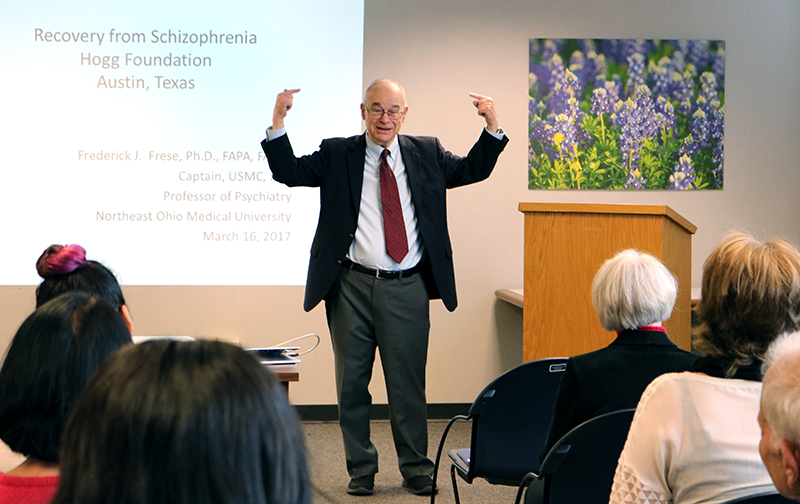

When Dr. Fred Frese speaks, you listen.

That was just one of many lessons learned last week at the Hogg Foundation’s biannual public forum on mental health, where Dr. Frese delivered a rousing, deeply informative presentation on mental illness and the potential for recovery.

At 25 years old, Dr. Frese was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. Ten years would pass before he came to identify as a “consumer” (a person with lived experience of mental illness), during which time he endured just as many institutionalizations.

Since then, he has gone on to earn a doctorate in psychology, serve as Director of Psychology at Western Reserve Psychiatric Hospital, and lead a prolific career in higher education and public speaking.

Dr. Frese has also become a fierce defender of recovery-oriented research and policy. At the forum, he took the time to not only share insights from his own experience, but also connected his experience to the broader history and current activity of the recovery movement.

Recovery in Private Life and the Public Eye

Recovery, as defined by SAMHSA, is a “process of change through which individuals improve their health and wellness, live a self-directed life, and strive to reach their full potential.”

For Dr. Frese, the “turnaround” that initiated his recovery happened at a Veteran’s Affairs hospital in Ohio, where a previous facility had transferred him after uncovering his military service record. Prior to joining the military, he had also earned a B.A. in Psychology – an education that came in handy whenever the hospital asked him to complete various psychological tests.

One psychiatrist was particularly impressed with Dr. Frese’s results. “If it weren’t for you having this schizophrenia,” the psychiatrist told him, “you might even have become a professional.”

The offhand remark stuck with Dr. Frese, who decided to take the psychiatrist up on his challenge. After being deinstitutionalized, he briefly worked as a prison psychologist before enrolling in a full-time master’s program in psychology at Ohio University.

Release, however, is not the same as recovery. Dr. Frese said he owed his resistance to delusions – what he called the “cardinal symptom” of schizophrenia – to a “convolution of things happening.” One was the discovery of a confidante and life partner: his wife.

“It really helps to have somebody you can trust – who can give you feedback,” Dr. Frese said. “Now in my case it’s a wife, but it doesn’t have to be a wife – it can be a friend, or a therapist, or somebody.”

Finding equally secure footing in public life proved more difficult. Dr. Frese’s ability to advance his academic pursuits hinged on the absence of discriminatory filters on school applications. Workforce reentry, on the other hand, wasn’t so forgiving a process.

“The worst part about having schizophrenia in my life, without a doubt: no jobs,” Dr. Frese said. “Nobody will hire me. A hundred different interviews, and every one of them will say, ‘Oh, mentally ill – we don’t hire you people.’ That’s tough.”

The Recovery Movement

Discriminatory hiring practices are hardly a thing of the past. Advocates like Dr. Frese – along with other practitioners willing to “come out” as consumers – have put decades of work into reforming the pejorative discourse and practices that perpetuate misconceptions of mental illness.

From the Psychiatric Inmates’ Liberation Movement of the second half of the twentieth century to the creation of NAMI in the late 1970s to the enactment of the 21st Century Cures Act this past year, consumer-driven pushes for recovery-oriented services and supports continue to gain momentum and show promise.

The parameters of the AbilityOne program, which has incentivized the employment of people with disabilities since the 1930s, have also expanded to include individuals living with mental illness. Still, Dr. Frese cautions against complacence.

The consequences of malformed mental health practices and even miscalculated activism, he said, live on in the prison-industrial complex and homeless epidemic. Insufficient means of promoting and distributing recovery resources also obstruct those in need from obtaining assistance.

If marginalized consumers are to be reached, such a fragmented system simply will not do. “Something has to be done,” Dr. Frese emphasized.

Dr. Frese praised the Hogg Foundation’s Recovery to Practice grant program for continuing this fight on the state level. As for him, he will continue speaking out and educating audiences about recovery – a true gift for all who have the opportunity to listen.

RELATED CONTENT

WATCH: Frede Frese Lecture

On March 16, 2017, Dr. Frese delivered a rousing, deeply informative presentation on mental illness and the potential for recovery. We captured his presentation in a four-part video series.