Artist: Emily Flake. All rights reserved.

This post was co-authored with Neely Myers, PhD.

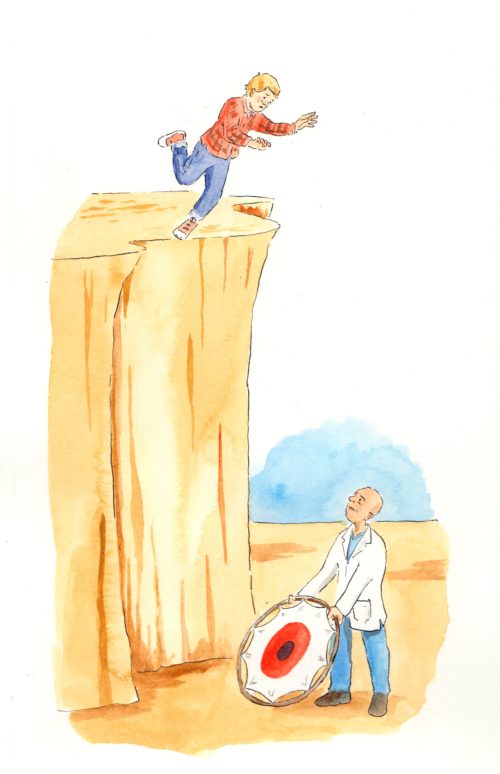

The mental health care system is failing young adults who are struggling with the onset of psychosis, the very time when effective help could make a difference.

This failure has implications not just for the care of the affected youth. Psychosis is one of the few mental health conditions that if left unchecked can potentially increase the likelihood of violent behavior. Take the stark example of James Holmes, the Aurora, Colorado movie theater shooter, who was later diagnosed as having been psychotic.

Holmes even called a mental health hotline just before the shooting. No one answered.

Certainly, we could offer much more appealing, effective and higher-quality care if we tried.

In the last decade, increasing research suggests psychosis may be similar to cancer in that it occurs in progressive stages, starting with symptoms that can progress into a disorder if not addressed effectively. Psychotic disorders, like schizophrenia, cause people to experience extremely distorted realities, often in the form of hallucinations and delusions. They are also accompanied by more discrete symptoms such as disorganized thinking, low motivation, poor eye contact, or neurocognitive issues such as poor working memory.

However, as the NIMH-funded Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode project has documented, if “recovery-oriented care’ is offered and accepted at an early stage it may set the groundwork for recovery. Many who have experienced recovery discover an even richer and more fulfilling life than the one they were living before the onset of symptoms.

Initial psychosis often strikes when someone is between 15 and 30 years old, which is already a particularly stressful time as young people make a transition to adulthood.

In most cases, the mental health system fails to address these fundamental needs and stresses, and instead acts in ways that perpetuate the problem.

Many young adults are first introduced to the mental health system after being escorted by police, forcibly hospitalized and given little explanation of what’s happening. They’re often prescribed strong pharmaceuticals at higher doses, which can leave those who take them feeling sluggish and alien to themselves. The medications can also lead to serious weight gain. And good programs are rarely in place to educate and incorporate family members into any kind of family healing process in a holistic way, which is often needed.

Both of us have worked with young adults experiencing psychosis and it’s not surprising to us that so many of them say they want to get as far away from mental health services and treatment as possible. Many then drop out of care precisely when it’s most critical.

So what should we do?

A number of programs — OPUS in Denmark, TIPS in Norway, EPPIC in Australia, and the STEP program in Connecticut, for example — offer targeted, effective care that is youth-oriented.

These programs offer a few common things: symptom-management techniques such as cognitive behavioral therapy, low-dose medications, and support for career and educational goals. They work with families to initiate therapy or education and incorporate them early on into the treatment team. They also teach them about symptoms, services and treatment options, and help troubleshoot issues as they arise.

We need more programs like this in the United States, and they need to be universally available, affordable, and attractive to youth. It’s not an impossible task. But until we make system-wide changes to the mental health care system in this country, we are all complicit in perpetuating psychosis among America’s youth. Helping affected youth is an ethical imperative.

During James Holmes’ trial, his mother Arlene Holmes testified that if she had known what he’d been going through, “We wouldn’t be sitting here … I would have been crawling on all fours to get to him.” She continued, “None of this would have happened.”

She likely would not have been able to stop everything herself. But if the best possible system of care and support had been in place, things may have been different — for Holmes, his family, his victims, and all of us. We cannot change the past, but if we use what we know and put funding behind it, we may help keep it from happening again in the future.

Neely Myers, PhD, is an assistant professor of anthropology at Southern Methodist University. She is the author of Recovery’s Edge: An Ethnography of Mental Health Care and Moral Agency, published by Vanderbilt University Press.