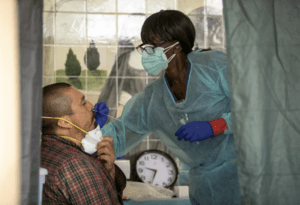

Photo: Jay Janner/Austin American-Statesman

It’s become accepted wisdom at this point: coronavirus is not a color-blind adversary. Ten months into the pandemic, it bears repeating: this pandemic is unequivocally hitting communities of color the hardest. The data that we have clearly shows that vulnerable communities in Texas, especially Black and Latino communities – who already face disproportionate instances of diabetes, kidney disease, and other chronic illnesses – are more likely to experience negative outcomes if infected by the virus.

Before its shuttering, the Office of Minority Health Statistics and Engagement was doing revolutionary work interrogating racial disparities in health and human services. The office did more than just report instances of disproportionalities – they were accountable for working with communities where disparities existed and strategizing with them to come up with policies and programs that were community-driven and that prioritized equity.

The evidence shows, and common sense tells us, that more complete and accurate data on race and ethnicity can improve the ability of public health systems to eliminate health disparities by reducing inequities. This could result in improved access to health services where it is currently desperately lacking– including mental health. Funding to re-establish an office at the Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) to focus on health inequities and remove disparities should be a priority for Texas. Without such an office, accountability is absent.

The HHSC Office of Minority Health Statistics and Engagement was created in 2011(under a different name) and was subsequently disbanded in 2017 when funding was quietly eliminated from the Texas biennial budget. This has left a gaping hole in the system with no one accountable for addressing racial disparities in our health and human services system. While disparities exist across state agencies, disparities in health and human services are often the most damaging and penetrate broadly into other systems.

Their work highlighted barriers to opportunities and provided policy recommendations for Texas systems of mental health, education, juvenile justice, child welfare, health, and employment for people with disabilities and minorities.

And while all states vary in how they report COVID-19 cases, Texas is one of the worst, reporting race and ethnicity data for a mere 3% of its COVID-19 cases. Some have suggested that if the Office of Minority Health Statistics and Engagement still existed, these racial disparities could have been better investigated and reported, or perhaps even prevented.

Texas needs an office of health equity dedicated to collecting and analyzing data and developing strategies to repair the damage that has been done. We must ensure that our state is ready to respond to the disparate needs of all Texans, including the ongoing effects of the COVID-19 crisis, which will undoubtedly be felt for years to come. In recent months there has been a renewed push to revive the office whose aim is to eliminate disparities, and we are hopeful that policymakers will see the wisdom in doing so.