Beginning in the 1970s, the fracturing of underfunded mental health resources to private sector service providers and community-based organizations has meant that “numerous individuals with mental illness…slip through the cracks, sometimes turning up in homeless shelters” or on the street (Bush, 2016, p. 149).[i] This is especially true for people of color, who are more likely than their white counterparts to experience both housing and medical discrimination. In states like Texas, where investment in mental health and substance use resources was already limited, communities were particularly hit hard by this fracture. The first federal legislation acknowledging and taking steps to end homelessness was the 1987 Stewart B. McKinney Homeless Assistance Act, which created the Interagency Council on the Homeless to fund various types of assistance programs.

Understanding the Homeless

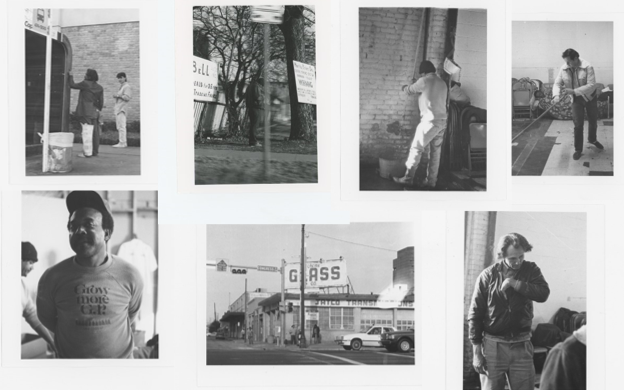

The following year, in 1988, the Hogg Foundation published a report titled “Understanding the Homeless” by Dr. Donald J. Baumann, Jr., a UT-based social psychologist, and Charles Grigsby, a social scientist at The Resource Group.[ii] The report uses Austin as a case study to assess the structural causes of homelessness, including:

- Deinstitutionalization with “inadequate provisions for community support.”

- Recessions.

- Rising costs of housing.

- “More restrictive eligibility requirements for welfare and disability benefits.”

- Substance use.

The discourse in Austin followed federal legislation, showing that researchers, service providers, and funders were already aware of the unhoused community and its struggles. While this report’s writers notice psychological factors like discouragement and “hopelessness” as “barriers to action,” they acknowledge that structural conditions exacerbate these hurdles (Baumann, p.27), such as:

- Assistance may be hard to access.

- Resources may have restrictive eligibility requirements.

- Shelters and other resources may be at capacity.

- Individuals may not know about the resources available to them.

- Criminalization exacerbates homelessness due to a lack of other resources.

- The public may want to “clear the streets” through sweeps (Baumann, pp. 28-29).

Solutions proposed include:

- Increasing outreach to unhoused communities through fliers.

- Mobile health services, and “key informants among the homeless.”

- Support groups for people transitioning out of homelessness.

- Supportive housing with formerly unhoused roommates.

- Waiving address requirements or other barriers for public services.

- A comprehensive “assessment and referral” system (Baumann, p. 31).

Despite its local focus, the report caught the attention of researchers and service providers—as well as people experiencing homelessness—nationwide, drawing in correspondence from as far away as California. These letters demonstrate the publication’s impact on its intended audience of philanthropists and service providers but also its resonance for communities across the nation. One unhoused person from the Valley Mayors’ Fund for the Homeless in Van Nuys, California wrote to request copies for distribution and affirm the report was “well written, very well researched and most sensible.” A service provider at the Challenge Foundation in Tarzana, California mentions that a client experiencing homelessness recommended the report to her.

As the landscape for people experiencing homelessness has changed, so too has the foundation’s work to support the mental wellness of individuals, including those experiencing homelessness. During the 2019 Legislative Session, Hogg policy staff testified in favor of supportive housing initiatives to set up unhoused individuals with a path to independent living and case managers. When Austin City Council voted to decriminalize homelessness and overturn the longstanding ban on public camping in 2019, then Mayor Steve Adler discussed this news with Hogg Foundation Communications Manager Imani “Ike” Evans in an episode of the Into the Fold podcast.

Homeless Policy in Austin

Though Austin has had a homeless population for decades, the number of unhoused people has risen dramatically as the cost of living has skyrocketed in recent years. Service providers recognize an especially large spike in homelessness since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, increasing most dramatically since the federal moratorium on evictions was struck down by the Supreme Court in 2021. Current estimates — which service providers believe to be undercounts — put Austin’s homeless population at well over 5,000 individuals. Moreover, the city calculates it would take upwards of $25 million just to provide temporary shelter beds to the unhoused community in town. This cost does not include other necessary services and resources.

In May 2021, Austin voters passed a ban on camping throughout much of Downtown and Central Austin called Proposition B. The ban instates fines of up to $500 for people found camping on this land. Since Proposition B, city and state officials have invested more resources into frequent “sweeps” of homeless encampments across town—including camps located in areas where taking shelter is permitted under Proposition B. Without sufficient shelter beds to house Austin’s homeless population even temporarily, individuals whose camps are swept have limited options of where to turn for assistance. Currently, the Supreme Court is hearing a case to determine whether cities with insufficient shelter beds, like Austin, can criminalize people experiencing homelessness for camping outside.

Amidst these changes, the unhoused community has found The Challenger Newspaper as a platform. The Challenger is a local publication written by and for unhoused individuals. In 2021, the news outlet was the recipient of Hogg Foundation special opportunity funds to support its operations and purchase tablets for unhoused contributors. The Challenger demonstrates that our unhoused neighbors are not just the subjects of academic reports but artists, creators, and agents of change.

For more information on this topic or to see the primary sources mentioned in this post, please reach out to our archivist at hogg-archives@austin.utexas.edu or check out the exhibit in the lobby of the Hogg Foundation office.

Related Links

- Austin’s New Approach to Homelessness and Well-Being

- Integrating Mental Health Care in the Medical Setting

[i] Bush, W. S. (2016). Circuit Riders for Mental Health: The Hogg Foundation in Twentieth-Century Texas. Texas A&M University Press.

[ii] Baumann, D. and Grigsby, C. (1988). [Understanding the Homeless: From Research to Action]. Hogg Foundation for Mental Health Archive (Special Topics, Filing Cabinet), Austin, TX, United States. https://archives.hogg.utexas.edu/jspui/handle/123456789/6083