Kids which launched in November 2016. Figure 26 depicts the growth of Medicaid managed care in Texas from 2000 through 2017.

Source: Texas Health and Human Services Commission. (2018). Texas Medicaid and CHIP in perspective twelfth edition. Retrieved from https://hhs.texas.gov/sites/default/files/documents/laws-regulations/reports-presentations/2018/ medicaid-chip-perspective-12th-edition/12th-edition-complete.pdf

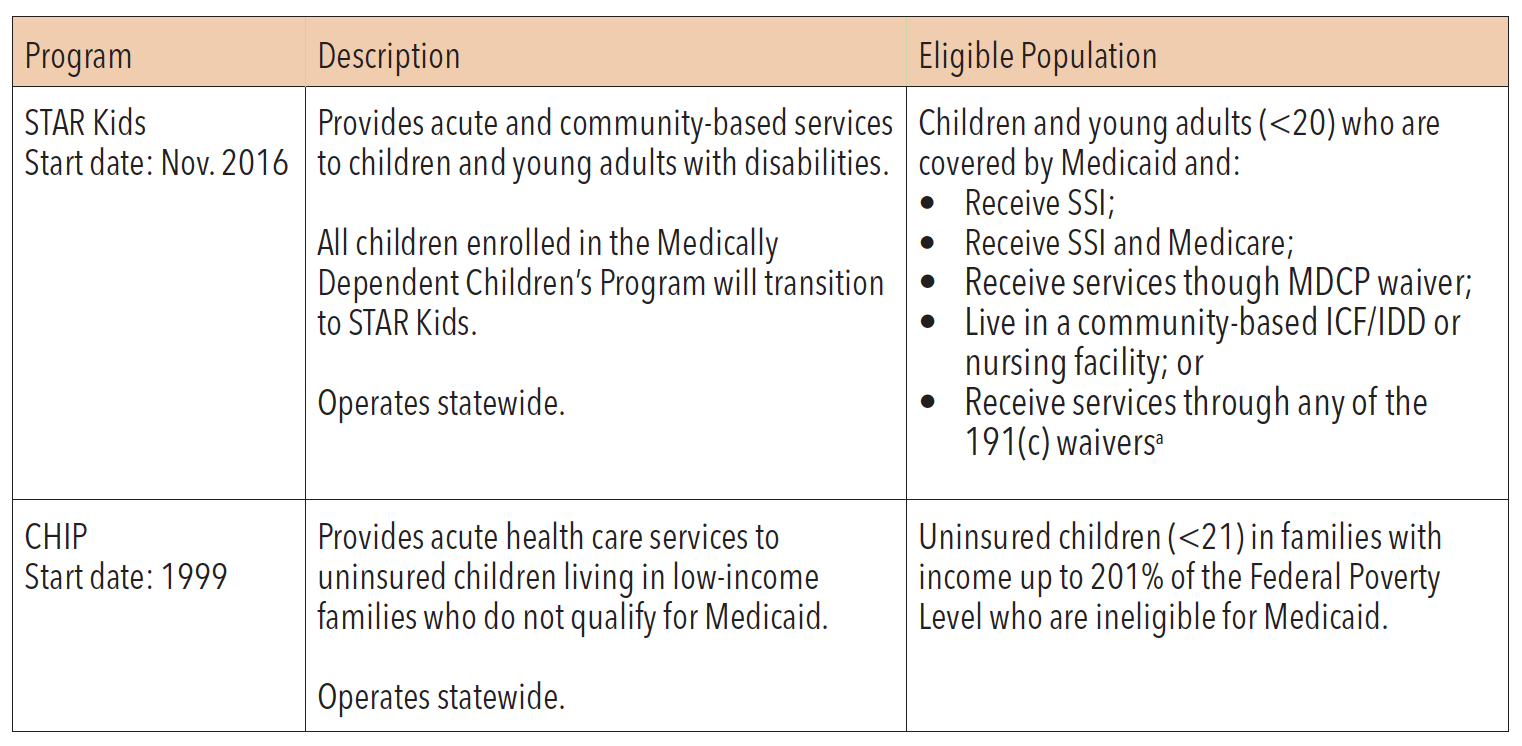

Table 16 describes the four Texas Medicaid and the CHIP managed care programs.

*Medicaid 1915(c) waiver programs for adults and children include Home and Community-based Services (HCS), Community Living Assistance & Support Services (CLASS), Texas Home Living (TxHmL), and Deaf Blind with Multiple Disabilities (DBMD). Youth Empowerment Services (YES) serves children and youth.

Sources: Institute for Child Health Policy at the University of Florida. (2016). Texas Medicaid managed care and Children’s Health Insurance Program, summary of activity and trends in healthcare quality, Contract Year 2016. Retrieved from https://hhs.texas. gov/sites/default/files/documents/about-hhs/process-improvement/quality-efficiency-improvement/ External-Quality-Review/tx-medicaid-mngd-care-chip-eqro-contract-yr-2016.pdf

Texas Department of Family and Protective Services. (n.d.). STAR Health – a guide to medical services at CPS. Retrieved from https:// www.dfps.state.tx.us/Child_Protection/Medical_Services/default.asp

Texas Health and Human Services Commission. (n.d.). STAR+PLUS. Retrieved from https://hhs.texas.gov/services/health/ medicaid-chip/programs/starplus

Texas Health and Human Services Commission. (n.d.) STAR+PLUS expansion. Retrieved from https://hhs.texas.gov/services/ health/medicaid-chip/provider-information/expansion-managed-care/starplus-expansion

Texas Health and Human Services Commission. (n.d.). STAR Kids. Retrieved from https://hhs.texas.gov/services/health/ medicaid-chip/programs/star-kids

Texas Health and Human Services Commission. (n.d.). Medicaid Managed Care quality strategy 2012-2016. Retrieved from http://texasrhp9.com/uploads/public/documents/Texas%20Medicaid%20Managed%20Care%20Quality%20 Strategy%202012-2016.pdf

Traylor, C. & Ghahremani, K. (August, 2014). Presentation to the Senate Health and Human Services Committee: SB 7 implementation. Texas Health and Human Services Commission. Retrieved from https://hhs.texas.gov/reports/2014/08/ presentation-senate-health-and-human-services-committee-sb-7-implementation

Texas Health and Human Services Commission. (2017). Texas Medicaid and CHIP in perspective eleventh edition. Retrieved from https://hhs.texas.gov/sites/default/files//documents/laws-regulations/reports-presentations/2017/ medicaid-chip-perspective-11th-edition/11th-edition-complete.pdf

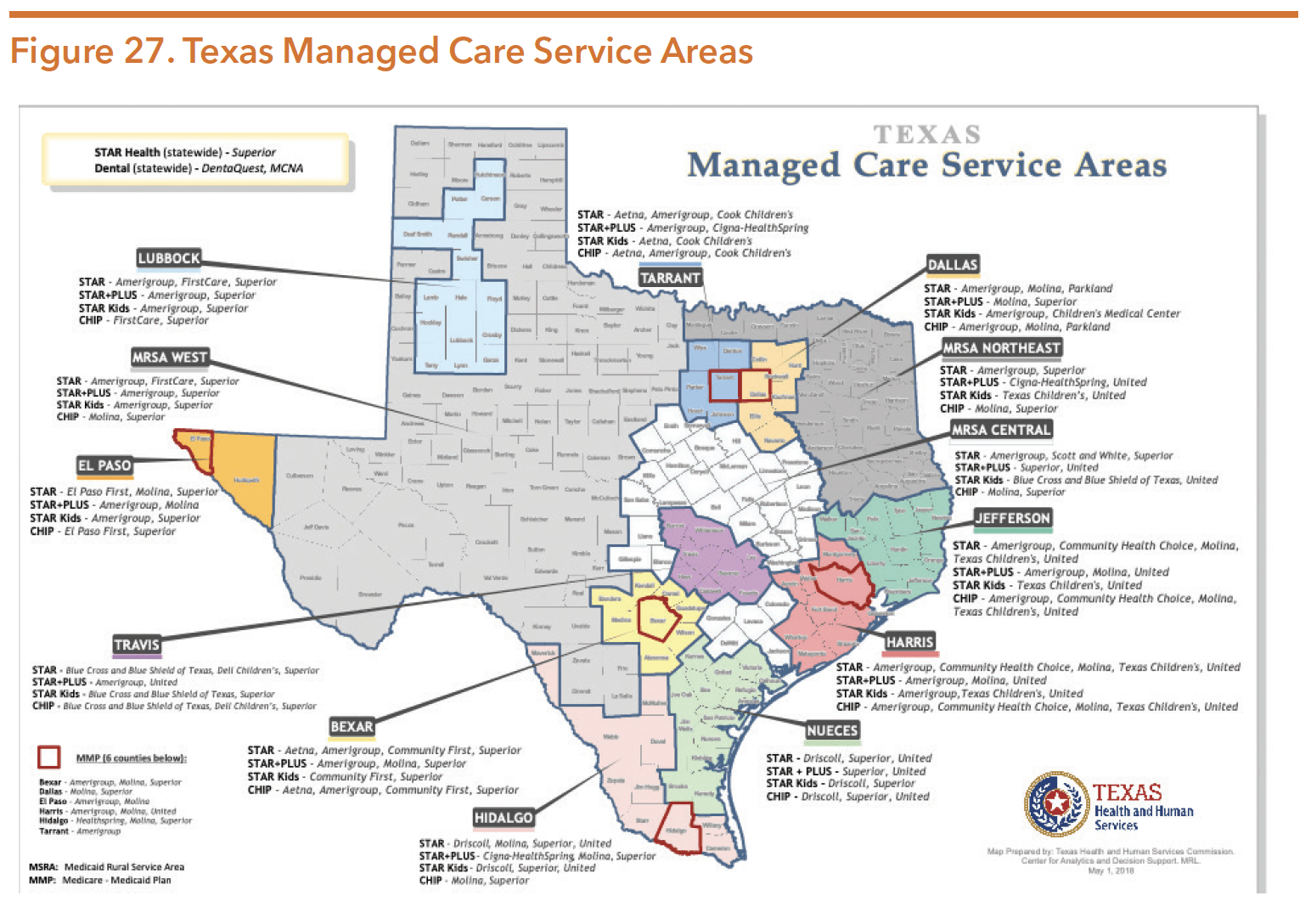

Eighteen MCOs and two dental maintenance organizations (DMOs) provide services to Texas Medicaid and CHIP enrollees. Texas administers services in STAR, STAR+PLUS, STAR Kids, and CHIP in 13 service areas across the state illustrated in Figure 27.

Source: Texas Health and Human Services Commission. (December 2019). Annual report on quality measures and value-based payments. Retrieved from https://hhs.texas.gov/sites/default/files/documents/laws-regulations/ reports-presentations/2019/hb-1629-quality-measures-value-based-payments-dec-2019.pdf

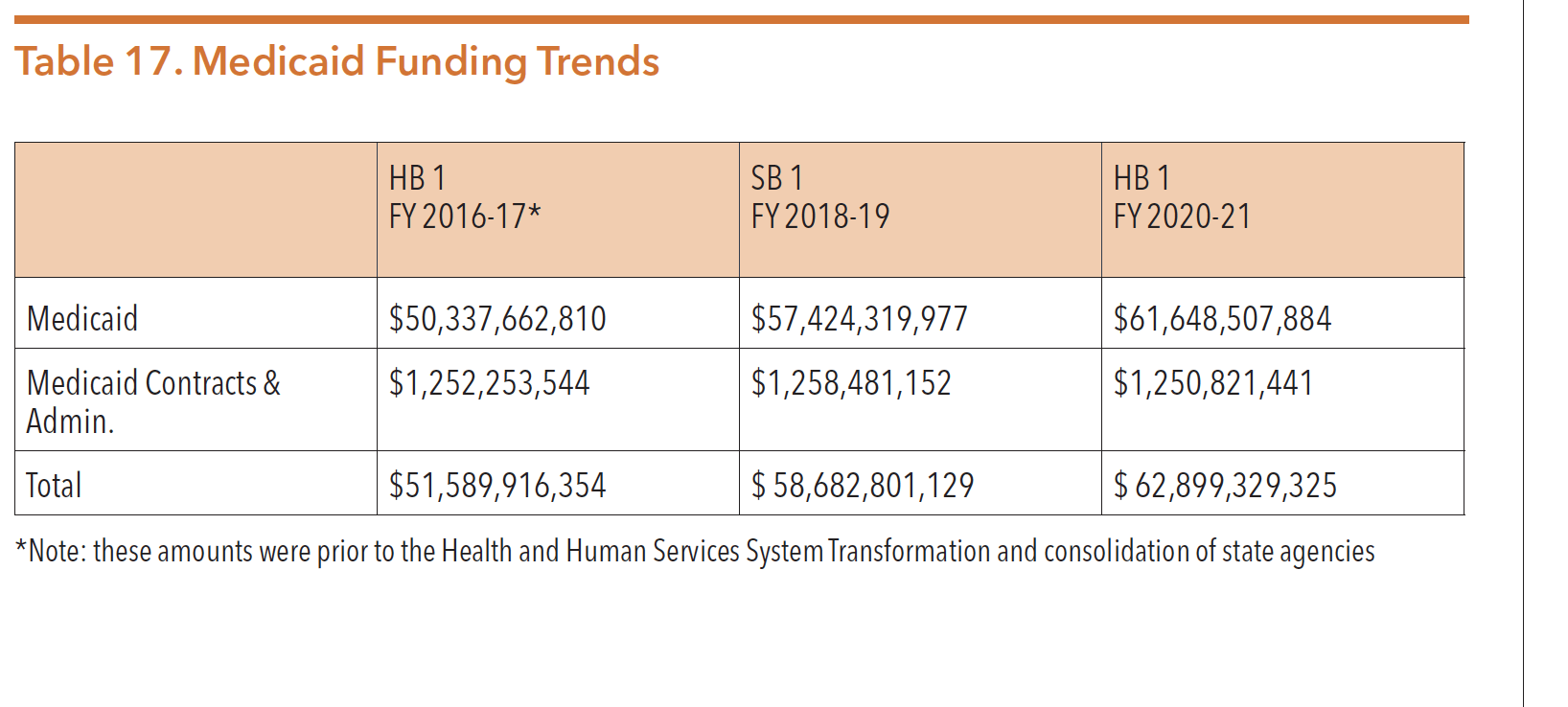

MEDICAID FUNDING

The Texas Medicaid program is jointly funded by the state and the federal government. Medicaid is the largest source of public funding for mental health services nationwide, comprising a quarter of all public behavioral health expenditures.

Table 17 below shows Medicaid funding trends over the last three budget cycles.

Sources: Texas Legislature Online (2019). H.B.1, General Appropriations Act, 86th Legislature, FY 2020-21. Retrieved from https:// capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/86R/billtext/pdf/HB00001F.pdf#navpanes=0

Texas Legislature Online (2017). S.B.1, General Appropriations Act, 85th Legislature, FY 2018-19. Retrieved from https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/85R/billtext/pdf/SB00001F.pdf#navpanes=0

Texas Legislature Online (2015). H.B.1, General Appropriations Act, 84th Legislature, FY 2016-17. Retrieved from https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/84R/billtext/pdf/HB00001F.pdf#navpanes=0

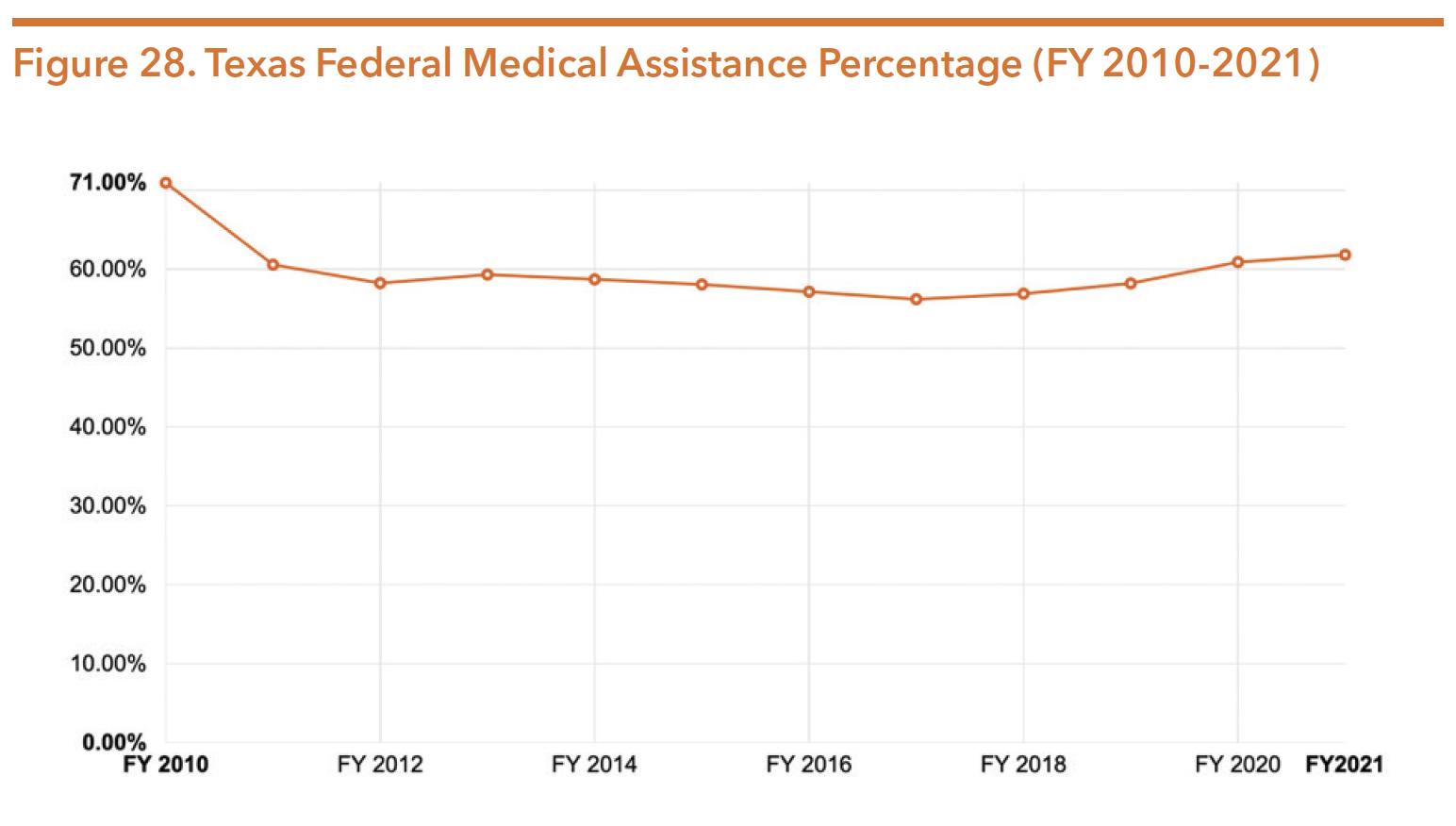

The federal share of the Medicaid program, known as the federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP), is determined on an annual basis and by a formula that takes into account each state’s income per capita compared to the U.S. average. Medicaid is one of the five grant programs administered by the U.S. Health and Human Services that uses the FMAP to determine reimbursements and payments to states.

The FMAP rate is also in-part calculated based on the U.S. Census count completed every 10 years. Small changes in the FMAP can result in millions of dollars in funding fluctuations. Anticipating the next census count to occur following the 86th legislative session, lawmakers filed bills to create a statewide census outreach committee. This initiative failed to pass, as did efforts to include dedicated funds in the budget for grants targeting local outreach efforts. In effort to address concerns from lack of coordinated state efforts, non-profit organizations, grassroots groups, and local governments have partnered on local outreach to ensure Texas has an accurate census count.49 On August 26, 2020, the Texas secretary of state’s office announced an allocation of $15 million from federal funding meant to address COVID, toward an advertising campaign to urge residents to completed the census.

On April 13, 2020, The U.S. Department of Commerce Secretary and the U.S. Census Bureau Director announced a 2020 Census operational plan adjustment due to COVID-19. The announcement stated the new plan “would extend the window for field data collection and self-response to October 31, 2020, which will allow for apportionment counts to be delivered to the President by April 30, 2021, and redistricting data to be delivered to the states no later than July 31, 2021.” However, on August 3, 2020, the Census Bureau Director released a contradictory plan stating field data collection would end by September 30, 2020.

In response, a lawsuit was filed by voting and civil rights groups, as well as local governments, challenging the Trump administration’s order to complete the census count by the end of September. On September 5, 2020, a temporary restraining order was issued by U.S. District Judge Lucy Koh which required the Census Bureau and Commerce Department to continue operations as planned until a later hearing. Despite this injunction, the Commerce Department announced an October 5th end date. As of October 2, 2020, Judge Koh directed the 2020 census counting to continue until October 31st. Additionally, she directed the Census Bureau to send all employees a text message “stating that the October 5, 2020 ‘target date’ is not operative, and that data collection operations will continue through October 31, 2020.” She cited contradictory messages from some supervisors of field employees as the reason for the wide message and that releasing an October 5th ‘target date’ violated her order.

Texas’ Medicaid federal matching rates for FY 2020 and 2021 are 60.89 percent and 61.81 percent; in other words, the state must pay 39.11 percent and 38.19 percent of all costs, respectively. In Texas, Medicaid represents over 25 percent (over $62 billion) of the state budget for 2020-2021.

To illustrate Texas’ trend of federal Medicaid funding, Figure 28 below shows Texas’ FMAP from 2004 to 2021.

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation, State Health Facts. (2020). Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) for Medicaid and multiplier (Timeframe: FY 2010-2020).

On March 18, 2020 the federal government passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) in response to COVID-19. FFCRA immediately increased states’ FMAP percentage by 6.2 percent. This increase is expected to be active through the end of the quarter in which the federal emergency ends and was retroactively applied from January 1, 2020.57 For Texas, this increase resulted in an FMAP of 67.09 percent. In order for Texas to keep the funding, MOE provisions were required, including:

- Refrain from cutting Medicaid eligibility standards or imposing enrollment procedures that are more restrictive;

- Keep all Medicaid enrollees covered who were eligible and receiving services as of March 18, 2020 or who newly enroll during the public health emergency; and

- Cover COVID-19 testing services and treatment in Medicaid, including vaccines, specialized equipment, and therapies, without cost-sharing.

MEDICAID ELIGIBILITY

Medicaid was originally only available to recipients of cash assistance programs such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and Social Security Income (SSI). However, during the late 1980s and early 1990s, the federal government decoupled Medicaid eligibility from the receipt of cash assistance and expanded the program to meet the needs of a broader population, including pregnant women, older adults, and people with disabilities.

In determining program eligibility, Texas considers a variety of factors such as income and family size, age, disability, pregnancy status, citizenship, and state residency requirements. To be eligible for Medicaid in Texas, an individual must meet income and categorical eligibility requirements. Categorical eligibility requires that beneficiaries be part of a specific population group.

There are multiple Medicaid eligibility categories in Texas. Some of the primary categories include:

- Children age 18 and under

- Pregnant women and infants

- Families receiving TANF

- Parents and caretaker relatives

- Individuals receiving SSI

- Adults over age 65 and people with disabilities

- Children and pregnant women who qualify as medically needy

- Former foster youth under 26 years old

- Individuals receiving Medicaid 1915(c) waiver services

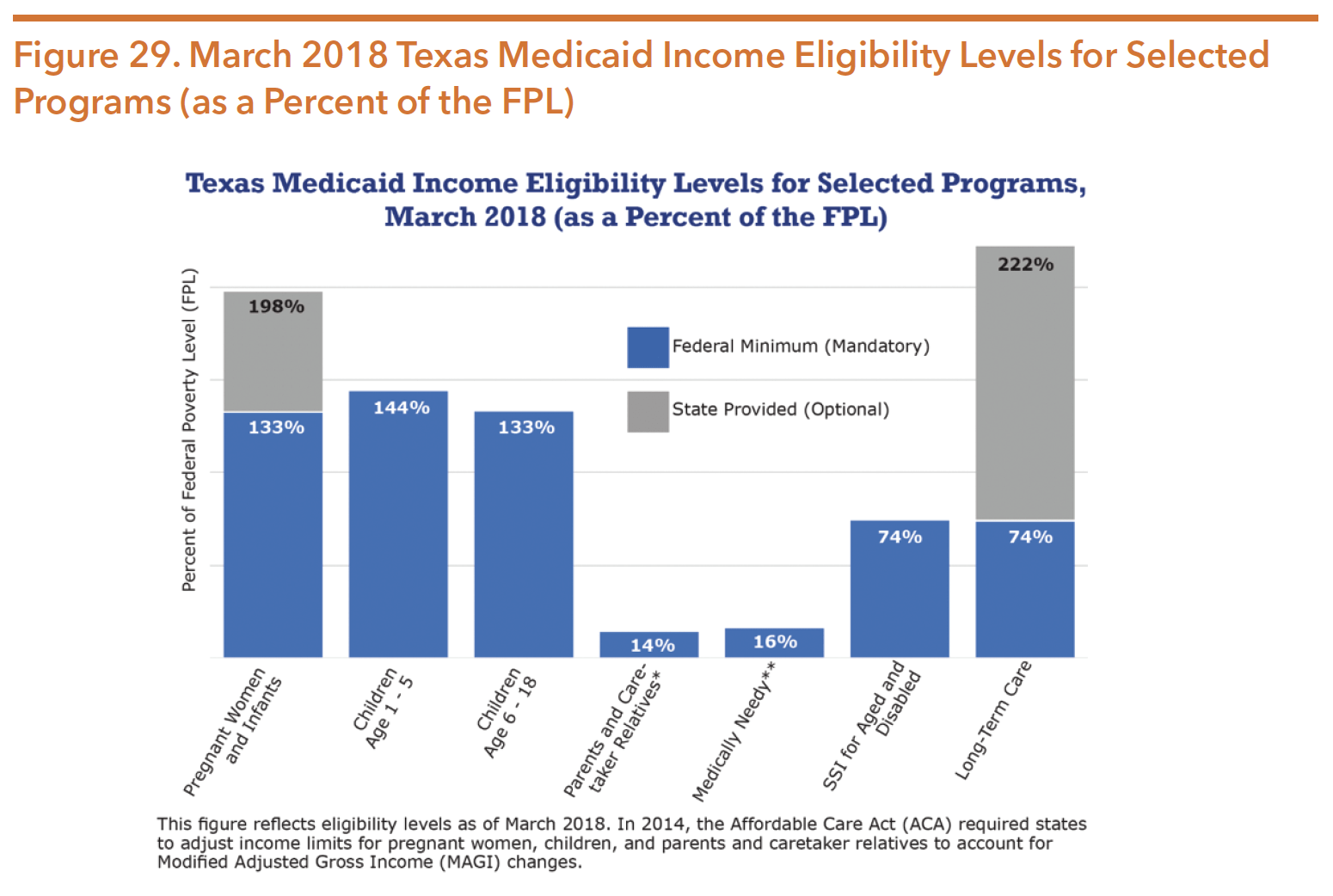

As of January 2019, extremely low-income parents are eligible to receive Medicaid only if their household income is 17 percent of FPL or below, about $307 per month for a family of three. Federal law requires states to cover certain groups and allows states the option to expand eligibility beyond minimum federal standards. Texas Medicaid covers a limited number of optional groups. Because Texas chose not to expand Medicaid eligibility through the Affordable Care Act, the program does not serve the majority of low-income, working adults. Thus, childless adults who are below age 66 and do not have a disability are currently ineligible for Medicaid. Figure 29 shows the income eligibility requirements for each Medicaid category.

Source: Texas Health and Human Services Commission. (2017). Texas Medicaid and CHIP in perspective eleventh edition. Page 4. Retrieved from https://hhs.texas.gov/sites/default/files/documents/laws-regulations/ reports-presentations/2018/medicaid-chip-perspective-12th-edition/12th-edition-complete.pdf

*For Parents and Caretaker Relatives, the maximum monthly income limit in SFY 2018 was $230 for a family of three (one-parent household), which is the equivalent of approximately 14 percent of the FPL.

**For Medically Needy pregnant women and children, the maximum monthly income limit in SFY 2018 was $275 for a family of three, which is the equivalent of approximately 16 percent of the FPL.

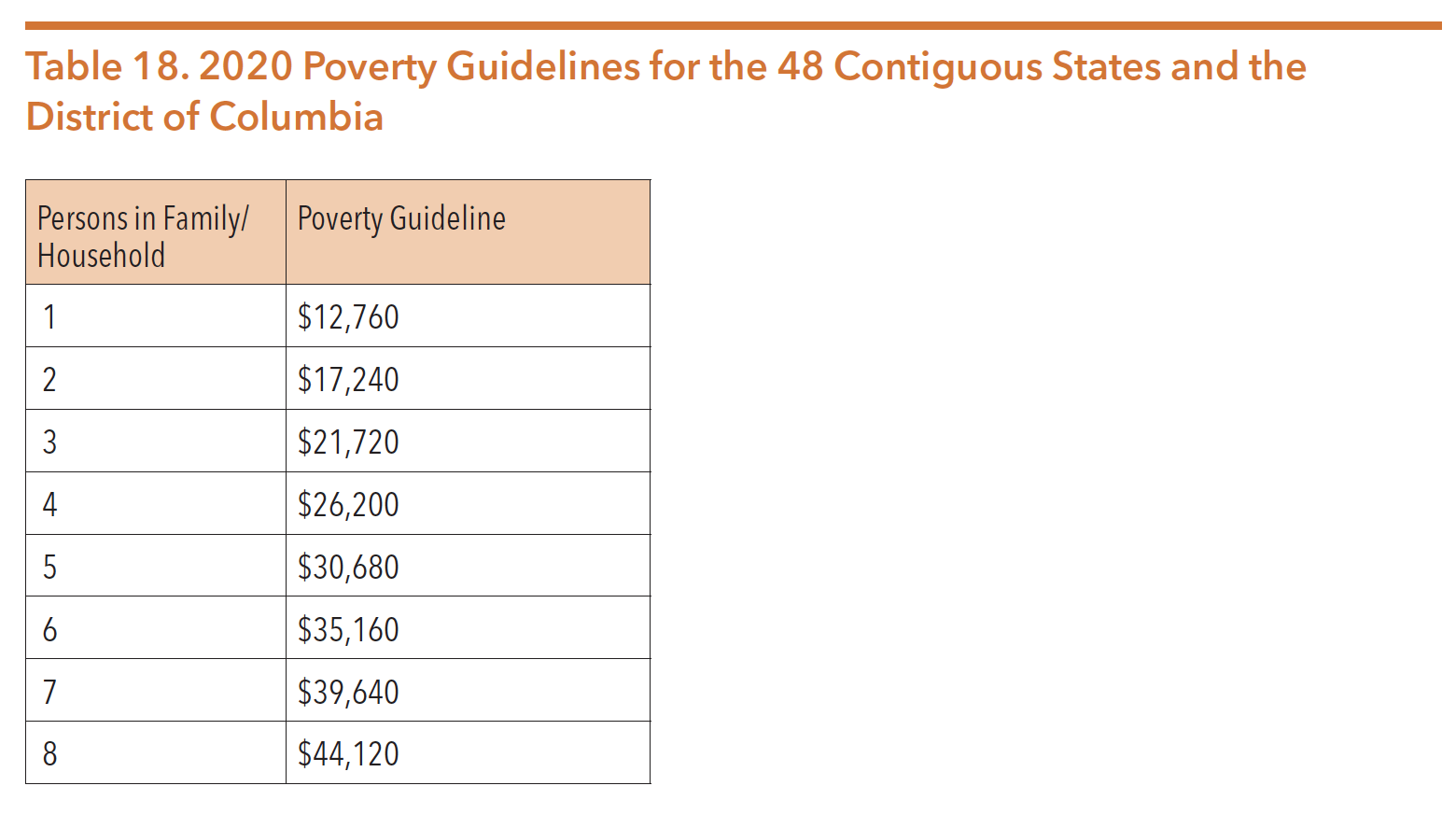

Table 18 below shows the 2020 federal poverty level guidelines for families of households of different sizes.

Source: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. (2020). U.S. federal poverty guidelines used to determine financial eligibility for certain federal programs. Retrieved from https://aspe. hhs.gov/poverty-guidelines.

MEDICAID SERVICES

Medicaid recipients, both adults and children, have access to the mental health and substance use services included in the Medicaid State Plan, such as psychiatric services, counseling, medication, and medication management. Medicaid also funds rehabilitative and targeted case management services by approved providers, primarily the local mental health authorities (LMHAs) operating under HHSC. In addition, HHSC administers several Medicaid-funded waiver programs that offer behavioral health or long-term services and supports to specialized populations. These services and eligibility criteria are further described later in this section.

Behavioral health screening services are an important component of services offered. Following are approved screening services:

- Health and Behavior Assessment and Intervention (HBAI) – eligible to youth 20 and younger designed to identify psychological, behavioral, emotional, cognitive, and social factors that contribute to preventing, treating, or managing physical symptoms. This screening is available to individuals who have underlying physical illness or injury. HBAI services are provided through licensed practitioners of the healing arts (LPHAs) co-located in the same building or office as the PCP to promote integrated care.

- Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) – eligible to individuals 10 years of age and older who are at risk of, or who have a substance use concern. Prevention and early intervention services are eligible to be delivered in community-based services and hospitals.

Approved Medicaid mental health treatment services include:

- Psychiatric diagnostic evaluations and psychotherapy performed by psychiatrists, psychologists, licensed clinical social workers, licensed professional counselors, and licensed marriage and family therapists;

- Psychological and neuropsychological testing performed by psychologists and physicians;

- Inpatient psychiatric care in a general acute care hospital;

- Inpatient care in psychiatric hospitals (for persons age 20 and younger, and age 65 and older);

- Psychotropic medications and pharmacological management of medications;

- Rehabilitative and targeted case management services for people with severe and persistent mental illness or children with severe emotional disturbances;

- Peer Support Services provided by a Certified Peer Specialist;

- Care and treatment of behavioral health conditions provided by a primary care physician; and

- Comprehensive community services for YES waiver participants (see YES waiver information later in this section).

Approved Medicaid substance use services include:

- Assessments to determine an individual’s need for services;

- Individual and group outpatient substance use counseling;

- Outpatient detoxification;

- Residential detoxification;

- Ambulatory detoxification;

- Residential treatment; and

- Peer Support Services provided by a Certified Recovery Coach.

Medication-assisted therapy (MAT) services are approved to be delivered by licensed chemical dependency treatment facilities (CDTFs), opioid treatment programs, or qualifying practitioners. During the 86th legislative session, SB 1586 (West/Klick) expanded prescribing ability. The legislation aligned Texas Medicaid policy with federal law by using the federal definition of “qualifying practitioner,” which includes physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists, certified registered nurse anesthetists, and certified nurse midwives. MAT is primarily used for opioid use conditions but can be provided for alcohol use conditions through the pharmacy benefit. Medications used for MAT are FDA-approved, recommended by the Texas Drug Utilization Review Board, approved by the HHSC Executive Director, and contained in the Preferred Drug List (PDL). Updated PDL and coinciding prior authorization criteria can be found here: https:// www.txvendordrug.com/formulary/prior-authorization/preferred-drugs.

DEMOGRAPHICS OF MEDICAID RECIPIENTS

As of January 2020, 3.5 million Texans across the state received services through Medicaid. A large number of Medicaid recipients are children and young adults, with 27 percent of enrollees are ages 0-5, 35 percent are ages 6-14, and 15 percent are ages 15-20. Non-disabled children make up 69 percent of Medicaid’s client caseload and 30 percent of Medicaid spending. In contrast, individuals who are elderly, blind, or have a disability account for 24 percent of the Medicaid population, but represent 61 percent of total estimated expenditures. Figure 30 displays the population of Medicaid enrollees and program expenditures by age and disability status.

Source: Texas Health and Human Services Commission. (2018). Texas Medicaid and CHIP in perspective twelfth edition. Retrieved from https://hhs.texas.gov/sites/default/files/documents/laws-regulations/reports-presentations/2018/medicaid-chip-perspective-12th-edition/12th-edition-complete.pdf

For more information regarding Medicaid, consult HHSC’s latest edition of Texas Medicaid and CHIP in Perspective, commonly known as the “Pink Book”, available at https://hhs.texas.gov/reports/2018/12/ texas-medicaid-chip-reference-guide-twelfth-edition-pink-book

TEXAS MEDICAID AND HEALTHCARE PARTNERSHIP

The Texas Medicaid and Healthcare Partnership (TMHP) is a group of subcontractors operating under the consulting firm Accenture, which contracts with HHSC to administer the state’s Medicaid fee-for-service claims payments and all Medicaid enrollment activities. All Medicaid managed care providers must first be enrolled in Medicaid through TMHP before they can be credentialed and part of an MCO network. TMHP does not process claims for services provided by MCOs, but it does collect encounter data from MCOs to use for the evaluation of quality and utilization of managed care services.

CHILDREN’S HEALTH INSURANCE PROGRAM (CHIP)

The federal government created the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) in 1997 under Title XXI of the Social Security Act. As with Medicaid, CHIP is jointly funded by state and federal governments. State participation in CHIP requires that the state develop a state CHIP plan for approval by the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS). While CMS allows states to combine their Medicaid and CHIP programs under a single administrative umbrella, Texas administers these programs separately. In September 2017, federal funding for CHIP expired. Initially in 2018, Congress extended CHIP funding for six years as part of a short-term resolution. Later during budget negotiations, Congress extended CHIP funding further through fiscal year 2027. Funds have been allocated for the first six years of the extension. Specific allotments were not included for FY 2024-27, but instead specifies that “such sums” as necessary will be available. Changes made that will impact the future of the program include:

- A decrease in the enhanced FMAP (as provided by ACA) from the current 23 percentage point enhancement to 11 in 2020 and down to traditional FMAP levels in 2021 and beyond;

- On October 1, 2019, states with CHIP eligibility levels above 300 percent FPL will have the option to lower eligibility to 300 percent FPL. States with CHIP eligibility levels below 300 percent (including Texas, 201 percent FPL) must maintain current eligibility levels until September 30, 2027; and

- Beginning in FY 2024, states will be required to annually report a set of core pediatric quality measures to CMS that were previously voluntary, including performance of primary care access and preventative care and behavioral health care.

CHIP FUNDING

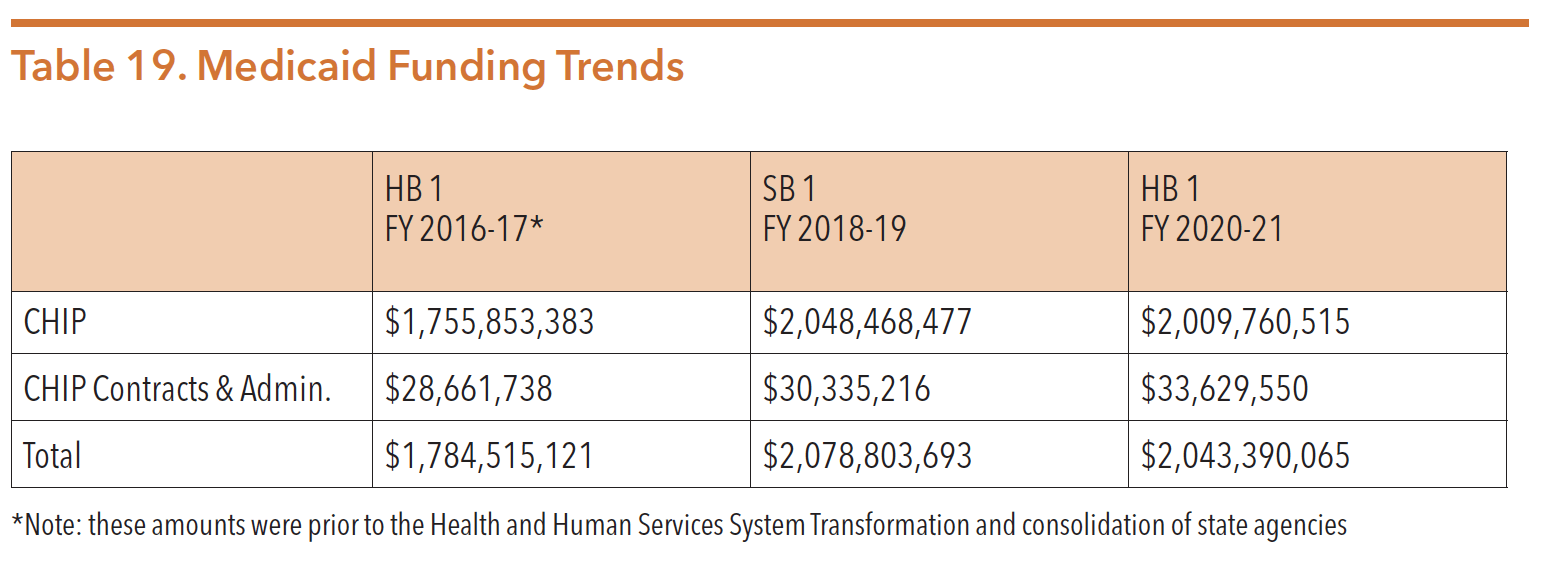

Table 19 below shows CHIP funding trends over the last three budget cycles.

Sources: Texas Legislature Online (2019). H.B.1, General Appropriations Act, 86th Legislature, FY 2020-21. Retrieved from https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/86R/billtext/pdf/HB00001F.pdf#navpanes=0

Texas Legislature Online (2017). S.B.1, General Appropriations Act, 85th Legislature, FY 2018-19. Retrieved from https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/85R/billtext/pdf/SB00001F.pdf#navpanes=0

Texas Legislature Online (2015). H.B.1, General Appropriations Act, 84th Legislature, FY 2016-17. Retrieved from https://capitol.texas.gov/tlodocs/84R/billtext/pdf/HB00001F.pdf#navpanes=0

CHIP ELIGIBILITY

The federal government developed CHIP to provide a health insurance coverage option for children whose families had too much income or too many assets to qualify for Medicaid, but not enough to afford private insurance through their employer or through the individual market. CHIP is available to children under age 19 who are ineligible for Medicaid, who are living in households with an income at or below 201 percent of the FPL, and who have been uninsured for at least 90 days or have a good cause exemption. For these children, CHIP provides access to health care, including inpatient and outpatient mental health and substance use services. In contrast to Medicaid, CHIP requires cost sharing through enrollment fees and co-payments based on a family’s income. Families may pay up to a $50 enrollment fee for a 12-month period. Texas also opted to administer a CHIP perinatal program which covers perinatal services, including labor, delivery, and postpartum care for women and their unborn child with household incomes of up to 202 percent of the FPL. The majority of CHIP clients are over age five, with 11 percent being between the ages of 6 and 14, and 41 percent between the ages of 15 and 18.

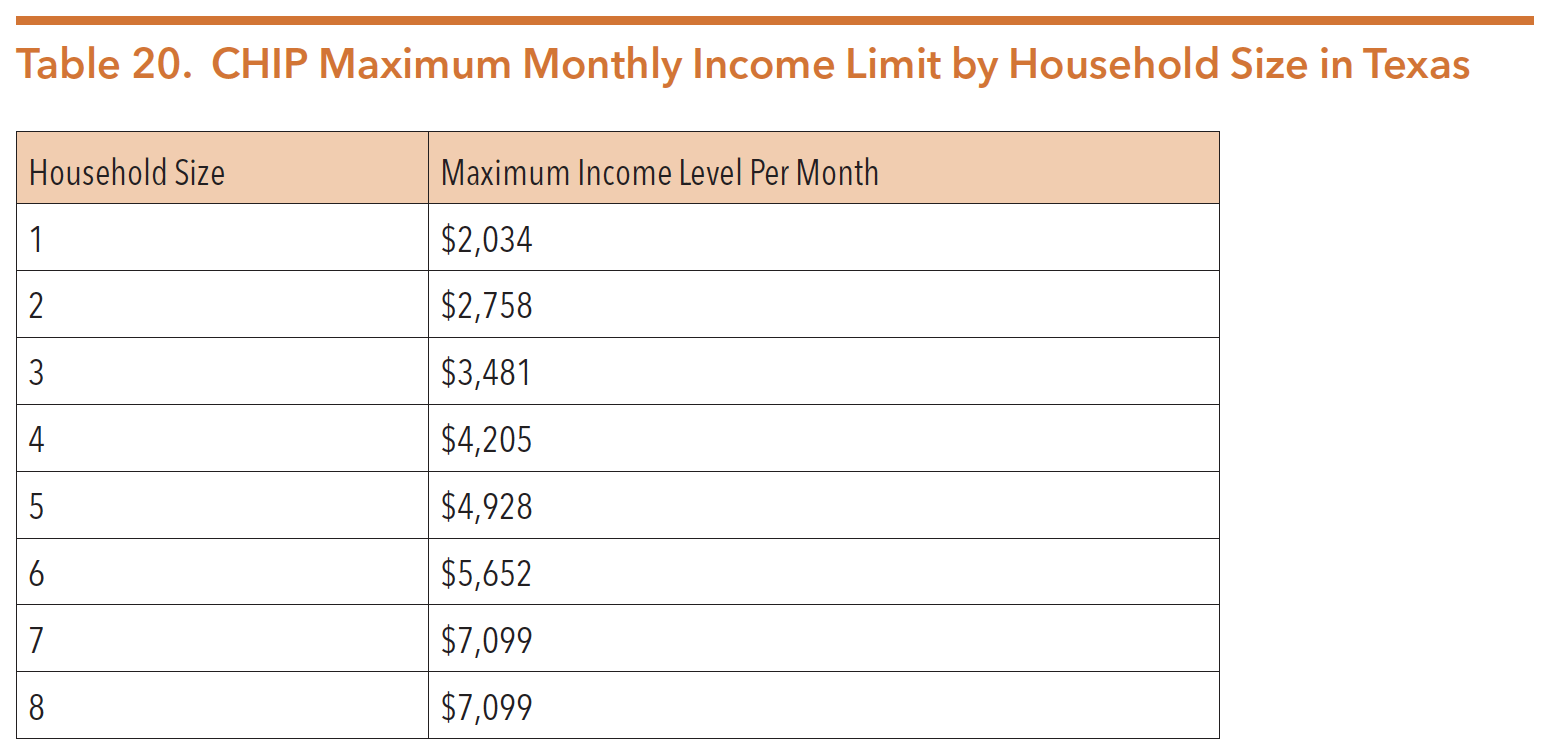

The table below provides monthly household income limits for CHIP eligibility in Texas.

Source: Texas Health and Human Services Commission. (2018). Texas Medicaid and CHIP in perspective twelfth edition. Retrieved from https://hhs.texas.gov/sites/default/files/documents/laws-regulations/reports-presentations/2018/ medicaid-chip-perspective-12th-edition/12th-edition-complete.pdf

Figure 31 below shows the monthly CHIP enrollment numbers in Texas from 2015 to 2020.

Note: Data is from January of each year.

Source: Texas Health and Human Services Commission. (September 2020). CHIP monthly enrollment detail (September 2014-June 2020) (XLS) [data file]. Retrieved from https://hhs.texas.gov/about-hhs/records-statistics/data-statistics/healthcare-statistics

CHIP SERVICES

The CHIP program offers many of the same services to children as those enrolled in Medicaid, including mental health care and substance use services.

Mental health treatment services include:

- Neuropsychological and psychological testing;

- Medication management;

- Rehabilitative day treatments;

- Residential treatment services;

- Sub-acute outpatient services (partial hospitalization or rehabilitative day treatment)

- Skills training; and

- Inpatient mental health services in a free-standing psychiatric hospital, psychiatric unit of a general acute care hospital, or state-operated facility.

Additionally, the following substance use treatment services are available to CHIP members:

- Inpatient treatment, including detoxification and crisis stabilization;

- Outpatient treatment services, including group and individual counseling;

- Intensive outpatient services;

- Residential treatment;

- Partial hospitalization; and

- Prevention and intervention services by physician and non-physician providers.

- Medication assisted treatment (MAT) is not a covered benefit through CHIP, however can be provided as a prescription drug benefit

HHSC QUALITY OF CARE REVIEW AND THE HEALTHCARE QUALITY PLAN

Texas contracts with the University of Florida Institute for Child Health Policy as the external quality review organization (EQRO) to review the Texas Medicaid Managed Care programs. The annual quality of care evaluation compares Texas’ performance to the national Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set standards, or alternatively to benchmarks that HHSC establishes. The national Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) standards are used across the country to measure performance within health care, including behavioral health services.

The latest review of Texas managed care programs for FY 2018 was released in May 2019. The report found that HHSC has done significant work to improve the quality of care within behavioral health. HHSC asked the EQRO to complete quarterly topic reports examining the following:

- Factors leading to potentially preventable service use among Medicaid members with co-occurring behavioral and physical health conditions,

- Ways to integrate behavioral and physical health services, and

- Investigations of opioid prescribing measures.

The review also included evaluations and surveys of STAR, STAR+PLUS, STAR Health, and STAR Kids. A number of behavioral health findings offer the opportunity for improvement including:

- In all programs, the rates of members who were hospitalized for mental illness and received follow-up visits (within 30 days and within 7 days) were low compared to national benchmarks and state standards.

- Among health plans, the percentage of in-network providers excluded from members’ lists to schedule an appointment due to “no answer after three attempts” or “wrong number/unreachable provider” ranged from 48 percent to 61.1 percent.

- Providers identified psychiatric care as the most difficult referral type for both children and adult patients, with referrals for both children and adults frequently taking longer than one month.

- MCOs noted that issues of network access or adequacy included shortages of behavioral health providers and other specialists.

- Based on the findings, the report offered a number of recommendations including:

- Programs should give considerable attention to efforts to establish, improve, and monitor behavioral and physical health care integration practices.

- Recruitment of specialized providers should include negotiating reasonable and appropriate payment rates.

- MCOs should improve access to care through transportation assistance and telemedicine services in rural areas where shortages of behavioral health and specialist providers are common.

Improved performance, improved measurement of performance, and payment mechanisms based on performance appear to be a priority for both the legislature and HHSC. There are six strategic priorities incorporated in the HHSC Healthcare Quality Plan as required by SB 200 (84th, Nelson/Price) including:

- Keeping Texans healthy

- Providing the right care in the right place, at the right time

- Keeping patients free from harm

- Promoting effective practices for chronic disease

- Supporting patients and families facing serious illness

- Attracting and retaining high performing providers and other healthcare professionals

SB 200 (84th, Nelson/Price) granted the HHS Executive Commissioner authority to establish the Value Based Payment and Quality Improvement Advisory Committee. The Committee submits a report to the Texas Legislature and to HHSC each December, including recommendations on “value-based payment and quality improvement initiatives to promote better care, better outcomes, and lower costs for publicly funded health care services.” The committee’s report to the 86th legislature included the following behavioral health recommendations:

- Sustaining innovative behavioral health models, including DSRIP projects funded through the 1115 waiver and use of the Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics (CCBHC) model;

- Expanding substance use treatment;

- Studying value-based options for substance use identification; and

- Recommend Medicaid to evaluate bundle rates for MAT for more efficiency. (Note: The SAPT block grant reimbursement rate includes counseling in addition to medication, whereas Medicaid has separate reimbursement for medication and counseling).

More information on the committee can be found at https://hhs.texas.gov/about-hhs/leadership/advisory-committees/ value-based-payment-quality-improvement-advisory-committee

In addition to the Value Based Payment and Quality Improvement Advisory Committee, HHSC has a number of value-based care programs and initiatives, including:

- MCO/DMO Pay-for-Quality (P4Q)

- MCO Alternative Payment Models (APM)

- Hospital Quality Payment Program

- DSRIP Program

- Nursing Home Quality Incentive Payment Program (QIPP)

- Uniform Hospital Rate Increase Program (UHRIP)

- Network Access Improvement Program (NAIP)

- HHS Quality Webpage

- Texas Healthcare Learning Collaborative Portal

- Advisory Committees and Workgroups

The Texas Legislature continues to direct HHSC to prioritize value and transparency in the Medicaid program. Among the budget riders included in Article II of HB 1, Rider 43 required HHSC to implement an incentive program that automatically enrolls a greater percentage of Medicaid recipients who have not selected a managed care plan into a plan based on quality of care, efficiency, and effectiveness of service provision and performance. Appropriations for FY 2021 were contingent on HHSC implementing this program by September 1, 2020

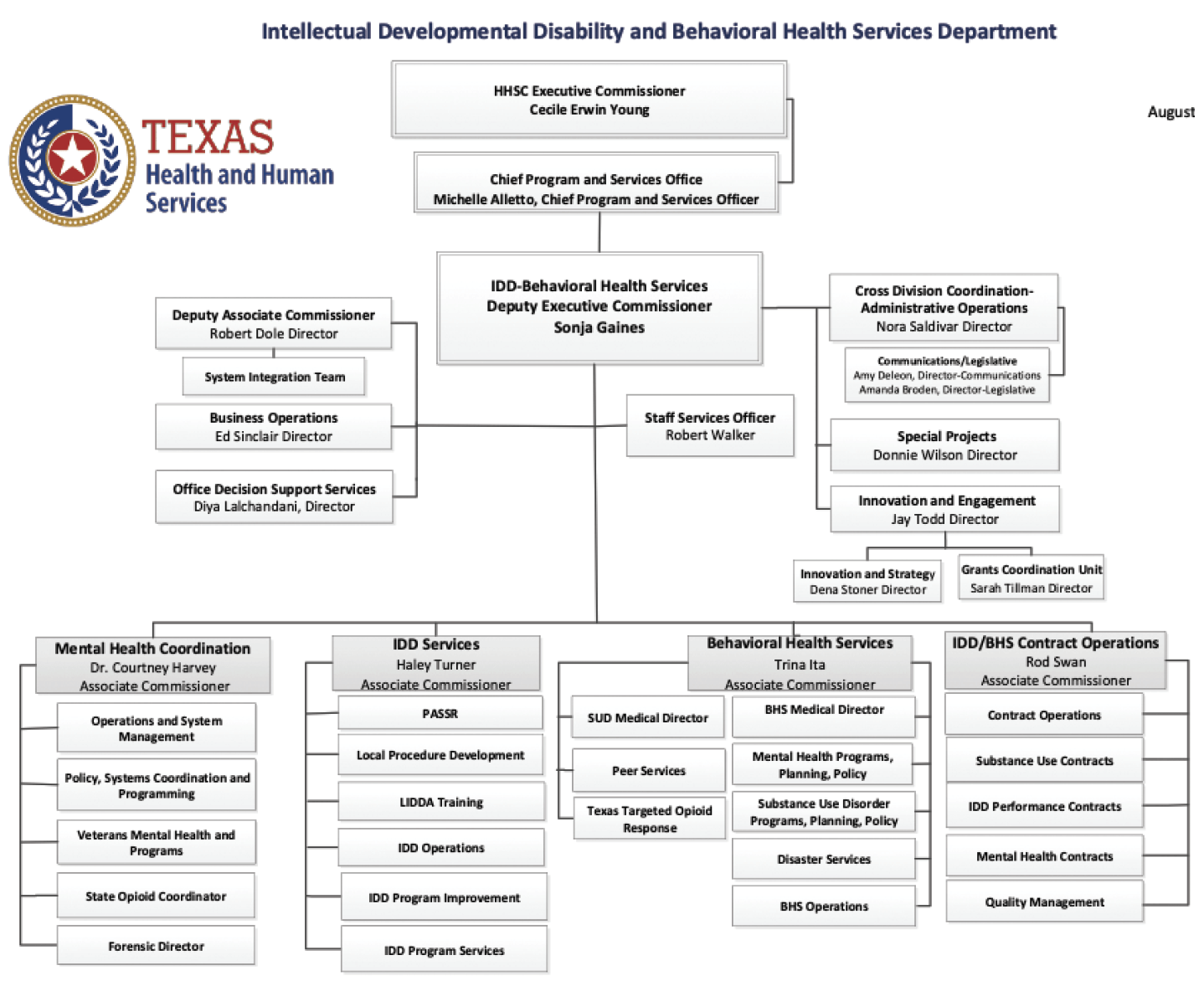

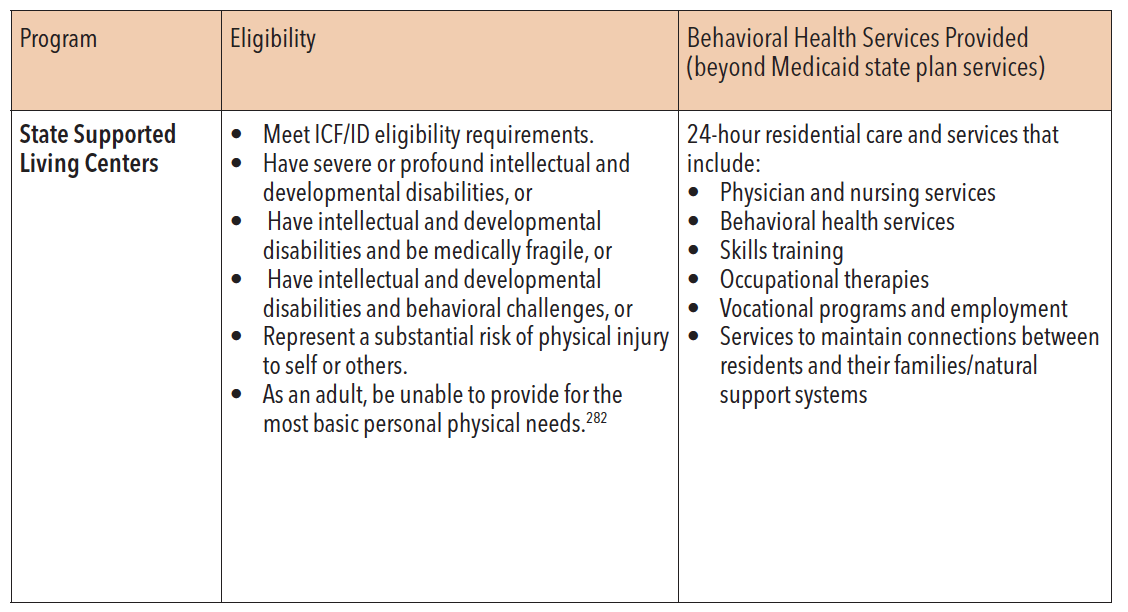

Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities & Behavioral Health Services Division

Source: Texas Health and Human Services Commission. (August 2020). Public Information Request, October 2020.

The Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities and Behavioral Health Services Department combines responsibility for community services for individuals with intellectual and other developmental disabilities and those living with mental health and substance use conditions under one deputy executive commissioner authority.

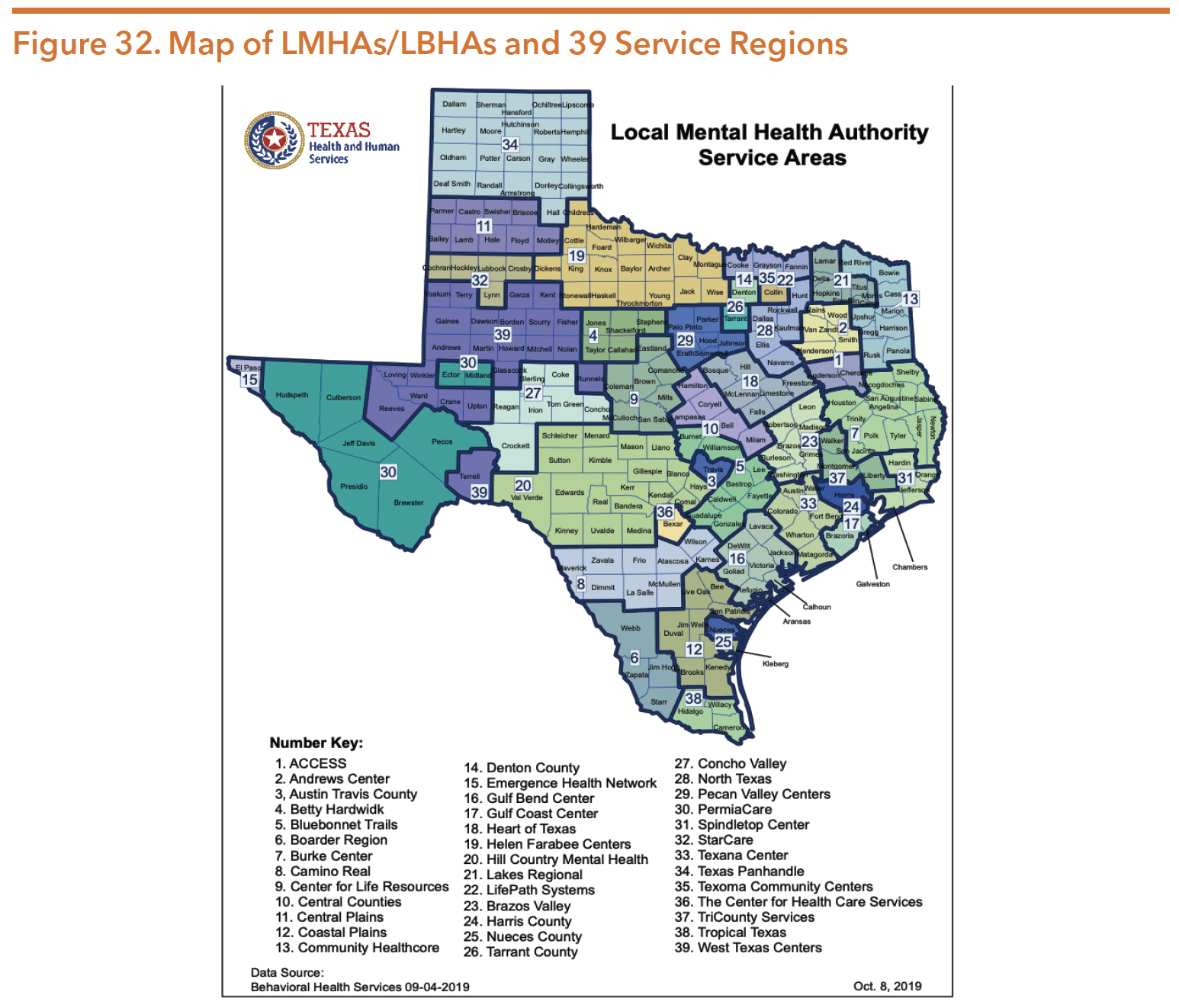

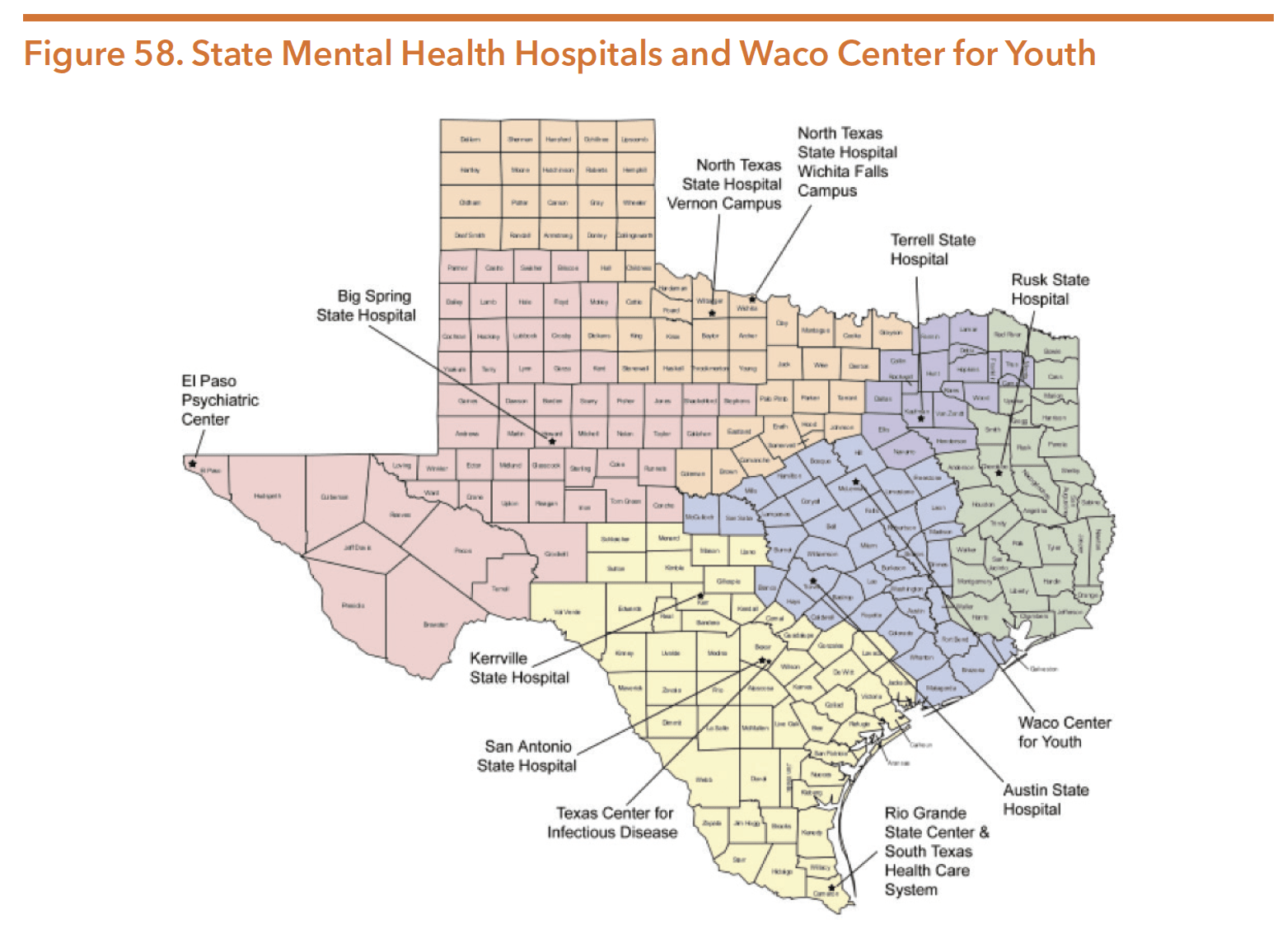

Public behavioral health services are mainly comprised of community mental health, substance use, and inpatient psychiatric services. These services are provided to residents through the 39 local mental health authority (LMHA) regions and 20 Regional Health Partnerships (RHPs) in all of Texas’ 254 counties. The Medical and Social Services Division has oversight responsibility for community behavioral health services while the Health and Specialty Care has oversight of state-run and contracted inpatient services.

MENTAL HEALTH

HHSC prioritizes access to treatment and services for individuals with a serious mental health condition, who are eligible for Medicaid, determined to be indigent, or who fall under the priority populations criteria (major depression, bipolar, and schizophrenia). Resources, eligibility for services, and service delivery systems are the primary determinants of the accessibility and quality of services. Texas continues to seek ways to improve access so that individuals with mental health and substance use conditions can receive the level of care and support that are clinically appropriate for their level of need. HHSC maintains a central website, www.mentalhealthtx. org, to improve access to information. Individuals can enter their zip code and find available mental health and substance use services in their area.

Since November 2018, leadership from leadership from Intellectual and Developmental Disability and Behavioral Health Services, the Health and Specialty Care System, Medicaid, Regulatory, and Aging Services Coordination have worked together to form the HHSC Continuum of Care Workgroup. The Workgroup is responsible for addressing issues and solutions to improve the continuum of care within behavioral health services across the human services system. The objectives of the work group include:

- Ensuring the most effective and efficient communication and coordination between state hospitals and local mental health authorities (LMHAs), to provide seamless care;

- Identifying gaps and barriers to continuity of care, and more specifically to successful discharge from state hospitals; and

- Identifying short-term and long-term goals to address the identified gaps and barriers.

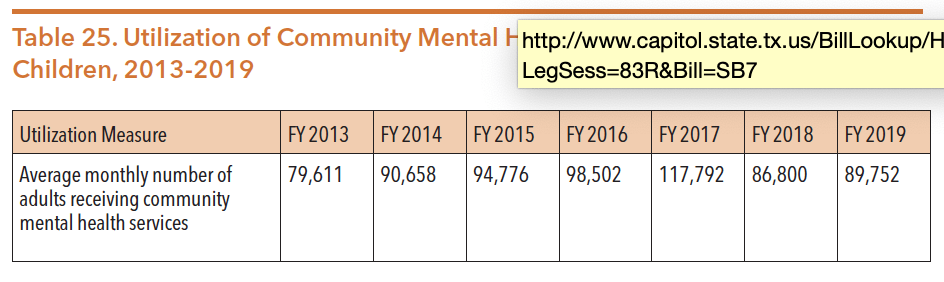

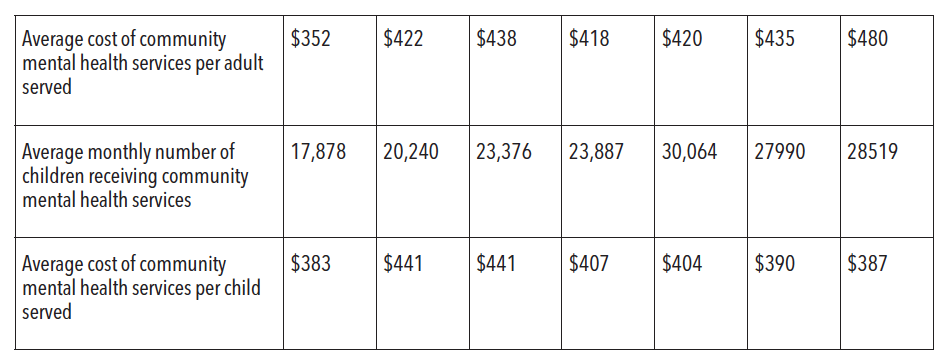

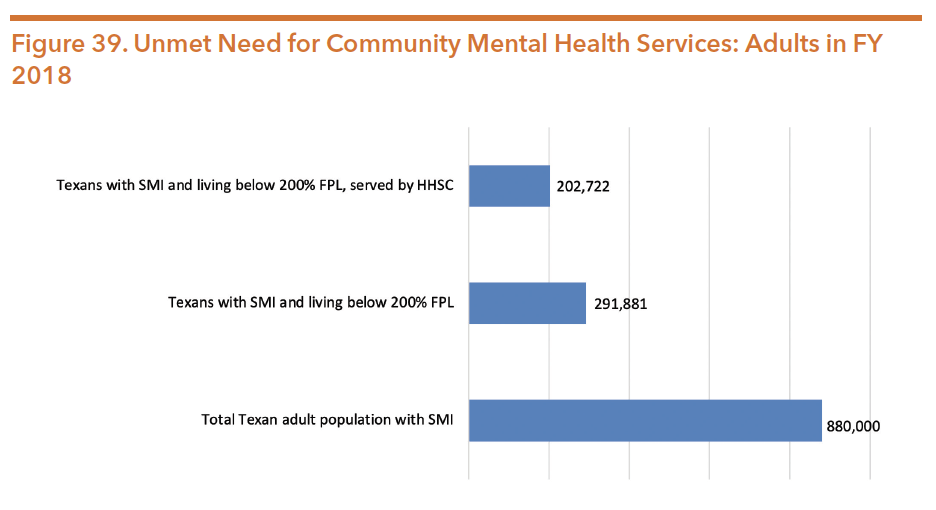

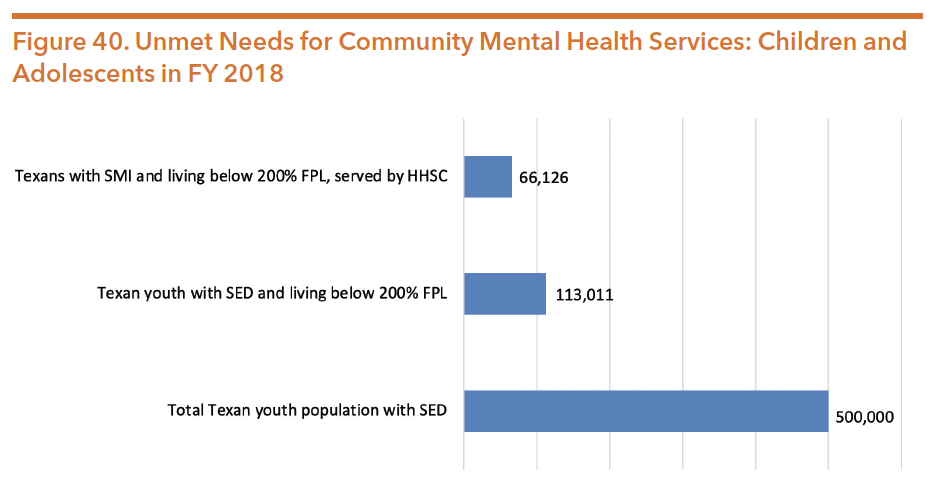

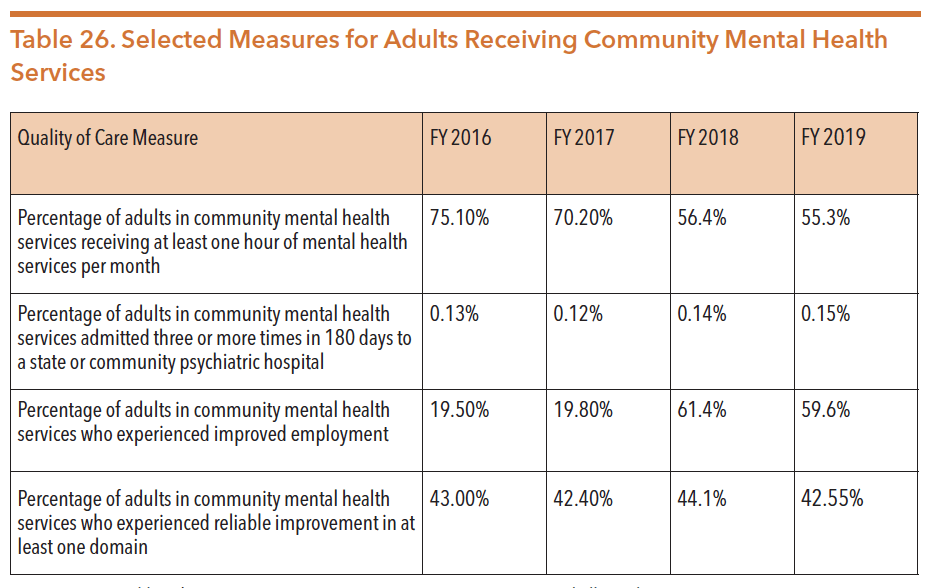

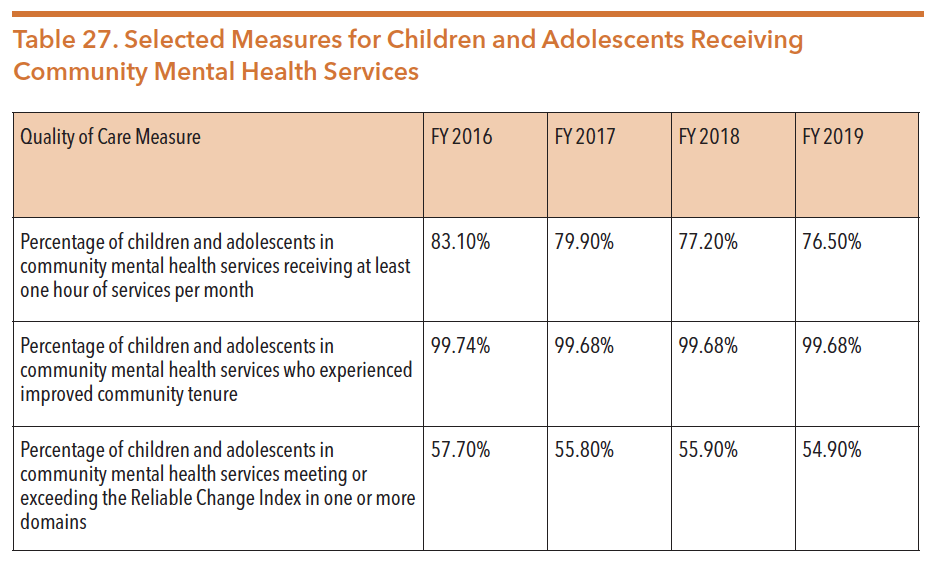

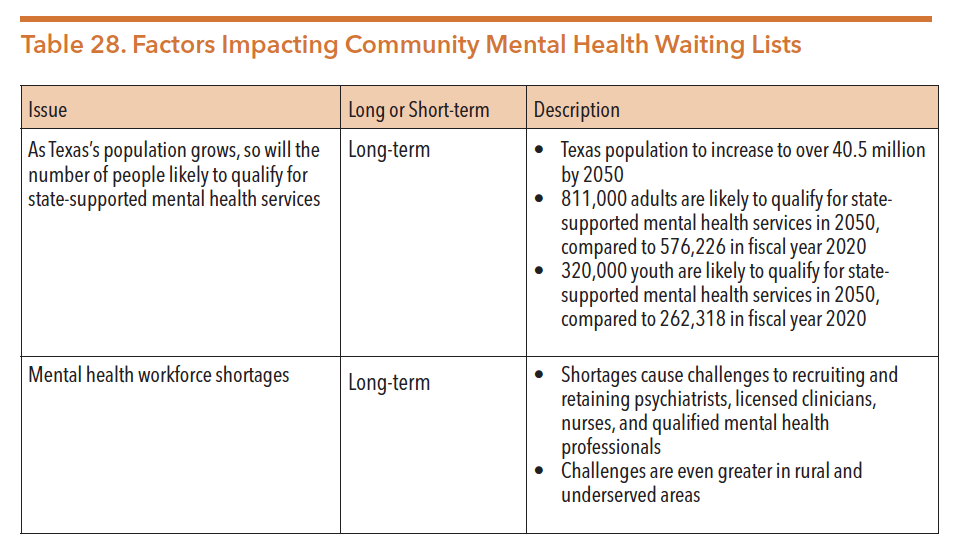

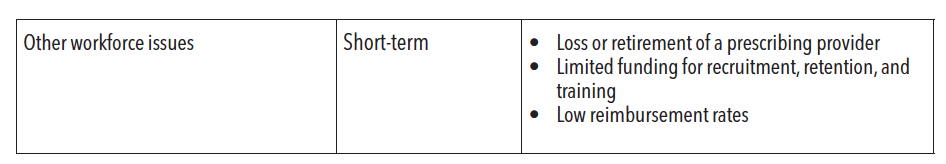

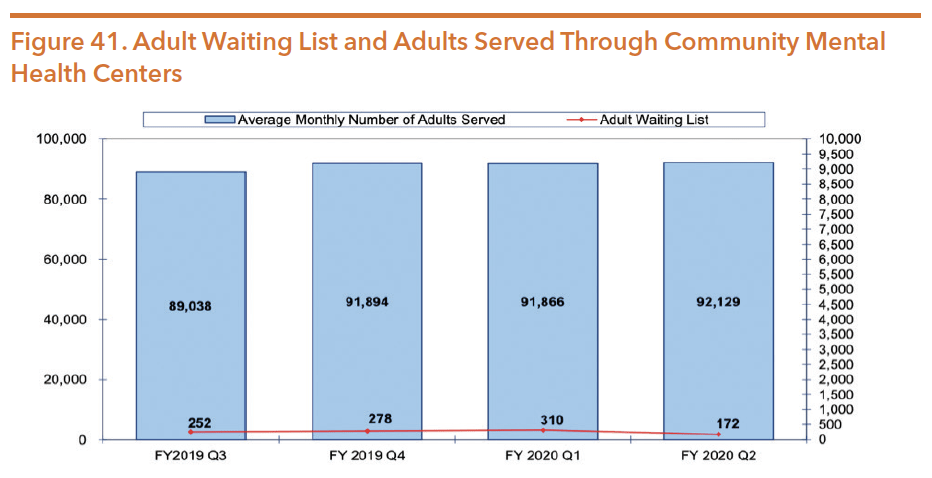

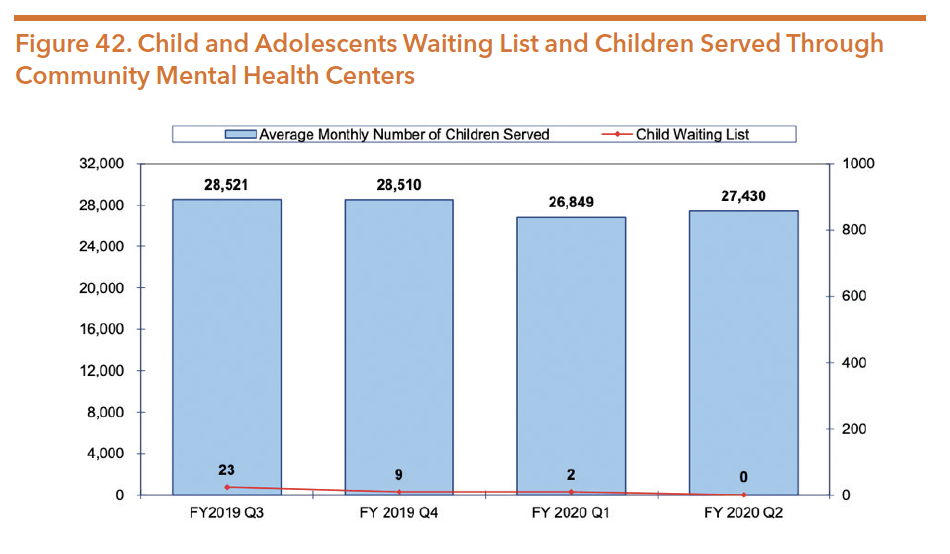

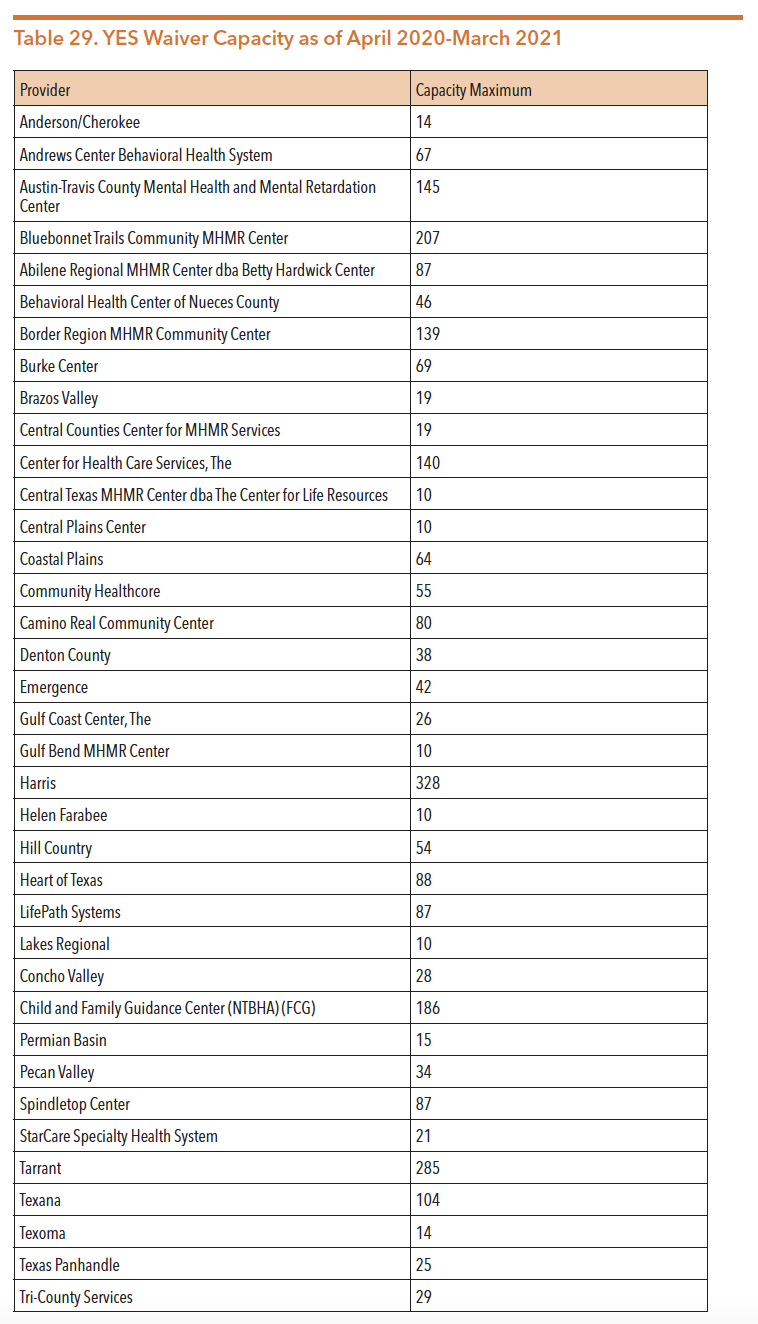

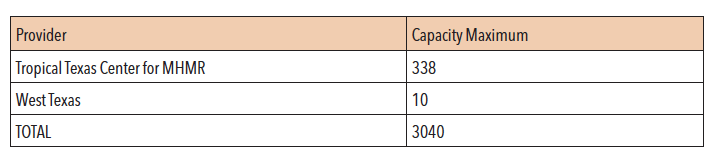

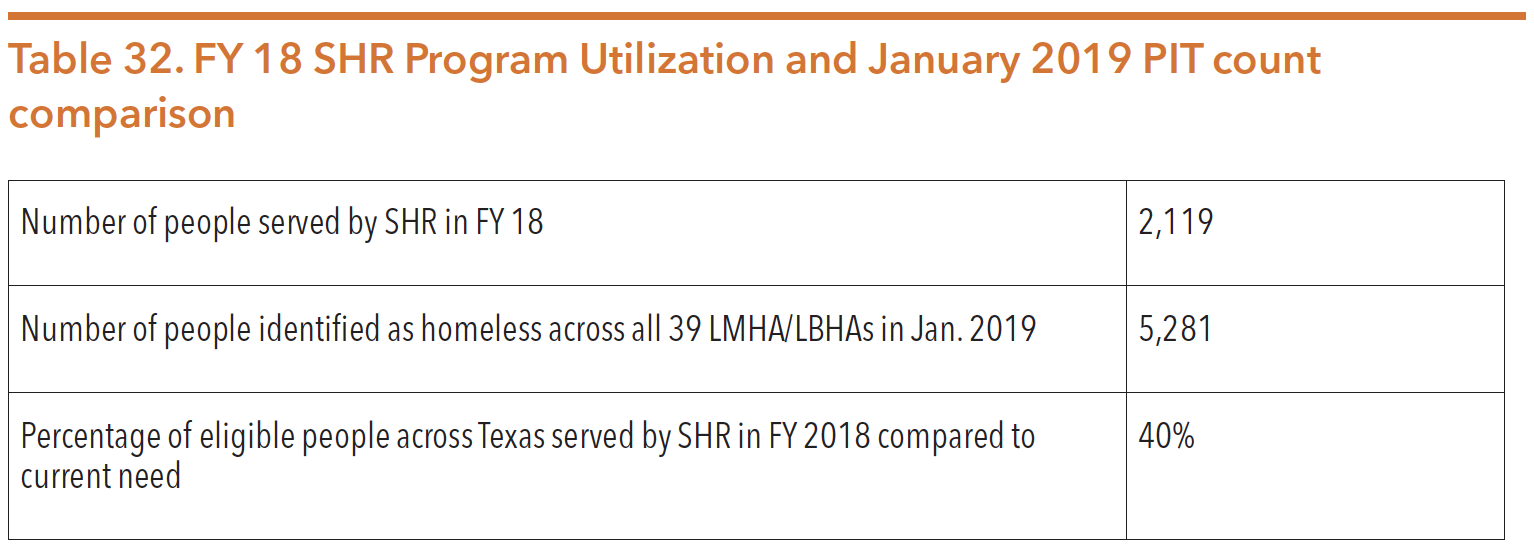

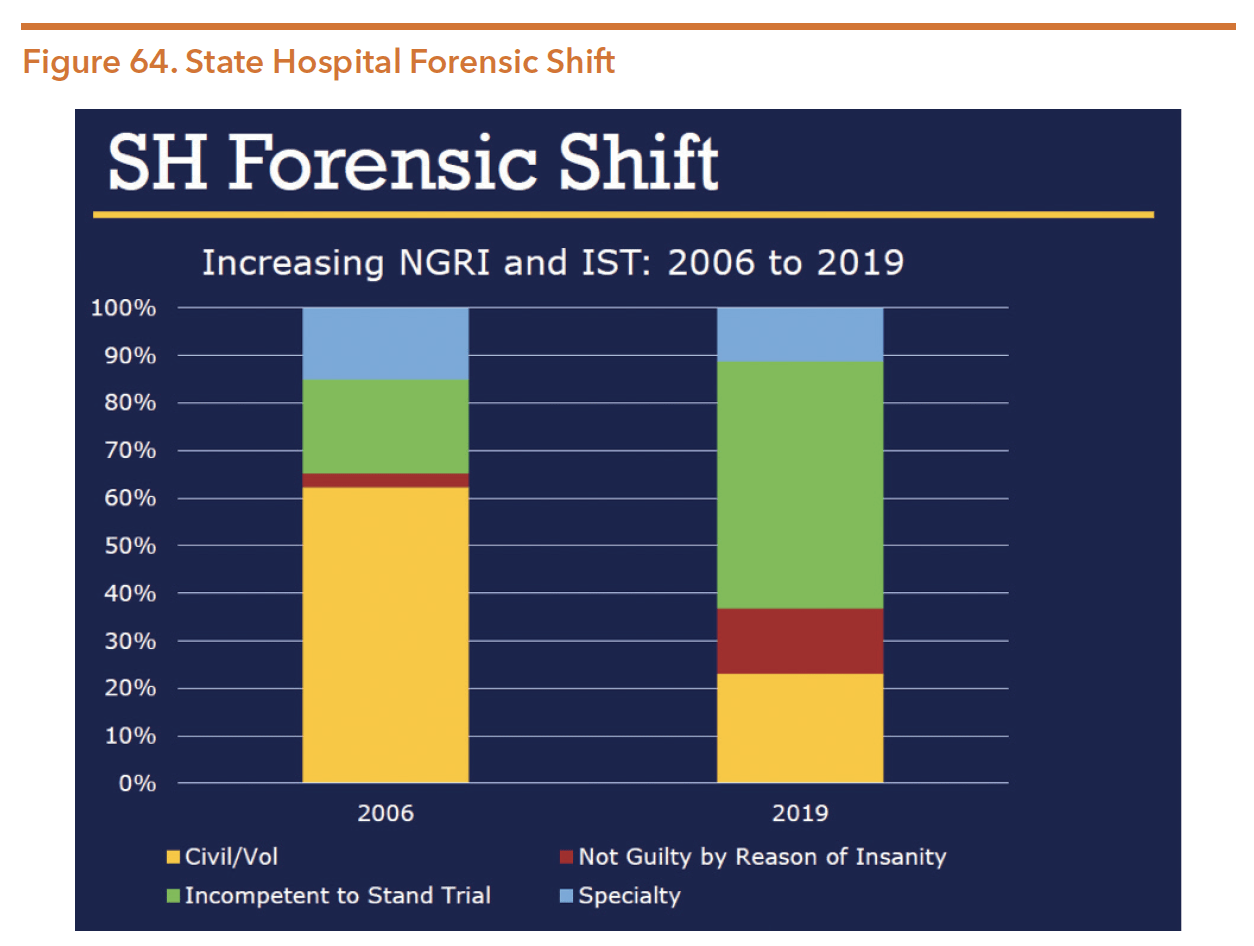

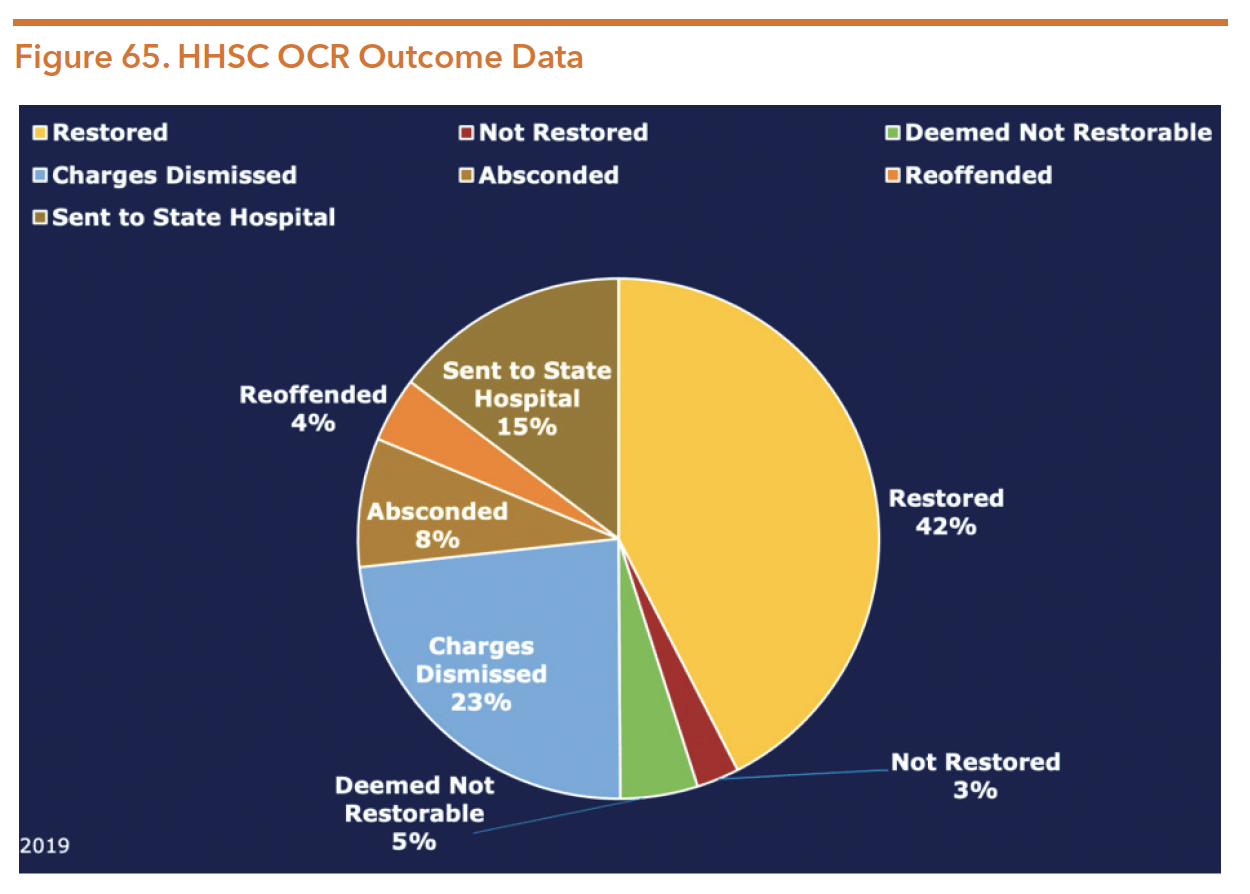

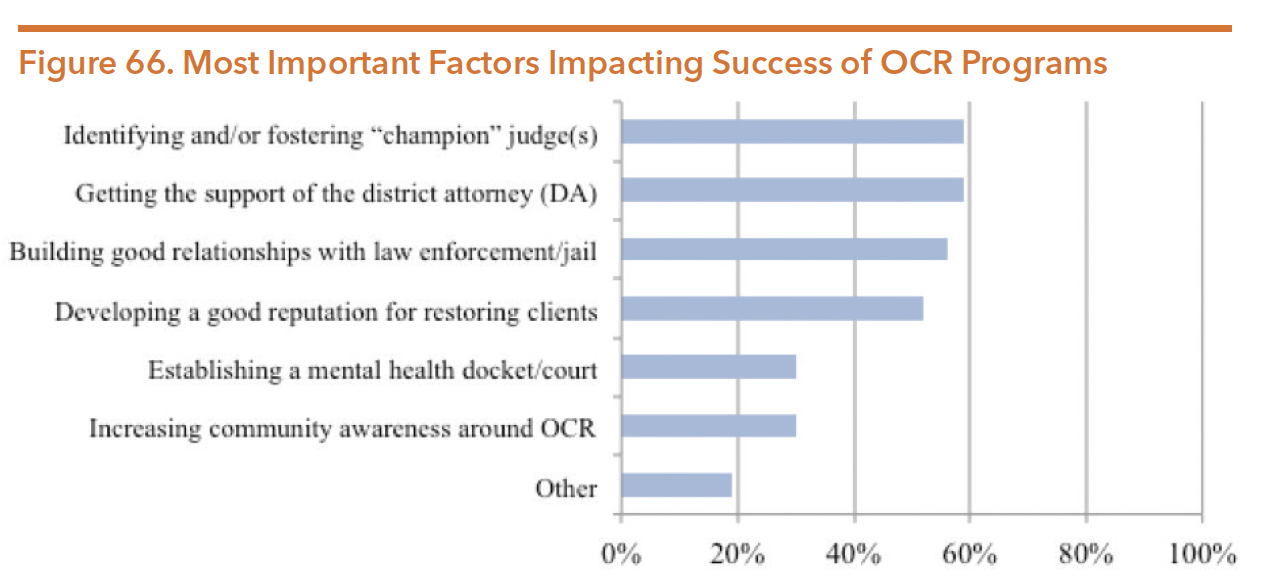

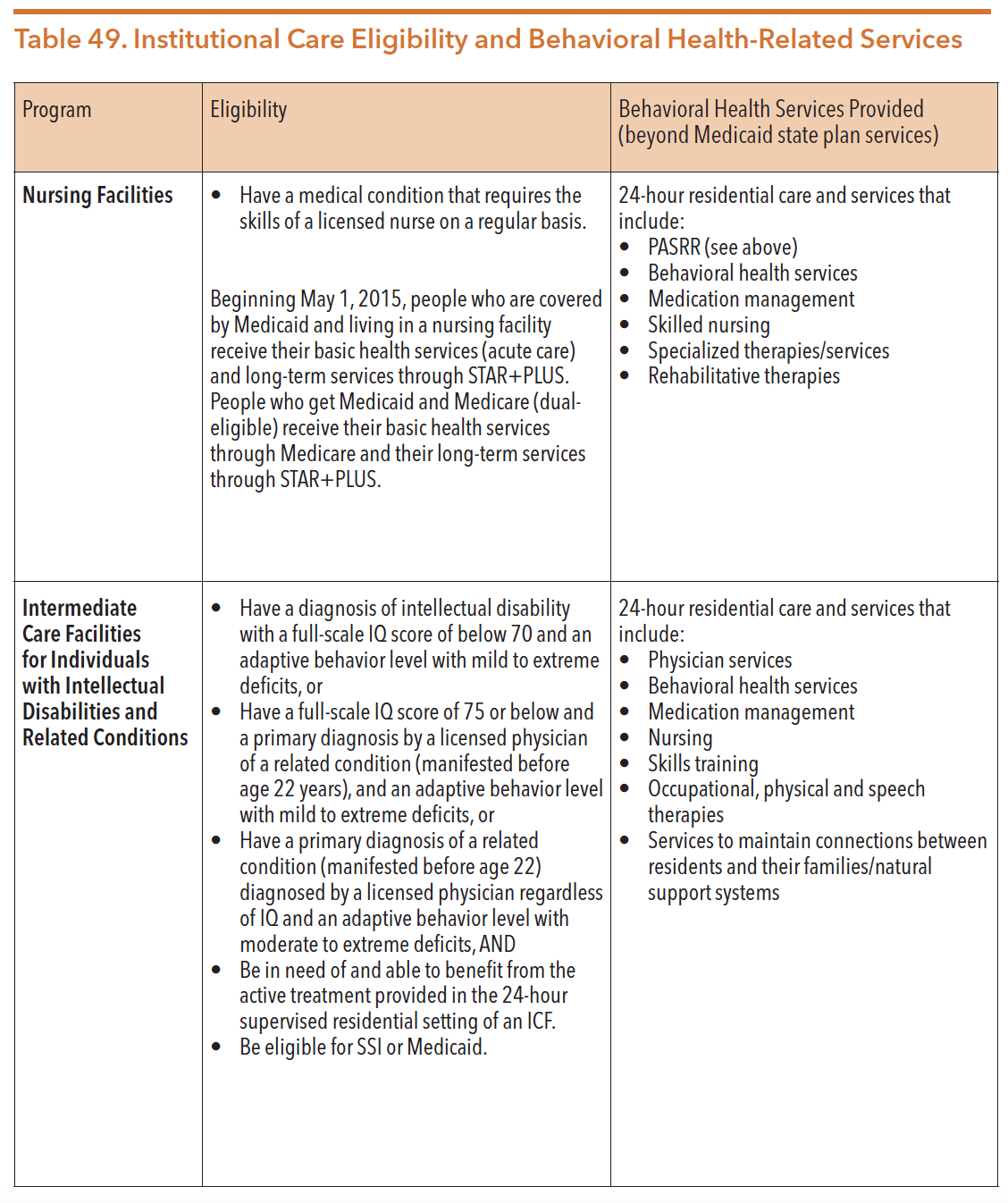

As of October 2019, the Workgroup made progress on several initiatives to meet these goals including: