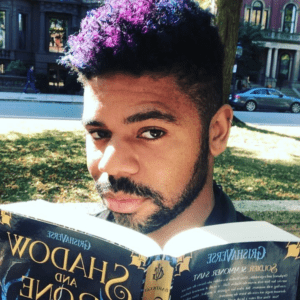

Dr. Chase Anderson

As we enter 2021, most of us are beyond exhausted, wondering how much longer this pandemic will go on, what the post-pandemic normal will look like, and what help we can count on. In many ways, these awful circumstances serve as a reminder of just what a moral pivot point the Black American experience has been and continues to be. We are joined on this episode by Dr. Chase Anderson, fellow in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at the University of California San Francisco, to discuss the limits of how helpful our professional identities can be while experiencing racial grief at this time.

Writing and Communicating about Racial Grief

Anderson recently published a piece for STAT with the headline “I’m a black psychiatrist. I’m never prepared for the emptiness and grief I feel when police shoot a black person.” In the essay, Anderson describes the rage he feels at seeing such horrors again and again and again – and the instinct to transmute that anger into something else, out of self-protection. “To be an enraged Black man in America can be lethal – we’re killed even when we aren’t upset,” the piece reads. Anderson says he wrote this piece because he wanted people to feel seen, especially those whose voices have been historically silenced.

“I think the way we communicate about minoritized people is pretty violent,” says Anderson. “Are we seeing white people splashed across the papers in their desecrated bodies? No. And people still care about those people who are being injured at that point. Why do you need to see images of Black people actually being killed to actually care?”

Being Pigeonholed by One’s Blackness

Far from being stifled – or, at least, only stifled – these days, some Black Americans, like Anderson, are sought after for commentary on race matters. Some even experience a degree of hyper-visibility because of their race. This brings up the double bind of wanting one’s blackness seen, but also not wanting to be pigeonholed by it.

Anderson sees this across America and gives an example from Twitter. “A lot of people say, ‘Who’s a Black physician I should follow?’ instead of staying, ‘Who is a person who speaks about race or racism I should follow?” Anderson says he thinks this boxes Black people into only speaking about race. “The way I work against that is that I actually talk about other things. I talk about loving Sailor Moon and Charmed and K-pop, and I make sure to actually weave that into some of my articles now, to show that I am much more than just somebody who is Black and gay. Those are facets of myself, but they are not all of who I am.”

Anderson says he sees it as an enormous privilege to be able to communicate about things like his race and identity. “People who are minoritized too often do not have their stories heard or they have them told in a way that is through a white perspective. They also are often silenced by their own places that they work or places that they try to submit pieces of writing. I try to speak to those experiences while also showing that I am much more than just those experiences.”

Practices to Sustain Resilience

Through all of this, one must find and sustain their own personal practices for building resilience. For Anderson, those practices include connecting with friends and family for support, especially through experiences of racism and stress. In addition, Anderson is an avid reader, especially fantasy books. “I like reading fantasy books because I think it shows a better path and a way we could move beyond where we are now, and that’s something I always keep in mind.”