Policy Concerns

- Diverting people with mental illness who commit low-level offenses away from correctional facilities and into treatment settings

- Expanding training for jailers and correctional staff on mental health issues and de-escalation techniques

- Improving mental health screening, safety, and suicide prevention procedures in correctional settings

- Decreasing the use of prolonged solitary confinement, repeated restraints, and other aversive interventions on persons incarcerated with mental illness

- Increasing external oversight within prisons, jails, and other incarceration settings to ensure that persons with mental illness experience constitutional and humane conditions of confinement

- Improving access to jail diversion opportunities and a full range of psychiatric medications, especially within rural jail facilities

- Increasing access to intensive support services as individuals with mental illness transition from jail or prison into the community, including jail in-reach programs, forensic assertive community treatment (FACT) teams, and reentry peer support

Fast Facts

- Studies estimate that over half of all adults who are incarcerated in U.S. prisons and jails have at least one mental health condition.

- On May 31, 2016, there were 146,746 people incarcerated in Texas prisons, which accounted for 98% of TDCJ’s operating capacity.

- In FY 2014, the average cost for an adult in a Texas prison was $54.89 per day. In contrast, adults on parole cost $4.04 per day, and adults under community supervision (formerly called adult probation) cost $3.20 per day.

- The average daily cost per person who requires medical care in Texas prisons is between $96 and $104, while the average daily cost per person in a psychiatric correctional facility is $145.

- On June 1, 2016, Texas county jails collectively operated at 70.5% capacity with a total jail population of 65,793.

- In FY 2015, about one million people cycled through local jails in Texas.

- In 2015, 50% of grievances submitted by incarcerated people to the Texas Commission on Jail Standards (TCJS) involved complaints regarding medical services, including mental health services.

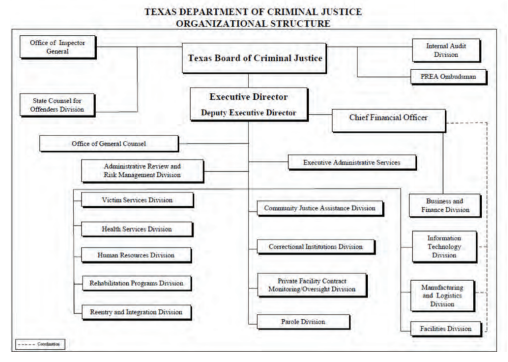

Organizational Chart

Source: Texas Department of Criminal Justice. (n.d.). Organizational Charts: Texas Department of Criminal Justice.

Texas Department of Criminal Justice and Local Criminal Justice Agencies

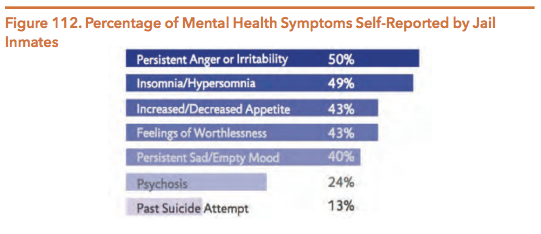

A significant number of individuals involved in the Texas criminal justice system live with one or more mental health conditions, and many have co-occurring substance use disorders. The strong connection between mental health and the criminal justice system has not always existed. In the 1970s, only 5% of incarcerated persons in the U.S. had a serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Almost 50 years later, studies estimate that 15% to 24% of incarcerated persons have a serious mental illness. In 2015, about 30% of people in local Texas jails had at least one serious mental illness. The percentage of justice-involved individuals with less severe mental health issues, such as mild depression, is even greater; researchers estimate that over half of people incarcerated in U.S. prisons and jails have at least one mental health problem. Figure 112 demonstrates that a large proportion of individuals in jails across the country self-report at least one mental health symptom.

Source: As used in Hautala, M. (2015). In the Shadow of Sandra Bland: The Importance of Mental Health Screening in U.S. Jails. Texas Journal on Civil Rights & Civil Liberties, 21(1), 98. Data derived from Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2006). Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates. 2.

Despite the overrepresentation of people with mental illness in U.S. prisons and jails, research suggests that only 7% of these individuals enter the criminal justice system because of behavior linked directly to their mental illness. Instead, their alleged criminal behaviors are often tied to behavioral factors (such as hostility, disinhibition, or emotional reactivity) or to social factors (such as poverty and homelessness).

The extent to which serious mental illness is connected to dangerous behavior is unclear. In some cases, it seems that mental illness may be linked to violent behavior, but research shows that this link is weak. In fact, people with mental illness only commit an estimated 4% of violence in the U.S. Contrary to the fear created by highly publicized shootings and the discussions of mental illness that often follow, persons with serious mental illness commit a small proportion of homicides in which a gun is used. The vast majority of people with a diagnosable serious mental illness never engage in any violent activities. Statistical evidence shows that, in the absence of a substance use disorder, most mental illnesses are unrelated to acts of violence. Unfortunately, the science of risk assessment has not advanced sufficiently to allow researchers to identify which individuals will commit violent acts. Psychiatrists can rule out who is not going to be violent better than they can identify who will be violent.

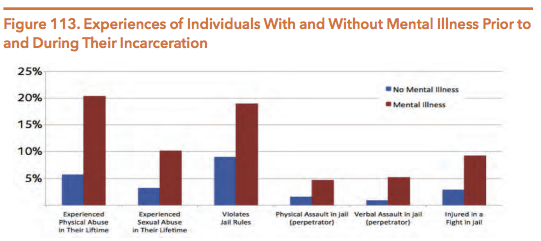

Prior to their imprisonment, justice-involved persons with mental illness are more likely than incarcerated persons without mental illness to have used drugs, experienced homelessness, or survived abuse. Once incarcerated, they also tend to face challenges that can worsen their mental health conditions. People with mental illness are more likely than other incarcerated populations to experience physical abuse, solitary confinement, and sexual victimization. All of these experiences can exacerbate preexisting diagnoses. Figure 113 demonstrates some of the challenges that people with mental illness disproportionally face prior to and during their incarceration. In addition to individual mental health impacts, the growing number of people with serious mental illness in the justice system raises important challenges concerning correctional facility management, unit security, and state and county budgets.

Source: As used in Hautala, M. (2015). In the Shadow of Sandra Bland: The Importance of Mental Health Screening in U.S. Jails. Texas Journal on Civil Rights & Civil Liberties, 21(1), 102. Data derived from Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2006). Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates. 4, 10.

Changing Environment

Across the nation, Texas serves as a model for criminal justice reform. In 2007, the 80th Texas Legislature altered the trajectory of criminal justice policy by prioritizing diversion from incarceration over the construction of new prisons. In 2015, legislators continued that trend. Lawmakers passed legislation to enhance the detection of mental illness, increase diversion opportunities, and improve the reentry process. For their work, Senator Whitmire (D-Houston), Senator Ellis (D-Houston), and Representative McClendon (D-San Antonio) received the Dallas Morning News’ Texans of the Year title. Together, these legislators worked with other senators and representatives across the political aisle to pass reforms that are projected to cut costs, decrease incarceration rates, and better serve persons with mental illness.

The major legislation and budget riders related to mental illness and adult criminal justice passed in 2015 are explained below. Legislation is described in the order by which an individual with mental illness may experience the Texas criminal justice system. Information in this section is not a comprehensive account of the mental health and criminal justice-related legislation passed during the 84th legislative session.

It should be noted that the Texas Legislature’s 2015 reforms will be implemented under new TDCJ leadership. In April 2016, Brad Livingston, TDCJ’s executive director who served the agency for 12 years, announced his retirement. In June, the Texas Board of Criminal Justice selected TDCJ’s deputy executive director, Bryan Collier, to serve as the agency’s new executive director. Collier has worked for TDCJ in various line staff and management positions for over 30 years.

MAJOR LEGISLATION FROM THE 84TH TEXAS LEGISLATURE

HB 1338: Training for Peace Officers and First Responders on Brain Trauma

In 2015, Texas legislators passed HB 1338 (84th, Naishtat/Menendez) to improve the detection of brain injury and mental illness at the first stage of the criminal justice process – encounters with law enforcement officers. HB 1338 requires the Texas Commission on Law Enforcement to partner with the HHSC Office of Acquired Brain Injury and the Texas Traumatic Brain Injury Advisory Council to design training for peace officers and first responders regarding persons affected by brain trauma. The training must incorporate information on the direct effects of acquired brain injury and traumatic brain injury, which can include major depression, bipolar affective disorder, and anxiety disorders. The training curriculum is meant to improve encounters between first responders and individuals with brain injuries, particularly veterans. HB 1338 presents an opportunity to detect mental illness and divert individuals from involvement in the criminal justice system before they are arrested and booked into a local jail.

SB 1507: Statewide Coordination and Oversight of Forensic Mental Health Services

Between 2001 and 2016, the number of forensic commitments to Texas state hospitals more than tripled. Forensic commitments involve individuals with mental illness who have been arrested for a crime and subsequently admitted to a state hospital because they are deemed incompetent to stand trial or not guilty by reason of insanity. In 2015, legislators passed SB 1507 (84th, Garcia/Naishtat) to expand upon past efforts to address the growing forensic population. The bill required DSHS to appoint a statewide forensic director in order to improve the coordination and oversight of forensic mental health services. The bill also specified that the forensic director must work with a group of experts and stakeholders to develop recommendations for improved forensic service coordination. The workgroup includes representatives from HHSC, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ), the Texas Juvenile Justice Department (TJJD), local mental health authorities (LMHAs), and other agencies involved in the social, health, and legal aspects of forensic services. For more on SB 1507 and forensic services in general, see the HHSC and DSHS sections of this guide.

HB 1083: Mental Health Assessments for Individuals in Administrative Segregation

Individuals with mental illness who serve time in Texas prisons and jails are disproportionately housed in solitary confinement (known in Texas as administrative segregation or “ad seg”). Psychological research shows that placement in ad seg can both cause and exacerbate mental health issues, such as anxiety, depression, paranoia, and self-harm. In 2016, about 32% of people confined in ad seg were also on TDCJ’s mental health caseload. Legislators passed HB 1083 (84th, Marquez/Whitmire) to improve health outcomes for individuals with mental illness who are confined in ad seg units. The bill requires a medical or mental health professional to perform a mental health assessment for incarcerated individuals before they are confined in ad seg. If the assessment determines that ad seg is inappropriate for the person’s mental or physical health condition, TDCJ must assign the individual to a different housing unit. For example, in 2014, TDCJ began a mental health diversion pilot program at the Hughes Unit for individuals who require separation from the general population but for whom ad seg is clinically inappropriate. Equipped with 420 beds, the six-month program allows participants to engage in group therapy and meet with on-site mental health professionals before “graduating” and integrating back into the general prison population. During the summer of 2016, TDCJ will expand the program to include 420 additional beds at the Michael Unit. The goal is to divert all 1,500 individuals in solitary confinement who are also on TDCJ’s mental health caseload away from ad seg units and into more therapeutic environments.

SB 578: Providing Incarcerated Individuals with Reentry and Reintegration Information

About 95% of incarcerated individuals are released back into their communities, but this transition can be challenging for many. Formerly incarcerated people face stigma and institutional barriers upon release, which increases the likelihood that they will cycle back through the criminal justice system. To ease the reentry process, Texas lawmakers passed SB 578 (84th, Hinojosa/Allen). The bill requires TDCJ to collaborate with nonprofits, faith-based organizations, and other criminal justice-focused groups in the development of reentry resource packets for people who are about to be released from incarceration. The packets must include county-specific information about emergency assistance programs, workforce offices, housing options, counseling services, and other relevant resources that can improve the reentry process and decrease recidivism. TDCJ is required to make the reentry packets available to individuals 180 days before their release.

RELEVANT RIDERS

Legislators also addressed criminal justice and mental health-related issues through riders to the Department of State Health Services (DSHS) budget (HB 1, Art. II). Relevant riders are listed below.

- Rider 35 required DSHS and community mental health centers to identify individuals with mental illness in the justice system and report prevalence data on this target population.

- Rider 61 appropriated approximately $32 million in general revenue funds to expand Medicaid state plan services in order to divert individuals away from jails and emergency rooms and into community-based treatment programs.

- Rider 66 required DSHS to allocate $5 million in both FY 2016 and FY 2017 to the Harris County Jail Diversion Pilot Program. The 83rd Texas Legislature created the program in 2013 through SB 1185 (83rd, Huffman/Schwertner). For more information on the program, Harris County Jail Diversion Pilot Program later in this chapter of the guide.

- Rider 70 appropriated about $1.7 million per year in general revenue funds for FY 2016 and FY 2017 to implement a jail-based competency restoration pilot program for individuals who would otherwise be transferred from a jail to a mental health facility. The 83rd Legislature created the pilot program in 2013 through SB 1475 (83rd, Duncan/Zerwas). For more information on the program, see the DSHS chapter of this guide.

- Rider 73 appropriated $1 million in general revenue funds for FY 2016 and FY 2017 to implement a peer support reentry pilot program. For more information on the program, see Reentry Peer Support section in this chapter of the guide.

SANDRA BLAND AND JAIL SAFETY CONCERNS

After the 84th legislative session concluded, the Texas criminal justice system was brought into the national media spotlight. In July 2015, 28-year-old Sandra Bland was pulled over after failing to use her turn signal when changing lanes. Her confrontation with a state trooper led to her arrest and booking at a Waller County jail where Bland could not afford to post bail. Three days later, Bland was found dead in her cell by apparent suicide. The controversy highlighted the risks that aggressive arrest procedures and money bail practices pose for people with mental illness. Bland’s death also demonstrated the need for improved mental health screening procedures and increased adherence to jail safety standards within incarceration settings.

In response to Bland’s death, the House Committee on County Affairs and the Senate Criminal Justice Committee convened interim hearings to discuss the state’s jail standards. The Texas Senate received an interim charge to evaluate jail safety guidelines and review law enforcement and correctional officer training as it relates to individuals with mental illness. Finally, House Speaker Joe Straus appointed representatives to the House Select Committee on Mental Health; Speaker Straus formed the committee to examine the Texas behavioral health system, including the disproportionate incarceration of persons with mental illness in Texas jails and prisons.

Overview of the Texas Criminal Justice System

Individuals involved in the criminal justice system may be placed in a variety of settings. Local jails operated by counties or municipalities hold defendants who are awaiting trial and people who have been convicted of low-level crimes. In January 2016, about 63% of people held in Texas county jails had not been convicted of a crime and were awaiting trial. While county sheriffs manage local jails, the Texas Commission on Jail Standards (TCJS) acts as the external regulatory agency for all county jails and seven privately-operated municipal jails. By setting jail standards and inspecting county jail facilities, TCJS assists local governments in providing safe and constitutional conditions of confinement for individuals who are detained across Texas. However, TCJS does not provide oversight within city-operated municipal jails. Instead, the municipal jails located in Texas are not regulated by any external agencies, though individuals, including those with mental illness, may be confined here for extended periods of time.

In contrast, state-operated facilities, such as state jails and prisons, hold individuals who are convicted of more serious offenses. TDCJ operates these facilities and oversees contracts with private correctional agencies. Unlike county jails, an external oversight body does not monitor Texas prisons and state jails. In previous legislative sessions, however, advocates have introduced legislation to create such a body.

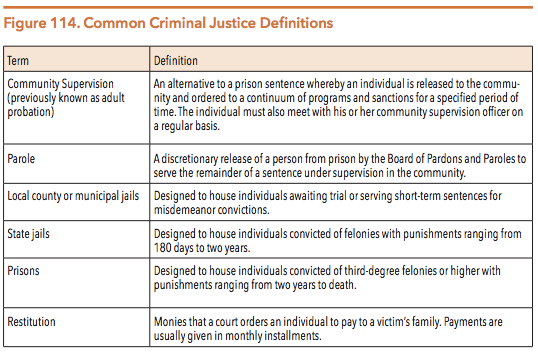

Figure 114 contains a glossary of terms typically used in the criminal justice system.

Source: Harris County Community Supervision & Corrections Department. (n.d.). Frequently Asked Questions.

Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics. (n.d.). Terms and Definitions: Corrections.

People receiving public behavioral health services make up a sizeable portion of the total population of justice-involved persons in Texas. In 2016, the HHSC estimated that 37% of individuals in Texas prisons had contact with the public mental health system prior to their incarceration. These incarcerated persons tend to experience greater functional impairments from mental illness, more housing instability, and less family and community support than other incarcerated groups.

During the 80th legislative session, Texas policymakers adopted a new way to identify justice-involved individuals with behavioral health needs. Legislators passed SB 839 (80th, Duncan/Madden), which required DSHS and DPS to replace a 72-hour manual data exchange process with a real-time identification system for incarcerated persons with special needs. When individuals are booked at a county jail, correctional officers must now check each person’s information against the DSHS Clinical Management for Behavioral Health Services (CMBHS) database. The process, known as a Continuity of Care Query (CCQ), instantly tells jail employees if a particular person has been hospitalized in a state psychiatric facility or if the person has experienced an encounter, authorization, or assessment by a local mental health authority (LMHA) within the past three years. If a match is detected, the jail then contacts the relevant LMHA in order to link the individual to available community resources.

Between September 2014 and August 2015, 234 counties in Texas initiated 991,073 CCQ match requests for adults. About 7% (73,844) of the queries were exact matches with information maintained in the DSHS mental health database, and about 37% (369,013) were probable matches. Both exact and probable matches alert the local jails and LMHAs to exchange pertinent information.

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice

TDCJ’s mission is to “provide public safety, promote positive change in offender behavior, reintegrate offenders into society, and assist victims of crime.” In addition to confining convicted individuals, TDCJ manages community-based jail diversion programs and oversees individuals on community supervision and parole. TDCJ is responsible for providing health services, including behavioral health services, to people who are convicted and sentenced to state jails, state prisons, and private correctional facilities that contract with TDCJ. The Correctional Managed Health Care Committee (CMHCC) develops statewide policies regarding correctional health care services and coordinates the delivery of those services to persons in the TDCJ system. This committee is made up of nine voting members, including a TDCJ representative, medical doctors, and mental health professionals, and one non-voting member who is appointed by the Texas Medicaid director.

Cost and Funding Summary

On May 31, 2016, there were 146,746 individuals incarcerated in Texas prisons. The average cost of incarcerating an individual in a state facility was $54.89 per day in 2014. In contrast, individuals on parole cost was $4.04 per day, and individuals on community supervision cost $3.20 per day.

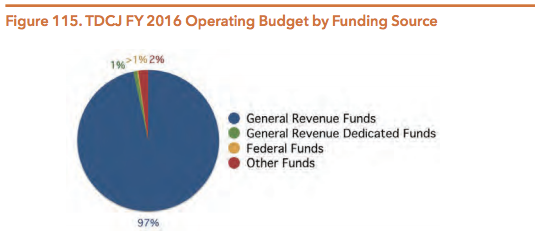

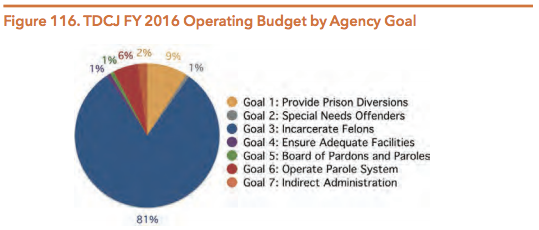

The TDCJ operating budget for FY 2016 was $3,406,167,380. Figure 115 breaks down TDCJ’s budget by funding source, and Figure 116 breaks down the budget by agency goal.

Source: Texas Department of Criminal Justice. (2015, December 1). Operating Budget for Fiscal Year 2016 Submitted to the Governor’s Office of Budget, Planning and Policy and the Legislative Budget Board. 6. Note: The “Other Funds” category includes interagency contracts, appropriated receipts, and general obligation bond proceeds.

Source: Texas Department of Criminal Justice. (2015, December 1). Operating Budget for Fiscal Year 2016 Submitted to the Governor’s Office of Budget, Planning and Policy and the Legislative Budget Board. 1-2.

The 84th Texas Legislature appropriated about $247.9 million in both FY 2016 and FY 2017 for the provision of behavioral health and substance use services within TDCJ. In 2015, legislators also created the Statewide Behavioral Health Coordinating Council comprised of 18 state agencies, including TDCJ, to develop a five-year strategic plan and expenditure proposal (See HHSC section). The plan and proposal will help agency leaders determine how behavioral health funds can be spent most efficiently and effectively across the state.

TDCJ Facilities and Housing Issues

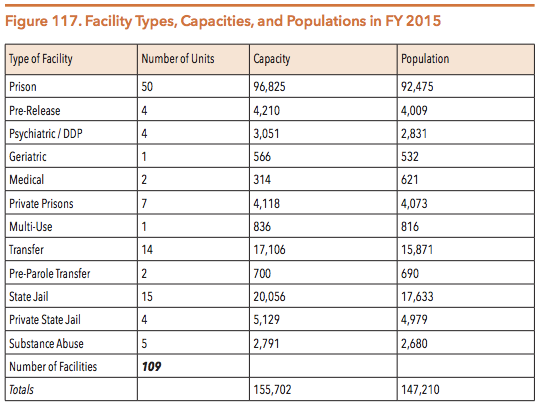

TDCJ has a number of facilities located throughout the state and has headquarters in both Austin and Huntsville. Figure 117 below depicts TDCJ’s population distribution and capacity by type of facility.

Source: Texas Department of Criminal Justice. (2016, April). Data request: TDCJ facility statistics.

A complete list and map of TDCJ facilities is available.

ADMINISTRATIVE SEGREGATION

Incarceration in TDCJ facilities can have a serious impact on an individual’s mental health. People confined in isolation are at even greater risk for mental health deterioration. These individuals are up to eight times more likely than those in the general prison population to engage in self-harm and nine times more likely to commit suicide. In a 2015 study, the ACLU of Texas and the Texas Civil Rights Project reported that TDCJ holds 4.4% of its incarcerated population in solitary confinement – a proportion that is four times greater than the national average. People with mental health conditions are overrepresented in the population of segregated inmates. In 2014, about 30% of TDCJ’s isolated population was identified as having some form of mental illness treatable by outpatient care.

TDCJ utilizes two types of solitary confinement for varying lengths of time. First, correctional officers use short-term disciplinary segregation for punitive purposes. Second, TDJC uses administrative segregation to house inmates for an indefinite period of time when they are considered dangerous to themselves or others. Both types of segregation involve holding individuals in a small, isolated cell for about 22 hours per day. On average, TDCJ inmates remain in isolation for almost four years, but in 2015, ten TDCJ inmates reached 30 consecutive years in administrative segregation. Individuals confined in isolation for even short spans of time can experience negative mental health outcomes, including major depression, cognitive disturbances, psychosis, and suicidal ideation.

Despite these adverse mental health outcomes, individuals can be released directly from administrative segregation into the community. Termed “flat release,” this practice occurs when incarcerated individuals finish their prison sentences while they are housed in ad seg, causing TDCJ to release them directly from the most restrictive prison environment (i.e., isolation) to the streets without supervision or support. Research shows that flat release is linked to higher recidivism rates, which places both formerly incarcerated individuals and their fellow community members at risk.

In recent years, TDCJ leaders and state legislators have taken steps to decrease the use of flat release in Texas. In 2012, TDCJ created the Ad Seg Pre-Release Program (ASPP) which uses cognitive behavioral interventions and group recreation to improve each participant’s reentry process; a total of 476 individuals completed the transitional program in FY 2014. TDCJ then created the Administrative Segregation Therapeutic Diversion Program (ASTDP) in 2014 to better connect segregated inmates with mental health services and improve their future behavioral and recidivism outcomes. By the end of 2016, 840 beds at the Hughes and Michael Units will be available for ASTDP participants. In addition to these reform initiatives, the Senate Committee on Criminal Justice and House Committee on Corrections also received interim charges during the 2016 interim session to review reentry opportunities for individuals housed in administrative segregation.

SEXUAL ASSAULT AND PRISON RAPE ELIMINATION ACT (PREA) INVESTIGATIONS

Traumatic experiences, such as sexual assault, can also impact the mental health of people incarcerated in the general prison population. A 2008 study by the Bureau of Justice Statistics ranked the ten U.S. prisons with the highest inmate-reported sexual assault complaints; five of those prisons were located in Texas. The Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA), a federal law passed in 2003, seeks to address this problem by instituting a zero-tolerance policy for prison rape in correctional settings. Though former Governor Rick Perry refused to comply with PREA standards, his successor, Governor Greg Abbott, stated in 2015 that Texas would comply with the federal standards “wherever feasible.”

The Texas PREA Ombudsman is responsible for ensuring that TDCJ is in compliance with federal regulations created to eliminate sexual assaults in prison facilities. In 2014, the PREA Ombudsman Office reviewed 727 administrative investigations of inmate-on-inmate sexual abuse allegations in Texas. About 40% of the incidents met the elements of the Texas Penal Code for Sexual Assault or Aggravated Sexual Assault. The PREA Ombudsman Office also received 766 allegations of staff-on-inmate sexual abuse and harassment. About 13% of these incidents met the elements of the Texas Penal Code for Sexual Assault or Aggravated Sexual Assault.

Behavioral Health Services and Programs in the State Criminal Justice System

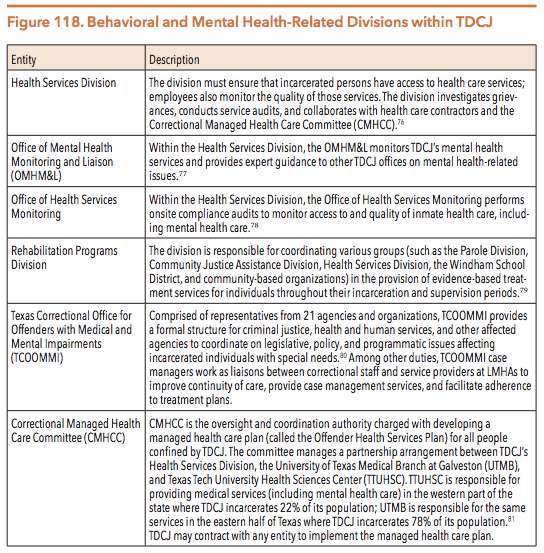

TDCJ is comprised of many subdivisions that manage and operate the agency, supervise incarcerated individuals, and provide services to crime victims. Within TDCJ, there are several offices and agencies that hold the responsibility for meeting the physical and behavioral health needs of inmates. Figure 118 provides a brief description of each office or agency.

In Estelle v. Gamble (1976), the U.S. Supreme Court determined that prison officials are constitutionally required to provide incarcerated individuals with appropriate health care services and that denial of such services constitutes cruel and unusual punishment. As the number of people with mental illness in state prisons rises, however, maintaining a constitutional level of care becomes challenging. Research over the past decade estimates that 50% of men and 75% of women in prisons across the U.S. experience a mental health problem that requires behavioral or mental health services each year.

To meet an individual’s behavioral health needs, TDCJ operates a managed health care plan rather than a fee-for-service plan. The average daily cost for people who requires medical care in Texas prisons is between $96 and $104 per person. The average daily cost in a psychiatric correctional facility is $145 per person.

Access to Services

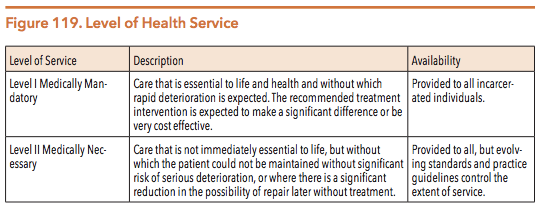

The Offender Health Services Plan developed by the Correctional Managed Health Care Committee (CMHCC) describes the levels of health care services made available to incarcerated individuals within TDCJ. The plan specifies two classifications of health services for medical, dental, and mental health needs. The classifications are listed in Figure 119 below.

Source: Correctional Managed Health Care Committee. (2015, September). Offender Health Services Plan. 4.

Additionally, each TDCJ facility must develop a process by which individuals who are incarcerated can gain access to medical, mental health, substance use, and dental care. At intake, incarcerated persons are provided information on how to obtain health care services within their assigned facility. Facilities may identify people with mental illness during the intake process or upon referrals from security staff who receive mental health-related training.

Behavioral Health Services

Qualified mental health providers may recommend the following mental health diagnostic and treatment services for incarcerated individuals with behavioral health needs:

- Emergency mental health services (available 24 hours a day, seven days per week);

- Professional services, such as medication management and monitoring;

- Continuity of care services;

- Psychosocial services;

- Crisis management/suicide prevention;

- Inpatient services provided by a correctional health care approved facility, including diagnostic evaluations, acute care, transitional care, and extended care; and

- Professional services, such as medication monitoring and management.

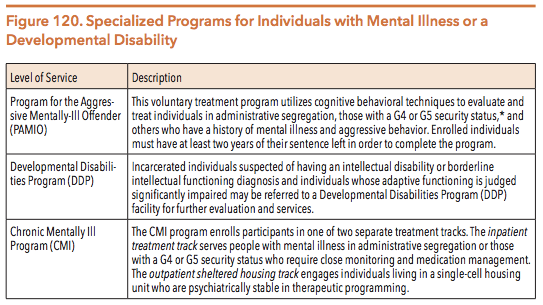

TDCJ also administers specialized programs for certain incarcerated individuals with a mental illness or developmental disability. Figure 120 describes these programs:

Source: Correctional Managed Health Care Committee. (n.d.). Correctional Managed Health Care Policy Manual. *Note: TDCJ classifies individuals housed in state prisons into six custody levels.89 Ranging from the least restrictive to the most restrictive, these levels include: G1 (General Population Level 1), G2, G3, G4, G5, and Administrative Segregation. Individuals with a G4 security status live in cells rather than dorms, and they may not work outside the security fence without armed supervision. Individuals with a G5 security status have histories of assaultive or aggressive behavior; they live in cells and may not work outside the security fence without armed supervision.

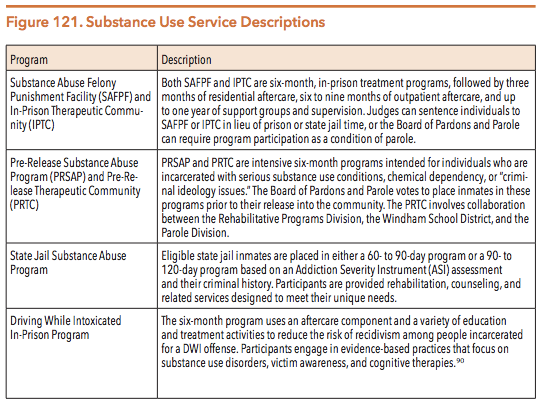

TDCJ also manages a number of programs within its Rehabilitation Programs Division to serve people with substance use conditions. Figure 121 below describes these programs.

Source: Texas Department of Criminal Justice. (n.d.). Rehabilitation Programs Division.

Post-Incarceration Community-Based Services

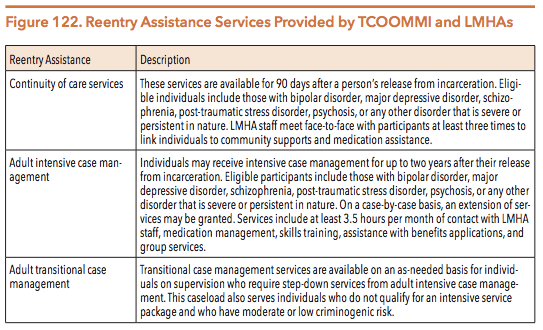

As part of TDCJ’s Reentry and Integration Division, the Texas Correctional Office for Offenders with Medical and Mental Impairments (TCOOMMI) provides a variety of institutional and community-based services to facilitate the reentry of incarcerated people with special needs into the community. Individuals with special needs include older adults and persons with physical disabilities, terminal illness, mental illness, and/or intellectual disabilities. TCOOMMI partners with local mental health authorities (LMHAs) to provide three tiers of reentry assistance for people with mental illness. Figure 122 describes each type of reentry support.

Source: Texas Criminal Justice Department. (2016, April). Personal communication: Reentry services.

Continuity of care programs are designed to include pre-release screenings of incarcerated clients and provide referrals for aftercare psychiatric treatment services, which are typically delivered by LMHAs. Upon release from incarceration, people with mental illness are referred to LMHAs for services, such as case management, psychological and psychiatric services, medication and monitoring, and benefit eligibility services (including federal entitlement application processing).

TCOOMMI’s transitional supports can be instrumental in reducing recidivism. Linking formerly incarcerated individuals to community services can help to address the root causes underlying a person’s previous criminal behavior in order to prevent reentry into the criminal justice system. In 2013, TCOOMMI implemented the Risk Needs Responsivity model to reduce recidivism among high-risk individuals utilizing TCOOMMI case management services. In 2015, the three-year recidivism rate was 12.4% for clients with high criminogenic risk and high clinical needs who were served for at least one year in TCOOMMI case management programs, while TDCJ’s general recidivism rate was 21.4%.

The majority of TCOOMMI’s services were traditionally reserved for individuals with one of three specific mental health diagnoses – bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, or schizophrenia. However, even among this narrow target population, only 25% of eligible individuals under parole or community supervision received TCOOMMI case management services in 2013. The remaining 75% of individuals with one of these diagnoses did not receive case management services due to a combination of their failure to meeting TCOOMMI’s criminogenic risk criteria and the agency’s lack of sufficient resources. During the 84th legislative session, lawmakers passed HB 1908 (84th, Naishtat/Garcia) to revise TCOOMMI’s eligibility requirements. Now, individuals with mental illness who have diagnoses other than bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, or schizophrenia may participate in TCOOMMI’s continuity of care and case management programs. The 84th Legislature increased TCOOMMI’s general revenue funding by $6 million for the 2016-2017 biennium to accommodate the change.

MEDICALLY RECOMMENDED INTENSIVE SUPERVISION

Medically Recommended Intensive Supervision (MRIS) is an early parole and release program that serves incarcerated people with special needs, including older adults and persons with mental and developmental disabilities, terminal illnesses, illnesses requiring long-term care, or physical disabilities. The purpose of the program is to release incarcerated individuals who pose minimal public safety risk back into the community in order to improve individual health outcomes and cut costs. If an individual is approved for early MRIS release, TCOOMMI specialists will expedite the release planning process and facilitate reentry case management. In 2015, 1,690 people incarcerated in state correctional institutions were referred for MRIS release, 210 were presented to the Board of Pardons and Paroles (BPP), and 82 were approved for release. That same year, 48 people incarcerated in state jails were also referred for MRIS release, 3 were presented to the presiding judge, and 3 were approved for release.

Discrepancies between the number of incarcerated persons who are referred for MRIS and the number of people who are ultimately approved for early release exist as a result of the MRIS referral process. Diverse sources, including unit medical staff, legislators, attorneys, TCOOMMI personnel, families of incarcerated persons, and incarcerated persons themselves, may initiate an MRIS referral. After a referral is made, a person’s eligibility must be determined based upon his/her current offense and medical condition. TDCJ representatives described that the vast majority of those who are referred for early release do not meet the program’s strict eligibility criteria and thus cannot have their cases presented to the BPP for a vote. For example, individuals who commit a sex offense must be in a persistent vegetative state or suffer from an organic brain syndrome that causes significant to total mobility impairment in order to qualify, while persons convicted of aggravated offenses must be terminally ill or require long-term care to qualify.

RELEASE ON PAROLE SPECIAL PROGRAMS

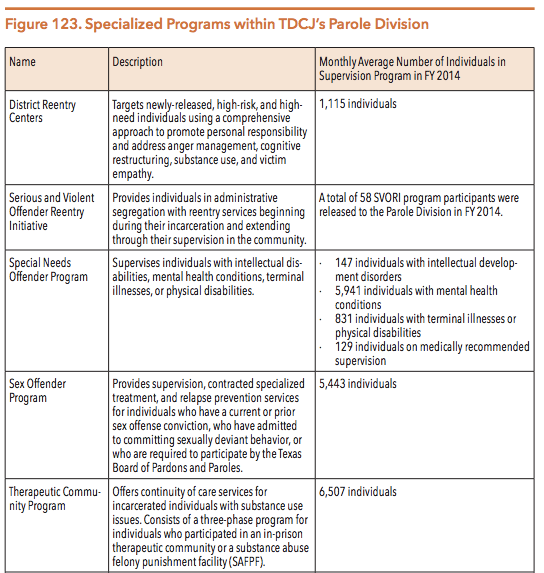

TDCJ’s Parole Division operates a series of specialized programs for individuals with mental health and behavioral health issues who are released from incarceration. Figure 123 below provides an overview of these programs:

Source: Texas Department of Criminal Justice. (2015). Annual Review 2014. 28-29.

Special Concerns for Incarcerated Females

If Texas were its own country, its rate of female incarceration would be the sixth highest in the world. Incarcerated women have distinct and possibly greater mental health needs than other people both inside and outside of correctional facilities. Incarcerated women are:

- Ten times more likely to be dependent on drugs than women without experience in the justice system;

- Seven times more likely to experience sexual abuse prior to their imprisonment than incarcerated males; and

- Four times more likely to experience physical abuse prior to their imprisonment than incarcerated males.

Research shows that women with histories of trauma and abuse require more specialized treatment than traditional, male-oriented models of care typically offer. TDCJ has a number of programs designed to accommodate for the special needs of its female population. For example, in 2010, TDCJ started the Baby and Mother Bonding Initiative (BAMBI) to address the physical, emotional, and health needs of women experiencing pregnancy or giving birth while incarcerated. Housed at the Santa Maria Hostel Unit, BAMBI seeks to combat recidivism by teaching new mothers the basics of parenting. Eligible participants typically include women scheduled for release within 12 months following their due date. Women who have been convicted of arson, a violent offense, a sex offense, or an offense against a child that caused harm or bodily injury cannot participate in BAMBI. In its first five years of operation, the program produced an 8% recidivism rate, and as of May 2016, 197 women have been enrolled in the program. TDCJ estimates that about 250 babies are born to incarcerated women in Texas each year, but the program can only serve 20 women at a time.

Local Criminal Justice Systems

Local criminal justice systems consist of law enforcement agencies, prosecutors, jails, courts, and probation departments that are responsible for promoting public safety by enforcing federal, state, and local laws in a specified region. Local systems are responsible for criminal cases from the point of arrest through the trial and sentencing stages. Local jails hold four groups of individuals:

- People who have not been convicted of a crime and are awaiting trial;

- People convicted of low-level offenses who are sentenced for short durations;

- People convicted of an offense who are awaiting transport to state facilities; and

- People found incompetent to stand trial who are awaiting a placement for competency restoration.

On June 1, 2016, Texas county jails operated at 70.5% of their collective capacity with a total jail population of 65,793. This population figure, however, masks the total number of people who cycle through jails each year. A daily population statistic (like the one provided above) gives a snapshot of the number of people detained in jail on a specific day. A statistic that shows the total number of people who spend time in jail, even if only for a few hours, during one year more clearly captures the high volume of people who experience confinement in a jail over time. In 2016, researchers estimated that people go to jail over 11 million times in the U.S. every year, though only about 646,000 people are jailed on any given day. In FY 2015, about one million people cycled through Texas jails.

Jail administrators face challenges in delivering services to their large detainee populations. In 2015, 50% of grievances submitted by incarcerated people to the Texas Commission on Jail Standards (TCJS) involved complaints regarding medical services, including mental health services. Leaders from the Texas Jail Project, a nonprofit that aims to improve jail conditions, reported that about 80% of the complaints they receive from inmates and their families typically involve a lack of adequate medical care.

Many people detained in local jails live with co-occurring mental health and substance use issues. Their untreated needs can lead to behavior that results in their entrance (or re-entrance) into the criminal justice system. Though jails are legally mandated to provide health services to detainees, the quality and availability of mental health services can vary widely between facilities. Large urban jails tend to provide treatment and successfully link individuals to community-based social services in order to prevent recidivism. Texans detained in other facilities, particularly those in rural areas with fewer resources, may experience deterioration of their mental health status due to a lack of adequate therapeutic services.

Despite the high proportion of people with mental health needs in jails, correctional officials often lack the training required to provide individuals with the mental health treatment and support that they need. County jail systems, especially in rural areas, may lack the necessary resources to implement best training and treatment practices in order to meet the needs of detainees with mental health conditions. For example, TCJS standards dictating the provision of medications to individuals upon their release from county jails do not exist. As a result, people with mental illness in affluent counties may receive over a week’s worth of medications upon their release, while those in less affluent counties may not receive any medications at all. Untreated mental health needs and a lack of post-incarceration treatment planning can lead to an individual’s cycling in and out of jail, which diminishes mental health outcomes and creates added policing and incarceration costs for local communities.

Texas Commission on Jail Standards

The Texas Commission on Jail Standards (TCJS) is an external regulatory agency for all county jails and seven privately-operated municipal jails. TCJS establishes minimum standards for the management and operation of Texas jails. TCJS’s key responsibilities include:

- Performing on-site inspections of jails to verify compliance with minimum standards;

- Providing technical assistance and training regarding jail management;

- Reviewing proposed jail construction and renovation plans;

- Auditing and reporting on jail populations;

- Providing management consultation; and

- Performing other activities relating to policy development and enforcement.

Out of the 254 counties in Texas, all but 19 operate at least one jail; therefore, TCJS must travel to 235 counties in addition to seven privately-operated facilities. Each county is visited for a compliance inspection at least once each fiscal year. TCJS does not perform oversight in municipal jails located in Texas.

TCJS standards include requirements for the custody, care, and treatment of jail detainees. Upon admission to jail, each individual receives a “health tag” that notes a special medical or mental health need in the individual’s medical record. Those needs are then brought to the attention of health personnel and/or the admissions supervisor on duty. Each facility must also create and implement a written health services plan for the jail population’s medical, mental health, dental, and pregnant inmate services and maintain a separate health record for each incarcerated person. These health records must include a health screening and a mental health evaluation administered by medical personnel or by a trained booking officer upon a person’s entry into the jail. At a minimum, each record should also contain current medical and mental health treatment information and behavioral observations, including the incarcerated individual’s state of consciousness, risk of suicide, and mental health status.

Correctional administrators may use inmate health records when individuals are transferred to or re-incarcerated within different facilities across the state. TCJS does not formally require jail administrators to share incarcerated persons’ health records with other entities, but many do obtain these records with a signed release. However, TCJS does require jail administrators to send a Texas Uniform Health Status Update form when incarcerated persons are transferred from one jail to any other correctional facility. Furthermore, the Texas Health and Safety Code requires various agencies, including local jails, TCJS, and TDCJ, to disclose and accept information relating to incarcerated persons with mental illness, disabilities, and/or other special needs in order to improve continuity of care services “regardless of whether other state law makes that information confidential.” This information may include details about an incarcerated person’s treatment needs; social, criminal, and vocational history; supervision status; and medical and mental health history.

Suicide in Local Jails

National data show that suicide occurs roughly three times more frequently in jails than in prisons. People with mental illness who are awaiting trial (and thus have not been convicted of a crime) are at even greater risk. National data show that pretrial individuals complete suicide at a rate seven times higher than their convicted peers do.

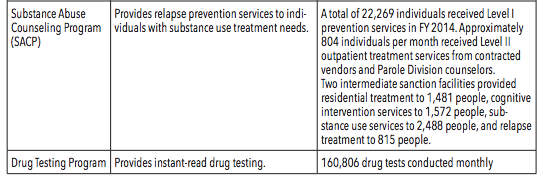

In Texas, the number of jail suicides increased by about 43% between CY 2014 and CY 2015. Figure 124 demonstrates the number of suicides that occurred within county jails between 2011 and 2015.

Source: Texas Commission on Jail Standards. (2016, May 18). Data request: Suicides in county jails

To decrease the incidence of suicide in jail settings, the Texas Administrative Code requires county sheriffs and jail operators to develop and implement a mental disabilities/suicide prevention plan. Jail officials are given flexibility in how they construct these plans, but at a minimum, each plan must address the following:

- Staff training procedures regarding the identification, supervision, and management of incarcerated individuals who have a mental disability and/or are potentially suicidal;

- Intake training procedures to identify persons who are suicidal;

- Communication and documentation procedures to relay and maintain information about suicidal individuals;

- Intervention and emergency treatment procedures prior to the occurrence of a suicide and during the process of a suicide attempt;

- Reporting procedures to inform outside authorities and family members about completed suicides; and

- Review mechanisms for jail administrators and medical and mental health staff following all attempted and completed suicides.

Jail administrators in Texas also use an approved screening tool to identify detainees who are at risk for suicide. Upon admission to the jail, each individual must be evaluated immediately with a TCJS-approved mental disabilities/suicide prevention screening instrument. The previous instrument asked newly incarcerated people to self-report their medical problems and mental health histories, but jail employees still had discretion when determining whether to refer the person to treatment services. The new form that was created in 2015 removes subjectivity from the process. Jail employees must now follow explicit instructions when detained individuals provide certain responses to predetermined questions. For example, the new screening form contains the question: “Are you feeling hopeless or have nothing to look forward to?” If the detained person answers “yes,” jailers must immediately notify a supervisor, magistrate, and mental health professional. The form also uses a grading system to provide further guidance on when jailers should contact a mental health professional if they suspect suicidal risk but the screening instrument fails to initiate an immediate referral.

In October 2015, the new form was tested in several counties across the state. Jail administrators in tested facilities reported increases in the number of individuals placed on suicide watch after the new procedure was put in place. On December 1, 2015, all Texas counties were required to implement the updated mental health screening form. In December 2016, TCJS will conduct an analysis to assess the new form’s impact on jail suicide rates.

Incarceration Prevention and Diversion Programs

Increased demand for mental health services within state prisons and county jails has pushed stakeholders to develop opportunities for diversion from incarceration. For example, local mental health authorities (LMHAs) provide community-based interventions to prevent criminal justice involvement. TCOOMMI also collaborates with all 39 LMHAs to provide multi-service alternatives to incarceration for justice-involved individuals with special needs (See page X in this chapter of the guide for more information on TCOOMMI.) Finally, TDCJ awards grant funding to county stakeholders in order to pursue the top goal outlined in its 2017-2021 strategic plan: “to provide diversions to traditional incarceration.” The aim of these prevention and diversion programs is to use cost-effective, safe, and clinically appropriate strategies that curb the over-incarceration of people with mental illness charged with low-level crimes.

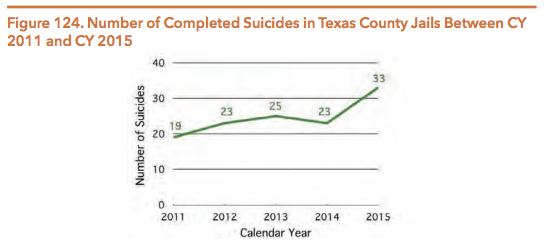

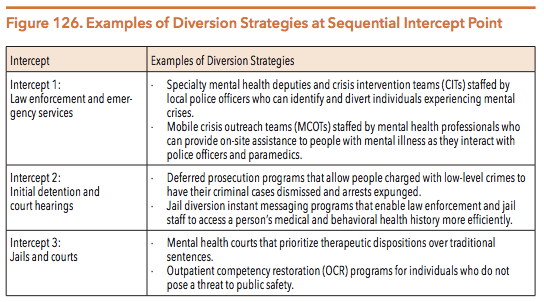

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) promotes the sequential intercept model as a way to organize prison and jail diversion strategies. The sequential intercept model, developed in conjunction with the GAINS Center, emphasizes five “intercept points” at which individuals may be diverted from the justice system. The intercept points illustrated in Figure 125 include:

- Intercept 1: Law enforcement and emergency services;

- Intercept 2: Initial detention and court hearings;

- Intercept 3: Jails and courts;

- Intercept 4: Reentry into the community; and

- Intercept 5: Community corrections and support services.

Source: H. Steadman. (2014, July). “When Political Will Is Not Enough: Jails, Communities, and Persons with Mental Health Disorders.” John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Criminal Justice Reform Initiative. 4.

Figure 126 below describes specific diversion strategies that can be implemented at each step of the sequential intercept model.

Source: Frost, L. (2016, January 22). Mental Health Diversion from Jail. University of Houston Law Center Police, Jails, and Vulnerable People Symposium.

COMMUNITY EXAMPLES OF JAIL DIVERSION STRATEGIES

At each step of the criminal justice process, the sequential intercept model encourages collaboration between LMHAs, law enforcement agencies, and the court system. Collaboration among key stakeholders helps to ensure that people with mental illness who commit minor offenses are linked to community-based, recovery-oriented treatment as soon as possible. Jail diversion efforts can then improve mental health outcomes, save money, and increase public safety.

Section 533.108 of the Texas Health and Safety Code permits LMHAs to prioritize funds for the creation of collaborative jail diversion programs with law enforcement, judicial systems, and local personnel. The type of programs available to persons with mental illness varies from county to county. Some communities, like Bexar and Harris counties (described below), offer robust diversion opportunities that address multiple intercepts of the sequential intercept model. Other rural and urban areas, however, do not have the resources to implement any type of diversion strategy at all. As a result, only a small fraction of Texans with mental illness who are eligible for diversion programming actually receive diversion services.

Bexar County Jail Diversion Program

In 2003, Bexar County implemented a jail diversion program that is now viewed as a national service model. Bexar’s diversion initiative was created by the Center for Health Care Services using diverse funding sources, including private donations; city, county, and state dollars; and federal block grants. The program employs both pre- and post-booking diversion methods. First, Bexar County uses a 24/7 crisis center to provide county residents with immediate intervention when they are experiencing a mental health crisis. Then, Mobile Crisis Outreach Teams (MCOTs) and Crisis Intervention Teams (CITs) work to divert individuals with mental illness away from jail settings before they are arrested and booked in a local jail. After booking, the diversion program identifies people with mental illness already in the system and recommends appropriate alternatives to jail, such as court-supervised community treatments or mental health bonds. Finally, Bexar County offers programs, such as Haven for Hope, that provide continuity of care and housing services for people in need of assistance who are released from incarceration into the community.

Since its implementation, Bexar County’s jail diversion strategies, combined with falling crime rates, significantly reduced the county jail population. In 2003, the jail population exceeded the jail’s capacity by nearly 1,000 people, but by February 2016, over 1,000 beds were empty at the Bexar County Jail. Since 2003, program administrators estimate that about 20,000 people have been diverted from jail to treatment, which saves the county approximately $10 million per year. Mental health-related training also helped to decrease the use of physical force by Bexar County law enforcement officers against people with mental illness. In 2009, officers used physical force about 50 times per year when taking a person with mental illness into custody; between 2009 and 2015, officers used similar force only three times total.

Harris County Jail Diversion Pilot Program

In recent years, Harris County, home to the third largest jail in the nation, has adopted diversion strategies similar to Bexar County’s program. In 2013, state legislators passed SB 1185 (83rd, Huffman/Schwertner) to create a mental health jail diversion pilot in Harris County. The ongoing goal of the program is to promote and sustain recovery for justice-involved individuals with mental illness by expanding services in the areas of housing, education, supportive employment, and peer advocacy. Between 2014 and 2017, the state and county both appropriated $5 million each year to support the pilot.

The Harris County pilot program uses two local providers to safely divert people with mental illness away from the criminal justice system. First, the Harris Center for Mental Health and IDD (formerly MHMR of Houston) uses a jail-based team, a community- and clinic-based team, and critical time intervention (CTI) services; together, these strategies identify incarcerated people with mental illness, initiate prerelease treatments, and link participants to established community support networks. Second, Healthcare for the Homeless-Houston and SEARCH Homeless Services enroll eligible participants in a Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) program (for more on PSH, see the TDHCA chapter of this guide). At each stage of the program, people with mental illness receive evidence-based services, including cognitive behavioral therapy, substance use interventions, peer support, and intensive case management.

Between August 2014 and April 2016, the pilot program served 1,107 people, which includes persons who were screened, assessed, and enrolled. The cost per participant was $5,401.53. DSHS is required to submit a formal program evaluation to legislators by December 1, 2016.

SPECIALTY COURTS

Counties can also use specialty courts to divert people with serious mental illness and substance use conditions away from jail settings. These courts apply problem-solving techniques to provide community-based alternatives to incarceration. Each type of specialty court requires the collaboration of judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys, law enforcement officers, and mental health professionals. The most common types of specialty courts relevant to criminal law, mental health, and substance use are drug courts, mental health courts, family drug courts, DWI courts, and veterans’ courts.

In July 2016, there were 191 specialty courts operating in Texas. In FY 2016, the Criminal Justice Division (CJD) of the Office of the Governor allocated $11.6 million in general revenue-dedicated funds for discretionary grants to 89 specialty courts across Texas. In FY 2015, CJD-funded courts served approximately 3,570 participants, 61% of whom completed their program successfully.

In 2013, the Criminal Justice Division of the Office of the Governor produced an overview of Texas specialty courts, which stated that these courts have reduced the number of people with mental illness who are incarcerated in the state. However, the Hogg Foundation’s attempts to gather data on the total number of individuals who are served within these resource-intensive programs compared to those who could potentially benefit from such services demonstrate the need for improved data collection and analysis among existing specialty court programs. As of July 2016, centralized data on the number of individuals served in all specialty courts (not only those funded through CJD grants) and their overall outcomes did not exist. Further, although research shows that the courts produce positive outcomes, recent data also highlight racial and ethnic disparities in access to some specialty courts, particularly drug courts and mental health courts.

Drug Courts

Drug courts provide supervision that is more comprehensive and intensive than other forms of community supervision. The drug court model assumes that supervised treatment in combination with judicial monitoring can more effectively reduce drug use and crime than either treatment or judicial sanctions can achieve separately. Data show that this model works; researchers have found that drug court participation can decrease three-year recidivism rates by up to 50%. In 2001, the 77th Legislature passed HB 1287 (77th, Thompson/Whitmire), which mandated all Texas counties with populations exceeding 550,000 to apply for federal and other funds in order to establish drug courts. In February 2016, there were approximately 80 drug courts (not including DWI courts) in counties throughout Texas.

Mental Health Courts

Mental health courts were developed across the country as an alternative to the standard adjudication process for people with mental illness who have committed low-level offenses. Like drug courts, mental health courts use non-adversarial, judicially-supervised treatment plans to reduce recidivism that is fueled by untreated mental illness and substance use conditions. The two types of courts differ, however, because drug courts are more likely than mental health courts to use a formalized set of treatment steps and to employ punitive sanctions for treatment noncompliance.

In 2012, Harris County implemented a felony mental health court using a grant from the Bureau of Justice Assistance. Components of the court program include:

- Comprehensive criminogenic risk assessments to determine the likelihood of future criminal behavior;

- Clinical psychosocial evaluations to determine each participant’s strengths and needs;

- Frequent appearances before the felony mental health court judge;

- Regular visits with specially trained community supervision officers;

- Intensive treatment by mental health professionals;

- Substance use treatment for participants with co-occurring mental health and substance use conditions; and

- Random alcohol and drug testing

The court team is comprised of a diverse group of professionals, including: two district court judges, a project director, three full-time licensed mental health clinicians, two dedicated part-time assistant district attorneys, two dedicated part-time assistant public defenders, three dedicated full-time community supervision officers, a clerk, and a bailiff. The court’s typical caseload is about 55 to 60 cases. Once participants are accepted into the program, they must work with the court team for a minimum of 18 months. The court team then holds two graduation ceremonies each year in which past, current, and potential graduates may participate.

In order to promote graduation from the program, staff members connect clients to community-based services that reflect the participant’s unique needs and strengths. If the client fails to meet the program’s requirements, staff members first attempt to identify barriers to success, but if that is unsuccessful, staff can use graduated sanctions to address the client’s behavior. The court’s clinical team also works with participants to develop an individualized reentry plan that focuses on five main areas of interest: mental health treatment, medication management, housing needs, substance use treatment, and access to income and benefits.

Because of court team’s services are so intensive and time-consuming, Harris County’s mental health court can only serve a small fraction of defendants with mental illness. As of March 1, 2016, the court had served 130 participants, 75.4% of whom had co-occurring mental health and substance use conditions. By February 2016, 39 participants had successfully graduated from the program and another six participants were on track to graduate by the spring of 2016.

MENTAL HEALTH PUBLIC DEFENDER OFFICES

Criminal cases involving people with mental health conditions often present unique legal issues that require specialized knowledge and skills. Jurisdictions that have a public defender office can train attorneys on mental health-related issues in order to better serve clients with mental illness. Not all counties, however, have such an office in place. Thus, some areas without designated countywide public defenders have established a Mental Health Public Defender (MHPD) Office that specializes in addressing the legal needs of people with mental illness who are charged with crimes.

In 2007, Travis County, which does not have a public defender office, received a four-year grant to begin the nation’s first stand-alone MHPD Office. Administrators set four major goals for the office:

- Minimize the number of days that people with mental illness spend in jail;

- Increase the number of case dismissals among defendants with mental illness;

- Reduce recidivism by providing intensive case management services; and

- Enhance legal representation by providing attorneys with the specialized knowledge they need to defend persons with mental illness.

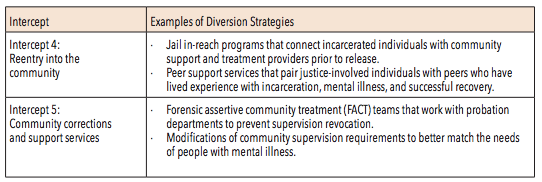

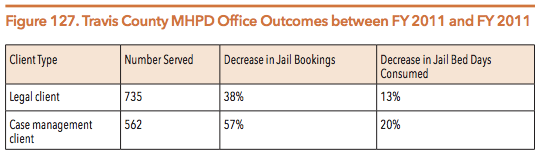

A 2011 cost benefit analysis of the Travis County MHPD found that 41.2% of misdemeanor clients remained out of custody and/or had not returned to jail for up to five years after receiving MHPD Office services. Figure 127 shows the percent by which the MHPD Office also decreased jail bookings and jail bed days consumed among different types of clients. In the spring of 2016, the Travis County MHPD Office also began conducting a second cost benefit analysis.

Source: Travis County Attorney’s Office. (2011). Mental Health Public Defender Office Cost Benefit Analysis, Part 1: Analysis of Performance of the Texas Task Force on Indigent Defense Grant. 2-3.

As of March 2016, there were four MHPD Offices in Texas located in Bexar, El Paso, Fort Bend, and Travis counties. These counties all have a MHPD representing defendants charged with misdemeanors. The Travis and Fort Bend MHPD Offices also provide referrals to a variety of social services for defendants charged with felonies.

REENTRY PEER SUPPORT

Successful reintegration into the community can be a challenge for formerly incarcerated people with a criminal record. Peer support has become an established service in other contexts (e.g., reentry from state hospitalization), and interest is growing for the use of peer support in incarceration settings. Reentry peer support programs allow people with lived mental health and criminal justice experience to mentor others in the justice system who are beginning the recovery and reentry process. Peers are able to share strategies, coping skills, and experiences with the state mental health system to help participants successfully navigate the difficult transition back into the community (for more information in peer support services, see the Texas Environment chapter of this guide).

In 2015, legislators approved Rider 73 to the DSHS budget, which created a peer support reentry pilot program in Texas. In April 2016, DSHS began funding pilot programs in three locations: Harris County, Tarrant County, and Tropical Texas (which serves Cameron, Hidalgo, and Willacy counties). County sheriffs and LMHAs in each location will use certified peer support specialists to help individuals with mental illness successfully transition out of local jails and into their communities. The non-profit Via Hope created a reentry endorsement training (i.e., a specialization) to prepare peer specialists for their work with justice-involved individuals living with mental illness. Via Hope then developed the curriculum for the pilot’s peer support specialists and began training peer specialists in advanced reentry skills and service provision at the end of March 2016. As of July 2016, 26 individuals completed the reentry peer training program, and all three pilot locations had hired a reentry peer specialist to implement the program. The Hogg Foundation for Mental Health will oversee the program’s evaluation and release formal results in December 2016 and September 2017.

NEXT SECTION: TEXAS JUVENILE JUSTICE DEPARTMENT AND LOCAL JUVENILE JUSTICE AGENCIES

DOWNLOAD A PDF OF THE FULL GUIDE