Image credit: Atlanta Black Star

The teaching of history, like so much else in the present day, has become a political hot button—and The University of Texas at Austin hasn’t been spared. Over the last several months the campus has been roiled by controversies over the names of buildings, the placement of statues, and even the venerable “Eyes of Texas” song. And a largely ginned up controversy over “critical race theory” has been used to cast suspicion on the history profession as a whole.

These developments worry historian Dr. Peniel Joseph, our guest for this episode. The founding director of the LBJ School’s Center for the Study of Race and Democracy and the author of award-winning books including Waiting ‘Til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America and Dark Days, Bright Nights: From Black Power to Barack Obama, Dr. Joseph sees our present moment as a referendum on the U.S.’s commitment to equal citizenship.

“I’m very concerned,” says Dr. Joseph. “I think the assaults on teaching about the history of white supremacy in this country, the history of racial slavery, the history of both the denial of Black citizenship and dignity but also the struggle for—and how Black people have changed this country in terms of through music, the Black church, our intellect, our dance, our aesthetic, our democratic aspirations—it’s catastrophic.”

Why History Matters

Despite this, it remains the case that history plays a role in mental health and well-being, and has many important things to teach about it. We have previously explored historical trauma and its present-day connection to mental health, but Dr. Joseph adds that history sheds important light on the material basis of well-being.

“I think the largest way our mental health is impacted is really the wealth disparity, and the disparity in power relations between Black people and the rest of the country,” says Dr. Joseph. “Because it is that wealth inequality that leads to the destruction of Black citizenship and dignity because wealth allows people to amplify their political power and have their communities thrive.”

But historians are made, not born. Dr. Joseph credits his intellectually adventurous upbringing for sparking his love of history.

“I think that’s my mom’s story,” says Dr. Joseph. “My mom always told us histories about the Haitian Revolution, about Black women and Black women’s activism and Black feminism. That’s one of the reasons why by the time I went to Temple University. I studied with Sonia Sanchez the renowned and iconic poet, and Black feminism was one of my fields of study 28 years ago.”

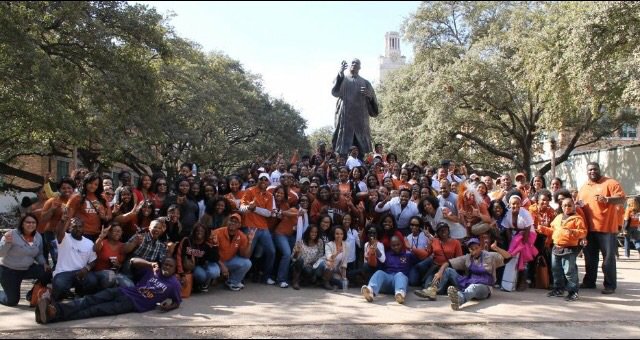

Along with this professional devotion comes what Dr. Joseph describes as his embrace of a model of servant leadership that involves, above all, being present and available to students of color. He documents the mental strain, the feeling of vulnerability and exposure, that pervades student life on campus.

Last summer’s George Floyd protests were a turning point, a generational touchstone for students who already had to process years of police killings of Black people. For Dr. Joseph this points up “the way in which that violence and death and exploitation impacts Black student wellness and mental health, and the way in which they’ve been called on, without pay or remuneration, to become ‘race experts’ and to sort of be ‘diversity experts’,” all the while lacking the financial, emotional and spiritual supports necessary to tend to their own mental health.

Climbing the Hill

And Dr. Joseph sees a similar dynamic at play when it comes to his own prominence and visibility as one of the few Black historians on campus. With so much of his life lived in service to others, it is not lost on him how important work-life balance and emotionally replenishing rituals are to his mental health.

“I think a lot of times we refuse to talk about the emotional impact and assaults that white supremacy inflicts on us,” says Dr. Joseph. “By nature, I’m an optimistic person, I’m a person who sees things as the glass half-full, and sees opportunities even amid challenges and conflicts.”

“But I can get depressed as well, and I can get sadness and ennui about the state of the world and certainly the state of Black America.” Dr. Joseph naturally uses history as one coping mechanism. He also finds solace in Black expressive culture—music, dance, film and art whether “high” or “low”—as well as his regular spiritual practice born from, as he puts it, “Black Southern Baptist-by-way-of New York City” tradition. He practices yoga. And then there’s his students.

“I’ve been doing this now for over 25 years, and the interesting thing is the deeper you get into it the less you know,” Dr. Joseph says with a laugh. “By the time you’re facing your students your students might think ‘Wow, this hill, how am I going to climb this hill?’ but you’re on the same journey with them. You just might be a little further ahead.”