This post is part of the Hogg Foundation’s “3 Things to Know” blog series, which explains concepts influencing community mental health and our grantmaking. Check out others in this series: Recovery, Healthy Equity, Social Determinants of (Mental) Health, Resilience and Well-Being.

This post is part of the Hogg Foundation’s “3 Things to Know” blog series, which explains concepts influencing community mental health and our grantmaking. Check out others in this series: Recovery, Healthy Equity, Social Determinants of (Mental) Health, Resilience and Well-Being.

At the most basic level, trauma-informed care (TIC) can be defined as services and supports that are informed by a deep understanding of what trauma is and how it affects people. Training caregivers to deploy a trauma-informed approach when working with patients has been proven to increase the efficacy of treatment.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) identifies six principles that structure a trauma-informed approach: safety, trustworthiness, empowerment, collaboration, peer support, and history, gender, and culture. These values speak, in one way or another, to certain aspects of social life that traumatic experiences can leave in a state of disrepair.

Here are three things to know about trauma-informed care:

1. Trauma-informed care should start early.

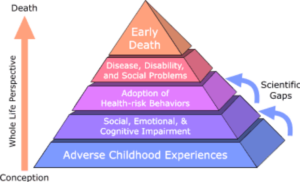

The Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC) describe Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) as “potentially traumatic events” that afflict children and teenagers up to 17 years of age. Because ACEs frequently take place in the home or in relation to family members, they destabilize a child’s early sense of self, safety, and belonging. Later in life, survivors are more likely to engage in risky health behaviors, develop chronic substance use disorders, or lose their ability to develop meaningful social and emotional bonds—all factors that don’t just lower their quality of life, but shorten it.

An infographic developed by the CDC, based on a joint study with Kaiser Permanente conducted in the mid-1990s, illustrates how the cumulative consequences of ACEs on survivors can not only last a lifetime, but also root deep enough to affect communities and society at large. It is trauma-informed community and public health responses, however, that can either help survivors understand and manage their symptoms or prevent ACEs from occurring in the first place. Creating programs, service centers, and other environments where children feel nurtured and protected from harm, as well as training primary care providers to recognize and respond to signs of trauma, are two strategies that start healing and prevention early.

2. Communities need trauma-informed care, too.

Although communities can band together to treat and prevent trauma, they can also be banded together due to a collective experience of trauma, or what the Prevention Institute calls adverse community experiences. Like ACEs, the kinds of trauma carried by an entire community take many forms and persist across space and time. In the wake of violence or disaster, pervasive feelings of disempowerment and distrust can rise up and bury deep.

Community trauma might occur due to a single hard-hitting event with lasting consequences, like Hurricane Harvey, or as an intergenerational legacy of structural violence that warps the fabric of everyday life. The latter is the focus of a guide to trauma-informed community building created by the Urban Institute that identifies strategies like peer support, creative expression, and community organizing as means of collectively responding to trauma caused by social injustice and inequity.

3. There is no area of life that a trauma-informed approach cannot touch.

Not all institutions may recognize the value of bringing a trauma-informed approach to their work. But for trauma-informed care to truly help communities build resilience and find healing over time, some form of it must be available in most—if not at all—of the domains and environments that structure a person’s everyday life. This is especially true for religious and educational institutions, where children and young adults who are living with or are more vulnerable to ACEs are perhaps more reachable by counselors, instructors, and staff than any other setting.

Neglecting to bring trauma-informed care into places where it is so greatly needed does damage that only becomes more visible and unmanageable over time. But embedding trauma-informed practices in the people, places, and systems encountered day to day can, in the long run, yield legitimately transformative results.