This piece was co-authored with Dr. William S. Bush, author of Circuit Riders for Mental Health: The Hogg Foundation and the Transformation of Mental Health in Texas. It originally ran in the Austin American-Statesman and our blog on the Huffington Post.

The Texas Tribune kicked off Mental Health Month by highlighting a public health emergency; in fact, a public health crisis. A shortage of available beds in the state’s system of psychiatric hospitals has left nearly 400 Texans languishing for months, sometimes years, on a waiting list. The Tribune describes examples of individuals who wound up accessing care only after being charged with a crime. Over half of the current residents in Texas’ psychiatric hospitals are “forensic” commitments through the criminal justice system, often the only way that low-income people with mental illness can access treatment. Further compounding these daunting problems is the continued use of “crumbling, century-old state hospitals” built in an earlier time when mental health and mental illness were poorly understood even by credentialed experts.

The Texas Tribune kicked off Mental Health Month by highlighting a public health emergency; in fact, a public health crisis. A shortage of available beds in the state’s system of psychiatric hospitals has left nearly 400 Texans languishing for months, sometimes years, on a waiting list. The Tribune describes examples of individuals who wound up accessing care only after being charged with a crime. Over half of the current residents in Texas’ psychiatric hospitals are “forensic” commitments through the criminal justice system, often the only way that low-income people with mental illness can access treatment. Further compounding these daunting problems is the continued use of “crumbling, century-old state hospitals” built in an earlier time when mental health and mental illness were poorly understood even by credentialed experts.

This depressing state of affairs recalls an earlier period, in the decade after World War Two, when similar conditions sparked a mass movement that decried inadequate mental health care as “the shame of Texas.”

In that era, a generation of mental health reformers, some of whom were military veterans, confronted a system of seven state hospitals that were overcrowded, unsanitary, prison-like, and poorly staffed. William Menninger, the first psychiatrist to achieve the rank of Brigadier General during the war, advocated for more robust community mental health services. Popular films such as The Snake Pit (1948) dramatized the plight of patients trapped in overcrowded and prison-like hospitals, while the federal government inaugurated the National Institute for Mental Health in 1946 to support non-institutional programs.

Meanwhile, in Texas, reformers led by the Hogg Foundation for Mental Health launched a decade-long campaign to reform the state’s hospitals. In the spring of 1949, nearly every major Texas newspaper ran an eight-part series entitled “The Shame of Texas,” written by a young veteran and University of Texas student named John Porter. In gruesome detail, Porter made the case that Texas housed “the nation’s worst hospitals,” a viewpoint echoed in subsequent reports by the United States Public Health Service and the American Psychiatric Association.

Meanwhile, in Texas, reformers led by the Hogg Foundation for Mental Health launched a decade-long campaign to reform the state’s hospitals. In the spring of 1949, nearly every major Texas newspaper ran an eight-part series entitled “The Shame of Texas,” written by a young veteran and University of Texas student named John Porter. In gruesome detail, Porter made the case that Texas housed “the nation’s worst hospitals,” a viewpoint echoed in subsequent reports by the United States Public Health Service and the American Psychiatric Association.

Throughout much of the 1950s, Texas ranked at or near the bottom in per-patient spending on mental health care.

Of equal concern to reformers was the overuse of the criminal justice system in hospital commitments. Texas was one of only two states that required a jury trial for all psychiatric commitments, which meant that even non-criminal cases passed through an often traumatic criminal court process. One particularly negative consequence of this system transformed county jails into de facto “holding pens” for people with mental illness awaiting an opening in the state’s overcrowded psychiatric hospitals.

Of equal concern to reformers was the overuse of the criminal justice system in hospital commitments. Texas was one of only two states that required a jury trial for all psychiatric commitments, which meant that even non-criminal cases passed through an often traumatic criminal court process. One particularly negative consequence of this system transformed county jails into de facto “holding pens” for people with mental illness awaiting an opening in the state’s overcrowded psychiatric hospitals.

Attempts to remedy these deplorable conditions met with only partial success during much of the 1950s, even as a popular movement sprang to life. Civic groups led by the Texas Society for Mental Hygiene and the Texas Jaycees mounted letter writing campaigns, led caravans of visitors to the state’s hospitals, and circulated photographs of what they saw.

Journalists continued to publish graphic exposes. The Hogg Foundation released a powerful documentary film, “In a Strange Land,” that was shot at Terrell Hills State Hospital, one of five older hospitals still in use today that the Texas Department of Health Services has deemed “beyond repair.” Elected officials, led by Governor Allen Shivers, managed to make some modest improvements, but met with limited political support, much to their frustration. The reasons then were the same as they are now: too often out of sight and out of mind, people with mental illness struggle to garner sustained public interest. As Robert Sutherland, the Hogg Foundation’s first director, once observed, people with mental illness “have no alumni groups to wage a campaign for improvement.”

Journalists continued to publish graphic exposes. The Hogg Foundation released a powerful documentary film, “In a Strange Land,” that was shot at Terrell Hills State Hospital, one of five older hospitals still in use today that the Texas Department of Health Services has deemed “beyond repair.” Elected officials, led by Governor Allen Shivers, managed to make some modest improvements, but met with limited political support, much to their frustration. The reasons then were the same as they are now: too often out of sight and out of mind, people with mental illness struggle to garner sustained public interest. As Robert Sutherland, the Hogg Foundation’s first director, once observed, people with mental illness “have no alumni groups to wage a campaign for improvement.”

But it’s not enough. There are still huge waiting lists for community-based mental health services. The criminal justice system, through the forensic commitment system, remains the only gateway to treatment for far too many people. Our state mental hospitals are crumbling, with the Department of State Health Services estimating that replacing or renovating aging state hospitals will cost taxpayers over $1 billion.

But it’s not enough. There are still huge waiting lists for community-based mental health services. The criminal justice system, through the forensic commitment system, remains the only gateway to treatment for far too many people. Our state mental hospitals are crumbling, with the Department of State Health Services estimating that replacing or renovating aging state hospitals will cost taxpayers over $1 billion.

Then there are the workforce issues. The usual problems of the social services sector—high staff turnover, low pay, recruitment – would be daunting enough on their own. Challenges unique to Texas – the need for culturally and linguistically competent service providers, and the sheer number of underserved communities in our sprawling state—make the mental health workforce shortage that much more painfully felt.

So, what can be done? For starters, let’s continue to build upon the improvements of the last few years. We must fully implement and improve integrated health care, recognizing that transformation of health care takes time. Effective integrated health care is the comprehensive coordination of mental health, substance use, and primary care services. The integration of primary care and behavioral health services allows health professionals to better coordinate treatments for the benefit of all of our communities.

We also need to improve the mental health reimbursement rates. Only half of Texas psychiatrists accept private insurance, compared with nearly 90 percent of other physician types. And only 21 percent of Texas psychiatrists will accept Medicaid patients, according to the Texas Medical Association. The state should increase reimbursement rates to increase the number of practicing mental health care providers willing to provide services to consumers with Medicaid.

The state would also be wise to increase access to services provided by Certified Peer Specialists where “peers,” who have a history of lived experience with mental illness or substance use, rely on their personal recovery and specialized training to help guide other individuals experiencing a behavioral health condition in their own recovery.

Additionally, we need to expand the use of technology. Technology, such as telehealth and telepsychiatry, can be useful to support individuals in rural areas of our state that have significant mental health professional shortages.

So, meet with your local city and county officials and state representatives. Take part in the whirlwind of public debate and policymaking during the upcoming legislative session. Bring these issues and facts to their attention. Emphasize that our loved ones are being treated in crumbling institutions. That where community-based services exist, they are underfunded. That we the people (ourselves, our families, and our neighbors) are at the mercy of an overstretched workforce in which the availability of competent service providers is too often a matter of geographical accident – living in proximity to an urban center and even then we still have access challenges. Where if all else fails, the criminal justice system picks up the pieces; and too many of our veterans and loved ones are ending up homeless, marginalized, and unseen. For if we do not do enough, one thing is certain: the shame of Texas will continue.

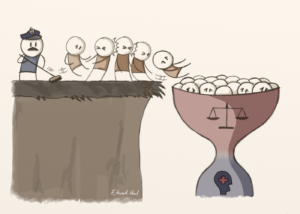

The accompanying illustrations are by Edward Howl, a UK-based cartoonist and blogger. For background on our use of illustrations for op-eds, check out this blog post.