*Note: If you find the text on some of the images blurry or hard to read, right-clicking the image and then selecting “open image in new tab” may improve the issue.

HHSC Blueprint for a Healthy Texas

In October 2019, HHSC unveiled the Texas Health and Human Services (HHS) Blueprint for a Healthy Texas, an inaugural business plan outlining their fiscal plan, goals, and initiatives. The plan is presented as a guide for long-term improvement and encompasses 12 initiatives and 72 goals for HHSC and the Department of State Health Services (DSHS). According to HHSC, these are intended to improve operations, customer service, and workplace culture. However, it is the conviction of the Hogg Foundation for Mental Health that until issues of health disparities and racial inequities are made a priority and are addressed systemically, a healthy Texas will not be possible.

During the 2020-21 biennium, the Texas Legislature appropriated $78.5 billion to the HHS system. HHSC will receive the bulk of these funds, $76.8 billion, while $1.7 billion will go toward DSHS. The plan is a framework that prioritizes and guides HHS work beginning in fiscal year 2020. Additionally, it sets forth strategies for how agency divisions will accomplish each initiative’s respective goals.

According to HHS, the 12 initiatives in the plan were identified through feedback received from service recipients, legislators, providers, HHS team members, and partners over the preceding year. The plan is structured to work across HHS organizational lines in effort to address system-wide areas for improvement and transformational growth.

HHS has identified a framework of five commitments that serve as the foundation for the plan’s content. Each initiative, goal, measure, and deliverable focuses on one or more of the following:

- Efficiency, effectiveness, and process improvement

- Protecting vulnerable Texans

- Improving the health and well-being of Texans

- Integrity, transparency, and accountability

- Customer service and dynamic relationships

HHS outlines their 2020 initiatives as:

- Behavioral Health: Enhance Behavioral Health Care Outcomes

- Goal 1: Expand capacity for community-based behavioral health services

- Goal 2: Reduce negative health outcomes associated with opioid use

- Goal 3: Increase access to state psychiatric hospitals

- Goal 4: Transition to step-down options

- Disabilities: Increase Independence and Positive Outcomes for People with Disabilities

- Health & Safety: Improve Regulatory Processes that Protect Texans

- Medicaid Managed Care: Improve Quality and Strengthen Accountability

- Services & Supports: Connect People with Resources Effectively

- Strengthening Advocacy: Increase Long-Term Care Ombudsman Capacity

- Supplemental and Directed Payment Programs: Improve Accountability and Sustainability of Supplemental and Directed Payment Programs to Achieve Positive Outcomes

- Women & Children: Improve Health Outcomes for Women, Mothers and Children

- Team Texas HHS: Improve Our Culture, Recruitment and Retention

- Purchasing: Improve Procurement and Contracting Processes

- Quality Control: Identify and Mitigate HHS System Risks Through Effective Audit Activities

- Technology & Innovation: Leverage Technology and Process Improvement

The plan in its entirety can be found at https://hhs.texas.gov/sites/default/files/ documents/about-hhs/budget-planning/hhs-inaugural-business-plan.pdf

Long-standing systemic health and social inequities have put many people from racial and ethnic minority groups at increased risk of getting sick and dying from COVID-19. The term “racial and ethnic minority groups” includes people of color with a wide variety of backgrounds and experiences. But some experiences are common to many people within these groups, and social determinants of health have historically prevented them from having fair opportunities for economic, physical, and emotional health.

There is increasing evidence that some racial and ethnic minority groups are being disproportionately affected by COVID-19. Inequities in the social determinants of health, such as poverty and healthcare access, affecting these groups are interrelated and influence a wide range of health and quality-of-life outcomes and risks. To achieve health equity, barriers must be removed so that everyone has a fair opportunity to be as healthy as possible.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/ community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html

Office of Health Equity

Our society is not and has never been equitable. Recent events have led many of us to not shy away from questions that must be asked and responded to, in order for us to make substantial changes to address these inequities. There is not one single policy solution, but we must first look at where we are and how we arrived at this point in history. Black people have been disproportionately dying of COVID-19; nationwide Black people are dying at 2.371 times the rate of white people from the virus. What can we do to change these outcomes? Is structural racism a key social determinant of health? Is it a political determinant of health? How has the COVID pandemic underscored the historic racism in our healthcare system? How do structural inequities in our medical and health care systems impact the mental health and wellness of people of color? These are just a few of the questions awaiting answers. There are many more.

While there is a wealth of available information with evidence of significant inequities and disparities in our health (and other) systems, there are not many concrete policy and programmatic recommendations on how we move forward to fix the problems. The HHSC Center for Elimination of Disproportionality and Disparities/State Office for Minority Health was defunded through a rider during the 85th legislative session, which resulted in its elimination. Without a unit or office devoted to identifying the issues, collecting data, and researching solutions, the information needed to implement reforms is not available. Additionally, if no office exists that is specifically charged with responsibility and authority to address disparities and equity, the work will not get done with the same focus and attention.

An office addressing health disparities and health equity could be located in the Office of Mental Health Coordination at HHSC as that office coordinates efforts with at least 23 other state agencies. Other options for location of such an office should also be investigated. Example responsibilities a health equity office could be charged with include (but are not limited to):

- Collaborating across agencies to work to identify and eliminate systemic barriers to accessing healthcare services, including those that support mental well-being;

- Providing training and technical assistance to agencies and communities;

- Collecting and analyzing data to identify barriers and develop potential solutions;

- Providing programmatic assistance to help organizations implement changes to address inequities and disparities; and

- Disseminating information that promotes health equity.

The current environment calls for an invigorated focus within the state HHS system, including re-establishment of an office to address health equity and disparities in Texas.

The Intersection of COVID-19 and Mental Health and Wellness

As we write this section of our mental health guide, we are keenly aware of the myriad of consequences the COVID-19 pandemic has had on individuals, families, communities, and our country. We first want to express our heartfelt sadness and offer our sympathies to those who have first-hand experience of this vicious virus, especially those who have lost family members and friends to its attack. We know that your world has changed forever and the losses you have experienced are profound. It is not our intent in this guide to duplicate the multitude of information and data that is already available. The following information and data are intended to highlight the enormous impact of COVID-19 on our individual and collective mental health and well-being, both in the short-term and for years to come.

The increased need for mental health and substance use treatment and services will obviously stress our current systems already experiencing historical and continuing workforce shortages and access challenges. The 87th Legislature will face the intersection of a historically underfunded system with insufficient provider networks, as well as an increased need for mental health and substance use services and supports.

HHSC should be commended for initial actions taken early in the pandemic to enhance access to mental health services. In March 2020, a Mental Health Support Line was created to provide all Texans access to time-limited mental health support. Additionally, telemedicine and telehealth regulations were relaxed by both the federal and state governments to allow for remote provision and utilization of mental health and substance use services, including the allowance of services through audio-only telephone. These were impressive actions taken early that will hopefully continue long term.

It doesn’t seem that there is an aspect of American life that the COVID-19 pandemic hasn’t affected in some way. While this world crisis has brought out the best of humanity in many cases, the destruction and devastation it has caused is undeniable. The impact of the virus will be unfolding for years to come, including the impact on individual and collective community mental health and well-being.

The pandemic will result in a behavioral health crisis with a historic rise in mental health issues and substance use disorder.

Integral Care, Transparencies, Minority Mental Health Disparities & COVID-19, July 2020 https://integralcare.org/en/ transparencies0720/

MENTAL HEALTH CONSEQUENCES

Evidence of increased need for mental health and substance use services since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic has already been documented. A recent study published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report and highlighted on the CDC website (https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6932a1.htm) offers insight into the mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on communities.

The study indicated that:

Adults in the U.S. are experiencing considerably elevated adverse mental health conditions associated with COVID-19. Younger adults, racial/ethnic minorities, essential workers and unpaid adult caregivers reported having experienced disproportionately worse mental health outcomes, increased substance use, and elevated suicidal ideation.

Some notable indicators revealed through the study include:

- 40.9 percent of American adults reported having at least one adverse mental/ behavioral health consequence resulting from the pandemic. In most pre-COVID analyses, that number was typically reported as being 20 to 25 percent.

- The primary mental health/substance use problems identified by survey participants in the study included:

- High levels of anxiety and/or depression (30.9 percent)

- Significant trauma (26.3 percent)

- Increased substance use (13.3 percent)

- Consideration of suicide (10.7 percent)

POPULATION IMPACT

The study also highlights the mental health impact on certain populations, including:

- 74.9 percent of young adults age 18-24

- 51.9 percent of adults age 25-44

- 52.1 percent of Hispanics

- 54 percent of essential workers

- 61.6 percent of unpaid caregivers

- 66.2 percent of individuals with less than a high school diploma.

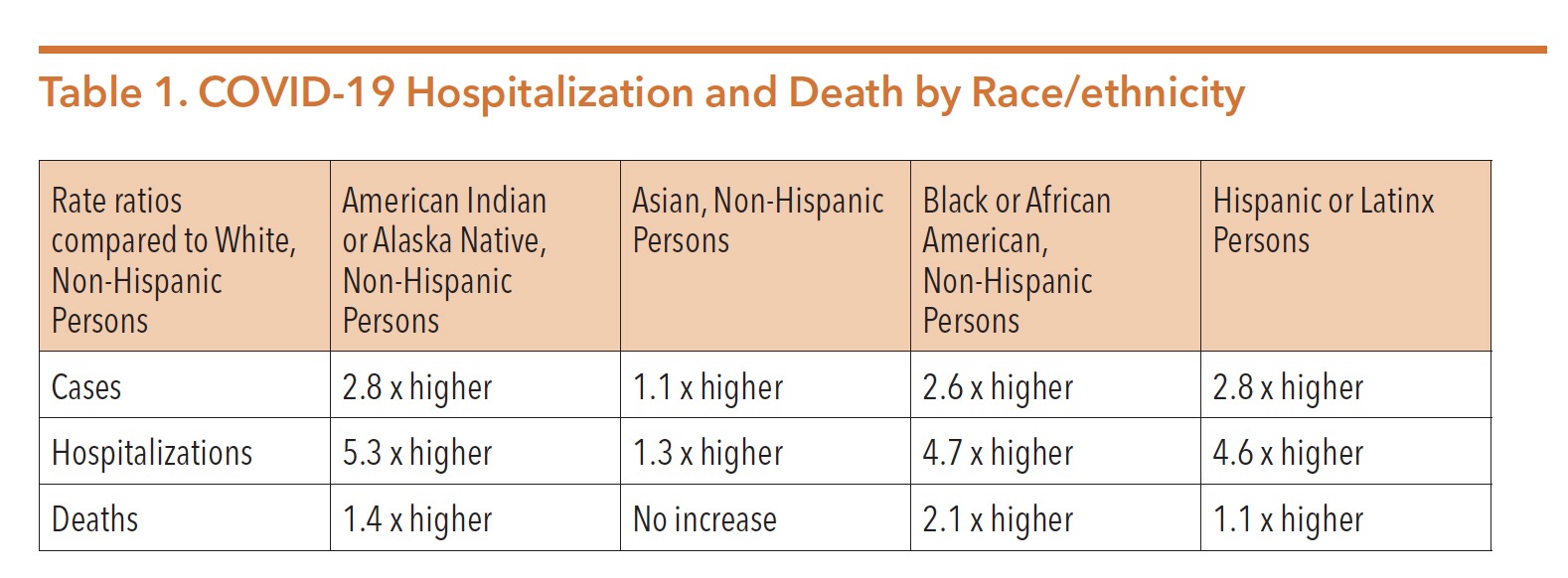

As has been shown in many parts of the country, the impact of COVID-19 is often worse for people of color with less access to resources and support due to socioeconomic status, less access to health care, and increased exposure due to occupations not conducive to working from home. The table below provides a representation of cases, hospitalizations, and death rates by race/ethnicity.

Source: CDC Website, Updated 8/18/2020; https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/ hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html

Source: CDC Website, Updated 8/18/2020; https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/ hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html

The consequences of COVID-19 on people of color provides further evidence of the damage caused by health disparities and inequities. The pandemic has provided stark evidence of the need for Texas to create an Office of Health Equity to build awareness, provide education, develop strategies, and assist with implementing corrective measures to mitigate the impact and eliminate the causes of disparities based on race, ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, disability, and more.

NONPROFIT FALLOUT

Adding to the complexity of addressing the mental health needs of Texans during the pandemic is the reality that many nonprofit organizations that often support community well-being are also struggling. A recent survey conducted by the United Way of Texas and the OneStar Foundation provided insight into the impact of the pandemic on 501(c)(3) organizations in Texas. The survey and others were included in the development of a report The Impact of COVID-19 on Texas Nonprofit Organizations, released in August 2020 as part of the Built for Texas initiative. Some key findings show:

- 70 percent of organizations changed operations or services so that they could more directly support the COVID-19 response;

- 60 percent of organizations are providing services that directly support the health or basic needs of those affected by the COVID-19 pandemic;

- 18 percent are providing services that mitigate the spread of COVID-19;

- 69 percent experienced disruption of services to clients and communities;

- 62 percent experienced increased demand for services/support from clients and communities;

- 40 percent experienced increased or sustained staff and volunteer absences;

- 24 percent instituted staff lay-offs or furloughs;

- 82 percent cancelled programs or events due to reduced revenue; and

- 70 percent experienced budgetary implication related to strains on the economy.

The reduction in community and individual support directly impacts current and future mental health and wellness in our communities. The full report can be viewed at https://txnonprofits.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Impact-of-COVID19-on- Texas-Nonprofit-Orgs_August-2020.pdf.

ONGOING CHALLENGES

Additional vital considerations must be considered when policy makers, legislators and stakeholders analyze future needs and the impact on mental health, including:

- Impact of ongoing financial stressors and unemployment;

- Challenges families face in managing children, school options, employment, food insecurity, potential eviction, loss of employment, isolation, and lack of emotional support;

- Impact to older Texans in nursing and assisted living facilities, as well as those living alone with little external contact and minimal support;

- Loss of health insurance and the inability to obtain health care when needed;

- Over-representation of people of color in case counts, hospitalizations, and deaths; and

- Potential loss of telemedicine and telehealth flexibilities made possible during COVID-19 and impacts on people using those services for mental health and substance use treatment.

COVID-19 presents many challenges to Texas and the nation. Mental health and substance use supports, services, and treatment will be needed by more Texans in the months and years to come as a result of the pandemic fall-out.

The Intersection of Racism and Mental Health

Institutional racism, disparities, and inequities exist in Texas healthcare systems. This causes and exacerbates already existing trauma, anxiety, depression, PTSD, substance use, and other mental health conditions. Communities of color face discrimination that prevent them from accessing health care, including mental health and substance use treatment, services, and supports. The global COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent economic downturn has disproportionately impacted communities of color and heightened those disparities. Additionally, the murders and/or shootings of George Floyd, Jacob Blake, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and numerous other Black Americans in 2020 has sparked global unrest against racism and police brutality. Discrimination and violence against communities of color has led to local and state leaders across the country declaring racism a public health crisis. Not only is racism a public health crisis, but it is also a public mental health crisis.

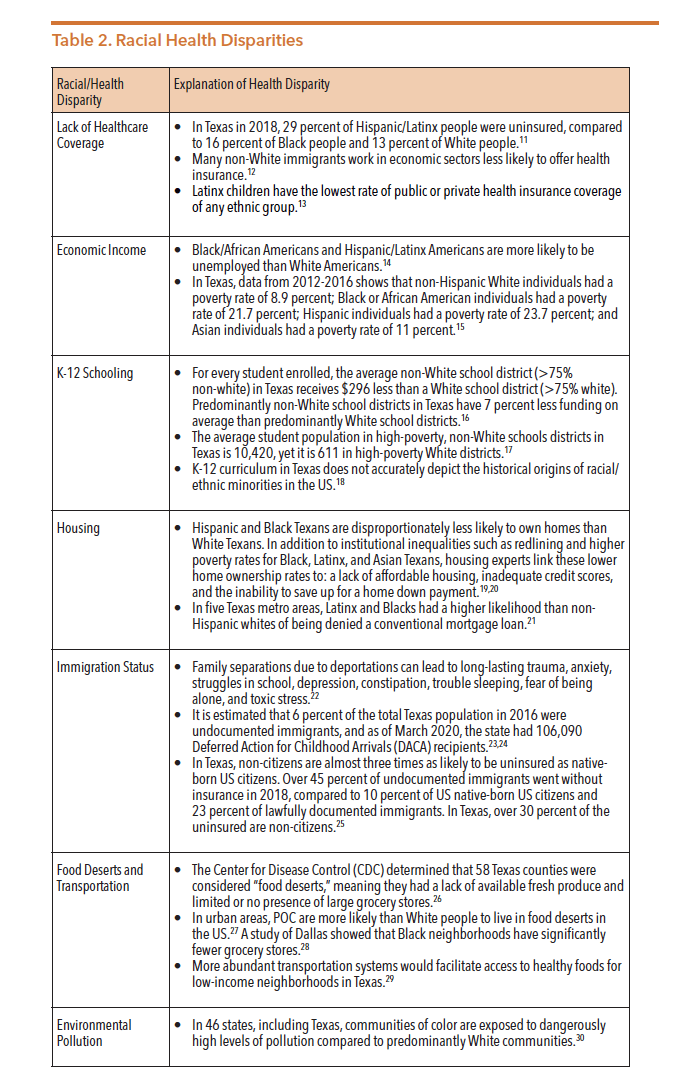

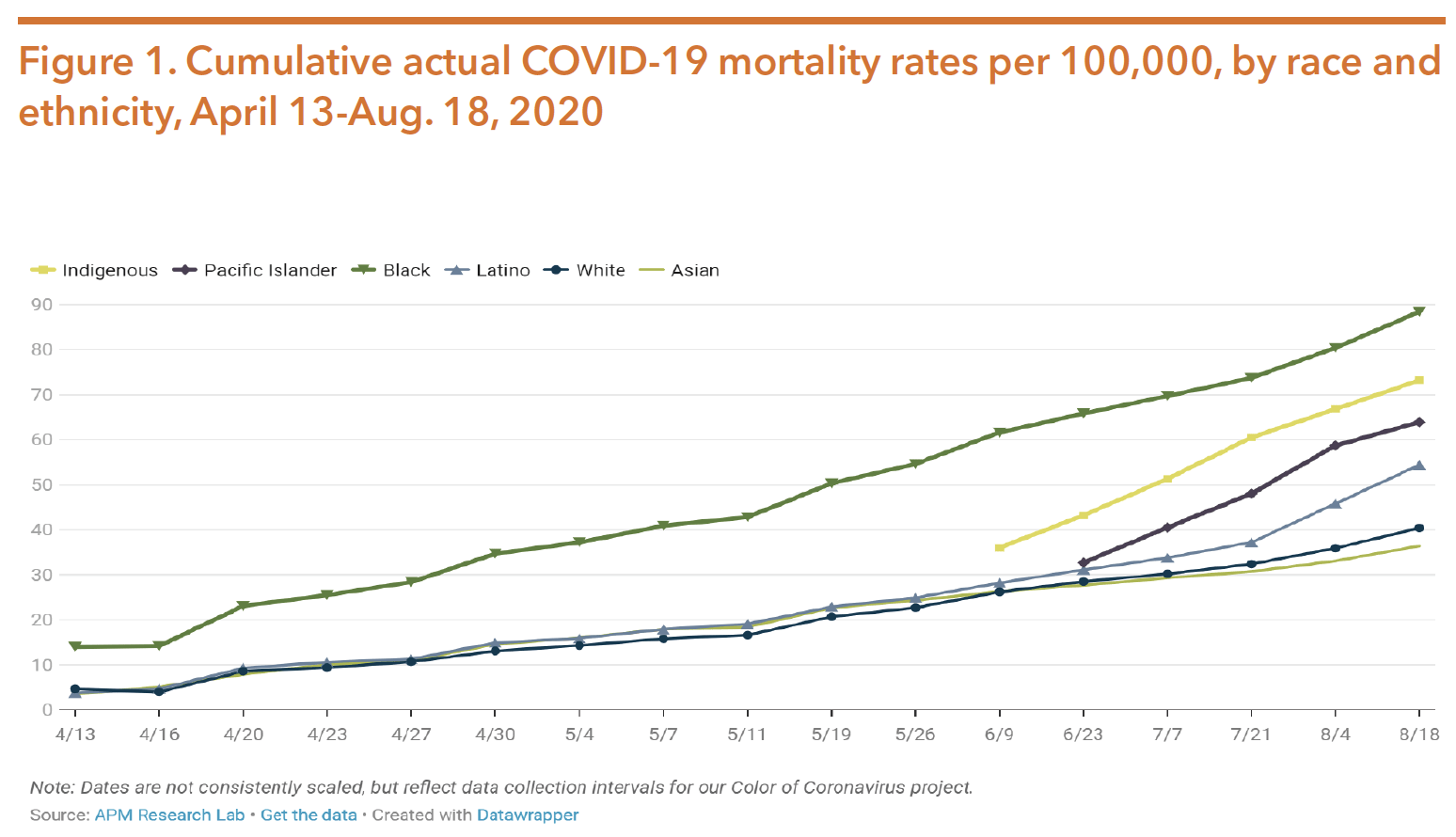

HEALTH DISPARITIES

In order to understand how racism impacts mental health, it is essential to break down how institutional racism continues to oppress communities of color. Table 2 below lists a fraction of the numerous institutional barriers that can reduce access to services and increase severity of mental health conditions for people of color (POC):

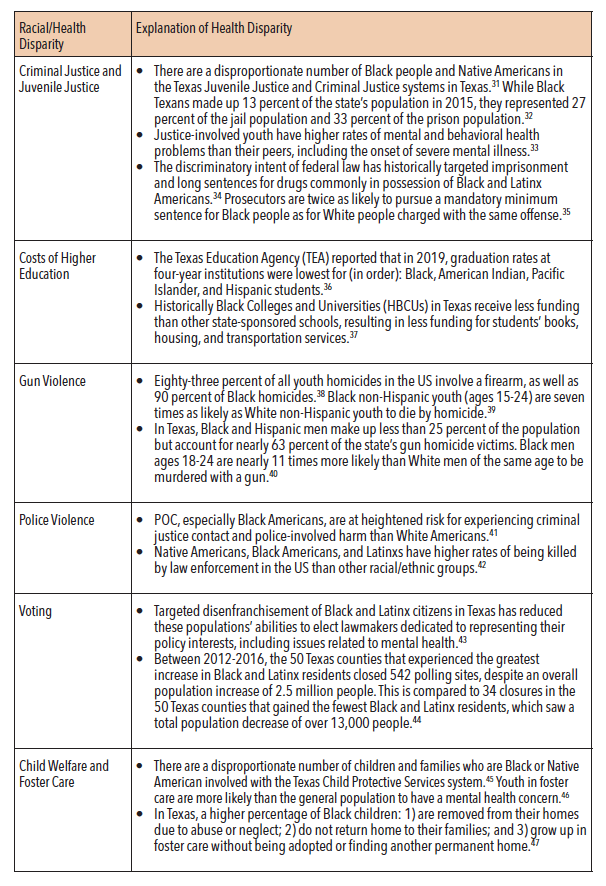

COVID-19’S DISPROPORTIONATE IMPACT

Due to racial health disparities described throughout this chapter, the COVID- 19 pandemic has disproportionately affected POC. Research indicates that the pandemic is expected to increase rates of mental health and substance use disorders, as well as deaths associated with suicide, overdose, and violence. The following data comes from the APM Research Lab; at the time of writing, Texas and 47 other states had not yet publicly released COVID-19 mortality data by race and ethnicity. Of the more than 170,000 COVID-19 deaths as of August 18, 2020, race/ethnicity data was missing for about 5 percent of deaths.

As of August 18, 2020, Black Americans had the highest death toll from the virus at 88.4 deaths per 100,000 people, which is over two times as high as the mortality rate for White and Asian Americans. Figure 1 shows how Black COVID-19-related deaths were followed by Indigenous Americans at 73.2, Pacific Islander Americans at 63.9, Latinx Americans at 54.4, White Americans at 40.4, and Asian Americans at 36.4 per 100,000 people.

Source: COVID-19 deaths analyzed by race and ethnicity. (2020, August 19). Retrieved from https://www.apmresearchlab. org/covid/deaths-by-race

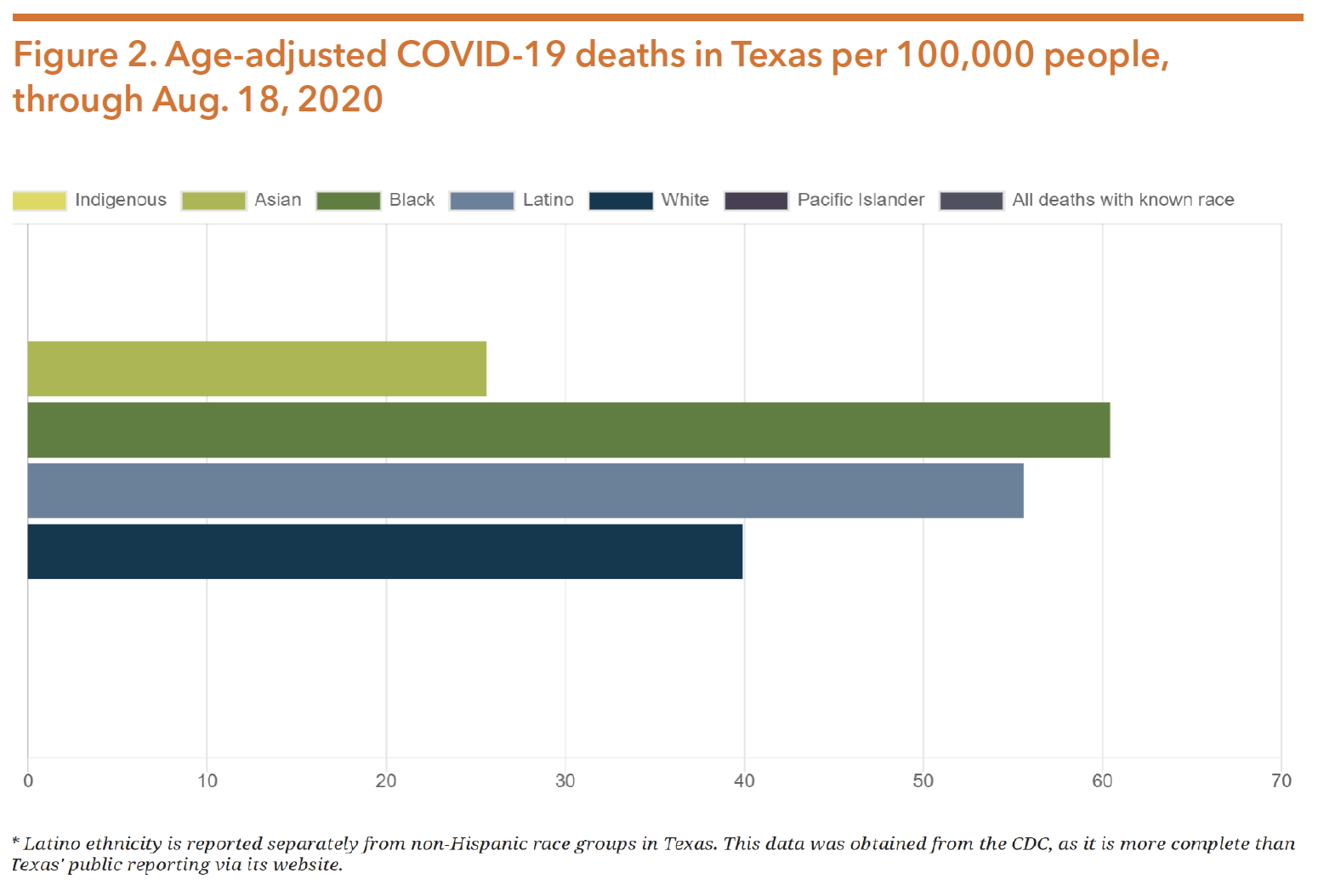

As of August 18, 2020, Black Americans had experienced 22.1 percent of all COVID- 19 deaths, despite representing only 12.4 percent of the population. Indigenous Americans had experienced 2.1 percent of all deaths (in 30 states reporting one or more deaths), despite representing about one percent of the population in those states. White Americans had experienced 50.6 percent of all deaths, but represented 62.2 percent of the population. Adjusting for age differences in the race groups widens these gaps even further compared to Whites, with COVID-19 mortality rates being: 3.6 times higher for Blacks, 3.4 times higher for Indigenous people, 3.2 times higher for Latinxs, 3.0 times higher for Pacific Islanders, and 1.3 times higher for Asians. Age-adjusted data reveals how the mortality rate for Latinxs increases more than any other group when compared to the actual rate. This shows that Latinxs are dying from the virus at a higher rate than expected given the group’s relative youthfulness. Figure 2 below shows age-adjusted COVID-19 deaths in Texas.

Source: COVID-19 deaths analyzed by race and ethnicity. (2020, August 19). Retrieved from https://www.apmresearchlab. org/covid/deaths-by-race

Given that stress, depression, irritability, fear, confusion, frustration, boredom, stigma, anxiety disorders, and other emotions are prevalent during pandemics, the mental wellness of POC is at particular risk because of existing racial health disparities.

RACISM CAUSES TRAUMA

Racism causes trauma, making it an inherent mental health issue. Racial trauma accumulates throughout a person’s life, leading to activation of stress responses and hormonal adaptations. This increases the risk of non-communicable diseases and biological aging. Racial trauma is also transmitted intergenerationally and affects the offspring of those initially affected through complex biopsychosocial pathways. Lower rates of access to mental health services, as well as lower usage of these services for those who do have access, make the burden of trauma incredibly harmful to communities of color. The below subsections breakdown a few of the many issues that disproportionately reinforce racial trauma.

GUN VIOLENCE

Gun violence is at the root of cyclical trauma in communities of color. Black non- Hispanic youth (ages 15-24) are seven times as likely as White non-Hispanic youth to die by homicide, and 83 percent of youth homicides involve a firearm (up to 90 percent for Black homicide victims). Individuals who have survived or witnessed gun violence in their communities have constant feelings of danger and vigilance that lead to many being fearful to leave their homes. This can be burdensome to their mental wellness, resulting in anxiety, depression, PTSD, constant agitation, sleep disturbances, hopelessness, and other mental health conditions. Experts indicate that those routinely exposed to gun violence can behave similarly to war veterans, as they must learn to interpret potential threats to survive. This consequently leads to further psychosocial, medical, and mental health issues.

Due to the repeated high-profile mass shootings in the US, there are also common sentiments of fear from Americans (especially POC) who are not survivors or witnesses of gun violence. According to an August 2019 study by the American Psychological Association:

- Nearly 80 percent of adults said they experienced stress as a result of the possibility of a mass shooting;

- About one-third of adults said fear of a mass shooting prevents them from going to certain places or events; and

- One-fourth had changed their livelihood because of fear of a mass shooting.

While 15 percent of non-Hispanic adults say they experience stress often or constantly related to the possibility of a mass shooting, 32 percent of Hispanic adults say the same. Hispanic (44 percent) and Black (43 percent) adults are also more likely than White non-Hispanic (30 percent) adults to say they do not know how to cope with stress caused by mass shootings. Additionally, 60 percent of Black and 50 percent of Hispanic adults feel that they or someone they know will be a victim of a mass shooting, compared to 41 percent of White adults.

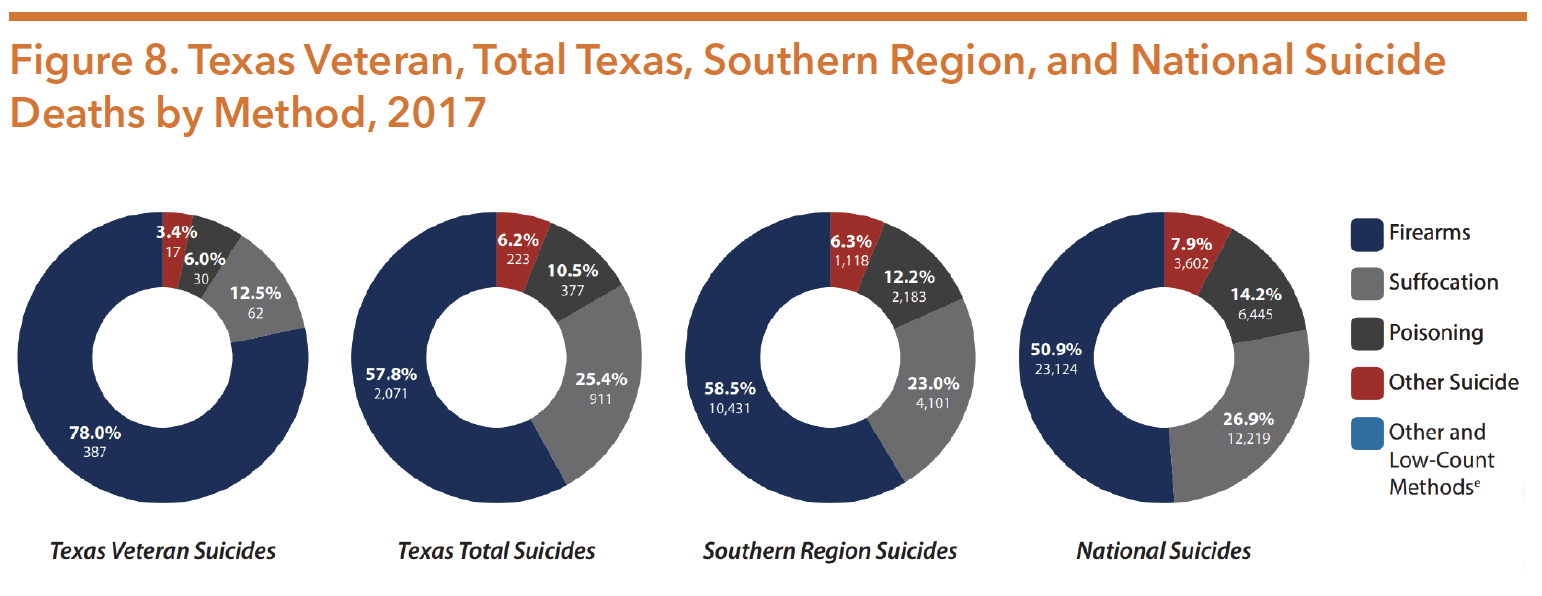

Firearms are also the most lethal method of suicide. While the average suicide attempt has an 8.5 percent death rate, those with firearms have an 89.6 percent mortality rate. According to 2017 CDC data, suicide was the third leading cause of death for Black youth ages 1-19, illustrating how mixing suicidology and access to lethal means for youth experiencing racial trauma can lead to increased mortality.

Trauma caused by gun violence is costly on the national and Texas healthcare systems. A study that focused on pediatric firearm injuries found that:

- The median cost per firearm-related hospitalization was $10,159, a figure that does not take into account long-term mental health supports and services.

- About half of children hospitalized from a firearm-related injury were discharged with a disability, including cognitive and behavioral conditions.

- Of the youth included in this study, 44 percent of firearm hospitalizations involved Black individuals, 19 percent Hispanic youth, and 16 percent White youth.

POLICE VIOLENCE

What’s often left out of the discussion on gun violence is the disproportionate impact that police shootings have on communities of color. From 2010-2015, police officers shot at suspects in Texas at least 656 times in 36 of the state’s largest cities. People with untreated psychiatric or mental health conditions are also more like to be killed by law enforcement, and due to Texas’s racial disparities in access and use of mental health services, this directly impacts POC.

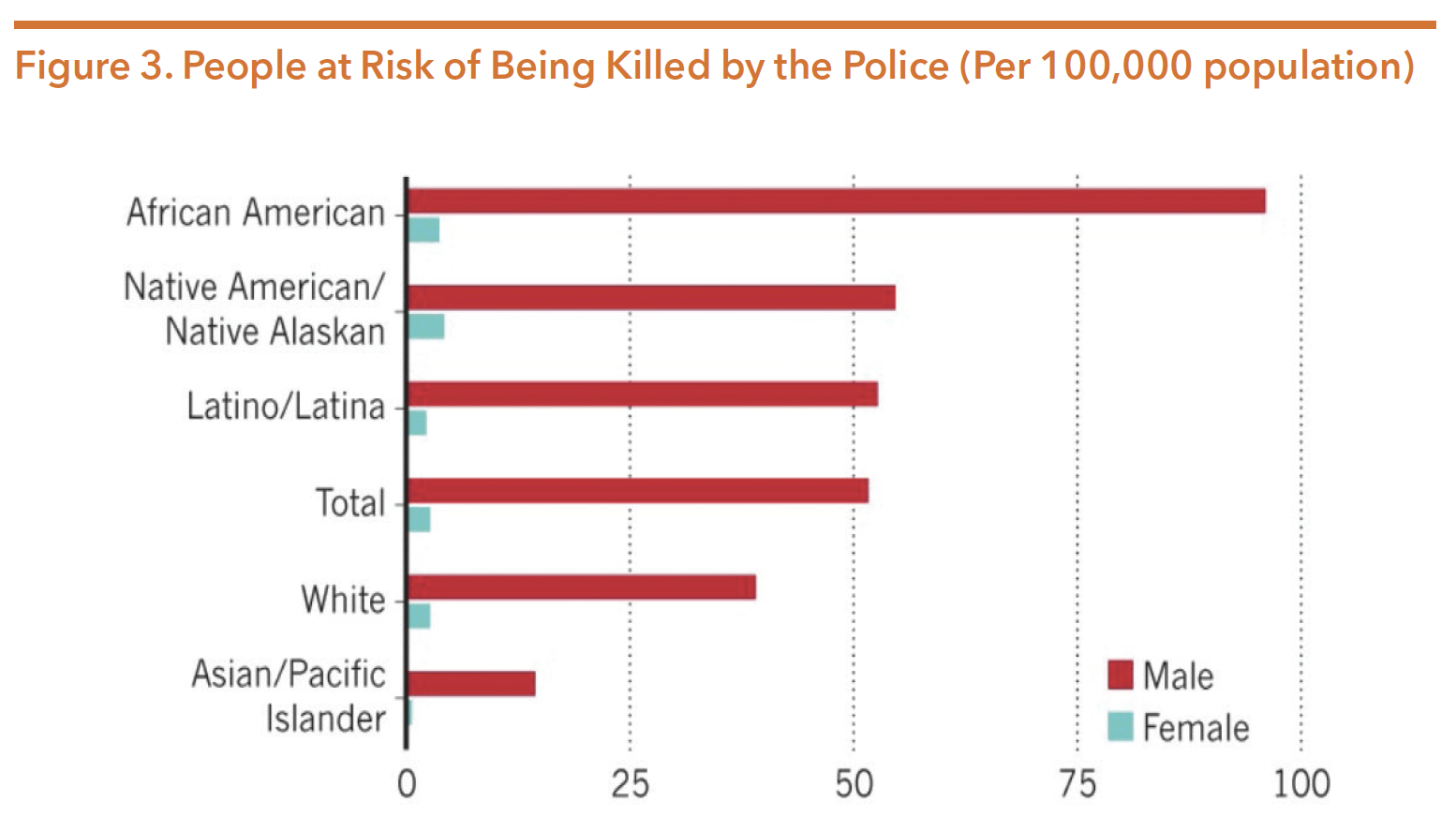

According to 1999-2015 CDC data, Native Americans, Black Americans, and Latinx Americans have higher rates of being killed by law enforcement than other racial/ ethnic groups. Figure 3 below illustrates how Black males are disproportionately at a higher risk of being killed by police in the US, a rate twice as high as White Americans. Studies show that police officers tend to associate Black people with threat, and have stronger associations between Black Americans and weapons than other ethnicities. Additionally, police officers are more likely to view Black youth as having higher pain tolerance than other groups of people, a bias often used to justify forms of police brutality. The prevalence of racial bias in policing puts POC at significantly higher risk of experiencing trauma because of interactions with law enforcement and the criminal justice system.

Source: Peeples, L. (2019, September 04). What the data say about police shootings. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/ articles/d41586-019-02601-9

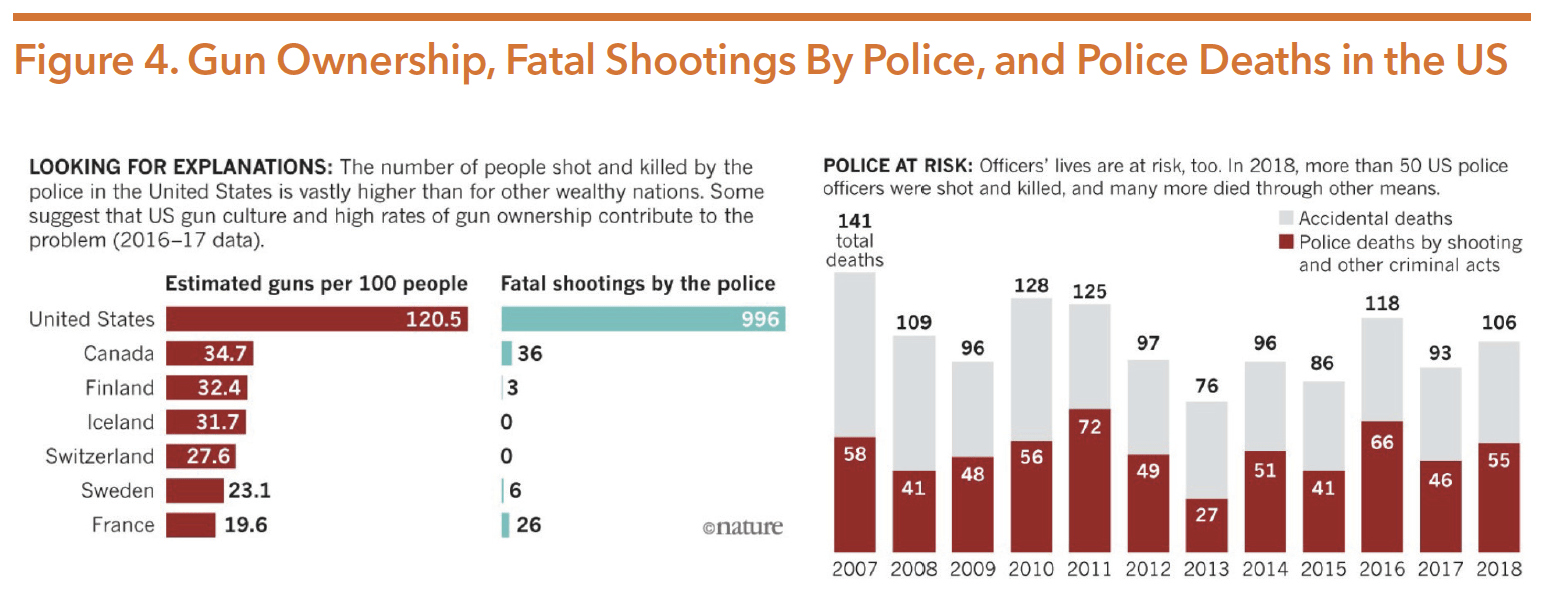

While racial bias exists in every nation, including in law enforcement bodies, the US has disproportionately high rates of police killings that consequently plague communities of color with loss and trauma. Fear that an individual was in possession of a weapon, and thus that an officer feared for their life, is often cited as a reason by law enforcement bodies for a police shooting. The racial bias previously described, in combination with high levels of gun ownership in the US, can in part explain this trend. This is because most other countries’ law enforcement bodies do not deal with the constant threats of gun violence to the same extent as in the US. There are more firearms in the US than there are people, and gun ownership rates are nearly two times as high as the next highest country. Texas itself has the most registered firearms in circulation of all 50 states, and had the second most police killings from 2013- 2019. The disproportionate impact of police killings on POC reinforces trauma in communities of color. Figure 4 below shows how shootings by law enforcement in the US are over three times higher than in other developed nations, and how these fatal shootings correlate with trends of high gun ownership in the US.

Source: Peeples, L. (2019, September 04). What the data say about police shootings. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/ articles/d41586-019-02601-9

Police officers themselves often face mental health conditions that are a result of dangers associated with the job such as police-involved shootings. Figure 4 above shows how, in 2018, 55 law enforcement officers were shot and killed—an increase from 46 in 2017. A survey of police who were involved in shootings reported they illustrated trauma-response symptoms such as: heightened sense of danger, anxiety, flashbacks, emotional withdrawal, sleep difficulties, alienation, depression, problems with authority, nightmares, family problems, guilt, alcohol/drug abuse, sexual difficulties, and suicidal thoughts. These symptoms highlight how racial targeting by law enforcement and the prevalence of weapons in the US creates violence and trauma, which not only affects mental wellness of communities of color, but those of police officers themselves.

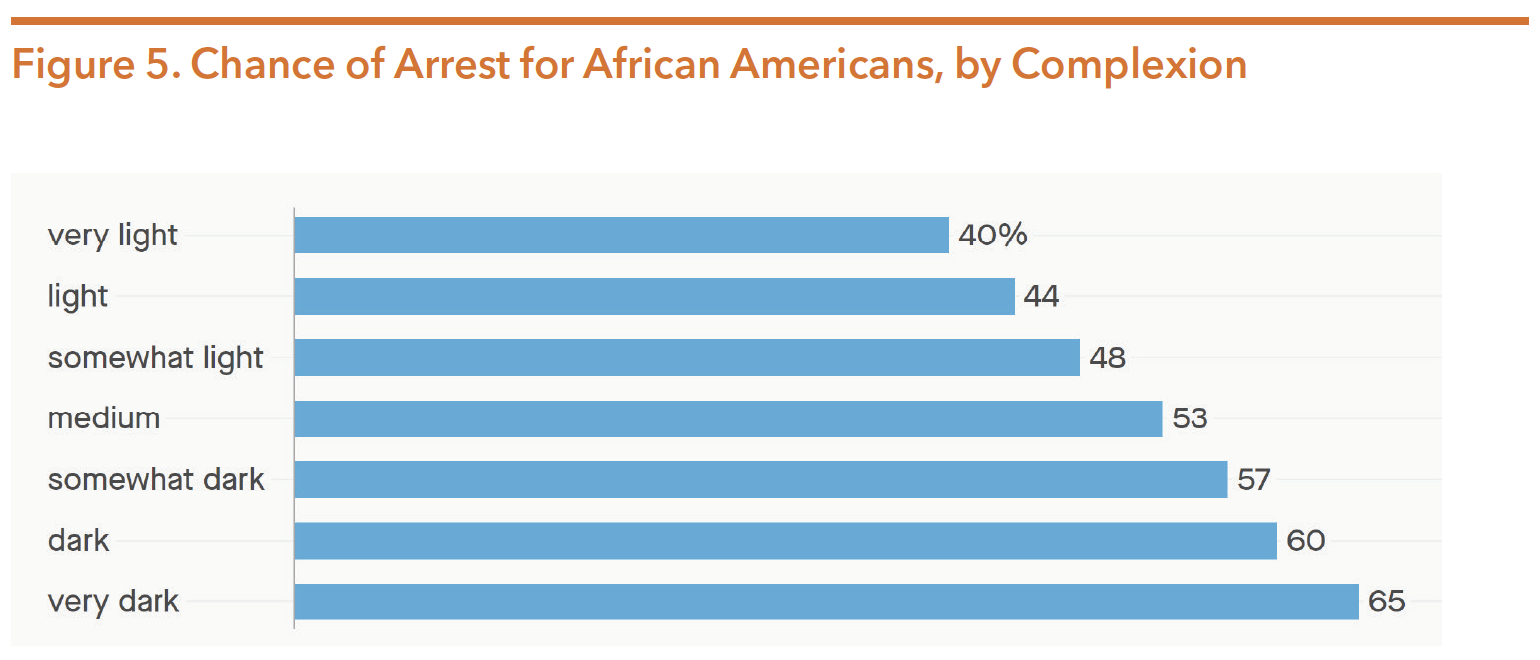

COLORISM

Colorism refers to “prejudice or discrimination, especially within a racial or ethnic group, favoring people with lighter skin over those with darker skin.” It is difficult to quantify the affect colorism plays in someone’s mental health, largely because of the subjectivity with how someone might identify or is perceived. A 2015 study indicated that Asian Americans have been racialized within the Black/White binary, a dichotomy that has affected how members of this community process internal self-identification based on color and skin tone. Another study examined survey results of Black Americans’ complexion from 2001-2003. As is shown in Figure 5, the darker someone’s skin tone (determined by interviewers who administered the survey), the more likely they were to be arrested. The author of that study, after revisiting it 15 years later, found that, “after accounting for differences like gender and level of education…(all) African Americans have an overall 36% chance of going to jail at some point in their lifetimes. Dark-skinned African Americans, meanwhile, have a near 66% chance.” This form of colorism is significant to the mental health conversation because frequency of trauma exposure is associated with criminal justice involvement.

Source: Merelli, A. (2019, October 15). Chance of arrest for African Americans, by complexion. Retrieved from https://theatlas. com/charts/jSkmm0svz

Additional studies have shown that:

- Black people and Latinxs who are deemed to have lighter skin tones are also significantly more likely to be seen as intelligent by White people;

- Lighter-skinned Black men with bachelor’s degrees had a distinct advantage in job application processes over darker-skinned Black men who had MBAs;

- Lighter-skinned Black women in North Carolina received lighter prison sentences than their darker peers; and

- Black Americans with more education are remembered as being lighter than they actually are.

All of these socialized ways of thinking could affect POCs’ life trajectories. From the opportunities one might not receive based on skin tone to the trauma one could be exposed to because of how they are treated based on their complexion, it is important to acknowledge the existence of colorism and the role that it plays in deepening racial biases. Colorism thus plays a direct role in reinforcing trauma and other forms of mental health conditions.

EXHAUSTION

An often-overlooked cause of racial trauma is the toll of exhaustion on POC. Exhaustion can be a result of a variety of different factors, including but not limited to:

- Receiving microaggressions;

- Viewing continuous streams of violence against POC or other traumatic events involving POC (i.e., footage circulating of a cop’s knee on George Floyd’s neck);

- Having to explain white privilege and colorism;

- Having to educate others on the history of one’s culture, ethnicity, background, and values;

- Appropriation of one’s culture;

- Tokenization;

- Fetishization;

- Lack of representation in positions of power and influence; and

- Intersectionality of racism and other forms of discrimination (gender, sexual orientation, disability status, religion, etc.).

These issues, which constantly affect POC daily, perpetuate exhaustion and can negatively impact mental wellness. Dealing with all of the aforementioned challenges consequently can lead to significant physical and mental health conditions such as PTSD.

IMMIGRATION/CITIZENSHIP STATUS

Research shows that fear of deportation and family separation can present significant harm to a child’s mental health. They act as toxic stressors, which can permanently change the biology of a child’s brain. In Texas, 64.8 percent of individuals born outside of the US are Latinx, 20 percent are Asian, and 5.8 percent are Black, according to the Migration Policy Institute. About 51 percent of Texas immigrants are from Mexico.

A 2018 report studied respondents in the Rio Grande Valley, where about 80 percent of people are of Mexican descent. Selected respondents were directly impacted by changing immigration policies and anti-immigrant rhetoric, and 20 percent said their child experienced post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following a parent’s deportation. This was compared to 5 percent for all children in the US. Symptoms ranged from increased anxiety, struggles in school, depression, constipation, trouble sleeping, and fear of being alone. One in four children of undocumented parents in the Rio Grande Valley experienced stress because of a parent’s immigration status, compared to one in ten children with parents of a legally protected status. Immigration related stressors also impact school success, as 41 percent of undocumented respondents had children with symptoms of school avoidance anxiety. This rate was 30 percent for those with protected status, and 20 percent for parents with citizenship. Additionally, 22 percent of undocumented parents reported their child had trouble keeping up their grades, compared to just 4 percent of protected status parents. The survey also found that adult mental and physical health in the Rio Grande Valley is impacted by the threat of detention and deportation for those with undocumented status.

Undocumented transgender individuals also face disparities that lead to trauma and mental health conditions. See the Discrimination and Violence Against the LGBTQIA+ Community section below for more information on the trauma faced by undocumented transgender people.

DISCRIMINATION AND VIOLENCE AGAINST THE LGBTQIA+ COMMUNITY

Individuals who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex or asexual (LGBTQIA) are disproportionately exposed to stressors that cause depression, substance use, and increased risk of suicide. Survey results showed that 39 percent of transgender respondents experienced serious psychological distress in the month prior, compared with 5 percent of the US population. In addition, 40 percent had attempted suicide, a figure nearly nine times higher than the US attempted suicide rate of 4.6 percent.

When combined with racism, POC in the LGBTQIA+ community often face additional mental health hurdles. The year 2020 has seen increased levels of violence against primarily Black transgender women. In just the first 7 months of 2020, there were more transgender people murdered (28) than in all of 2019 (26). Of the 28 individuals killed, 23 were trans women, four were trans men, one was non-binary, and a majority were Black or Latinx.

According to a survey by the National Center for Transgender Equality of over 28,000 individuals, transgender people face high levels of stigma and discrimination that negatively impact their mental health. Forty-seven percent of Black respondents and 30 percent of Latinx respondents reported being denied equal treatment, verbally harassed, and/or physically attacked in the previous year because of being transgender. Black transgender women were more likely to be physically attacked in the previous year because of being transgender, in comparison to non-binary people and transgender men. About 24 percent of transgender undocumented respondents had been physically attacked in the prior year. Half of undocumented respondents also experienced homelessness in their lifetime, and 68 percent had faced intimate partner violence.

LACK OF USE OF TREATMENTS AND SERVICES

In addition to health disparities and structural inequalities that limit POC’s access to mental healthcare services, those who do have access are still less likely to receive treatment than White Americans. A 2014 study indicated that African Americans are more likely than White Americans to terminate treatment prematurely. Of all adults with a diagnosis-based need for mental health or substance abuse care, only 22.4 percent of Latinxs and 25 percent of Black people received treatment, compared to 37.6 percent of Whites. Overall spending for Blacks and Latinxs on outpatient mental health care was about 60 percent and 75 percent of White rates. The study states that efforts to eliminate these disparities have been unsuccessful in both primary care and specialty psychiatric services. Black and Latinx children also have the highest rates of unmet need for mental health services.

There are several reasons POC are less likely to use clinical mental healthcare services. These include: high uninsured rates, financial and healthcare restraints caused by systemic racial oppression, long-held stigmas against seeking help within the community, preferred reliance on faith-based practices, and the inability of some healthcare providers to establish themselves as credible and reliable sources of support. The history of discrimination in healthcare, especially against Black women, has led many POC to hold a fundamental mistrust of some healthcare providers and services. In order to reduce disparities and treat mental health conditions within communities of color in Texas, policies should not only expand access to care, but also incentivize these services to be utilized by providing better outreach and education. Policies should also leverage the usage of spirituality and faith-based practices by many POC to better mental wellness, hire and train a more diverse mental health workforce, and work to increase the quality of mental health care.

Mental Health and Substance Use Workforce Shortage

Mental health and substance use workforce challenges are not new, and they continue to exacerbate the shortage of available treatment options. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic is projected to increase rates of mental health and substance use conditions, thereby significantly increasing the demand for mental health services and amplifying the workforce shortage.

Meeting the needs of Texans with mental health and substance use conditions requires a robust and diverse behavioral health workforce. Texas faces critical shortages for many licensed mental health professionals, including: psychiatrists, psychologists, professional counselors, clinical social workers, marriage and family counselors, and advanced practice psychiatric nurses. As of June 30, 2020, an analysis by the US Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of mental health professional shortages showed that Texas had only met about 36 percent of the state’s need. In 2019, 173 Texas counties did not have a single licensed psychiatrist, which left over 2.7 million Texans living in counties without access to a psychiatrist. An additional 24 counties only had one psychiatrist, serving over 970,000 individuals. The majority of mental health services are provided by mental health professionals other than psychiatrists, including: primary care physicians, nurses, social workers, physician’s assistants, certified peer specialists and certified recovery coaches, family partners, community health workers, marriage and family therapists, and counselors. In many parts of Texas, significant shortages of all mental health providers also exist. It is important to note that primary care providers deliver more than half of all mental health services for common mental health conditions, like anxiety and depression. A 2018 report from Texas’s Health Professions Resource Center estimated that, due to the national shortage of mental healthcare professionals, Texas is unlikely to meet staffing needs by way of recruiting practitioners from other states. The shortage was expected to worsen as the workforce ages prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Various state and federal legislative initiatives, agency reports, and advocacy efforts have offered recommendations for addressing workforce challenges across the various mental health disciplines. Only a few of these recommendations and strategies have been funded and implemented.

Recognizing the need to proactively address the critical behavioral health workforce shortage in Texas, HHSC created the Behavioral Health Workforce Workgroup in 2019. The workgroup worked for over a year to identify recommendations and strategies included in previous studies and reports and develop a “next steps” workplan for HHSC and the legislature to use when considering future actions needed to ensure an adequate and viable behavioral health workforce for Texas. This report lays out a comprehensive set of recommendations that should be used as a blueprint for action. The workplan and recommended next steps are divided into seven categories including:

- Retention, Recruitment, and Incentives

- High School Pipeline

- Higher Education

- Licensing and Regulation

- Innovative System Improvements

- Medicaid Administration

- Other

Some of the gaps and barriers contributing to the current mental health workforce shortage include:

- Unwillingness of mental health providers to accept patients with Medicaid;

- Inequitable distribution across the state, primarily affecting rural areas;

- An aging workforce;

- Linguistic and cultural barriers – the workforce does not reflect the culture and ethnicity of the state’s population;

- Inadequate and inequitable reimbursement practices. Reimbursement rates are too low and the rating structure allows for different rates for the same services depending on the provider type;

- Limited internship sites and the cost of supervision for psychology, social work, and counseling; and

- Lack of high-quality broadband/internet access in rural communities that is needed to access telehealth/telemedicine services. The COVID-19 pandemic has further amplified the need for telehealth and telemedicine services and policy innovations.

During the 86th session, the Texas legislature took some steps to improve the mental health workforce capacity. The shortage continues, however, and much more work and funding is needed to make lasting changes. The following is a summary of workforce-related legislation passed during the 86th legislative session:

- HB 1 allocates $13,460,000 in general revenue for FY 2020/2021 to the University of Texas at Tyler. The funds are meant to support mental health workforce training programs in underserved areas including, but not limited to, Rusk State Hospital and Terrell State Hospital.

- HB 1065 (Ashby/Kolkhorst) creates a rural resident physician grant program to encourage the creation of new graduate medical education positions in rural and non-metropolitan areas. The intent is to place particular emphasis on the creation of rural training tracks.

- SB 11 (Taylor/Bonnen) includes provisions for increasing opportunities for integrated health care for children. It also provides funding for psychiatric residencies.

- HB 1501 (Nevarez/Nichols) establishes the Texas Behavioral Health Executive Council (TBHEC) by consolidating the Texas State Board of Examiners of Marriage and Family Therapists, Texas State Board of Examiners of Professional Counselors, and Texas State Board of Social Worker Examiners with the Texas State Board of Examiners of Psychologists. Authority to administer examinations, issue licenses, set fees, and take disciplinary action for marriage and family therapists, licensed professional counselors, social workers, and psychologists was transferred from each individual health board to TBHEC. The Psychology Interjurisdictional Compact was established to regulate telepsychology and temporary, in person practice of psychology across state boundaries.

Funding for the Loan Repayment Program for Mental Health Professionals, initially established by SB 239 (84th, Schwertner/Zerwas), was continued by the 86th Legislature. As of September 2020, it was reported that there are insufficient funds to enroll new participants during the 2020-2021 fiscal year. This program offers up to five years of student loan repayment assistance to mental health providers working in Mental Health Professional Shortage Areas, and is run by the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board.

Peer Support Services in Texas

Peer support services are a critical component of the Texas mental health and substance use workforce. The Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) should be commended for their recognition and validation of peer support services and their continued efforts to improve, expand, and enhance these services to support recovery.

Peer supports are provided by individuals with lived experience of mental health and/or substance use conditions who are trained and certified. These individuals assist others achieve long-term recovery. Peer specialists offer emotional support, share knowledge, teach skills, provide practical assistance, and connect people with resources, opportunities and communities of support.

While peer services have existed in Texas for a number of years, the Texas Legislature and HHSC continue to take steps to increase access to these valuable services. Major recent advancements include:

- Passage of HB 1486 (85th, Price/Schwertner) directing HHSC to define peer services, identify criteria for certification and supervision, and provide Medicaid reimbursement;

- Establishment of rules relating to peer training, certification, and supervision requirements, and the defining of the scope of services a peer specialist may provide. HHSC has also adopted rules that distinguish peer services from other services that a person must hold a license to provide;

- Creation of the director of peer services position at HHSC;

- Development of the Peer Services Programs, Planning, and Policy Unit at HHSC staffed by individuals with lived experience of mental health and/or substance use conditions;

- Planning for and development of the Leadership Fellows Academy in partnership with the Hogg Foundation for Mental Health and the University of North Carolina. The goal of this project is to develop operational capacity of peer-operated service organizations.

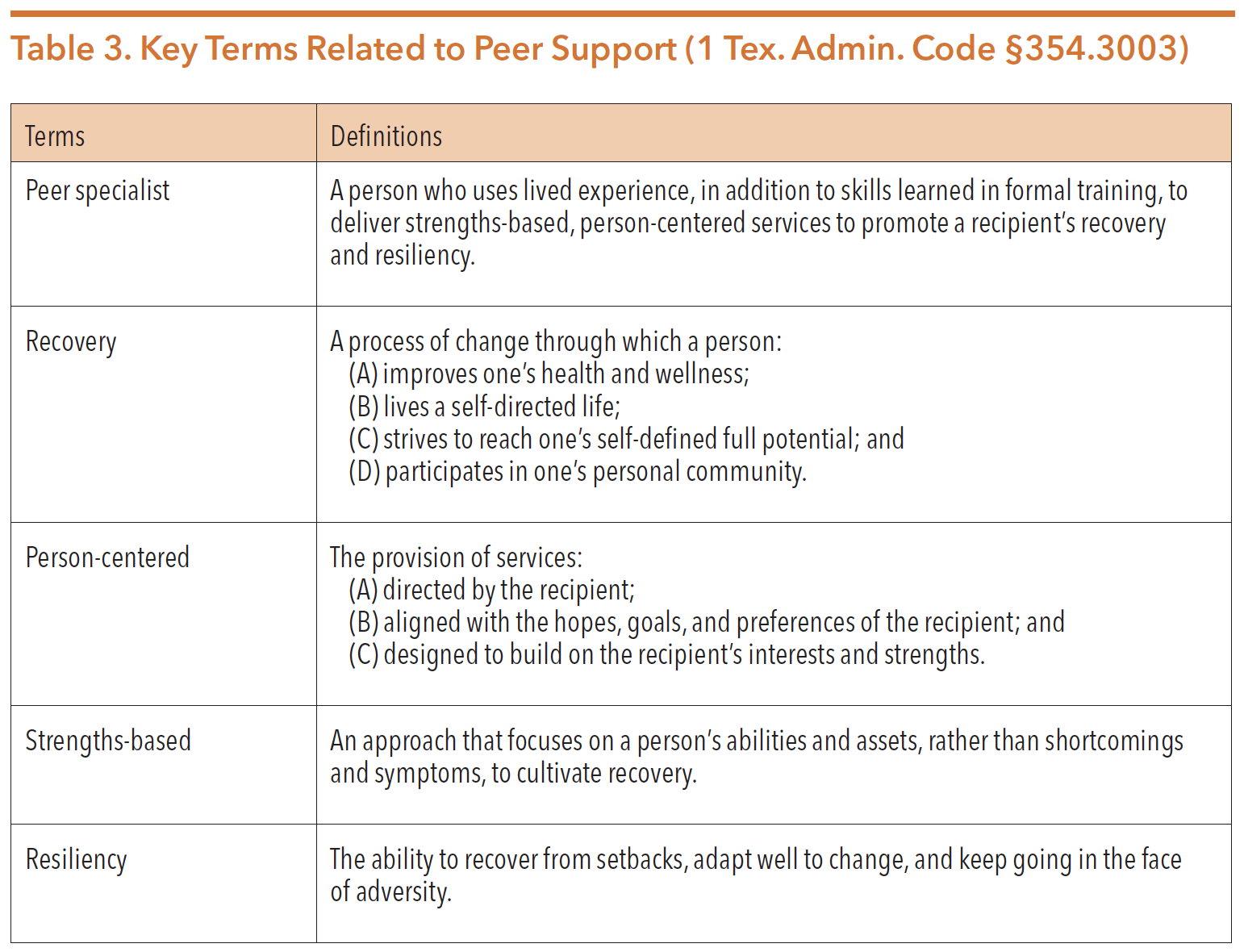

The concept of peer support services may be new to some. Table 3 below highlights some key terms.

Source: Texas Health and Human Services Commission. Medicaid Health Services, Peer Specialist Services, General Provisions, 1 Tex. Admin. Code §354.3003 (2019)

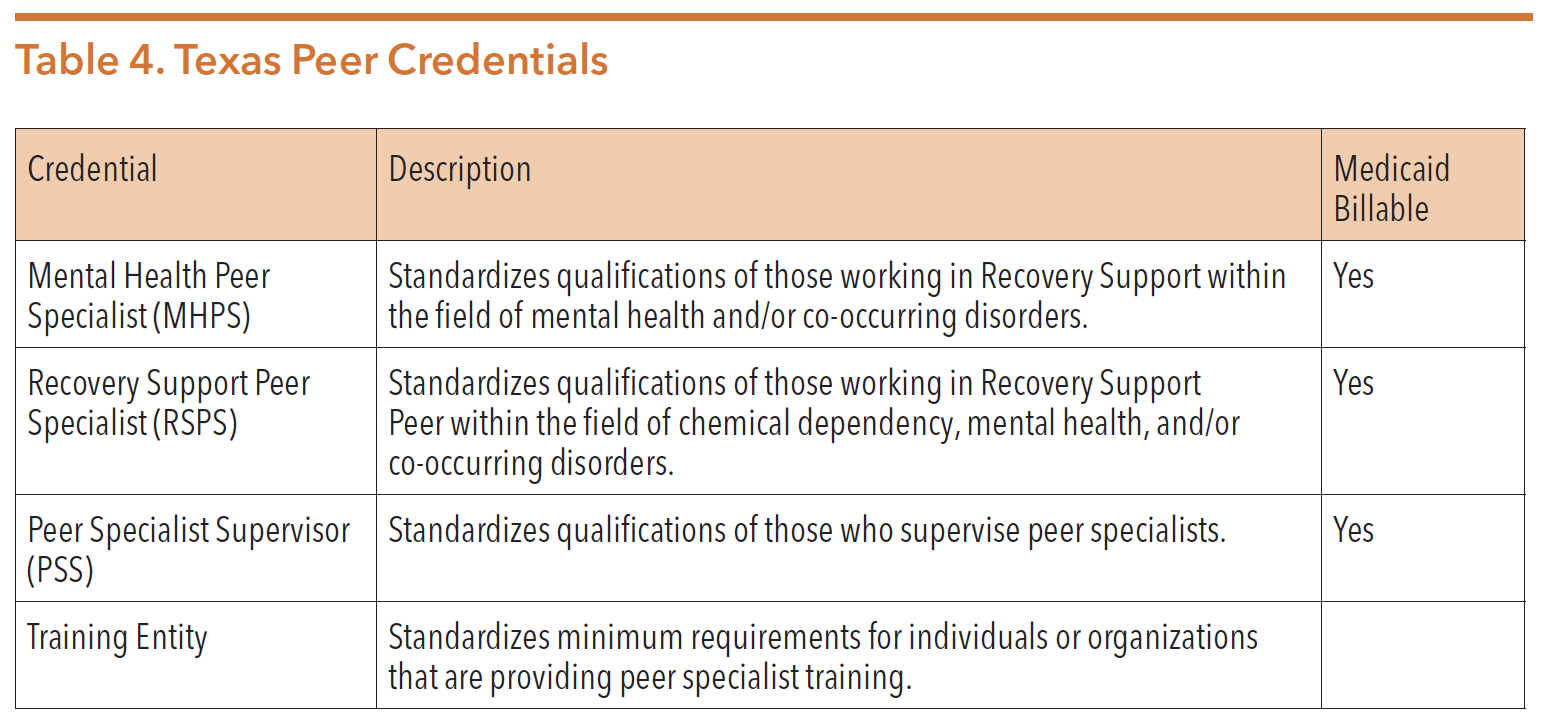

PEER CERTIFICATION

Individuals with lived experience of mental health and/or substance use conditions can be certified through the Texas Certification Board (TCB–formerly the Texas Certification Board of Addiction Professionals) and Texas Peer Specialist Certification Board (Wales Education Services). Organizations wanting to provide peer specialist training are required to be certified by the certification entities. Information about training providers/organizations is available at http://www. tcbap.org and https://texaspeers.org/. The table below illustrates the types of state certifications currently available for persons with lived experience. In addition to the certifications currently available, HHSC is working with the certification boards to develop specialized certifications for justice-involved peer specialists and family-partner peer specialists.

Source: “Certification Applications – Texas Certification Board Of Addiction Professionals.” Tcbap.org. https://www.tcbap.org/page/ certification.

Texas Health and Human Services Commission Medicaid Health Services Peer Specialist Services General Provisions, 1 Tex. Admin. Code §354.3003 (2019)

Peer specialists provide services at local mental and behavioral health authorities (LMHAs/LBHAs), peer-run service providers, state hospitals, substance use recovery community-based organizations, recovery organizations, emergency departments, treatment organizations, and more. Common tasks performed by peer specialists include:

- Helping individuals self-advocate

- Connecting people to resources and employment services

- Goal setting

- Facilitating support groups

- Outreach and engagement

- Face-to-face recovery coaching

- Telephone peer support

BILLING

While HB 1486 included provisions to allow Medicaid reimbursement for peer support services, the current reimbursement rates are extremely low, resulting in a number of organizations declining to use the Medicaid billing code. Some services provided by peer specialists can also be billed under the “mental health rehabilitation services” code that offers a much higher billing rate but can typically only be used by LMHAs/LBHAs authorized to provide mental health rehab services. There is no alternative billing code for substance use peer services. One study conducted in Michigan reported low wages and the lack of career advancement as barriers to peer specialists. The study states, “Our results indicate that certified peer support specialists (CPSS) in Michigan often experience financial fragility. CPSS wages are low relative to those of other health professionals.”

HHSC has indicated that they will be reviewing the utilization data related to peer services to determine if reimbursement rate adjustments can be made. Research shows that peer support services can save costs by curbing crisis events, decreasing emergency room visits, and potentially decreasing state hospitalization rates.

RESEARCH AND RESULTS

Nationally, peer support is an emerging field, thus long-term studies quantifying impact and return on investment are becoming more available. Current evidence suggests that peer support and coaching:

- Reduces the admissions and days spent in hospitals and increases time in the community;

- Reduces the use of acute services;

- Increases engagement in outpatient treatment, care planning, and self-care;

- Improves social functioning;

- Increases hope, quality of life, and satisfaction with life;

- Reduces substance use;

- Reduces depression and demoralization;

- Improves chances for long-term recovery;

- Increases rates of family unification; and

- Reduces average services cost per person.

In Texas, one long-term study focusing on substance use disorder peer specialists (also called recovery coaches) demonstrated exciting results at 12 months:

- Housing status improved, with 54 percent of long-term coaching participants owning or renting their own living quarters after 12 months, compared to 32 percent at enrollment;

- Overall employment increased to 58 percent after 12 months from 24 percent at enrollment;

- Average wages increased to $879 per month after 12 months from $252 at enrollment; and

- Healthcare utilization dropped after 12 months of recovery coaching:

- Outpatient visits dropped to 815 visits from 4,118 at enrollment

- Inpatient care days dropped to 1,117 days from 9,082 at enrollment

- Emergency room visits dropped to 146 from 426 at enrollment

In total, recovery coaching saved $3,422,632 in healthcare costs, representing a 72 percent reduction in costs over 12 months.

Telemedicine and Telehealth in the Time of COVID-19

Patients, providers, and health/mental health care advocates have been working to expand access to and utilization of telemedicine and telehealth services for a number of years with slow but steady progress. The COVID-19 pandemic significantly expedited this effort. Changes were approved quickly and providers adapted their practices almost overnight.

Telemedicine and telehealth is not a “service;” it is a method of service delivery (virtual visits using technology versus in-person visits). While telemedicine and telehealth works well for some services and patients, some health conditions still require in-person evaluation and testing. Telemedicine and telehealth have significantly increased access to services for many individuals with mental health and substance use conditions, but some barriers do remain.

It is important to distinguish the difference in telemedicine versus telehealth services. In Texas, telemedicine services are health services delivered via technology by a licensed physician or a provider working under the delegation of a licensed physician (e.g., nurse practitioner, physician’s assistant). Telehealth services are those services provided by licensed or certified health care practitioners other than a physician or someone working under a physician’s delegation authority. In both cases, healthcare providers are limited to the scope of services allowed under their licensure or certification.

In 2017, the Texas Legislature passed legislation requiring coverage parity for telemedicine and telehealth services. SB 1107 (85th, Schwertner/Perry) mandates payment for telemedicine and telehealth visits for a covered service, but it doesn’t mandate the same rate for the same service. Additionally, until the changes resulting from the pandemic, many of the technology and security requirements associated with telehealth services has limited the ability (or desire) of many providers to actually provide the services via telehealth/medicine. While access to mental health care services via telemedicine/telehealth has expanded greatly as a result of the pandemic, many questions still remain related to payment, rates, and parity with in-person services. Mental health and healthcare stakeholders contend that reimbursement should be based on parity, meaning that telehealth services should be reimbursed at the same rate as in-person services. Additionally, reimbursement rates should be based on the service provided and not be differentiated by the type of provider offering the services.

As of the writing of this guide, changes in service delivery requirements were granted from both state and federal authorities. While all providers remain required to operate solely within the scope of their practice, CMS and Governor Abbott have granted significant flexibility and expansion of telemedicine/telehealth services, including relaxation of some HIPPA requirements and allowing the use of audio-only telephone. Audio-only telephone has been a helpful method for communicating with people living in rural areas without stable broadband, those without easy access to technology, people experiencing homelessness, and people living in nursing facilities.

The changes listed below have been made to the delivery of healthcare services during the pandemic and represent changes that many organizations wish to see continue after the emergency orders expire. It is important to note that this is a rapidly changing environment and that much is subject to change.

- On March 14, 2020, the Texas Medical Board received approval of the governor’s office to suspend certain rules to the Texas Occupations Code and the Texas Administrative Code. The changes, which were to remain in effect until the disaster declaration was lifted, included:

- The use of telemedicine (including telephone audio-only use) to establish physician-patient relationships

- The use of telemedicine for diagnoses, treatment, ordering tests, and prescribing medications.

- Additional changes to the telemedicine/telehealth service delivery rules include:

- Telemedicine and telehealth services are reimbursed in parity with in-person visits

- Providers have a choice of technology platforms to use for service provision

- Allowing the use of telephone audio-only for service provision.

Detailed information on the changes can be found on the CMS website at https:// www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/downloads/medicaid-chip-telehealth-toolkit.pdf and the Texas Medical Association website at https://www.texmed.org/ telemedicine/.

Many stakeholders are urging the continuation of expanded ability to use telemedicine/telehealth service delivery for mental health and substance use services. On September 1, 2020, Congressman Roger Williams (R-TX-25) introduced the Ensuring Telehealth Expansion Act that would extend the expanded telehealth provisions of the CARES Act until December 31, 2025. This legislation would remove site restrictions allowing patients to receive services in their homes and would require that providers be reimbursed at the same rate as face-to-face visits.

In addition to efforts to maintain flexibility in the use of telecommunications for service delivery, strong efforts are underway to increase access to internet services by increasing broadband across Texas. As of the writing of this guide, according to the Texas Tribune, 88 lawmakers have sent a joint request to Governor Greg Abbott to “develop a plan to expand broadband access in the state.” The COVID-19 pandemic has amplified the need to ensure statewide access to internet services for not only the provision of health care services, but also for education, business, general communications, and more. According to the lead organization trying to expand broadband access in Texas, Connected Nation Texas, as broadband speeds increase, the rural areas of Texas with less broadband infrastructure fall further behind. This leads to increased disparities in access primarily for rural areas of the state.

State Hospital Redesign Initiatives

Texas psychiatric state hospital services are, in many instances, being provided in outdated facilities that need significant repair, renovation, or replacement. The 85th Texas Legislature invested in planning and development, and the 86th Legislature continued that commitment by investing $745 million for new construction and renovations at existing state hospital campuses in Austin, Kerrville, Rusk, and San Antonio. Additionally, funds are being devoted to a new hospital in Houston. Additional funding will need to be appropriated in the 87th legislative session to complete the projects already underway.

Projects currently underway include:

- Austin State Hospital – construction of a new facility to replace the current hospital is currently underway and is expected to open in June 2023. HHSC has estimated the total cost of the facility to be approximately $305 million. The new hospital will be a 240-bed facility.

- San Antonio State Hospital – construction of a new facility to replace the current hospital and renovation of an existing building is underway and is expected to open in January 2024. HHSC has estimated the total cost of the construction and renovation to be at least $369 million. The new hospital will be a 300-bed facility and the renovated building will provide an additional 40 beds on the campus.

- Rusk State Hospital – new construction of a 100-bed maximum security unit, a 100-bed non-maximum-security unit, and an administration building is planned. The total increase in bed capacity is expected to be approximately 60 additional beds costing an estimated total of $196 million. Although completion dates of the three projects are staggered, construction of all three projects is expected to be completed by November 2024.

- Kerrville State Hospital – renovation of existing campus buildings is currently underway with an expected completion date of September 2021. The renovation is expected to add 70-maximum security unit beds at an approximate cost of $30.5 million.

- UTHealth Houston Continuum of Care Campus – through a partnership between HHSC and UTHealth Houston, construction is underway for a 240-bed psychiatric hospital in the Texas Medical Center. This facility is expected to be completed by December 2021 at a cost of $126.5 million.

During the planning phases of these initiatives, it was recognized that building new hospitals and adding additional beds would be ineffective if not considered in conjunction with the continuum of housing needs. Texas needs to invest in permanent supportive housing, step-down housing, and community housing to ensure inpatient beds are used for the purpose they are designed. Without a continuum of housing available for those with serious mental illness, state hospital beds will continue to be occupied by individuals that do not need that level of care. Without the appropriate supports and services in the community, there will continue to be individuals cycling in and out of the state hospital because there is no place else for them to go.

For additional information on the state psychiatric hospital system in Texas, see the HHSC section of this guide.

Housing for People Experiencing Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorder

Housing is consistently identified as one of the biggest barriers for people in their recovery from mental health and substance use conditions. Many people experiencing serious mental illness cannot work and therefore may be eligible to receive Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits. This is often their only income. Research reveals a pronounced housing affordability gap for SSI recipients who are considered extremely low-income, making less than 30 percent of the Area Median Income. In 2020, recipients of SSI could receive a maximum of $783 a month, which is not enough to pay for the $892 fair market housing rent of a one-bedroom apartment. In 2018, 89 percent of extremely low-income households had a cost burden at the same time Texas had a deficit of 611,181 rental units affordable to extremely low-income households.

People experiencing mental illness often need tenant supports and services to remain in housing successfully, something that makes finding a place to live even harder. Due to a lack of supportive housing, a large number of people experiencing homelessness are also living with mental illness. The 2019 HUD count of homelessness in Texas found that nearly 19 percent of individuals who are homeless have a severe mental illness (over 4,800), and almost half of those individuals are unsheltered (individuals are unsheltered if they live in a place not meant for human habitation, such as: cars, parks, sidewalks, or abandoned buildings. A person who is experiencing homelessness but is sheltered can reside in an emergency shelter or some form of transitional, supportive, or temporary housing).

Some housing programs exclusively serve people with substance use conditions. Recovery housing, also known as recovery residences or sober living homes, are shared living environments that promote sustained recovery from substances and may provide a varying degree of services or supports. One example is Oxford House, which is a non-profit operating recovery homes across Texas and other parts of the country. To qualify for residency, people must contribute to the daily functions of the household and remain sober from alcohol and drugs. However, these recovery homes do not offer additional supports and services and are therefore only appropriate for those further along in their recovery. Oxford Houses receive state funding, and have expanded in Texas in recent years. Other recovery homes that offer more intensive services are available in Texas, but are less common and do not receive any state funding. In 2019, HB 1465 (86th, Moody/Menendez) was introduced but did not pass. The bill would have directed HHSC to conduct an evaluative study on the current landscape, challenges, and opportunities to expand recovery housing across the state. More information on recovery housing can be found in the Texas Department of Housing & Community Affairs (TDHCA) and Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) sections of this guide.

While people experiencing mental health and/or substance use conditions often qualify for housing programs that serve people with disabilities, there are only a small number of supportive housing programs. More information about these programs can be found here: https://hhs.texas.gov/services/mental-health-substance-use/mental-health-crisis-services/programs-people-who-are-homeless-or-risk-becoming-homeless. One example is the Supportive Housing Rental Assistance (SHR) program through HHSC. This program provides rental and utility assistance to individuals with mental illness, who were experiencing homelessness or likely to become homeless, and their families. The program provides supportive housing and mental health services to individuals in need. Priority is given to individuals transitioning from hospital settings, nursing facilities, forensic units, and individuals identified as frequent users of crisis services. This program is a partnership between HHSC and LMHA/LBHAs. Currently, SHR program funding allows the program to operate at 30 of the 39 LMHA/LBHAs. In January 2020, HHSC began developing a Housing Choice Plan that is expected to be published in December 2020 or January 2021. The purpose of the plan is to improve housing options for individuals with mental health conditions, IDD, criminal justice involvement, and/or substance use conditions. To inform the plan, HHSC:

- Convened a workgroup of stakeholders consisting of state agencies, individuals with lived experience, and organizations;

- Surveyed state agencies on housing activities;

- Held focus groups; and

- Conducted a statewide survey of individuals with lived experience, caregivers, advocates, and providers. HHSC initiated over 4,000 surveys across the state and was able to procure a 90 percent completion rate. The survey revealed:

- The largest challenge for individuals with IDD, mental health conditions, and substance use conditions was lack of financial ability to procure their desired living situation. Other common challenges were inability to find housing in their community, criminal records limiting housing options, and past landlord experiences limiting their housing options.

- A majority of respondents reported that the most needed supports to obtain desired housing was community resources navigation, transportation, and managing money.

- Additionally, a majority of respondents with substance use conditions reported needing recovery support services.

The scope of the workplan includes an environmental scan of existing housing options, gaps and barriers in the state’s housing system, and recommendations. While conclusive takeaways from the workgroup had not been finalized at the time of writing, below are some areas in which the workgroup had identified housing gaps, barriers, and recommendations specific to individuals with mental health conditions.

- The identified gaps include a lack of:

- Affordable housing;

- Opportunities for homeownership;

- Financing for permanent supporting housing; and

- Development of group homes, residential treatment facilities, transitional housing, and step-down/step-up housing.

- The identified barriers include:

- Poor quality boarding homes;

- Confusion around tax credit programs;

- Stigmas held by the public/landlords/developers;

- Lack of awareness of one’s own mental health or substance use condition; and

- Strict eligibility criteria for the Home & Community-Based Services — Adult Mental Health (HCBS—AMH) program.

- Overarching recommendations revolve around: Creating a landlord risk mitigation fund;

- Providing training to tenants and housing providers on reasonable accommodation;

- Providing life skills training to individuals who need assistance maintaining housing; and

- Developing a person-centered discharge plan that includes identification of long-term housing options.

In the 86th Texas legislative session, HB 2564 (86th, White/Lucio) passed. The bill addresses the homeless youth population by requiring TDHCA to include foster youth in their low-income housing plans. HB 4468 (86th, Coleman/Whitmire) eases the match requirement for counties with less than 250,000 people for the Healthy Community Collaboratives Housing program. HB 1257 (86th, Rosenthal), which failed to pass, would have given counties the authority to bar discrimination against tenants receiving funds for housing assistance. Housing is a complex issue, but Texas’ rapid population growth coupled with disastrous events such as COVID-19 will continue to make it a relevant issue moving forward for the Texas legislature and mental health stakeholders.

Children’s Mental Health and Well-being

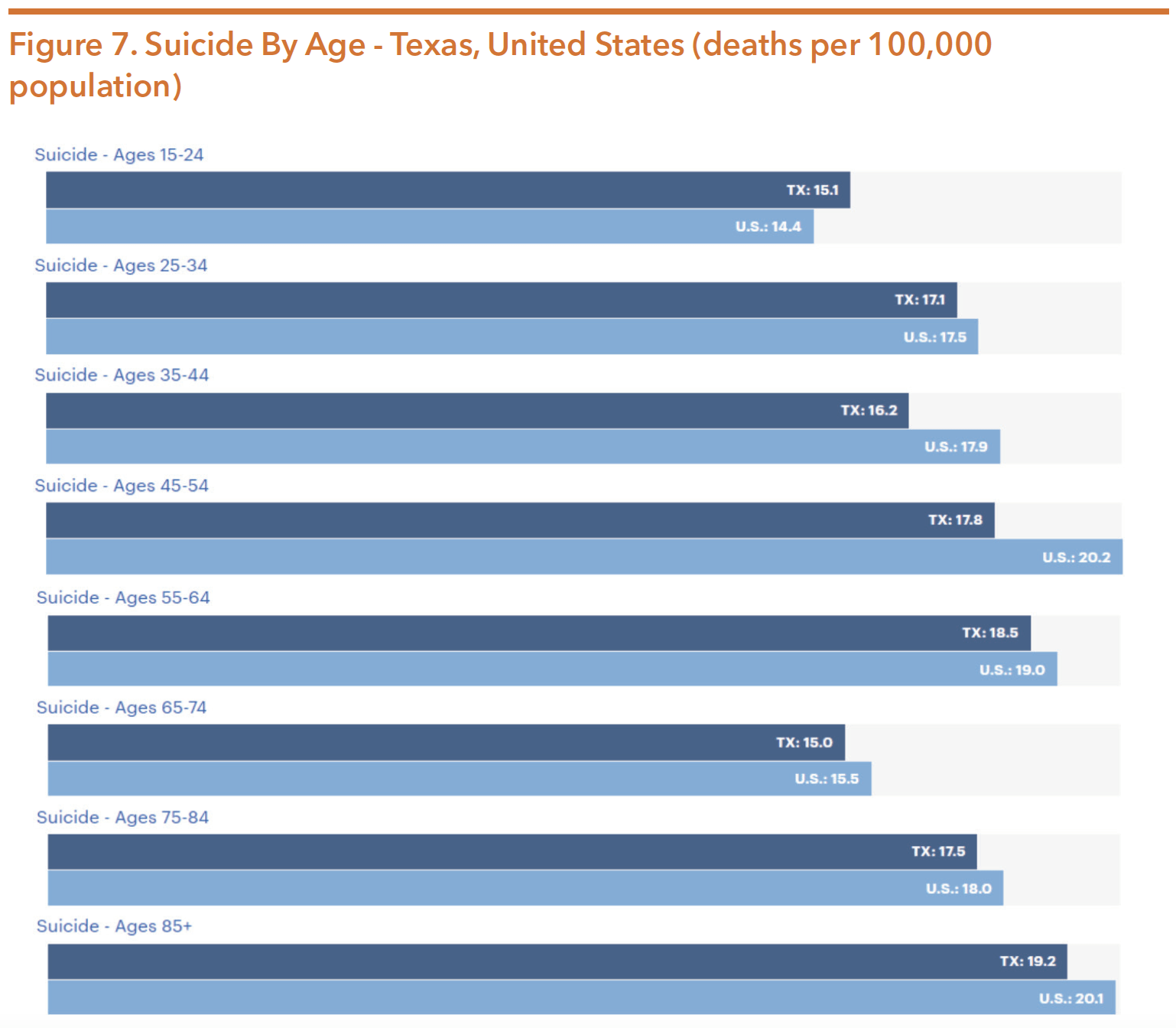

Tragic school shootings and an increase in youth suicide rates brought a heightened focus to the mental health of youth in Texas. Texas children and youth experiencing mental health concerns is common across the state. These needs can range from supports and services for a diagnosable mental health disorder to a more universal need for support of social and emotional well-being.

- In 2019, 38 percent of Texas high school students reported feeling sad or hopeless for a period of two weeks or longer that resulted in decreased usual activity.

- In 2019, one in ten high school students in Texas reported attempting suicide during the 12 months before the survey.

- In 2019, suicide was the second leading cause of death in those aged 15-34 in Texas.

- In 2019, one in five children in Texas were estimated to have experienced multiple adverse childhood experiences (ACEs).

BARRIERS TO SERVICES

Lack of access to behavioral health supports can have a serious and lasting impact across all areas of a child’s life. Leaving children and their families without support and services contributes to school drop-outs, unemployment, and potential involvement with the juvenile or criminal justice systems. Approximately 70 percent of youth who need mental health treatment do not receive it. Of those who are able to access services, only one in five children receive mental health specialty services. Unfortunately, even when specialty services are accessible, 40 to 50 percent terminate treatment prematurely due to various barriers such as lack of transportation, financial constraints, and stigma.

The behavioral health workforce shortage has been a barrier to receiving supports and services. This shortage is even more dire for youth specialty services. There has been a growing recognition that many mental health needs of youth are diagnosed and treated in settings other than psychiatry due to the severe shortage of child psychiatrists and other mental health professionals throughout the state. In 2018, there were only 690 Child and Adolescent Psychiatrists (CAPs) across the entire state of Texas. Consequently, the majority of mental health services are provided by professionals other than psychiatrists in many parts of Texas where there are significant shortages of these providers . As of June 2020, Texas had only met about 36 percent of the state’s need of mental health professionals and 214 counties were designated as either full or partial Health Professional Shortage Areas for Mental Health (HPSA-MH). While access to specialty mental health care is often limited, families without resources or insurance have even more difficulty. Unfortunately, Texas leads the country in uninsured rates of children.

One solution to address the mental health workforce shortage is to make peer support services and family partner support services more readily available to youth and their families. During the 85th Texas legislative session, HB 1486 (Price/ Schwertner) passed to make peer support services a Medicaid reimbursable state plan benefit. However, during rulemaking, youth were determined to be ineligible to receive peer support services despite these services being critical for youth and young adults. HHSC specified that an individual 18 and older could be a certified peer specialist, however, an individual is required to be 21 years of age or older to receive these services.

DISPARITIES

While gaps and barriers exist for youth and families to access behavioral health services, there are often additional difficulties certain youth face. These youth are often at higher risk of behavioral health concerns, and frequently do not receive services or receive services in inappropriate settings.

- LGBTQ youth are at least twice as likely as non-LGBTQ youth to attempt suicide, and gay and bisexual male youth are 15 times more likely to face substance use issues than the general population.

- Latinx children have the lowest rate of public or private health insurance coverage of any ethnic group.

- Black and Latinx children and youth experience higher rates of entry into juvenile justice and child welfare.

- Black and Latinx children have the highest rates of unmet need for mental health services.

- The prevalence of diagnosed mental health disorders in individuals with intellectual disabilities is estimated to be between 32 percent and 40 percent, compared with approximately 20 percent in the general population.

- Foster care youth are more likely than the general population to have a mental health concern.

- Justice-involved youth have higher rates of mental and behavioral health problems than their peers, including the onset of severe mental illness.

STUDENT MENTAL HEALTH AMID COVID-19

The 2019-2020 school year presented additional challenges for students and school personnel as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. It can be expected that those challenges will continue and evolve during subsequent school years. Students and educators will be navigating unique and changed communities, as well as classrooms and schools. While data has not been collected to analyze the effects of the pandemic on the mental health of Texas students, data that is available indicate cause for concern.

An early study in China of over 2,300 students who were in lock-down for an average of 33.7 days found that 22.6 percent reported depressive symptoms and 18.9 percent were experiencing anxiety. Further, as Texas experiences the economic implications of COVID-19, data shows that increased unemployment is associated with increased child abuse and neglect, increased incidence of injuries, and worsening of child and adolescent mental health. As students return to their classrooms and others remain online, supporting their mental health and well-being will be imperative.

Learning is inextricably connected to a student’s mental health. Positive behavior supports and interventions, as well as various models of social-emotional learning programs within a multi-tiered system of support, can help build positive learning environments. These programs are primarily school-based initiatives aimed at prevention, but also provide increased support for children identified as being at higher risk for behavioral challenges. More information on these programs can be found in the Texas Education Agency section of this guide.

EXCLUSIONARY DISCIPLINE AND THE SCHOOL-TO-PRISON PIPELINE

Despite the lack of evidence that exclusionary discipline is an effective method of changing students’ behaviors in schools, it is often used. One in ten Texas students were suspended, expelled, or placed in an alternative education program during the 2018-2019 school year. Students with disabilities and students of color are disproportionately affected. Despite making up a smaller percentage of overall student population, they are disproportionately removed out of their classrooms more than White students and those without disabilities.

Unidentified mental health conditions, substance use, or trauma can be perceived as “bad” behavior, and punitive discipline practices may be implemented. The effects of punitive discipline often negatively affect students’ senses of safety, well-being, and abilities to learn. Some students may attend schools in communities with few resources or have supports that serve their particular, unique needs. When there are no other resources at hand, classroom removals are often implemented.

Research shows that exclusionary discipline increases the likelihood of lowered academic performance, dropping out, antisocial behavior, and future contact with the justice system. School exclusion is a central element in the school-to-prison pipeline, and has been a focus in numerous studies. Evidence proves a strong relationship between exclusionary discipline and academic failure, arrest juvenile justice system involvement, criminal justice system involvement, and incarceration.

As Texas students return to their classroom post COVID-19, support and guidance to schools on how to best support the mental health and well-being of students will be essential. Rather than punitive discipline as a response to unaddressed mental health conditions or trauma, it will be imperative that kids remain in their classrooms.

Foster Care Redesign and Community Based Care

A majority of youth entering foster care have experienced some form of trauma, highlighting the need for the Texas foster care system to support youth mental health. These youth have often experienced psychological, sexual, or physical abuse, as well as neglect. This can lead to higher rates of physical and behavioral health issues, substance use, and criminal justice involvement in adulthood. Symptoms of trauma are often interpreted as problematic behavior that are a result of issues unrelated to trauma. These symptoms can be worsened by inconsistency in child placements that send youth outside their home communities.

COMMUNITY BASED CARE

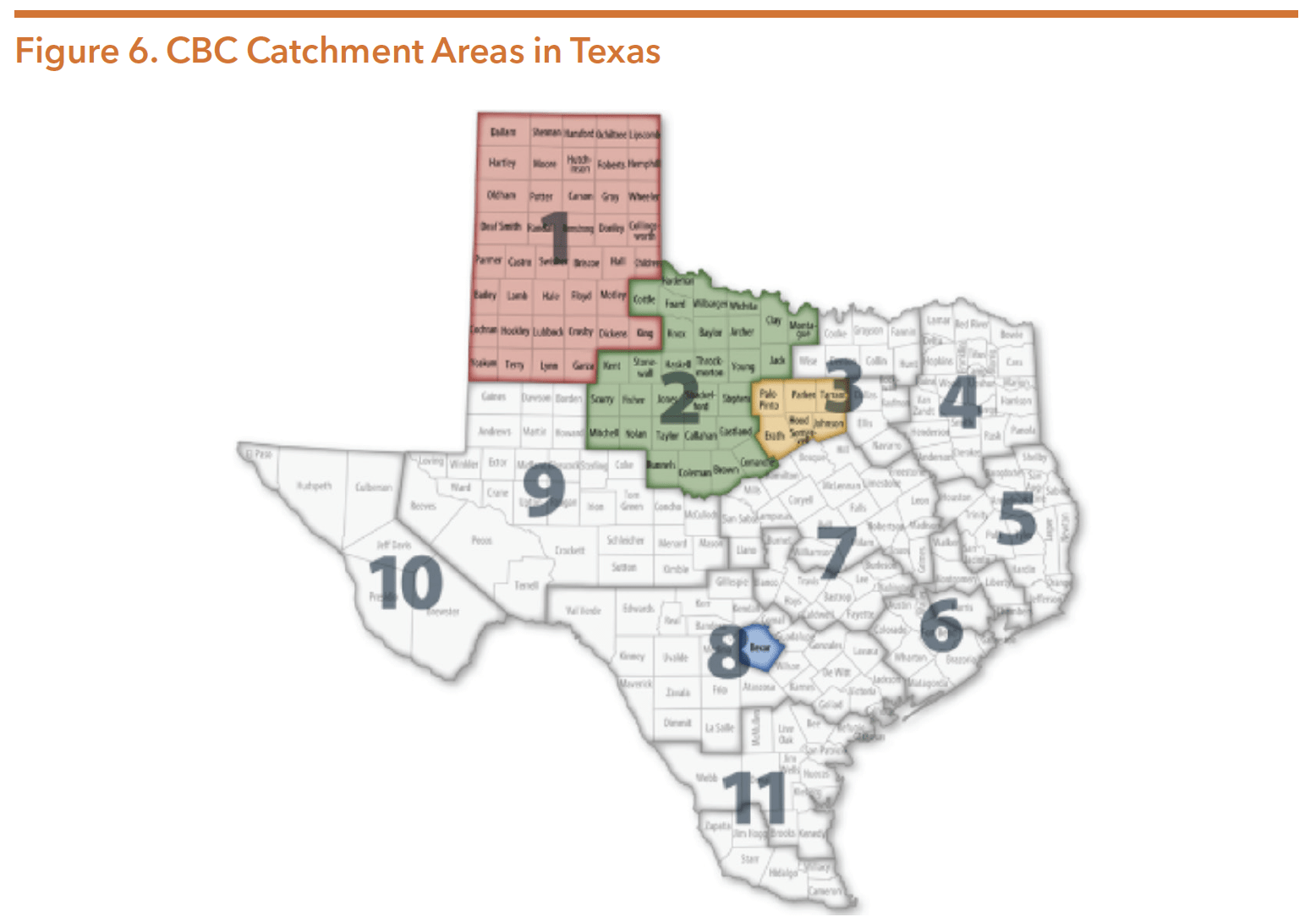

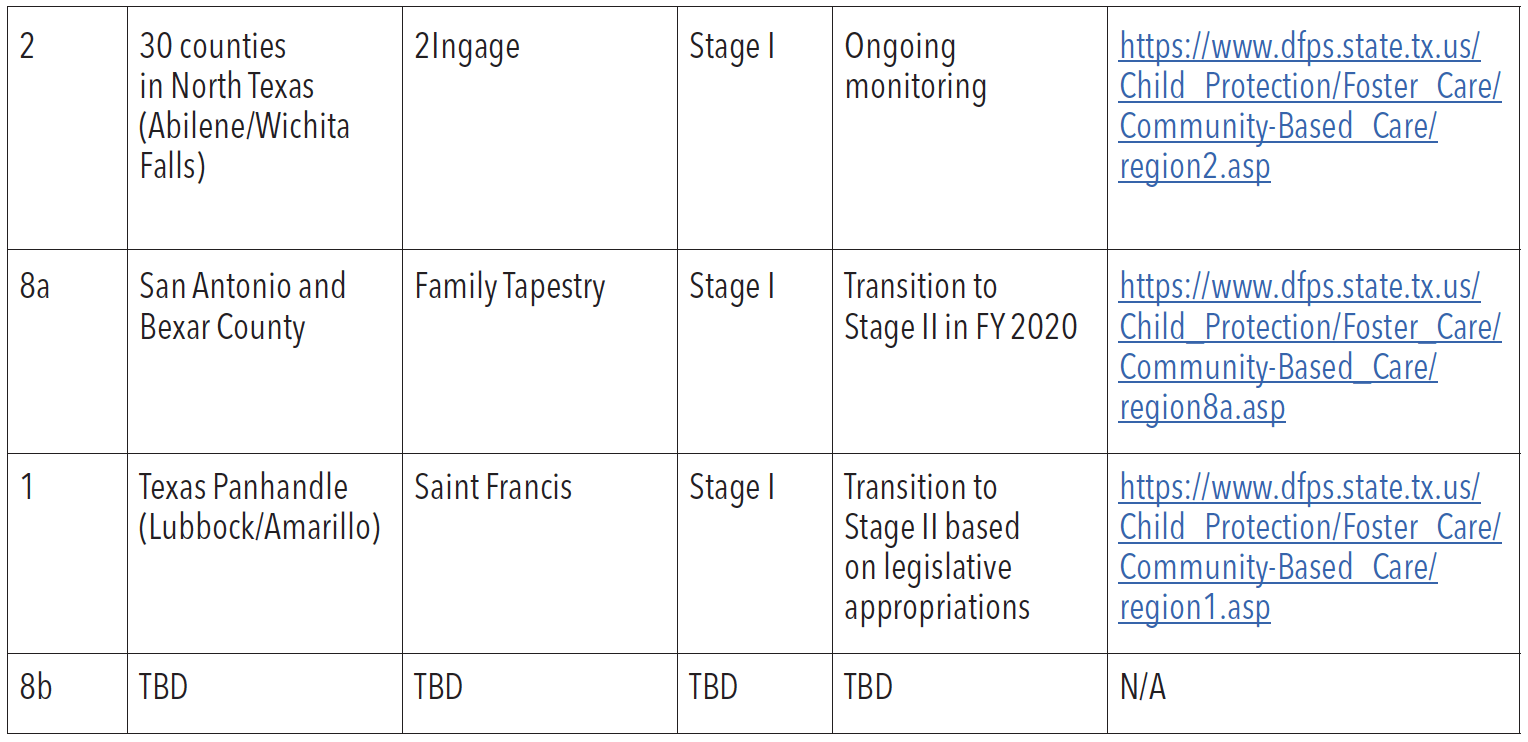

In 2010, the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS) established the Foster Care Redesign Project known as Community-Based Care (CBC). This project is a new way of providing foster care and case management services through a community-based approach to meet the needs of children, youth, and families. CBC is meant to enhance safety, permanency, and well-being of youth in state conservatorship. DFPS contracts with a single source continuum contractor (SSCC) within a specific geographic area shown in Figure 6. Each SSCC is responsible for finding foster homes or other living arrangements and providing a full continuum of services, including mental health treatments and supports. To incentivize youth to be placed in the most appropriate service level, CBC transitioned the foster care system’s reimbursement structure. CBC funding is now performance-based and linked to positive outcomes in a child’s care rather than service level. With the assistance of DFPS’s Child Protective Services and Texas CASA, SSCCs prioritize kin placements between youth and biological family members when possible.

Source: Texas Department of Family and Protective Services. Community-Based Care. Retrieved from https://www.dfps.state. tx.us/Child_Protection/Foster_Care/Community-Based_Care/default.asp

CBC is being implemented in two stages:

- Stage I – an SSCC develops a network of services and provides foster care placement services. The goal is to enhance general well-being of youth in foster care by keeping them close to home and connected to their communities.

- Stage II – the SSCC provides case management, kinship, and reunification services. The focus is on increasing services for families and permanency outcomes for youth.

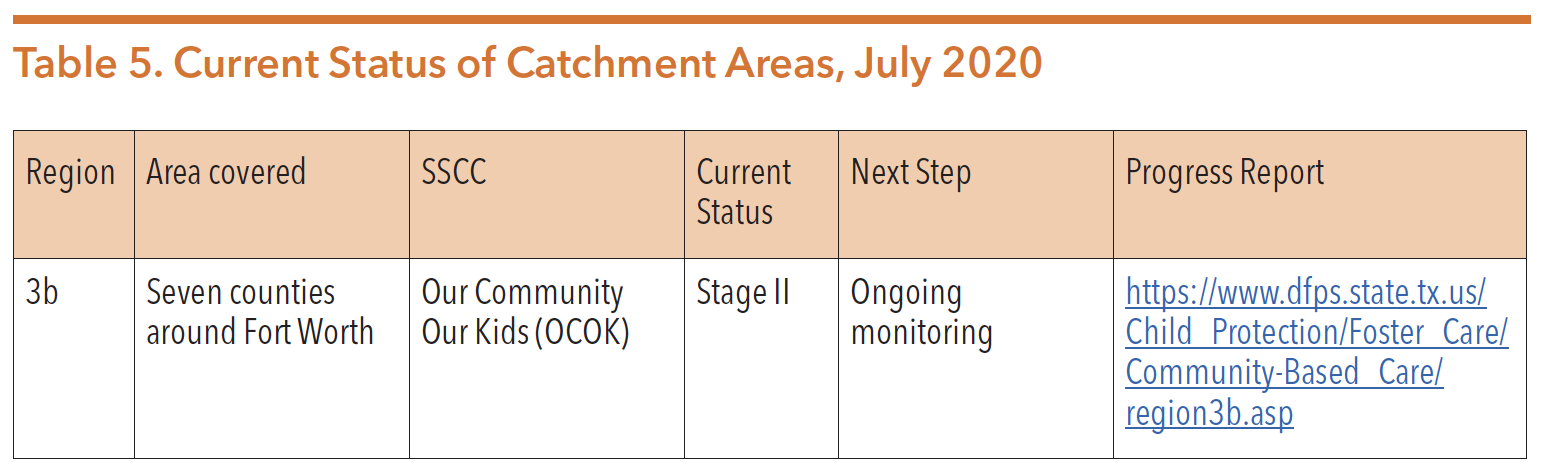

As of August 2020, CBC serves around six percent of all youth in foster care and about two percent of all forms of substitute care. Table 5 shows the current catchment areas currently using CBC:

Source: Texas Department of Family and Protective Services. Community-Based Care. Retrieved from https://www.dfps. state.tx.us/Child_Protection/Foster_Care/Community-Based_Care/default.asp

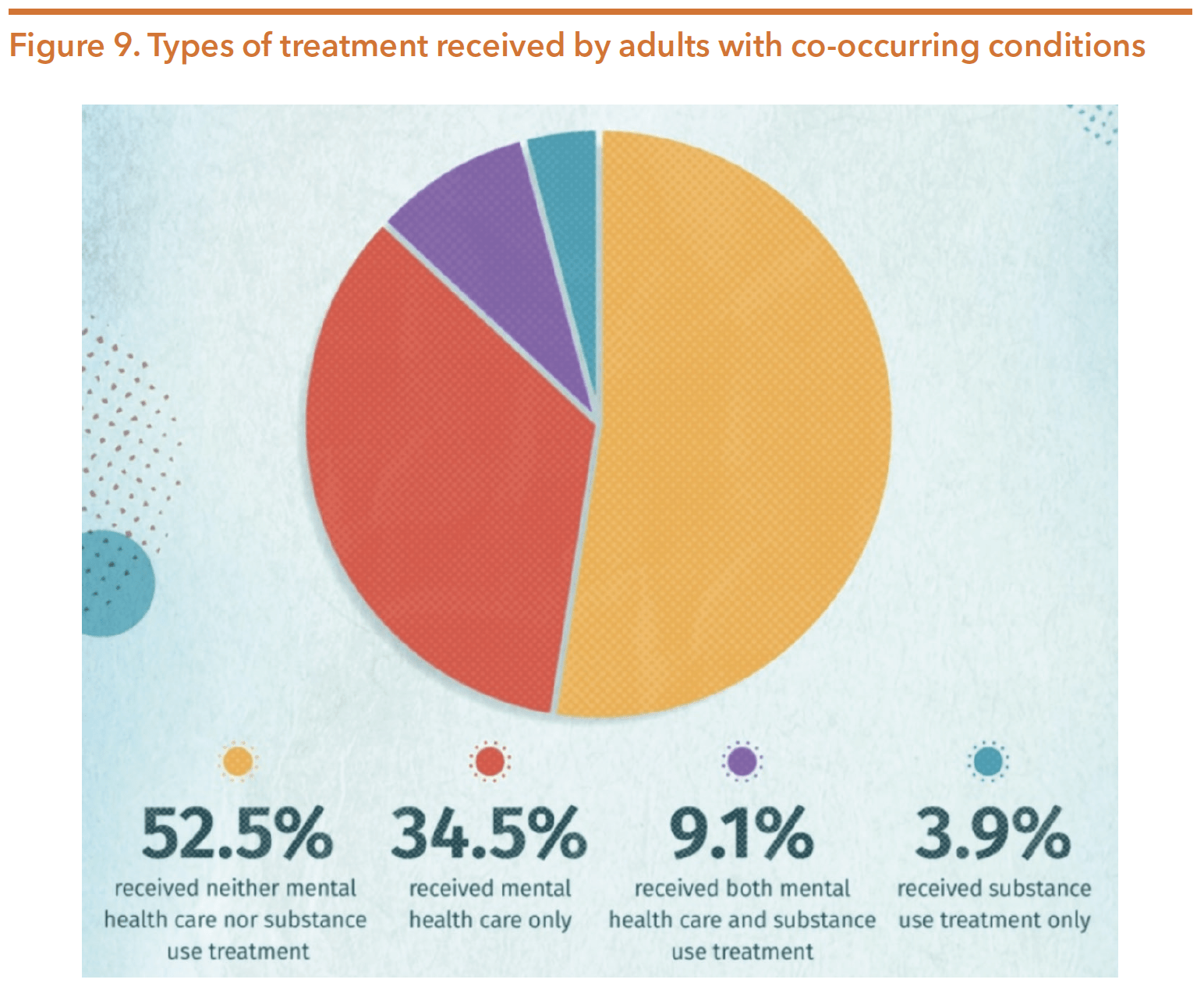

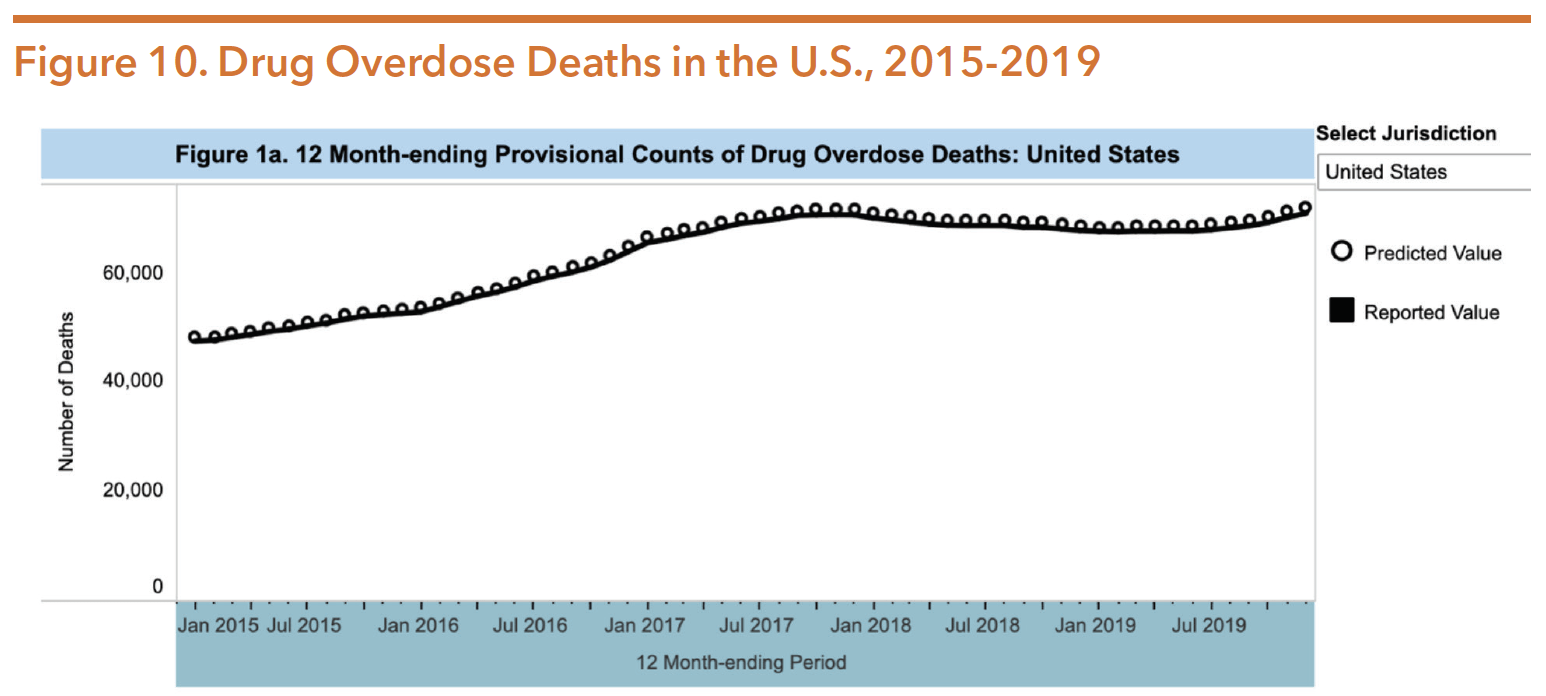

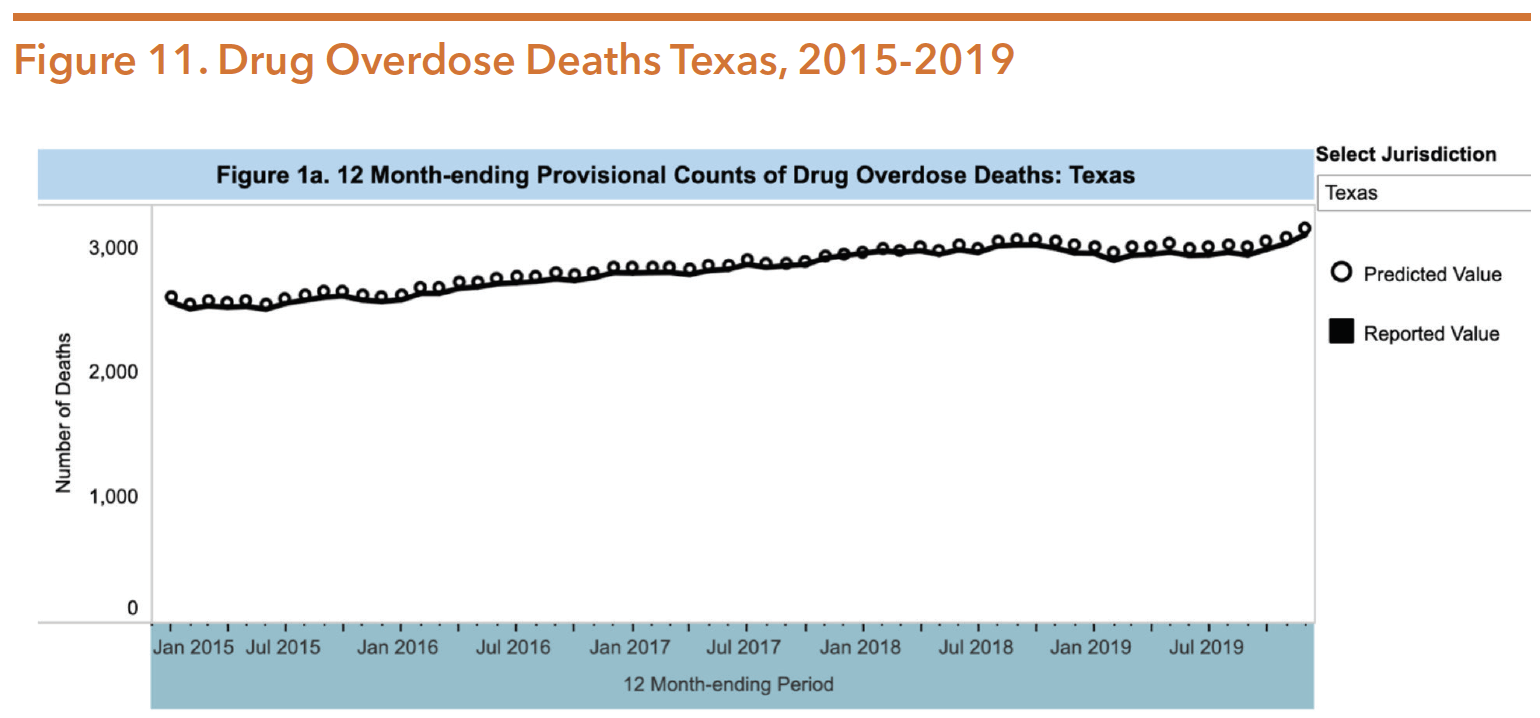

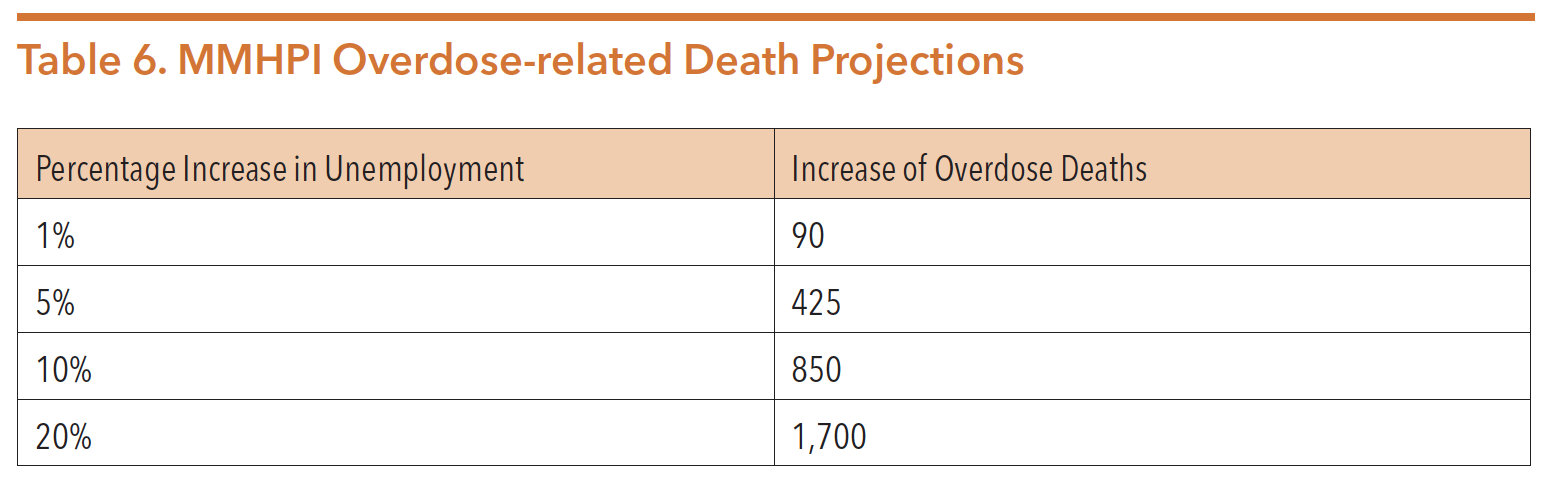

For more information on CBC progress in various catchment areas, see the below reports: