There has been much discussion in health reform about using data to determine program effectiveness leading to improved population health. Questions like which programs work and which don’t, and which programs are making real impact, are being asked and answered through data to move us from usual treatment to effective treatment. Most agree that this effort is not about delivering more care but better care. Clearly, data is integral to making informed decisions to influence changes to policies, programs, and clinical practices in order to meet the whole health needs (physical health and behavioral health) of our communities across the nation. But there are lots of complexities to the data collection and data analysis issue.

Everyone is clamoring for data. I often hear: “We need more data!” Payors (e.g., government, health plans, and foundations) want data to determine effectiveness of programs being funded. Program administrators and managers want data to determine effectiveness and justification of programs being delivered. Providers want data to determine effectiveness of clinical services that go beyond the “usual treatment” (or “treatment as usual”), in order to justify paradigm shifts in traditional service delivery to more coordinated and integrated health care leading to improved health outcomes.

Policy makers, payors and regulators are using data to determine program effectiveness. Some pilots underway are examining how to phase out the current (and unsustainable) fee-for-service model of government-funded care and push the system towards financial bundled payment models and approaches that emphasize value-based care.

Those of us engaged in this dialogue have learned a few things that add to the complexity about the collection, interpretation, and use of data:

- Data collection simply for the sake of data collection is futile.

- Requiring the same data metrics from everyone doesn’t work well either. One size does not fit all. Not everyone wears a size 8 shoe. Metrics mandated or chosen from the top as program requirements are not always the best data points and may not be relevant in the real world.

- Data systems don’t talk to one another.

- Communities/health care recipients are often not included in these conversations.

Those of us in the health care sector think of ourselves as the experts and often make policy, program and practice decisions with the best intentions, but consumers/recipients of health care services are the true experts. They live with their health conditions day in and day out. They know what works. They can tell us what works, and what doesn’t.

Since data is integral to the conversation, how do we advance health reform and the use of data to make key decisions in policies, programs and clinical practices and as well as the future financing of health care? Some thoughts:

- Require meaningful quantitative and qualitative data: both are needed to tell the story of implementation successes and shortcomings. Both are equally important and an opportunity to learn what works as we test new models of care to determine impact and effectiveness (programmatic effectiveness and cost-effectiveness).

- Collect the right kind data. I refer to the notion of “right sizing” the data metrics required. Let’s agree to collect the right type of data needed to evaluate programmatic impact. If there is no real purpose for collecting specific and required data metrics, don’t collect it. Providers are already over-burdened to collect and report mounds of data as part of their reporting requirements. For payors/funders, that means stop requiring it. Novel idea.

- Data must be focused on outcomes and impact of services. Not just the number of encounters (outputs).

- EMR Interoperability enables better workflows and increases connectivity, and permits data transfer among EMR systems and health care stakeholders. Interoperable EMRs improve the delivery of health care by making the right data available in real time to the right people who need it immediately. Data can be more easily aggregated to assess population health outcomes, provider performance, and inefficiencies.

- Negotiated agreement between funders and providers on data points that make sense (relates to meaningful quantitative and qualitative data). Reimbursement (what services are paid for and under what conditions) must follow suit.

- And most importantly, communities and health care recipients must be engaged on health care, access to care, delivery of services, wellness, and recovery. Communities must be a part of the dialogue to define wellness: what are the outcomes they hope to achieve when seeking health care? Communities are capable of defining the goals, outcomes and solutions that matter to them regarding their health care.

We are in the midst of a seismic transformation of our health care system. That’s not a bad thing. That said, there is much at stake regarding the current and future financing of our health care system. Tomorrow’s health care system will look very different than the current system design wise; also how we finance health care will undoubtedly change. We need data to inform and drive our decisions and influence systemic change for the better. But we also need to re-evaluate the data we are currently collecting and ask, “Does this data truly inform us about access to and quality of services being delivered?” “Do the data sets help us understand program and cost impact and lead to improved health outcomes?” “Are we asking the right questions to the right people (providers and service recipients) who can better inform this process?”

I’ll say it again; data is integral to this conversation. Good data. The right data. Without it, we won’t know the true impact of the countless programs and $3.0 trillion or $9,523 per person spent today on health care (2014 National Health Expenditure Accounts).

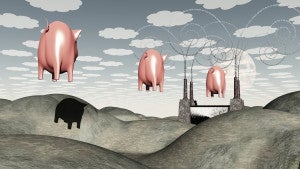

Everyone believes they operate or fund a great program. But even if you can get pigs to fly, it doesn’t count if you don’t measure it!