This is part of our Legislative Series, which explores our policy priorities. Check out the other episodes in this series on first episode psychosis and mental health and housing.

“All individuals should be included when we discuss community well-being and wellness,” Shannon Hoffman says. “All individuals—whether they’re using substances, if not more so—should be included in that conversation.”

In October 2017, the month that the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) declared the opioid crisis a public health emergency, Speaker of the Texas House of Representatives Joe Straus created the House Select Committee on Opioid and Substance Abuse.

In October 2017, the month that the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) declared the opioid crisis a public health emergency, Speaker of the Texas House of Representatives Joe Straus created the House Select Committee on Opioid and Substance Abuse.

Tasked with devising recommendations for legislative action on opioid deaths and other substance use issues, the select committee met regularly before publishing an interim report last November that encapsulated months of research, discussion and testimonial hearings. Even though the opioid crisis hasn’t hit Texas as hard as other parts of the country, the report finds, opioid overdoses still claimed 3,000 lives across the state in 2017—and have increased by about ten percent each year since 2014.

Given that more than two million Texans experience substance use disorders, the recommendations of the select committee are a welcome contribution to a broader conversation about the intersection of public health and public policy—particularly when the endgame is systems-level change. On this episode of our Into the Fold podcast, Hogg Foundation policy fellow Shannon Hoffman, an expert on substance use policy, elaborates on the report’s findings.

Harm Reduction: An Evidence-Based Response to Substance Use

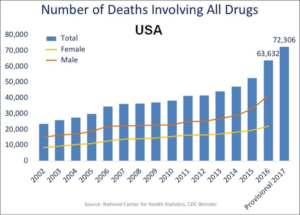

Glance through the interim report, and one thing becomes startlingly clear: as Hoffman puts it, “the numbers are pretty staggering.” They cut across multiple sectors and systems of care, demonstrating just how costly, pervasive and multifaceted substance use disorders can be—for the individual and communities at large. In Texas, the health care costs of opioid abuse topped 1.9 billion dollars between 2005 and 2014. Within the same timeframe, drug-related emergency room visits increased a full 99 percent—meaning demands on the capacity of first responders and health workers surged, too.

“Often substance use is treated in the most expensive and least appropriate settings,” Hoffman says. Insufficient quantities of providers or programs, gaps in insurance coverage, and inadequate training of law enforcement and mental health professionals all contribute to the systemic breakdowns that keep individuals from getting the services they need. Misinformation and misconceptions about the nature of substance use disorders also play a role.

One solution is to build up harm reduction, which the Harm Reduction Coalition defines as “a set of practical strategies and ideas aimed at reducing negative consequences associated with drug use.” By incorporating a spectrum of services designed to meet individuals “where they’re at”—whether that means allowing the exchange of needles to prevent communicable disease, or enrollment in an abstinence program—harm reduction lays emphasis on “a belief in, and respect for, the rights of people who use drugs.”

What harm reduction doesn’t do is condone drug use. “It’s understanding someone’s battling a fight—potentially for their lives,” Hoffman says, “and if there’s a solution to potentially ease some of that battle and, in turn, help their community, why not?”

Cause for Hope: Substance Use Policy in Texas

As of now, Texas is one of ten states that doesn’t offer syringe service programs, an example of comprehensive harm reduction services. Texas also lacks Good Samaritan laws, which provide basic legal protections to those who call 911 in the event of a drug overdose and thus eliminate the fear of incarceration that might keep someone from doing so.

Harm reduction initiatives and Good Samaritan laws are included in the select committee’s recommendations—a milestone in its own right. Alongside them are other “especially significant” preventative measures for use and overuse, such as increasing the availability of overdose reversal drug Naloxone, providing education and evidence-based prevention programs in middle schools and high schools, and developing pre-arrest diversion strategies.

“I think as individuals learn more about and become familiar with a public health approach to substance use,” Hoffman says, “they’re more inclined to be open to the solutions and ideas that not only aim to treat people with humanity and empathy—even if they’re using substances—but, in turn, can make their community safer and healthier.”

“I have hope,” Hoffman concludes, “and I’m optimistic that we’re moving in a more understanding direction.”

Recommended Resources:

- Texas Mental Health Guide

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA)

- Texas Public Policy Foundation

Learn more about our podcast and check out other episodes!